History

Stokely Carmichael

Stokely Carmichael was a prominent figure in the American civil rights movement. He served as the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and later became a leading advocate for Black nationalism. Carmichael popularized the term "Black Power" and emphasized the importance of self-determination and self-defense for African Americans in the struggle for equality.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Stokely Carmichael"

- eBook - PDF

American Voices

An Encyclopedia of Contemporary Orators

- Bernard K. Duffy, Richard Leeman, Bernard K. Duffy, Richard Leeman(Authors)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

46 Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Toure) (1941-1998) Stokely Carmichael (KWAME TOURE) (1941-1998) African American Civil Rights Leader ROBERT E. TERRILL It has often been noted that the life of Stokely Carmichael closely parallels the history of the 1960s civil rights movement in the United States. His own evolution from nonviolent resister to Pan- Africanist revolutionary matches one arc of devel- opment within the movement as a whole. His rhet- oric, of course, had much to do with both his presence at many of the crucial moments in the movement's history and his influence at those mo- ments. Well-educated, articulate, attractive, and apparently fearless, Carmichael rose to promi- nence within the civil rights movement in part be- cause of his ability to speak effectively to a wide range of audiences, from illiterate Black share- croppers to privileged white college students. And he was willing to say things that his Black audi- ences might be thinking but would not have said out loud, things certain to enrage or frighten his white audiences. Carmichael was born on June 29, 1941, in Port of Spain, Trinidad. His parents immigrated to New York when he was a toddler; Stokely and other members of his family followed in 1952. Although Carmichael would gain his notoriety in part through his willingness to denounce the 'American dream" as an instrument of racist op- pression, his father strongly believed in it, even though his hard work was never able to lift his family out of poverty. As Carmichael put it in a 1967 interview with Gordon Parks in Life mag- azine: My old man believed in this work-and- overcome stuff. He was religious, never lied, never cheated or stole. He did carpentry all day and drove taxis all night. . . . May Charles [Stokely's mother] had to bribe an official with 50 bucks and a bottle [of] perfume to get him into the union. - eBook - PDF

- Kini-Yen Kinni(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Langaa RPCIG(Publisher)

Stokely Carmichael the great black activist, organizer, and freedom fighter traced the dramatic changes in his own consciousness and that of black Americans that were at the base of the founding of Black Power from the Civil Rights Movement that was tied to the evolution of Pan Africanism. Stokely Carmichael (1971) insisted that: “The destiny of African Americans could not be separated from that of oppressed people the world over, Carmichael’s Black Power principles insisted that blacks resist white brainwashing and redefine themselves. He was concerned not only with racism and exploitation, but with cultural integrity and the colonization of Africans in America. In these essays on racism, Black Power, the pitfalls of conventional liberalism, and solidarity with the oppressed masses and freedom fighters of all races and creeds, Carmichael addresses questions that still confront the black world and points to a need for an ideology of black and African liberation, unification, and transformation.” Kwame Ture(Stokely Carmichael) is celebrated as that dedicated and ardent Pan Africanist who stressed on the importance of studying History, especially African History as Kwekudee (2012) quotes also Carmichael insisting that: “The Importance Of Studying History, Stokely Carmichael, breaking down the paradigm of social and cultural racism which was historically backed through scientific racism from the 18th century till today in some places. However this ideological view is on its deathbed. So its proponents are desperately reevaluating, revising, and rationalizing the justifications for obsolete racist views. Yet, they’re failing miserably. They’re facing the inevitable IDEOLOGICAL EXTINCTION. Furthermore Kwame reemphasizes the importance of people on the continent and Diaspora knowing their history. He emphasizes the importance of Africa being the Centre of history for the people on the continent. - eBook - PDF

Icons of African American Protest

Trailblazing Activists of the Civil Rights Movement [2 volumes]

- Gladys L. Knight(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

King and the other conservative black leaders were confounded. But his audience went wild with excitement. The term spread like wildfire across the nation. Black Power organiza- tions and leaders emerged, advancing such concepts as militancy, separa- tism, and black pride. For the next few years Carmichael was a high-profile leader in the move- ment he had started. But in 1969 he moved to Africa, because the Black Power Movement in America, radical as it was, had failed to meet his expectations. He wanted black organizations to sever all ties with whites. In Africa, Carmichael abandoned Western attire and changed his name to Kwame Ture. His new moniker melded the names of two African leaders, Ahmed S ekou Tour e, a prime minister of Guinea, and Kwame Nkrumah, the president of Ghana. Carmichael married twice and had a son. He con- tinued to lecture, to write, and propound his socialist and Pan-Africanist views until his death in 1998. CHILDHOOD Early Years in Trinidad Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael was born on July 29, 1941, in Port of Spain, Trinidad. His parents were Adolphus and Mabel Carmichael. He 54 Icons of African American Protest had two sisters, Umilta and Lynette. The blacks who lived in Trinidad and the other Caribbean islands were, as in America, a product of the slave trade in Africa. When Stokely was born, Trinidad was still a crown colony, i.e., a country controlled by the British government. However, the spirit of resistance in Trinidad was alive and well. Slavery and the system of indentured servitude (which affected racial groups such as African descendants, the Chinese, and the East Indians) were diminished by tactics involving nonviolent demon- strations and officially abolished in 1838. Though free, blacks were still oppressed by the colonial rule of England. - eBook - PDF

The New Black History

Revisiting the Second Reconstruction

- E. Hinton(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

Near the end of his life, American democracy’s glaring contradic- tions seemed to pale in comparison with the crisis of African nation-states that unfolded in the post–Black Power era. But for Ture, opportunities remained hidden beneath each setback and, even at its worst, Africa held untold poten- tial. While such patience struck some as naive, Ture remained confident that his political path had helped shape a better world and to his final breath believed in, indeed remained ready for, revolution. Ture’s activism and influence spanned from Harlem to the Mississippi delta out west to California’s Bay Area and the wider worlds of Europe, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Most often, however, Ture’s presence (except for the obligatory recounting of the Meredith March) is either ignored or demonized in the increasingly vast literature on the civil rights movement. The young Stokely Carmichael’s pivotal role in reshaping, scandalizing, and transforming American democratic traditions is, inevitably, lost. Ture’s own reticence to acknowledge the depth and complexity of his political journey (even in his own autobiography) at times contributed to the lack of serious scholarly interrogation of his extraordi- nary life. But there were other reasons as well, most notably Ture’s unapologetic commitment to a style of black radicalism that made him seem out of touch with the political austerity that followed the heady years of the 1960s. Over four decades after the twenty-five-year-old Stokely Carmichael unleashed words sharp enough to cut through the thick humidity of a Mississippi evening, understand- ing the political experiences (and recovering the historical context) that led to this momentous declaration, and the events after, will transform our comprehension of not only the civil right and Black Power eras but the larger postwar freedom struggles that inspired and shaped these movements. Notes 1. For a comprehensive examination of the movement see Peniel E. - eBook - PDF

- Richard T. Schaefer(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications, Inc(Publisher)

There, he became an aide to the Guinean prime minister, Ahmed Sékou Touré, and helped establish the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party. In 1971, he wrote the book Stokely Speaks: Black Power Back to Pan-Africanism. The book expounded an explicitly Socialist Pan- African vision, which he retained for the rest of his life. In 1978, he changed his name to Kwame Ture to honor the African leaders Kwame Nkrumah and Ahmed Sékou Touré. In 1984, after the death of Touré, Carmichael was arrested by the new military regime and charged with trying to overthrow the government. However, he spent only 3 days in prison and was then released. In 1996, Carmichael was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He was treated in Cuba and received financial help for his treatment from Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan. Carmichael finally succumbed to cancer on November 15, 1998, in Conakry, Guinea. Matthew W. Hughey See also Black Nationalism; Black Panther Party; Black Power; Congress of Racial Equality (CORE); Marxism and Racism; Newton, Huey; Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Further Readings Blake, John. 2004. Children of the Movement. Chicago, IL: Lawrence Hill Books. British Broadcasting Company. 1998. Black Panther Leader Dies. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/ americas/215245.stm Carmichael, Stokely. 1971. Stokely Speaks: Black Power Back to Pan-Africanism. New York: Random House. Carmichael, Stokely and Charles V. Hamilton. 1967. Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America. New York: Vintage Books. Garrow, David J. 1986. Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. New York: Vintage Books. Ture, Kwame and Ekwueme Michael Thelwell. 2003. Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture). New York: Scribner’s. CASTE What makes Indian society unique is the phenomenon of caste. - eBook - ePub

Say It Plain

A Century of Great African American Speeches

- Catherine Ellis, Stephen Drury Smith(Authors)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- The New Press(Publisher)

10. Stokely Carmichael (1941–1998) Speech at University of California, BerkeleyOctober 29, 1966Stokely Carmichael was the brilliant and impatient young civil rights leader who, in the 1960s, popularized the phrase “black power.” Carmichael was initially an acolyte of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. and his philosophy of nonviolent protest. Carmichael became a leader in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), but was radicalized when he saw peaceful protestors brutalized in the South.In the mid 1960s, Carmichael challenged the civil rights leadership by rejecting integration and calling on blacks to oust whites from the freedom movement. Following his arrest during a 1966 protest march in Mississippi, Carmichael angrily demanded a change in the rhetoric and strategy of the civil rights movement. “We’ve been saying ‘Freedom’ for six years,” Carmichael said. “What we are going to start saying now is ‘Black Power.’ ” 1Historian Adam Fairclough writes that King was “aghast” at Carmichael’s use of a slogan that sounded so aggressive. “Black power” was condemned by whites as a motto for a new form of racism. Some whites feared that black power was a call for race war. King urged Carmichael to drop the phrase but he refused.2 NAACP leader Roy Wilkins condemned the slogan as “the father of hate and the mother of violence,” predicting that black power would mean “black death.” 3Fellow civil rights organizer John Lewis, later a Democratic congressman from Georgia, remembered Carmichael as tall, lanky, and up-front. “He didn’t wait to be asked his opinion on anything—he told you and expected you to listen,” Lewis wrote. The two became estranged when Carmichael toppled Lewis from the SNCC chairmanship. 4In 1966 and 1967, Carmichael toured college campuses giving increasingly belligerent speeches. He coauthored a radical manifesto titled Black Power, in which he argued that civil rights groups had lost their appeal to increasingly militant young blacks. The movement’s voice, he wrote, had been hopelessly softened for “an audience of middle class whites.” 5 - eBook - ePub

Africa in Black Liberation Activism

Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael and Walter Rodney

- Tunde Adeleke(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

2 Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) Existentialist African Africans today, irrespective of geographical location, have a common enemy and face common problems. We are the victims of imperialism, racism, and we are a landless people. (Stokely Carmichael) The African connection that Malcolm X emphasized and the internationalization that was so crucial to his platform was, in Stokely Carmichael’s conviction, precisely the direction the black struggle should be headed. Malcolm had witnessed, and in fact his ideas had watered the soil of, the sprouting Black Power movement. He had foreseen the deepening crisis and growing disaffection and militancy of the urban youth, and had in fact predicted that 1965 was going to be a critical year that would witness eruption of the simmering conditions. Malcolm did not live to witness the riots in Watts and the “long hot summer” of 1965. Carmichael did. He was very much in the vanguard of the disaffected urban youth rebellion that gripped the nation that summer. 1 Malcolm X had no more dedicated and effective protégé than Carmichael. In fact, it would seem that his entire life was a conscious attempt to follow the footprints of Malcolm: to finish what he had started. Malcolm had no greater admirer in the generation of black student activists (SNCC) that he held in such high regard. Malcolm spoke to their frustrations, their burning desires, and seeming impatience with what they perceived as the slow pace of change, and the failure or inability of the mainstream civil rights movement to confront America. Consequently, when Carmichael subsequently veered in the direction of Africa, he would predicate his turn on precisely the same expansive and colored cosmopolitan rationale adduced by Malcolm and earlier generations of activists - eBook - PDF

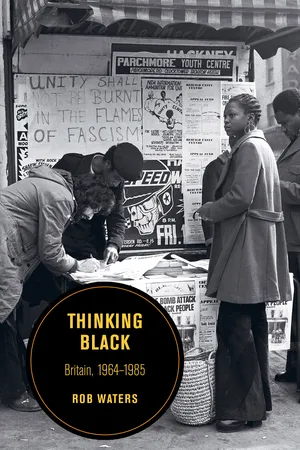

Thinking Black

Britain, 1964-1985

- Rob Waters(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

15 in july 1967, Stokely Carmichael came to London. A civil rights activist in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Carmichael had gained international fame—or infamy—for his call for “Black Power” at a rally in Greenwood, Mississippi, in June 1966, popularizing the slogan that came to define the global politics of radical blackness for over a decade. 1 He visited London at the height of his fame, at the start of a five-month world tour that his biographer describes as “the culmination of his personal desire and political need to forge relationships with global revolutionaries.” 2 For black Britons, as the Barbadian poet Edward Brathwaite later recalled, Carmichael’s visit “magnetized a whole set of splintered feelings that had for a long time been seeking a node.” 3 Interviewing London’s Black Power groups for her undergraduate sociology degree at the University of Edinburgh in 1969, the Trinidadian student Susan Craig found his visit remembered as “the single crystallizing experience which carried them over the threshold into ‘ becoming Black .’ Two years later, the fervour with which Carmichael and his message were received was spontaneously described by many mili-tants as a ‘conversion.’ ” 4 Carmichael was a confrontational black man in London, and, significantly, a Trinidadian by birth. “Here, for the first time, was ‘one of us’ telling the whites ‘where to get off,’ ” Craig wrote. 5 Craig’s interviewees were not alone in their “conversion” to blackness through Black Power. - eBook - ePub

The debate on black civil rights in America

Second edition

- Kevern Verney(Author)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- Manchester University Press(Publisher)

47Reflecting other developments in African American historiography, several post-millennium studies examined the contribution of women and the role of gender in the black power movement. In Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era (2017) Ashley Farmer highlighted the extent to which they were inspired by women activists of previous generations. Similarly, in analysing representations of masculinity in the black press D’Weston Haywood found that the macho rhetoric of male black power activists had its roots in ‘an influential masculinized discourse constructed in the black press over the course of decades’. In short, just as historians had acknowledged the existence of a ‘long civil rights movement’, there was now recognition that there was also a long black power movement.48The nature and importance of African American cultural achievement in the black power movement was a topic that was given rather more attention by scholars by the 1990s. The journalist Thomas Hauser's Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times (1991) provided an authoritative biography of the era's best known sporting icon. King of the World (1999) by David Remnick contributed another well researched and detailed study of Ali, whereas Mike Marqusee, Johnny Smith and Randy Roberts focused on his involvement with the Nation of Islam and his contribution to the African American freedom struggle.49In 1992 the historian William L. Van Deburg published New Day in Babylon, a study of the black power movement and American culture between the mid-1960s and the mid-1970s. Five years later, in Black Camelot, he followed this up with an analysis of African American cultural icons of the 1960s and 1970s. In 1999 Komozi Woodard contributed a study on the black power cultural nationalist Amiri Baraka (Le Roi Jones). Julius E. Thompson examined the work of Dudley Randall and the black arts movement, and in 2003 Scot Brown provided a much-needed full-length study of Maulenga Karenga and his nationalist-cultural ‘US’ organization.50 - eBook - ePub

Mobilising Classics

Reading radical writing in Ireland

- Fiona Dukelow(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Manchester University Press(Publisher)

He changed his name to Kwame Ture in honour of his two political heroes – Kwame Nkrumah and Sékou Touré. In July 1969, three months after he moved to Africa, he made public his resignation from the Black Panther Party because of what he called ‘its dogmatic party line favoring alliances with white radicals’ (Carmichael and Thelwell, 2003: 668). In Africa he organised the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party and insisted that ‘Black power can only be realized when there exists a unified socialist Africa’ (Ture and Hamilton, 1992: 199). His marriage to Miriam Makeba the South African activist and singer symbolised his developing Pan-Africanism (Carmichael, 2007: 221–7). His journey also, of course, symbolised the union of Black radicalism internationally and no doubt presented the nemesis of White Power – a synthesis of Black liberation movements at home and abroad across Africa, the Caribbean and the USA. Kwame Ture worked in support of these principles until he died of prostate cancer in Guinea in 1998. His activism spanned a continuum of evolving Black Liberation politics throughout the 1960s like no other individual – ranging from reformism to US Black nationalism to Africanist and socialist internationalism. He was a leader in SNCC, the Black Panther Party and the All African People’s Revolutionary Party. In later life he remained critical of the supposed economic and electoral progress made by African Americans since the 1960s. We can only speculate as to what his reaction to Obama’s election might have been. Kwame Ture’s co-author Charles Hamilton was from an African American academic background. His experiences and struggles as a radical young academic in Booker T. Washington’s segregated Tuskegee Institute are detailed in Black Power. After he wrote Black Power, Charles Hamilton became one of the first African Americans to hold a chair at an Ivy League Institution (Rich, 2004)

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.