History

Cesar Chavez

Cesar Chavez was a prominent American labor leader and civil rights activist who co-founded the National Farm Workers Association, later known as the United Farm Workers (UFW). He dedicated his life to advocating for the rights of farm workers, leading nonviolent protests and boycotts to improve their working conditions and wages. Chavez's efforts significantly contributed to the advancement of labor rights and social justice in the United States.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Cesar Chavez"

- eBook - ePub

- Desirée A. Martín(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Rutgers University Press(Publisher)

3 Canonizing César Chávez Throughout his nearly forty years of labor and civil rights organizing, César Estrada Chávez, the co-founder of the United Farm Workers Union (UFW), civil rights leader, and Chicano icon, drew upon various modes of official and popular spirituality, investing his political project with a sense of justice rooted in religious morality and an aura of sacrifice. His spiritual practices included his famous fasts, pilgrimages, and prayer vigils, but they also encompass nonviolence, peaceful boycotts, vows of poverty, and the use of religious imagery such as the Virgin of Guadalupe (Griswold del Castillo and García 36). 1 Chávez is certainly a political, social, and cultural hero for Chicanos/as and other marginalized groups in the United States and elsewhere. When he founded the UFW in 1962, in “the long organizing journey that was to be called La Causa,” he “concomitantly inspired the Chicano political movement and largely occasioned its attendant cultural renaissance” (Levy “Prologue,” n.p.; León, “Chavez” 857). Indeed, Gloria Anzaldúa links Chávez to the actualization of Chicanos/as in the United States: “Chicanos did not know we were a people until 1965 when César Chávez and the farmworkers united” (85). He remains the most well-known Chicano public figure in history. 2 Yet he is not solely a political or cultural leader, for he is frequently mythologized as a sacred figure that at first glance appears to evoke a more conventional notion of saintliness than many popular saints. Though he does not have a traditional religious cult, Chávez is akin to a popular saint; as Stephen R. Lloyd-Moffett asserts, “Five hundred years ago, this man would be seen as a living saint. . .. Once his actions are read through the prism of his religious life, Chávez emerges as a classical Catholic saint whose closeness to God led him to be seen as a Prophet by his people” (106–107) - eBook - PDF

American Voices

An Encyclopedia of Contemporary Orators

- Bernard K. Duffy, Richard Leeman, Bernard K. Duffy, Richard Leeman(Authors)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

The Chavez children had few opportunities for an adequate formal education, but young Cesar's informal education taught him much that would be indispensable in later years. Various CESAR ESTBADA CHAVEZ (1927-1993) Labor Leader and Civil Rights Activist JOHN C. HAMMERBACK AND RICHARD J. JENSEN 62 Cesar Estrada Chavez (1927-1993) family members spoke out against growers who mistreated their workers, provided personal aid and support to workers, and joined associations and unions of workers—organizations neither permanent nor successful until decades later, when Cesar made his indelible mark on labor history. From his early experiences, Chavez learned many important lessons—including the value of assertively confronting injustice, the mistakes to avoid when attempting to organize agricultural workers, and the ways of farmwork- ers and migrant workers. After a variety of uninspiring and dead-end jobs, Chavez served in the Navy in World War II and married. Lacking focus in his life, he drifted into San Jose, California, and settled in a barrio called "Sal Si Puedes," an expression that translates roughly as "escape if you can." In the 1950s his apparently ordinary life began its transformation into the extraordinary when he discovered his purpose for being. Direction came from Father Donald McDonnell and Fred Ross, his two mentors in life as well as in labor organizing. Father McDonnell taught Chavez about social justice and the history of labor movements among farmworkers, and tutored him regarding the Roman Catholic Church's teachings on the need for supporting workers and promoting moral causes. Fred Ross, a long- time activist and organizer, enlisted Chavez in the Community Services Organization (CSO), a community organizing group for Mexican Americans that was sponsored by Saul Alin- sky's Chicago-based Industrial Areas Founda- tion. While rising to a leadership position in the CSO, Chavez grew increasingly frustrated that the group would not organize farmworkers. - No longer available |Learn more

- José-Antonio Orosco(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- UNM Press(Publisher)

Chavez himself resisted the idea of being an ethnic leader during his lifetime. Some people today are hesitant to refer to Chavez as a Chicano, despite his obvious inspiration to the Chicano civil rights movement or Movimiento. It is also likely that a large number of recent Latino/a immigrants are unfamiliar with the farmworker history forged by Chavez over forty years ago. This beer commercial, then, might reveal more about its creators than it does about the intended Latino/a audience. It is as if the political imagination of mainstream America requires an icon, a leading figure that acts like a placeholder to embody the needs, interests, and complexities of an entire ethnic group. Indeed, some political commentators of the immigrant justice demonstrations in 2006 noted, almost in awe, that there were no major leaders or spokespersons on the level of a Cesar Chavez or Martin Luther King Jr. to coordinate and manage them. 1 Yet, as Robert Suro of the Pew Hispanic Center maintains, it is unlikely that even a figure such as Cesar Chavez could unite the over forty million Latinos/as in this country in any sort of political coalition, diverse as this group is in its values and ideas. 2 People working in Martin Luther King Jr. scholarship have long argued over whether it is appropriate to elevate King as the lone icon or figurehead for the civil rights movement of the 1960s. For some, this approach is objectionable not only because it ignores the everyday contributions to racial justice of hundreds of nameless and faceless activists but because it also turns King into a charismatic and saintly hero who single-handedly shifted the course of American history. The danger of such exaltation is that it further removes King from the lives of ordinary people who feel they cannot relate to or compare with someone with such talent and ability - eBook - ePub

Brown Church

Five Centuries of Latina/o Social Justice, Theology, and Identity

- Robert Chao Romero(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- IVP Academic(Publisher)

The Spiritual Praxis of César ChávezC ÉSAR CHÁVEZ WAS the preeminent leader, voice, and public face of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.1 Chávez is to Latinas/os what Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is to the African American community. Moreover, as the posthumous recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Aztec Eagle,2 and a US postage stamp in his honor, Chávez has been called the world’s most famous Latino.3 Together with Dolores Huerta and Filipino organizers Larry Itliong and Philip Vera Cruz, Chávez founded the United Farmworkers of America (UFW).4 The UFW fought for increased wages and better working conditions for exploited California farmworkers and rose to national attention through the famous Delano grape strike and international boycotts of 1965–1970.Although César Chávez is revered as the most highly regarded Latina/o civil rights icon of the 1960s, his critical role as faith-rooted activist of the Brown Church has been largely overlooked. Most scholars of Chicana/o studies, as well as activists, have ignored the centrality of Christian spirituality in his personal life and the broader farm workers movement. In the words of Chávez, “Today I don’t think I could base my will to struggle on cold economics or on some political doctrine. I don’t think there would be enough to sustain me. For me, the base must be faith.”5This chapter explores the spiritual formation and praxis of famed Chicano civil rights leader César Chávez during the famous grape strike of 1965–1970, and highlights his role as the most famous twentieth century community organizer and activist of the Brown Church. Methodologically, it draws from the broad—and disparate—secondary literature on the life of Chávez. Some of this literature explicitly highlights the Christian spirituality of Chávez;6 most of it hints at the profound role of faith in his upbringing and praxis, but does not offer explicit analysis of religion in the farmworkers movement.7 In addition to synthesizing the existing secondary literature, this essay is also based on a systematic review of Chávez’s own words about faith as expressed in his autobiography.8 - eBook - PDF

- Ilan Stavans(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

César was multifaceted; he wasn’t just one thing, even though people identified him with farm labor. Thus, for Felix, César was more than a leader of farm workers; he influenced goals and policies in other arenas. While working with the union [His leadership] touched many other points of the spectrum . . . he went from a leader to a great leader . . . I think César even surpassed being a great leader because he became a leader who went beyond his immediate group. He reached a status of international focus. From Alvarez’s perspective, Chávez was internationally recognized as a man of peace and a humanist concerned with the welfare of those who work for their sustenance. For Alvarez and other leaders, Chávez was an accurate representation of the farm working person he struggled to defend. For example, Alvarez observed, Chávez did not expend much energy promoting his particu- lar ethnic identification, yet he was able to represent his ethnicity in the ways he carried himself and in his actions with and for his people. Alvarez continued, A Catalyst for Change 99 his identity as a Chicano, being Mexicano, being Indio, or being part of the an- cestry of the people from here was clear, even though he didn’t go around bang- ing that drum. He didn’t have to tell you that he was brown; he was brown. He didn’t have to tell you that he thought in Indian ways because he acted in an Indian way. Clearly Alvarez did not perceive Chávez as a monotypic leader who professed merely to have the influence and authority of a union president. In Alvarez’s reflections on the man as a leader, Chávez did not autocratically dictate the direction of his movement, but guided it using humility, commitment to change, and investment in the workers whom Chávez considered the most dispossessed of our society. As Alvarez saw it, Chávez directly and indirectly influenced many by his life, his vision, and his actions. - eBook - ePub

The Farm Labor Problem

A Global Perspective

- J. Edward Taylor, Diane Charlton(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Chapter 7Farm Labor Organizing From Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers to Fair Foods

Abstract

Most farm workers around the world are poor and vulnerable, with little education and few alternatives to doing hired farm work. In the United States, Cesar Chavez and the United Farmworkers Union faced the challenge of organizing a workforce that was seasonal and mostly immigrant, without legal status. Farm labor advocacy is more daunting in an era of complex, global food supply chains. This chapter uses economic tools to analyze the successes and failures of farm labor organizing as well as new strategies that leverage the food supply chain in an effort to improve agricultural working conditions in rich and poor countries.Keywords

Farm labor unions; Cesar Chavez; United Farm Workers; Labor strikes; Consumer boycotts; Fair Foods ProgramIt's ironic that those who till the soil, cultivate and harvest the fruits, vegetables, and other foods that fill your tables with abundance have nothing left for themselves. Cesar ChavezHuman slavery is a not a thing of the past, but an ugly crime that still continues to afflict our communities. A. Brian Albritton, US Attorney for the Middle District of FloridaMost farm workers around the world are poor and vulnerable, with little education and few alternatives to doing hired farm work. In the United States, Cesar Chavez and the United Farmworkers Union faced the challenge of organizing a workforce that was seasonal and mostly immigrant, without legal status. Farm labor advocacy is more daunting in an era of complex, global food supply chains. This chapter uses economic tools to analyze the successes and failures of farm labor organizing as well as new strategies that leverage the food supply chain in an effort to improve agricultural working conditions in rich and poor countries. - eBook - ePub

Can I Get a Witness?

Thirteen Peacemakers, Community-Builders, and Agitators for Faith and Justice

- Charles Marsh, Shea Tuttle, Daniel P. Rhodes, Charles Marsh, Shea Tuttle, Daniel P. Rhodes(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Eerdmans(Publisher)

ESAR CHAVEZ(1927–1993)Cesar Chavez portrait, Forty Acres Headquarters, Delano, CA, 1969. Photo: Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.Passage contains an image

IN THE UNION OF THE SPIRITCesar Chavez and the Quest for Farmworker Justice Daniel P. RhodesTo all appearances, Cesar Estrada Chavez was a rather unimpressive figure. Diminutive in stature, he had a boyish face, a wide, faintly aquiline nose, chestnut skin, and thick onyx-colored hair often neatly parted low on the left side and combed back and to the right across his head. He was handsome but forgettable. That he would organize the first farmworker union in a struggle for justice that took on the industry of agribusiness scarcely seemed possible.The differences could not be starker between Chavez and the heroes of popular Westerns playing during the time that he was organizing farmworkers in southern and central California. Next to a Roy Rogers or a John Wayne, he surely would have seemed unintimidating and even unremarkable. Compared to the great orators of the day—such as Malcolm X or Martin Luther King Jr.—he would have seemed prosaic. Only his eyes offered a clue: they were captivating and intense. He was hobbled by chronic back pain much of his life as a result of years spent working bent over in the fields, bone depletion, and one of his legs being slightly longer than the other, something that would be diagnosed later in his life. Yet this physical fragility and meekness was nearly eclipsed by the calm, fortified nature of his presence. One journalist biographer described him as a person of “density” who “walks as lightly as a fox.”1 He had a sharp sense of humor, and though he was kind, he could also be acerbic. As a kid he had been a travieso (prankster), and this disposition served him well throughout his life.2 - eBook - PDF

The Self-Help Myth

How Philanthropy Fails to Alleviate Poverty

- Erica Kohl-Arenas(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

37 On March 10, 1968, in the Central Valley town of Delano, a weak Cesar Chavez, held up by two elder farmworkers in faded som-breros, walks slowly through crowds of supporters waving black-and-red flags. With the word huelga (strike) boldly emblazoned above an Aztec eagle, the flag inspires dignity among the Chi-cano people and hope for change on behalf of the state’s agricul-tural field workers. Flanked by his mother and Robert F. Kennedy—and under the watchful eyes of Dolores Huerta and his wife Helen—Chavez feebly sits to receive a morsel of bread from a Catholic priest. The priest speaks: “And he took bread in his hands, blessed it, and gave it to his disciples saying, ‘Eat all of it. For this is my body, the body of Christ. Amen.’” On this day, Cesar Chavez emerges from a twenty-five-day fast to call for nonviolence during one of the most heated moments on the picket lines of the historic California farmworker movement. This scene comes from the 2014 film, Cesar Chavez, directed by Mexican actor Diego Luna and performed by Latino Hollywood chapter two The Hustling Arm of the Union Nonprofit Institutionalization and the Compromises of Cesar Chavez 38 / Chapter Two stars. The film’s release, nearly fifty years after the Delano grape strike that launched the movement, follows the publication of several new books that complicate a story most commonly told, as in the film, through the singular heroic efforts of Cesar Chavez. In Trampling Out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers , Frank Bardacke, a former antiwar student activist who became a seasonal farmworker, reveals the success and the undoing of the movement through the tensions between its “two souls.” 1 The first soul was the union built by fieldworkers and an army of volunteers fighting growers through organizing, strikes, and public actions across California’s Central Valley. - eBook - PDF

Refugees Now

Rethinking Borders, Hospitality, and Citizenship

- Kelly Oliver, Lisa M. Madura, Sabeen Ahmed, Kelly Oliver, Lisa M. Madura, Sabeen Ahmed(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Rowman & Littlefield Publishers(Publisher)

A rights claim may have immediacy and most pressing ur-gency with respect to legal coevals, but it always puts us in distinct legal and moral responsibilities with past and future generations. The Rights of Immigrants and the Duties of Nations 195 Cesar Chavez: WITNESS OF PEACE AND PENITENT OF JUSTICE Cesar Chavez’s activism and labor organizing, spanning as it did four de-cades, also became the historical register, the social archive, of the transfor-mation that activism underwent in the United States. Chavez, like Martin Lu-ther King Jr. and Malcom X, appealed to an anticolonial language that gave urgency to his struggle that made it command the attention of the American public. Undoubtedly, Chavez’s success and the efficacy of La Causa were due to the fact that King, inspired by Gandhi, had made the language of non-violence the vernacular of U.S. social and political movements during this decisive period in American history. At the same time, Chavez’s appeal and success also had to do with the stark way in which he articulated an agenda of social transformation that rejected the language of violence and polarization that we saw in the Black Panthers, the Brown Berets, and the Weather Un-derground. Along with King’s language of civil disobedience, nonviolence, and Christian agape, Chavez also brought in the Black Pride movement’s language of autonomy, self-determination, self-reliance, and cultural pride. La Causa was as much about transforming conditions of exploitation and injustice as it was about affirming the cultural pride, political autonomy, and will to self-sufficiency of farmworkers. Like Martin Luther King Jr., Chavez also drew on the symbolic and moral reservoir of his religion to fashion a distinctive message that resonated with the U.S. moral and religious identity. Chavez drew on his deep popular Catholicism but also on the Mexican American and Latino communities’ Catholic sensibilities. - eBook - PDF

- Gary L. Anderson, Kathryn G. Herr, Gary Anderson, Kathryn G. Herr(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications, Inc(Publisher)

He was one of the founders of the Mexican American Youth Organization and a leader among students in the movement. Distraught over the blatant racism in Crystal City, he participated in a citizens’ organizing committee and vowed to take control of the school board at the 1970 election. Out of this group’s action came the La Raza Unida Party (LRUP), an alternative political party for Chicanos/as. At the local level, LRUP garnered 15 city officials, including 2 mayors, 2 school board majorities, and 2 city council majorities; this was the first of its kind in the Winter Garden area of Texas. However, the party was short-lived. Splits between the leadership, insufficient funds, the absence of an attractive platform, and limited membership denied the party of any signif-icant growth. Most prominent of all other leaders, César Chávez arguably led the fight in a two-prong offensive. Chávez played the roles of civil rights leader and labor leader. In 1965, Filipino farm workers, under the lead-ership of Larry Itliong, Pete Velasco, Philip Vera Cruz, and others, struck in the grape fields of Delano, California, demanding union recognition, as well as better wages and working conditions in an industry that exploited its workers. In a strategic move, Filipinos in the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) joined with the National Farm Workers Association and their leader, César Chávez. 312 ——— Chicano Movement Once they joined forces, the farmworkers movement took off full force, propelling César Chávez into worldwide recognition. The Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee and National Farm Workers Association merged to become the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, which later became the United Farm Workers. - eBook - PDF

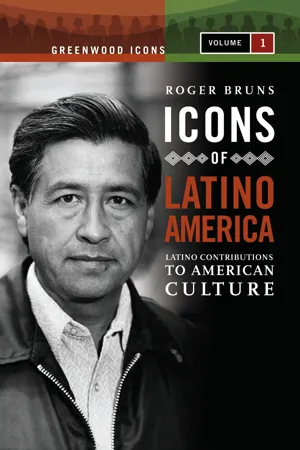

Icons of Latino America

Latino Contributions to American Culture [2 volumes]

- Roger Bruns(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

They decided to ask Chavez, Huerta, and the other leaders of the Farm Workers Association to help in the strike. On September 16, 1965, the members of the union gathered at a church in Delano. Local disc jockeys on Spanish radio announced that an impor- tant decision would soon be announced. Chavez explained to the member- ship what a strike would entail. He knew in his heart how the members would respond. Around 500 workers and their leaders, voted unanimously to join the strike. From the church, the cry sounded: Viva la huelga! (Long live the strike!) From the outset of the strike, Chavez preached the message of nonvio- lence. He had seen Martin Luther King, Jr., and other black civil rights lead- ers use the tactic successfully. Like King, Chavez was deeply religious. The union often held religious services, and Chavez surrounded himself with Christian leaders from various denominations. One minister who joined the strike said, ‘‘I’m here because this is a movement by the poor people them- selves to improve their position, and where the poor people are, Christ should be and is.’’ 11 Like Martin Luther King, Jr., Chavez also read and deeply respected the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi. Indeed, it would be Chavez himself who would use the fast, as Gandhi had in India, to attempt to motivate social change. Striking workers began to march in front of the vineyards where growers wanted them to work for miserly wages. Huerta, who seemed born for such clashes, coordinated the picket lines, entreating those who grew tired to keep up the pressure. She was tough-minded, focused, and, in the eyes of many, indefatigable. In the Delano strike, Huerta would join workers in jail for violating local ordinances and orders from police. It would be the first of more than twenty arrests over the course of her career. She would see the arrests as badges of honor. 272 Latino Contributions to American Culture

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.