History

Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Hamer was a prominent figure in the Civil Rights Movement, known for her activism and leadership in the fight for voting rights and racial equality. She co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and played a crucial role in challenging racial segregation and discrimination. Hamer's powerful speeches and unwavering commitment to justice made her a respected and influential voice in the struggle for civil rights.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

7 Key excerpts on "Fannie Lou Hamer"

- eBook - PDF

Icons of African American Protest

Trailblazing Activists of the Civil Rights Movement [2 volumes]

- Gladys L. Knight(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

Fannie Lou Hamer (1917–1977) Library of Congress Fannie Lou Hamer was a sharecropper turned civil rights activist. She par- ticipated in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, and many other community and civil rights projects. Most of Hamer’s campaigns took place in her home state of Mississippi during the 1960s and 1970s. Voting rights, political power, social welfare, and assistance programs for African Americans were focal points of her ca- reer. Following her testimony before the Credentials Committee at the 1964 Democratic Convention, this hometown hero became a nationally known leader who would go on to make significant contributions to the Civil Rights Movement. Fannie Lou Hamer had little in common with the heavyweights of the civil rights struggle such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Roy Wilkins, James Farmer, and others. She neither looked nor sounded like the typical civil rights leader. She had no college degree—indeed, she had only six years of formal education. She came from a severely impoverished family in the Deep South, where racism and anti-black violence were notorious. The world in which Hamer grew up was a harsh one, where local author- ities either tolerated, ignored, or abetted atrocities against blacks. From childhood on, she had experienced firsthand racism, violence, and poverty. As a result, she was able to relate to and effectively communicate with downtrodden blacks. This made her one of the most valuable activist lead- ers in African American protest. When Hamer spoke before an audience, she did so using the vernacular of the rural people. She drew from her religious experiences and knew how to use the soul-stirring old-time spirituals that were an essential part of the movement. Her down-home personality had a compelling and dramatic effect on those who heard her. - eBook - ePub

- Peter J. Parish(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

H

Civil rights campaignerHamer, Fannie Lou 1917–1977Collum, Danny, “Stepping Out into Freedom: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer,” in Sojourners , 12 December 1982Crawford, Vicki L., Jacqueline Anne Rouse, and Barbara Woods (editors), Women in the Civil Rights Movement: Trailblazers and Torchbearers, 1941–1965 , New York: Carlson, 1990Garland, Phyl, “Builders of a New South: Negro Heroines of Dixie Play Major Role in Challenging Racist Traditions,” Ebony , 21, August 1966Grant, Jacquelyn, “Civil Rights Women: A Source for Doing Womanist Theology,” in Women in the Civil Rights Movement (see Crawford, above)Locke, Mamie, “Is This America? Fannie Lou Hamer and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party” in Women in the Civil Rights Movement (see Crawford, above)Mills, Kay, This Little Light of Mine: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer , New York: Dutton, 1993Peterson, Franklynn, “Sunflowers Don't Grow in Sunflower County,” Sepia , February 1970Peterson, Franklynn, “Mother of Black Women's Lib,” Sepia , December 1972Reagon, Bernice Johnson, “Women as Culture Carriers in the Civil Rights ovement: Fannie Lou Hamer,” in Women in the Civil Rights Movement (see Crawford, above)In the early 1960s, when the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) went into the rural Deep South to challenge existing racial structures, they hoped to create opportunity, or spaces, in which local grassroots black leadership might grow and develop. Testimony to SNCC's faith in this approach to combating institutionalized racism was provided by the emergence of Fannie Lou Hamer, who became one of the most inspirational and influential figures of the black freedom movement. The twentieth child of poor Mississippi Delta sharecroppers, herself a sharecropper and timekeeper for many years on a local plantation, Hamer went on to become a voter registration worker; a SNCC field secretary; a founder, vice-chair, and candidate for office of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party; and a welfare rights activist. - Hasan Kwame Jeffries(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- University of Wisconsin Press(Publisher)

In fact, it deepened her commitment to fighting for freedom. With a powerful singing voice and keen organizing skills, Mrs. Hamer partnered with young SNCC organizers to help transform Mississippi by challenging the power of southern segregationists and northern liberals. Without Mrs. Hamer, the movement in Mississippi would not have been nearly as effective as it was. So, having gotten nowhere with Medgar Evers, I decided to shift gears. Nodding toward the library, I asked, “How about Fannie Lou Hamer? Who can say something about her?” But once again, no one said a word. 15 Cobb / Who Is Fannie Lou Hamer? By then, my ride had arrived, and as I got up I pointed at the library and told the kids that black Mississippians made a big difference in the civil rights struggle and that Mrs. Hamer was one of the people they needed to learn about if they wanted to understand how those African Americans did it. She was a native Mississippian, I added for emphasis. I also told them that I would be happy to share my remembrances of Mrs. Hamer since I knew her personally. Just then, as I was about to tell a story that I thought might bring them back to the school’s steps when I returned in few days, one of the kids leapt to his feet and in sheer amazement exclaimed, “Mr. Cobb! You was alive back then!” The student’s surprise at discovering that I knew Mrs. Hamer per- sonally is easy to understand. After all, her name was chiseled into the Civil rights activist and Mississippi Freedom Demo- cratic Party delegate Fannie Lou Hamer speaking at the Democratic National Con- vention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on August 22, 1964. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Divi- sion, LC-DIG-ppmsc-01267 [digital file from original negative] LC-U9-12470B-17) 16 Part One: Dispatches from the Frontline facade of a public building, albeit a modest one. For a middle school student at the beginning of the twenty-first century, the 1960s were an- cient times.- eBook - ePub

Women, War, and Violence

Topography, Resistance, and Hope [2 volumes]

- Mariam M. Kurtz, Lester R. Kurtz, Mariam M. Kurtz, Lester R. Kurtz(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

8For Fannie Lou Hamer—as for many women—the hope and desire for fulfillment could not be found on a road that led to separation from men. She would not have understood what was meant by the Redstockings Manifesto statement of the late 1960s radical feminists identifying the agents of oppression as men. Nor did she see herself as the “slave of a slave,” as some black women feminists phrased it (Beal, 1970, p. 343). Alienation from male partners—whether fathers, brothers, or sons—or opposition to men was unthinkable to Mrs. Hamer, who had a different slant: “I’m not hung up on this about liberating myself from the Black man, I’m not going to try that thing. I got a Black husband, six feet three, two hundred and forty pounds, with a [size] 14 shoe, that I don’t want to be liberated from” (Hamer, 1970, p. 612).Figure 25.4Fannie Lou Hamer’s leadership in the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party brought to national attention the abuses and violations faced by Mississippi’s black citizens, when she testified in August 1964 at the Democratic National Convention, Atlantic City, NJ, about being beaten and tortured for attempting to register to vote.(From a Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party filmstrip, made in winter 1964–1965, by the author and others, Tougaloo, Mississippi. Notes for a script to accompany it are found here: http://cdm15932.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15932coll2/id/25907 , Mary E. King Collection, Wisconsin State Historical Society.)Mrs. Hamer was philosophical and searched for basic truths; she pondered the meaning of events. For example, she claimed, “I work for the liberation of all people, because when I liberate myself, I’m liberating other people” (Hamer, 1970, p. 610). She thought about the connections between colliding forces, about what her experience showed, as she deliberated and drew conclusions. “In the past, I don’t care how poor this white woman was, in the South she still felt she was more than us,” Mrs. Hamer observed. “In the North, I don’t care how poor or how rich this white woman has been, she still felt like she was more than us. But coming to the realization of the thing, her freedom is shackled in chains to mine, and she realizes for the first time that she is not free until I am free” (Hamer, 1970, p. 611). As Bernice Johnson Reagon phrased it, “Mrs. Hamer was and is timeless and relentless in her honesty. She insisted that the relationships between maids and nursemaids and their employers be a part of any discussion about sisterhood” (Reagon, 1990, p. 213). - eBook - PDF

- John Hollitz(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Though no Black Panther, Fannie Lou Hamer had been converted to the cause of Black Power even before Carmichael had coined the term. After the 1964 Democratic National Convention, she was thoroughly disillusioned with the white-dominated power structure. In 1966, she began to express support for Carmichael and speak at rallies that promoted black separatism. She was never able to go as far as Robert Moses, however, who declared that he would not have anything to do with white people again. Nor did she agree with SNCC when it decided in 1968 to kick whites out of the organization. Although she agreed with Black Power advocates about the need for black self-determination, she did not believe that separating themselves from whites was the best way for blacks to achieve a larger voice in government. African-American communities needed to control their own educational, economic, and political institutions. Appealing to whites in positions of power to help blacks did not work. [See Source 3.] For Hamer, Black Power was a practical guide for action in her own community. As the civil rights movement fragmented in the face of growing black militance, Hamer was promoting alternative institutions that would further black economic self-reliance. By 1965, she was devoting much of her energy to the Mississippi Freedom Labor Union (MFLU). A union of domestic workers, truck drivers, and laborers, the MFLU promoted black ownership of homes, businesses, and land before falling victim to internal squab-bling and shaky finances in 1966. Several years later, she helped found the Freedom Farm Cooperative to provide poor blacks and whites in Sunflower County with food and homes. The cooperative lasted for only five years, but during that time, it purchased nearly seven hundred acres and built seventy low-cost homes. 218 C H A P T E R 11 Copyright 2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. - eBook - ePub

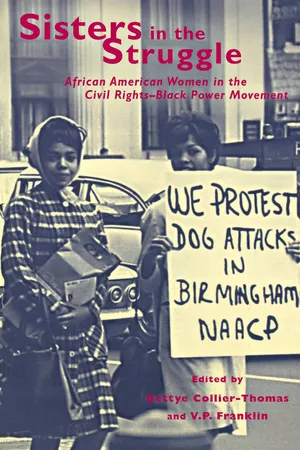

Sisters in the Struggle

African American Women in the Civil Rights-Black Power Movement

- Bettye Collier-Thomas, V.P. Franklin(Authors)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- NYU Press(Publisher)

Malcolm’s promise of protection assumes a stance of victimization on the part of those who need to be protected without allowing much room for their agency in other spheres. It places the woman in the hands of her protector—who may protect her, but who also may decide to further victimize her. In either case her well-being is entirely dependent on his will and authority. Note Malcolm’s words upon hearing the dynamic Fannie Lou Hamer speak of her experiences in Mississippi:When I listen to Mrs. Hamer, a black woman—could be my mother, my sister, my daughter—describe what they have done to her in Mississippi, I ask myself how in the world can we expect to be respected as men when we will allow something like that to be done to our women, and we do nothing about it? How can you and I be looked upon as men with black women being beaten and nothing being done about it? No, we don’t deserve to be recognized and respected as men as long as our women can be brutalized in the manner that this woman described, and nothing being done about it, but we sit around singing “We shall overcome.”6Later, when introducing her at the Audubon, Malcolm would refer to her as “the country’s number one freedom-fighting woman.” However, the predominant tone of this passage refers to Hamer only as victim in need of protection—not the protection afforded to citizens by their governments (which the South and the nation at large did not provide) but the protection of a black man. Hamer’s victimization makes black men the subject of Malcolm’s comment. When read closely, the above statement is not a paragraph about Fannie Lou Hamer but about the questionable masculinity of black men, particularly those black men of the southern Civil Rights Movement such as Martin Luther King. If black men protected “their” women, then Ms. Hamer would not be a victim of such abuse. Nor would she be a freedom fighter—that would be a position monopolized by black male protectors. - eBook - ePub

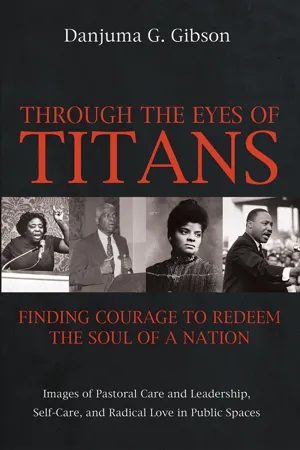

Through the Eyes of Titans: Finding Courage to Redeem the Soul of a Nation

Images of Pastoral Care and Leadership, Self-Care, and Radical Love in Public Spaces

- Danjuma G. Gibson(Author)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- Cascade Books(Publisher)

For Hamer, the connection between a praxis of love and education, the health of the democracy, and justice and equality represented an inter-locking and reciprocating interchange that was self-evident and irreducible. That is to say, you cannot have one without the other. Perhaps in her most damning critique of a racialized America, Hamer uses the praxis of love to challenge the normalization of racial hatred, arguing that if equal rights meant internalizing and adopting (as that which is morally right) the values of a racist power structure, then she will not aspire to any such equivalency. It is clear then that when she uses the phrase “white America,” she is not referring to people of European descent, but those who adhere to the social construct of white American supremacy. While current scholarship understands this centuries-old binary as racism vs. anti-racism, for Hamer, it is love vs. hate:But what I’m trying to say to you tonight, we are faced with some difficult days ahead. And I hope white America learns to love, before they teach every one of us to hate . This is what is happening in this country. And you see I couldn’t tell anybody in my right mind that I am fighting for equal rights because I don’t want any. I am fighting for human rights, because I don’t want to be equal to the people that rape my ancestors, dead, kill out the Indians, dead, destroyed my dignity, and taken my name.178This chapter is not a biographical interpretation of Fannie Lou Hamer. There has been significant and commendable scholarship done in this area.179 The goal here is to profile a salient psychospiritual practice embodied by Hamer that lends itself to redeeming the soul of the nation. In this case, that psychospiritual practice is the ethic of love—emphasizing what a praxis of love entails. We know what violence looks like. But as a matter of both pastoral theology and practical theology, the fundamental question remains, how do we know love when we see it? I suggest we see the praxis of love embodied in the life of Hamer. Perhaps one of the pivotal moments in the life of Fannie Lou Hamer was the unimaginable evil she suffered at the hands of prison officials and other inmates at the Winona, Mississippi, jail on June 9 , 1963 . Having traveled throughout Mississippi to encourage black people to vote, Hamer and her colleagues were arrested when their bus arrived at Staley’s Café in Winona. The beating that Hamer endured at the jail was nothing short of savage. Her testimony at a federal trial (on December 2 , 1 963

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.