History

Anti-War Movement

The Anti-War Movement refers to a collective effort by individuals and groups to oppose and protest against war and military intervention. It has been a prominent feature of many historical periods, with activists advocating for peaceful resolutions to conflicts and criticizing government policies that lead to war. The movement often involves demonstrations, rallies, and other forms of public activism to raise awareness and promote peace.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Anti-War Movement"

- eBook - ePub

War

Contemporary Perspectives on Armed Conflicts around the World

- Cameron D. Lippard, Pavel Osinsky, Lon Strauss(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

tolerance, peace, and nonviolent civil disobedience to curtail conflict and bring about social equality and justice. Although research is scant on how effective these efforts have been, there is consensus that antiwar organizations and peace activists have chipped away at pro-war cultural ideologies. They have also pushed humanity to find ways to negotiate conflict without violence by finding ways to resolve differences and bring about social justice for the disenfranchised.However, antiwar movements are different from most antiwar organizations, peace movements, and other social movements that we have grown to understand (i.e., the American Civil Rights Movement or Feminist Movement). Daniel Lieberfeld’s (2008) article on antiwar movements defines and explains how antiwar movements are different. First, he suggests that an antiwar movement is an ad-hoc movement that attempts to change government policy regarding a specific and ongoing war. Thus, this movement usually addresses a specific policy or incident and looks for a negative peace solution. However, social justice movements often want their movement to create results more closely aligned with positive peace in which grievances and reconciliation are goals. Second, antiwar movements also claim that those who control the state have broken their social contract with its citizens to bear the burden of an unnecessary and harmful war (i.e., death through military participation). While this notion that the government is not holding up its part on the contracts of civil society in other movements, antiwar movements suggest that politicians and governments are not making rational decisions about armed conflict and are not considering the human and economic costs. Thus, it is a movement against the state and its use of the military. Lieberfeld (2008) argues that this stance can seem to many as unpatriotic in a country in which nationalism is strong and requires homeland security. Finally, and related to the last dimension, antiwar movements often point out the ill effects of nationalism suggesting that countries should not use wars to encourage imperialist or colonialist conquests. - eBook - ePub

- Immanuel Ness(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The Vietnam War—America's longest war—left much of Southeast Asia in ruins and divided Americans more than any other event in the nation's history since the Civil War. As the war unfolded on the other side of the globe—with horrific results—at home it gave rise to one of the most resilient, widespread, and diverse social protest movements. The antiwar movement began as a small series of protests, organized mostly by seasoned Old Left activists. Early antiwar actions were often discouraging affairs for planners and participants alike. They received scant media attention and were often overshadowed by even larger pro-war demonstrations.But years of persistent organizing transformed various scattered actions into a cohesive, mass, nationwide movement, with respectable adherents and a solid base of popular support. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, an increasing number of antiwar actions became more localized, grassroots efforts, as national antiwar coalitions fragmented, then regrouped into new entities, only to split again. Still, the movement would remain a potent force well into the 1970s. Within its ranks were senators and representatives, homemakers, college and high school students, civil rights activists, Maoists, countercultural youths, poets, Vietnam veterans, clergy, business executives, blue-collar workers, scientists, professors, African Americans, Latinos, soldiers and veterans, pacifists, draft resisters, and others.The movement drew support from hundreds of organizations, but no single group dominated it. Thus, it was far from monolithic. Within its ranks, liberal Democrats vied with Trotskyists. Student militants sometimes split with their seasoned elders. Leaders debated tactics, while ordinary participants created protest signs and banners that reflected their own personal concerns about the war. Countercultural youths who felt a natural rapport with the goals and aims of the movement drifted in and out of marches, while clean-cut supporters of Senator Eugene McCarthy (D-MN) turned their attention from Democratic Party campaigning to organizing the 1969 Moratorium protests. The killing of four students at Kent State University in Ohio and two students at Jackson State in Mississippi days later in May 1970 further intensified the divisions in American society and left the movement reeling but continuing. Vietnam veterans reenergized the movement when they marched on Washington in April 1971, briefly lobbied members of Congress, and then threw away their medals, ribbons, citations, and other military items on the steps of the nation's Capitol. - eBook - ePub

Hardhats, Hippies, and Hawks

The Vietnam Antiwar Movement as Myth and Memory

- Penny Lewis(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- ILR Press(Publisher)

Part I

THE ANTIWAR MOVEMENT

A Liberal Elite?

Passage contains an image

2

MIDDLE-CLASS CULTURES AND THE MOVEMENT’S EARLY YEARS

We call upon all men of good will to join us in this confrontation with immoral authority. Especially we call upon the universities to fulfill their mission of enlightenment and religious organizations to honor their heritage of brotherhood. Now is the time to resist.—“A Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority,” October 1967The great failure of the Anti-War Movement has been in its arrogance toward people who work with their hands for a living and its willingness not only to ignore them, but to go even further and alienate them completely.—Jimmy Breslin, “One Way to End the War,” New York Magazine , 1970In the next four chapters, I review the period of the war itself and trace the growth and development of antiwar sentiment and the many strands of the antiwar movement that developed. In this first chapter of part I, counterintuitive to my main argument, I detail how the movement began and expanded within a middle-class milieu. It is these years of movement activity, 1965–1967, that make the strongest case that antiwar action was concentrated among the relatively privileged sectors of US society. Nevertheless, as I explore in chapter 3, even in this early period, when we look within the movement organizations that grew at that time and among some of the most prominent antiwar activists, there was more economic diversity and attention to issues of class than is typically remembered. In chapters 4 and 5, I further develop this countermemory, one that differs from and challenges the dominant discourse regarding opposition to the Vietnam War in the United States.1Sociological studies often detail the complexity behind what appears simple on the surface, and this countermemory does just that: rather than simply replacing the controlling narrative, I hope to expand, question, reorder, and reprioritize its main patterns and threads. To begin with, if we look at who opposed the war, we see that working-class people did so as frequently as the middle class in the early years, and more so as time went by. - eBook - PDF

- Ian Taylor(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

That though, is not the full picture, as many other activists consciously con- nected their opposition to the Iraq War to an additional set of causes and/ or movements they either sympathised with or had been actively involved in. The peace movement Quite obviously, peace campaigning and anti-war activism are causes that share a great deal in common. For activists marching against say, any war with Iraq, the distinction between being anti-war and pro-peace often seemed a matter of pedantry. Yet the two causes have never been identical. One may be opposed to a particular war, and in that sense ‘anti-war’, without necessarily believing that war is wrong in all circumstances, which is, by definition, the hallmark of pacifism. And while nearly all military engagements that Britain has been party to since the Suez crisis of 1956 have drawn people out onto the streets to protest, albeit in wildly varying numbers, the idea that pacifism has ever constituted a large scale social movement in this country is altogether more tenuous. Committed pacifist organisations and initiatives, such as War Resisters International (whose UK branch was founded in 1923) and the Peace Pledge Union (est. 1934 and calling the individuals to pledge ‘not to support war of any kind’) have attracted only limited public support over the years. From this per- spective, the suggestion that opposition to the Iraq War (partially) grew out of ‘the long-term traditional peace movement’ may seem overstated, particularly so when one also considers that the StWC has never made any pretence of being a pacifist organisation (see Murray and German 2005: 49). Yet it may well be that this designation of the ‘peace movement’ is just too rigid. Given that every major military campaign since the Suez crisis has generated public protests, one can argue that there has long been an Anti-War Movement in Britain. - eBook - PDF

- John Dumbrell(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Red Globe Press(Publisher)

The Antiwar Movement 153 Antiwar protest intermingled in complex ways with mainstream antiwar electoral and congressional activity. During the course of the war, much of what I. M. Destler et al . (1984: 19) called ‘the liberal-moderate elite’ defected from the Cold War consensus and reconsti-tuted itself as the antiwar wing of the Democratic Party. Again, it can be argued that such defection was as much delayed by antiwar move-ment excesses as accelerated by the example of protest in the streets. What can reasonably be asserted, however, is that key elite figures were impressed by youthful protest, and came to appreciate the force even of its more extreme incarnations. With the opening-out of the movement during the Nixon years, liberal elite figures came to consti-tute one wing of the movement, no longer rather disengaged figures embarrassed by association with direct action. For example, Ernest Gruening, as an ex-senator, argued for sentence mitigation in relation to the convicted bomber of a war-related Wisconsin research centre in 1970. He recalled the tale of presidential deception which stretched back to the Tonkin Gulf Resolution (which, of course, he had opposed), describing it as ‘something we must bring home to the American people and which so fully justifies all acts of resistance to this war in whatever form it takes’ (Bates 1992: 413). Senator George McGovern reacted to the bombing of Capitol Hill itself in March 1971 as follows: ‘It is not possible to teach an entire generation to bomb and destroy others in an undeclared war abroad and not pay a terrible price in the derangement of our own society’ ( Congressional Quarterly Almanac 1971: 625). It is impossible to be precise about the effect of the antiwar protests on the morale of the US military and in hardening resolve in Hanoi. The antiwar movement had, in effect, a wing inside the American military. - eBook - ePub

Vietnam Documents: American and Vietnamese Views

American and Vietnamese Views

- George Katsiaficas(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter VI The Antiwar MovementDOI: 10.4324/9781315698366-6The American people have always been hesitant to become involved in foreign wars. During nearly every major war this country has waged, there has been a protest movement against it. Notable were the small but articulate movements against the Mexican War of 1846-1848 and the conquest of the Philippines from 1899-1901. Because of the public's unwillingness to go to war, even the country's entrances into World War I and World War II were delayed for years.With this historical background, it should not be surprising that a powerful antiwar movement existed in the United States during the Vietnam War, a movement that increasingly affected even the most conservative (pro-military) segments of the population. One of the reasons for the vast size of the antiwar movement was the simple fact, intuitively obvious to the most casual observer, that Vietnam posed no direct danger to American lives or property. Unlike other wars in the twentieth century where the enemy attacked or threatened the United States, no case could be made at any point that Vietnamese presented any direct danger to Americans. There was never even a hint that North Vietnam or the NLF might have nuclear weapons, chemical weapons, or any of the kinds of weapons that, more recently, it was thought that Saddam Hussein possessed in 1991.Although not well known, the impact of the antiwar movement on policymakers was critical in preventing the war's escalation. In November 1969, as we know today from Richard Nixon's memoirs, the president was prevented from using nuclear weapons against North Vietnam by the hundreds of thousands of people who marched in the United States. Years earlier, the power of protesters was felt by Lyndon Johnson. In August 1966, his military chiefs had urged massive bombing of Hanoi and Haiphong to speed the end of the war. To make their case, the generals arranged for Johnson to meet the Pentagon's computer experts, men who had calculated that three quarters of a million lives had been saved by using atomic bombs against Japan and that a similar number could be saved again through attacks on the North's urban areas. LBJ heard them out before interrupting, "I have one more problem for your computer—how long will it take 500,000 angry Americans to climb that White House wall out there and lynch their president if he does something like that?" - Ronald Edsforth(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

The movement included, among numerous other elements, contacts between women in Vietnam and the United States who worked in favor of “antiwar diplomacy” (Frazier 2017). It was also supported in the United States by movements for racial equality. Martin Luther King, Jr., spoke out against the Vietnam War in a famous 1967 speech at Riverside Church in New York City. But peace movements were not the only anti-colonial actors: Frantz Fanon, who joined the National Liberation Front in Algeria, was among a number of activists who fought with rebel movements against colonial and postcolonial impositions of power by Western nations. During the 1980s, many peace groups turned their attention to other issues as the last struggles for national liberation outside Soviet-controlled Eurasia ended. Countering a new round of the nuclear arms build-up, and opposing American interventions in support of dictatorships in Central and South America were the paramount peace issues in the United States. Additionally, numerous transnational peace groups in the United States and Europe actively supported the South African anti-apartheid movement (Klotz 1995). Many, including the WILPF, also became increasingly concerned with the ongoing conflict in the Middle East, and especially the continuing occupation of Palestinian territories seized by Israel in the 1967 war (Confortini 2012). The arms race between the United States and the former Soviet Union, as well as the spread of nuclear weapons to additional countries, provided a frequent source of peace movement mobilization and critique throughout the Cold War. In the 1970s, the United States and USSR negotiated two Strategic Arms Limitation (SALT) Treaties. The FIGURE 6.5: Dutch artists protest in Amsterdam against the Vietnam War, December 1966. Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain). 138 A CULTURAL HISTORY OF PEACE IN THE MODERN AGE antinuclear movement revived and quickly grew by the early 1980s to include millions of people around the world.- eBook - ePub

North Star

A Memoir

- Peter Camejo(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Haymarket Books(Publisher)

CHAPTER 7THE ANTIWAR MOVEMENTFrom the past few chapters it might seem as though much of my time in the 1960s was spent in confrontations with the Berkeley police. That is only part of the picture. Most of the time I was working to build civil rights actions or the anti-Vietnam War movement and, concurrently, to help build the YSA and the SWP. The student antiwar movement expanded rapidly in the years after 1965 and grew to massive proportions by 1969-70. Outside of civil rights actions it was the first time in my life that I was involved in a genuine struggle of millions of people.As with the entire book, this section on the antiwar movement is not meant to be a history. Recollecting my own experiences, I also want to outline the major political issues within the movement and my views on them both then and today. In addition to my recollections and diary I have drawn on Fred Halstead’s Out Now: A Participant’s Account of the American Movement against the Vietnam War.27 I knew Fred Halstead personally for years. A member of the SWP, he played a crucial role in the leadership of the major national demonstrations against the war and was the SWP’s presidential candidate in 1968.Differences within the Antiwar Movement

Depictions of the antiwar movement of the 1960s most often feature protestors with signs proclaiming “Out Now!” But it took several years of struggle to get that position accepted. We had to overcome the influence of liberals, mainly from the Democratic Party—the party in power—who were against unequivocal opposition to the U.S. war. The liberal Democrats tended halfheartedly to support the U.S. invasion under the guise of fighting “communism” but favored negotiations to end the conflict.Throughout the lifespan of the Vietnam antiwar movement, internal differences were constant and at times quite divisive. This tends to be the rule, not the exception, in movements for social change. But understanding the differences can be very useful (especially in those experiences of the 1960s and early 1970s) and teach us about building a massive pro-peace movement. Looking back some forty years later, I remain convinced that without the SWP/YSA current, the antiwar movement in the United States would have been weaker and its effectiveness limited. - eBook - ePub

Military Spending and Global Security

Humanitarian and Environmental Perspectives

- Jordi Calvo Rufanges(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

destroyer with new homes that could have housed more than 8,000 people…. This is not a way of life at all, in any true sense. Under the cloud of threatening war, it is humanity hanging from a cross of iron.(Eisenhower, 1953)The critique was further advanced in 1965 with the publication of an important article ‘Is there a Military Industrial Complex which prevents peace?’ (Pilisuk and Hayden), which was highly influential with the Anti-War Movement, arguing that ‘American society IS a military-industrial complex’. Among the many subsequent analysts of the war system and the nefarious linkages between the arms industry and government are Anatol Rapaport, Richard J Barnett, Fred Cook and Chalmers Johnson.But it was not simply the size and influence of the MIC that disturbed pacifists and progressives alike. It was also the uses to which it was being put overseas. In 1950–1953 the USA became bogged down in the Korean War, then even more deeply in SE Asia. The thrust towards foreign interventions and adventures continued through the latter part of the Cold War (Central America, Middle East, etc.) and persists today in the wake of the Somali, Afghan, Iraqi and other conflicts. All have elicited protests, and in some cases prolonged opposition movements.Opposition to military spending can be located as one component of this broader critique. The late 1960s and 1970s saw the rise of a huge Anti-War Movement in the USA and beyond, which itself was simply part of a highly diversified counter-culture. The period saw the rise of multiple and overlapping social movements: civil rights/anti-racism, women’s and gay liberation, environmental, etc.A good example of the new militancy is the Port Huron Statement, a 1962 political manifesto of Students for a Democratic Society. This wide-ranging statement, drafted by the late Tom Hayden, included a ‘New Left’ analysis of the Pentagon and the whole US political-economic system. It offered a robust critique of imperialism, military interventions and their justifications (which at that time meant ‘the Communist threat’; later, post-9/11, becoming ‘Terrorism’). Among other targets, the Statement attacked the permanent war economy, the concentration of defence spending among a few giant corporations, the large numbers of defence-dependent jobs and the triangular relations of business, military and political spheres. It rejected ‘A fiscal policy based upon defense expenditures as pump-priming ‘public works’ – without a significant emphasis on peaceful “public works” to meet social priorities and alleviate personal hardships’ (Students for a Democratic Society, 1964). - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- University Publications(Publisher)

Protests were fueled by a growing network of independently published newspapers (known as underground papers) and the timely advent of large venue rock'n'roll festivals such as Woodstock and Grateful Dead shows, attracting younger people in search of generational togetherness. The movement progressed from college campuses to middle-class suburbs, government institutions, and labor unions. The fatal shooting of four anti-war protesters at Kent State University cemented the resolve of many protesters. The Kent State killings saw campuses erupt all across the country; in May 1970 most universities were strike-bound, for example at Wayne State University. The late 1960s in the U.S. became a time of youth rebellion, mass gatherings and riots, many of which began in response to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., but which ignited in an atmosphere of open opposition to a wartime govern-ment. Veterans of the Vietnam War returned home to join the movement, including John Kerry, who spearheaded Vietnam Veterans Against the War and testified before Congress in televised hearings. Thirty years later, as a United States Senator, Kerry campaigned to become President of the United States, betraying a newfound reluctance to acknowledge his anti-war roots while playing up his stellar war record. Other U.S. veterans returned from the war saying that nobody wants to be in a war where people are suffering and dying, but that they found peace in their own minds by knowing they served their country. Some cited the words of George Washington's 1790 State of the Union Address: To be prepared for war is one of the most effectual means of preserving peace. Anti-war protests ended with the end of conscription and the final withdrawal of troops after the Paris Peace Accords were signed in 1973. Momentum from the protest organizations became a main force for the growth of an environmental movement in the United States. - April Carter(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

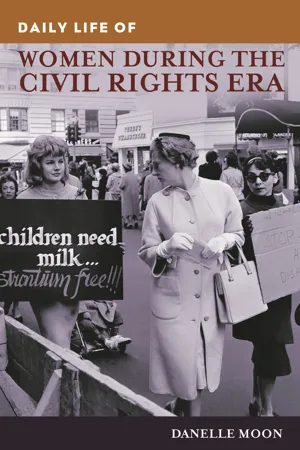

Protesters also tend to stress the brutality and immorality of the methods used by their government in waging the war: for example opponents of the Boer War in Britain pointed to the use of concentration camps. The mainspring of campaigns against specific wars has, however, been anti-imperialism. This has been combined with a simple human resistance to being drafted overseas to face death or injury, especially when victory looks uncertain and the cause dubious. Conscripts may simply rebel against the grimness of army life. All these elements were present in the protests against the French War in Algeria. During 1955 and 1956 there were widespread demonstrations and petitions, some conscripts refused to leave for Algeria and women lay down in front of troop trains. A committee set up in 1958 indicted French use of torture and repression against Algerians, and by 1960 intellectuals and students were protesting bitterly. Some potential conscripts went into hiding or escaped abroad, and they were openly supported in a public manifesto signed by 121 intellectuals. 7 War resistance can, however, be extended to active support for those justly fighting for independence. In France the highly controversial Jeanson network offered direct assistance to the Algerian National Liberation Front, and in the eyes of many discredited the wider opposition. So not all forms of resistance to specific wars can count as being part of a ‘peace movement’. Anti-imperialism is not the only reason for opposing wars as unjust. Just War doctrine and popular perceptions distinguish between genuinely defensive wars and acts of aggression. So it is not surprising that the 1982 Israeli incursion into the Lebanon to crush the Palestine Liberation Organization, which could not, like the wars of 1967 and 1973, be seen as a legitimate response to a military threat from Arab states, provoked major public demonstrations against the government- Danelle Moon(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

Antiwar Movement, Race, Ethnicity, Religion, and Sexuality 197 Television helped to transform the antiwar movement. In con- trast to World Wars I and II and the Korean War, television brought home the reality of the violence and carnage of the war. Just as the television coverage of southern opposition to desegregation raised the national consciousness of the problem of racism, the imagery of wounded soldiers and the devastation on the civilian population in Vietnam, escalated a fierce antiwar movement. The expansion of the war and the mandatory draft fueled a more violent domestic movement. Meanwhile, the increase in militancy replaced the non- violent protest modeled by Martin Luther King Jr. The rise of the New Left, represented by the SDS and the FSM, the Black Panthers, and the domino effect of race riots in cities across the United States, challenged the status quo of white America, while attacking corpo- rate greed, capitalism, and imperialism. Amidst all of the unrest, a counterculture emerged with young men and women living in communes, smoking dope, and tripping on LSD. Sexual freedom and the availability of the birth control pill pushed the sexual revolution forward, and the music and drug culture offered an escape for young adults. Together these devel- opments contributed to a growing women’s liberation movement that focused on a new female consciousness and the eradication of women’s sexual oppression. Young adults began to challenge the traditions and values of their parents, and they generally dis- trusted the ability of adults to change the world, while a growing population of activists showed contempt for law enforcement and distrusted government authorities to enforce basic civil rights. The murders of Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X reinforced these feelings of distrust in the government and law enforcement.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.