Biological Sciences

Tissue Fluid

Tissue fluid, also known as interstitial fluid, is the fluid that surrounds the cells in the body. It is derived from blood plasma and contains water, nutrients, gases, and other substances that are exchanged with the cells. Tissue fluid plays a crucial role in delivering essential substances to cells and removing waste products from them.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

7 Key excerpts on "Tissue Fluid"

- eBook - ePub

- Salvatore V. Pizzo, Roger L. Lundblad, Monte S. Willis(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

19 But this space and its fluid content also play a role in disease. The interstitial space is a dynamic environment where an interplay of proteases, polysaccharides, cytokines, and inflammatory cells dictates the pathophysiological responses to tissue injury. In the subsequent chapters, we will consider the various compartments of this fluid, their components, and their regulation.TABLE 1.1Protein Content of Various Human Body Fluids and SecretionsFluid Protein (mg/mL)aComment Refs. Extracellular fluid N/A The body fluid can be divided into two major components: the intracellular fluid and the extracellular fluid. Between 60% and 70% of the body fluid is intracellular in nature, while the remainder is extracellular in nature. The extracellular fluid, in turn, consists of two primary components: intravascular fluid (blood plasma; approximately 25%) and extravascular fluid (approximately 75%). The extravascular fluid consists mostly of interstitial fluid with small specialized fluids in various spaces; specialized fluids include cerebrospinal fluid, synovial fluid, and ocular fluid.1 –5Blood plasma 78.9 ± 0.5bA protein-rich fluid defined by being confined within the vascular system and representing one-quarter to one-fifth of the total extracellular fluid. It is in equilibrium with the interstitial fluid, which feeds into the lymphatic system and is returned to the venous system. Other areas of extracellular fluid include the peritoneal fluid, ocular fluid, and cerebrospinal fluid. Plasma is also defined as the protein-rich fluid obtained by the removal of the cellular elements of whole blood collected with an anticoagulant. - eBook - PDF

- David Ucko(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

A large fraction of the total extracellular liq-uid is taken up by the interstitial fluid, which contributes about 1 5 % of the b o d y weight. It lies in the spaces b e t w e e n the cells; most o f it cannot flow freely, but rather hydrates the molecules in the interstitial spaces. A large part is present in a gel c o m p o s e d mainly of hyaluronic acid, a polysaccharide that acts as a cement holding cells together. Dissolved substances can diffuse through this gel on their way b e t w e e n b l o o d and tissue cells. Although the terms interstitial fluid and l y m p h are sometimes used to a ter e str t e d u ds mean the same thing, lymph is more correctly defined as the fluid in the lym-phatic ducts. These are part of a special circulatory system that includes lymph veins and capillaries but no arteries, as shown in Figure 22-7. T h e lym-phatic system serves to return materials from the tissue to the blood, particu-larly protein and excess Tissue Fluid. This process is important for maintaining the normal osmotic balance b e t w e e n the b l o o d and tissues. W h e n it is not functioning properly, edema, an excessive accumulation of fluid in the tissue spaces, develops. Another important property of the lymph is its ability to ab-sorb fats from the intestine. In addition, the lymph nodes, masses of connec-tive tissue present in the lymphatic system, form certain types of white b l o o d cells and act as filters, trapping dead cells and destroying bacteria. Important extracellular fluids are produced by secretion, that is, formation or separation from the b l o o d or interstitial fluid by an energy-requiring process. Examples are the aqueous humor of the eye and the cerebrospinal fluid, which surrounds the brain and spinal cord. Tears are a secretion that keeps the surface of the cornea wet, protecting the eye and improving its o p -tical properties. - eBook - PDF

Cells and Tissues

An Introduction to Histology and Cell Biology

- Rogers(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

5.1 The movement of fluid across the wall of a capillary. H = hydrostatic pressure: 0 = osmotic pressure. 66 Cells and Tissues Fig. 5.2 A spread of con-nective tissue from the mesen-tary of the rat. Orcein and light green. (X 400.) By this mechanism, the extracellular fluid of connective tissue is constantly renewed. Nutrients and dissolved oxygen diffuse into the Tissue Fluid and waste products, including carbon dioxide, are removed: large local variations in composition of the Tissue Fluid are prevented. Removal of proteins from the extracellular fluid Note the important part played by the plasma proteins in the renewal of the extracellular fluid: the return of fluid to the venous end of the capillary depends in part on the osmotic effect they exert. If proteins accumulate in the extracellular fluid, they cannot pass the capillary wall into the blood, and their osmotic effect opposes that of the plasma proteins, leading to retention of water in the extracellular spaces. Yet proteins appear in the extracellular fluid, since some plasma proteins escape from the capillaries and cells inevitably die, liberating debris, while the extracellular structures produced by them also break down. The body has two mechanisms to prevent the gradual accumulation of proteins in the extracellular fluid — one cellular, the other an alternative route back into the blood stream. The cellular mechanism consists of the activity of macrophages, which take debris of all sorts into phagocytic vacuoles inside their cytoplasm. Digestion of debris and soluble proteins then takes place within the cell. The second mechanism involves the provision of a second set of capillaries, of basically similar construction to those that contain blood, but of wider diameter: the terminal lymphatic capillaries are blind sacs lined with endothelial cells that overlap each other. Unlike the endothelial cells of blood capillaries, they are not joined to each other by tight junctions. - eBook - PDF

- Joseph D. Bronzino, Donald R. Peterson(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

22 -1 22.1 Introduction The transport of fluid and metabolites from the blood to the tissue is critically important for maintain-ing the viability and function of cells within tissues Similarly, the transport of fluid, biological signaling molecules, microorganisms, and cell disposal products from the tissue to the lymphatic system of vessels and nodes is also crucial to maintain immune surveillance and tissue and organ health Therefore, it is important to understand the mechanisms for transporting fluid containing micro- and macromolecules or colloidal materials from the blood to the tissue and the drainage of this fluid into the lymphatic sys-tem Because of the abbreviated nature of this chapter, readers are encouraged to consult more complete reviews of blood/tissue/lymphatic transport by Kawai and Ohhashi (2009), Aukland and Reed (1993), Hargens and Akeson (1986), Jain (1987), Lai-Fook (1986), Schmid-Schönbein (1990), Schmid-Schönbein and Zweifach (1994), Staub (1988), Staub et al (1987), Wei et al (2003), and Zweifach and Silverberg (1985) and on lymphangiogenesis and its biological and biophysical control factors (Adams and Alitalo, 2007; Swartz and Fleury, 2007; Tammela and Alitalo, 2010) Muthuchamy and Zawieja (2008) have sum-marized the contractile protein machinery of the lymphatic smooth muscle Many previous studies of blood/tissue/lymphatic transport have used isolated organs or whole ani-mals under general anesthesia Under these conditions, the transport of fluid and metabolites is arti-ficially low in comparison to animals that are actively moving In some cases, investigators employed passive motion by connecting an animal’s limb to a motor to facilitate studies of blood to lymph trans-port and lymphatic flow However, new methods and technology allow studies of physiologically active animals so that a better understanding of the importance of transport - eBook - PDF

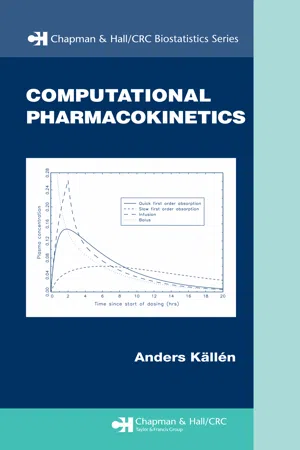

- Anders Kallen(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Chapman and Hall/CRC(Publisher)

To find the intracellular space we need to find the total volume of body water, which can be done with heavy water, and then subtract the ECF volume. Intracellular water is contained within the cell by the cell membrane, which is built up of a double phospholipid layer with large molecules like proteins embedded in it. Some of these are receptors that may be the target of our drug, something to be discussed in Chapter 6. The cell membrane is semi-63 64 Computational Pharmacokinetics permeable in that it allows easy passage of some molecules but not of others, depending on molecular size and its physio-chemical properties. Lipophilic substances, like oxygen and CO 2 , pass easily through the walls, whereas hy-drophilic substances, including water, need to find pores in the cell membrane to pass through, and therefore can only enter if they are small enough. This means that there is an osmotic pressure over the cell membrane. The term osmosis 1 refers to the motion over a semi-permeable membrane which makes, for instance, water move towards the side with the overall higher particle concentration. In general the different fluids in the body are separated by semi-permeable membranes. As a result the molecule composition of different aqueous spaces differ. An assembly of similarly specialized cells and their derivatives (intercellular substances) is called a tissue . Tissue classification, which refers to cell type, not function, includes epithelial tissues, which cover all external and inter-nal surfaces of the body, muscle tissue, comprising of all contractile elements, nerve tissue, and connective and supporting tissues (bones, cartilage). The latter are found in the locomotor apparatus, in blood vessels, and in sup-porting structures. Cells of these basic tissues are in different ways combined to form larger, functional units which we call organs. We will not distin-guish clearly between organ and tissue, instead we will use the two words interchangeably. - Neil Herring, David J. Paterson(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

the entire plasma volume completes an extravascular circulation in under one day , except for the plasma proteins. Consequently, the distribution of fluid between the plasma and interstitial compartment can be distorted relatively quickly by changes in capillary or lymphatic function. For example, increased capillary filtration during prolonged standing or exercise reduces the plasma volume by up to 20%, and increased capillary filtration during cardiac failure drives an excess of water in the tissues (oedema). To understand such fluid shifts, we must first identify the forces that determine fluid exchange.11.1 THE STARLING PRINCIPLE OF FLUID EXCHANGETranscapillary fluid movement is a process of plasma ultrafiltration across a semipermeable membrane . Water and electrolytes pass through the wall more easily than plasma proteins, producing an ultrafiltrate with a substantially reduced protein content - the interstitial fluid. The ultrafilter is the endocapillary coating of biopolymers, the glycoca-lyx (Figures 9.3 , 9.5 and 10.10 ). The glycocalyx interpolymer spaces function as a system of small pores (radius 4-5 nm), that are permeable to water and small solutes but are too narrow to transmit plasma proteins readily. The glycocalyx is thus a semipermeable membrane; it covers the entrance to the intercellular cleft, through which the plasma ultrafiltrate flows to reach the pericapillary, interstitial space (Figure 11.1 b). In fenestrated capillaries, the fenestrae provide an additional, subglycocalyx pathway permeable to water (Figures 10.10 and 10.11 ). In discontinuous capillaries, the gaps further enhance permeability (Figure 10.2- eBook - PDF

Lymphatics and Lymph Circulation

Physiology and Pathology

- István Rusznyák, Mihály Földi, György Szabó, L. Youlten(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Pergamon(Publisher)

The ground substance, apparently homogenous if analysed optically, constitutes the second category of the intercellular substances of the connective tissue. Its most characteristic component is a glucoprotein, i.e. a protein whose molecules also contain carbohydrate. The composi-tion of the ground substance is, as suggested by Gersh and Catchpole, identical with that of the basement membrane which surrounds the vascular structures and the parenchyma cells, thus separating them from the connective tissue. Essentially, the basement membrane, is, according to the theory, a concentrated ground substance in which there are also reticular (argentophil) fibres constituting a profuse network. The relationship between the ground substance of the connective tissue and the interstitial fluid was another unsolved question until quite recent times. The assumption that there exist slits or clefts in the connective tissue which contain freely moving fluid has, as we have noted, been disproved by the investigations of Hülse (1918) and 372 Lymphatics and Lymph Circulation Hueck (1920). It is, according to Schade and Menschel (1923), almost impossible to squeeze a few droplets of fluid out of the subcutaneous connective tissue even with fairly high mechanical pressure. The tis-sue fluid is, therefore, not to be found free in either macroscopically or microscopically visible gaps. Nor is it bound to the intercellular col-loids as was claimed by Schade and his associates. The amount of water bound to colloids in mammals is practically negligible. As long ago as 1924, Anitschkow found that intravenously injected colloidal dye-stuff (trypan blue) escaped rapidly from the blood capil-laries and stained diffusely the entire interstitial connective tissue. Perivascular and perineural connective tissue which contains ground substance in a more concentrated form was found to respond to vital stains with a special intensity.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.