History

Birmingham Campaign

The Birmingham Campaign was a pivotal civil rights movement in 1963, organized by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and led by Martin Luther King Jr. The campaign aimed to end segregation and racial discrimination in Birmingham, Alabama, through nonviolent protests and civil disobedience. The use of peaceful demonstrations and the resulting violent response from authorities drew national attention and ultimately led to significant desegregation efforts.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

6 Key excerpts on "Birmingham Campaign"

- eBook - PDF

Martin Luther King and the Rhetoric of Freedom

The Exodus Narrative in America's Struggle for Civil Rights

- Gary S. Selby(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Baylor University Press(Publisher)

Nevertheless, for a time, the campaign had succeeded in mobilizing virtually the entire black community in organized, large-scale action against segregation, revealing the protesters’ willingness to go to jail for the cause and demonstrating the economic power that the black com-munity could wield through boycotts and mass protests. King and the other SCLC leaders emerged from their experience in Albany, com-bined with what they had witnessed in the sit-in movement and the Freedom Rides, determined to find a location where there was a highly committed, mobilized black community that could direct its action against economic rather than political leaders, where the SCLC could operate without competition from other organizations, and where the local police force was of such a character that protesters would pro-voke the kind of violent reaction that would gain the attention of the media and prod the federal government to take action. That place was Birmingham. M ARCHING TO F REEDOM : T HE B IRMINGHAM C AMPAIGN The Birmingham Campaign—what McWhorter called the “climactic battle of the Civil Rights Movement”—began in April, 1963, with a series of demonstrations designed to augment a boycott of the city’s segregated downtown department stores already in progress. In the first phase of the effort, small groups of protesters would arrive down -town and engage in sit-ins or pickets and would be promptly arrested by Bull Connor’s police force. These protests, however, soon gave way to what became the campaign’s chief weapon, the march, which sent waves of demonstrators walking toward city hall, only to be arrested and taken to jail. The first march in the Birmingham Campaign, led by Fred Shut -tlesworth, a local leader and head of Birmingham’s local protest organization, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR), took place on Saturday, April 6, and included some thirty volunteers who were all arrested. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- The English Press(Publisher)

The goals may not have been specific enough. Pritchett contained the marchers without violent attacks on demon-strators that inflamed national opinion. He also arranged for arrested demonstrators to be taken to jails in surrounding communities, allowing plenty of room to remain in his jail. Prichett also foresaw King's presence as a danger and forced his release to avoid King's rallying the black community. King left in 1962 without having achieved any dramatic victories. The local movement, however, continued the struggle, and it obtained significant gains in the next few years. Birmingham Campaign, 1963–1964 Bill Hudson's image of Parker High School student Walter Gadsden being attacked by dogs was published in The New York Times on May 4, 1963. The Albany movement was shown to be an important education for the SCLC, however, when it undertook the Birmingham Campaign in 1963. Executive Director Wyatt Tee Walker carefully planned strategy and tactics for the campaign. It focused on one goal— the desegregation of Birmingham's downtown merchants, rather than total desegregation, as in Albany. The movement's efforts were helped by the brutal response of local authorities, in particular Eugene Bull Connor, the Commissioner of Public Safety. He had long held much political power, but had lost a recent election for mayor to a less rabidly segregationist candidate. Refusing to accept the new mayor's authority, Connor intended to stay in office. ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ The campaign used a variety of nonviolent methods of confrontation, including sit-ins, kneel-ins at local churches, and a march to the county building to mark the beginning of a drive to register voters. The city, however, obtained an injunction barring all such protests. Convinced that the order was unconstitutional, the campaign defied it and prepared for mass arrests of its supporters. King elected to be among those arrested on April 12, 1963. - eBook - PDF

Race in the American South

From Slavery to Civil Rights

- David Brown, Clive Webb(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Edinburgh University Press(Publisher)

The presence of the SCLC leader led the Albany Movement to increase its demands, which in turn stiffened the resistance of white officials. 20 By August 1962, nine months of demonstrations had done nothing to breach the defences of Jim Crow in Albany. King cut his losses and abandoned the com-munity. Although the Albany Movement continued throughout the 1960s to campaign for racial reform, it never fully regained momentum. The civil rights movement faced an uncertain future after the failure of the Albany campaign. Internal dissent mounted, with some activists expressing their disillusionment with both the tactics of the SCLC and the leadership of 304 RACE IN THE AMERICAN SOUTH Martin Luther King. No issue weighed more heavily on the minds of activists than their inability to force federal government intervention in Albany. The refusal of the Kennedy administration to take sides in the dispute had doomed the protests to defeat. What the movement needed was a demon-stration of the moral urgency of the race issue that would push it to the top of the domestic political agenda. That breakthrough came as a result of an audacious campaign by the SCLC in the notoriously racist city of Birmingham, Alabama. Birmingham had the reputation of being the most segregated city in the United States. A strong recruiting ground for the Ku Klux Klan, its violently repressive political climate had earned it the bleak sobriquet ‘Bombingham’. The principal force of racial terror was Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene ‘Bull’ Connor, who used his command of the police to intimidate, assault and arrest those who dared promote reform. Yet it was precisely because of its appalling reputation that Birmingham was chosen as the target of the SCLC campaign. - T. Newell(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

In mid-June, President Kennedy gave a national address on civil rights, uttering words King had despaired of hearing: “We are confronted primar- ily with a moral issue.” Kennedy introduced civil rights legislation a week later. Earlier plans for a March on Washington took concrete shape, now concentrated on pressuring Congress to pass Kennedy’s bill. On August 28, a peaceful crowd of well over 200,000 and King’s concluding “I Have a Dream” speech demonstrated for a national TV audience that blacks were neither outsiders nor extremists. King would later note that the number of SCLC affiliates jumped from 85 to 110 that summer, and “hundreds of national civic, religious, labor and professional organizations speaking for tens of millions . . . called upon their supporters to join the demonstrations.” In the ten weeks following Birmingham, 758 demonstrations led to 14,733 arrests in 186 American cities as the demand for racial progress spread virally. By the end of the year, King had traveled more than a quarter million miles, made some 350 speeches, and would be featured in January as Time’s Man of the Year. The Nobel Peace Prize would follow in 1964, when the Civil Rights Act was finally passed in homage to the slain Kennedy. 97 The Letter in History Birmingham was a turning point, and the Letter signaled that change and became its manifesto. The shift in national consciousness evoked in the Letter formed the psychological foundation for decades of (often halting) progress. A Gallup Poll released on April 3, 1963, at the start of the Birmingham Campaign, showed that only 4 percent of Americans considered “racial problems” one of the nation’s “most important problems.” By October 2, that figure jumped to 52 percent and “racial problems” ranked first. 98 Yet the Letter also offered a practical change strategy.- eBook - ePub

The Civil Rights Movement

A Documentary Reader

- John A. Kirk(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Chapter 9 The Selma Campaign and the Voting Rights Act of 19659.1 William C. Sullivan (Anonymous), Letter to Martin Luther King, Jr, 1964

Just as Martin Luther King, Jr and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) had used the 1963 Birmingham Campaign to highlight the brutality of segregation and to place pressure on the federal government to pass desegregation legislation, in 1965 they used the Selma campaign to highlight the brutality of disenfranchisement and to place pressure on the federal government to pass legislation to enforce and strengthen black voting rights. In Selma, approximately half the population was black, but 99% of registered voters were white. In contrast to the long‐term grassroots community organizing model of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), King and the SCLC’s trademark was the short‐term community mobilization model that sought to bring about dramatic conflict and a federal response. In no small part, this approach was driven by the resources that King and the SCLC had at their disposal. Without SNCC’s cadre of student volunteers, with limited funds, and with King’s national standing as its greatest asset, the SCLC saw its short‐term, intense burst of activism campaigns as its most effective instrument for change.The increasing efforts by the federal government to prevent such campaigns from taking place were testimony to their effectiveness. The FBI in particular took an interest in King’s activities. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover early on decided that King was “no good” and made a number of public criticisms about him. With the approval of Attorney General Robert Kennedy, the FBI began wiretapping King’s phones. Then, moving beyond their legal mandate, they began planting illegal bugging devices in King’s hotel rooms. In November 1964, the white FBI assistant director William C. Sullivan sent a taped collection of such illicitly obtained recordings that allegedly contained dirty jokes, bawdy remarks, and the sound of people engaging in sexual intercourse, to SCLC headquarters. The letter that accompanied it, below, appeared to ask King to commit suicide or to withdraw from public life to prevent him from being exposed as a “fraud.” The move seems to have been an attempt to prevent the Selma campaign from taking place. The package finally made it to King’s home address in early January 1965, where King’s wife, Coretta Scott King, listened to the tape. She dismissed its contents as “just a lot of mumbo jumbo.” A 1977 lawsuit by one of King’s associates led to a court decision to seal the contents of the recordings until 2027. - eBook - ePub

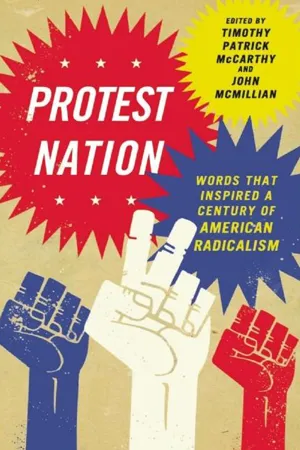

Protest Nation

Words That Inspired a Century of American Radicalism

- Timothy Patrick McCarthy, John McMillian, Timothy Patrick McCarthy, John McMillian(Authors)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- The New Press(Publisher)

Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama: The Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution (2001).April 16, 1963 My Dear Fellow Clergymen:While confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling my present activities “unwise and untimely.” Seldom do I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. If I sought to answer all the criticisms that cross my desk, my secretaries would have little time for anything other than such correspondence in the course of the day, and I would have no time for constructive work. But since I feel that you are men of genuine good will and that your criticisms are sincerely set forth, I want to try to answer your statement in what I hope will be patient and reasonable terms.I think I should indicate why I am here in Birmingham, since you have been influenced by the view which argues against “outsiders coming in.” I have the honor of serving as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, an organization operating in every southern state, with headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia. We have some eighty-five affiliated organizations across the South, and one of them is the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. Frequently we share staff [and] educational and financial resources with our affiliates. Several months ago the affiliate here in Birmingham asked us to be on call to engage in a nonviolent directaction program if such were deemed necessary. We readily consented, and when the hour came we lived up to our promise. So I, along with several members of my staff, am here because I was invited here. I am here because I have organizational ties here.But more basically, I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eighth century B.C. left their villages and carried their “thus saith the Lord” far beyond the boundaries of their home towns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far corners of the Greco-Roman world, so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my own home town. Like Paul, I must constantly respond to the Macedonian call for aid.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.