History

Freedom Summer

Freedom Summer refers to a 1964 voter registration drive in Mississippi, organized by civil rights organizations to increase African American voter participation and challenge segregation. The campaign aimed to confront racial discrimination and empower African Americans to exercise their right to vote. Despite facing violent opposition, the initiative significantly contributed to the Civil Rights Movement and the eventual passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Freedom Summer"

- eBook - PDF

- Thomas S. Poetter(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Information Age Publishing(Publisher)

Freedom Summer: A PEDAGOGY OF POLITICS AND HOPE Freedom Summer needs to be understood against the context of the larger Civil Rights Movement. The Movement is largely assumed to have begun in the mid-1950s with the Brown decision and with the Montgomery bus boycotts. The purpose of the Movement, of course, was to initiate change to destroy legally supported segregation and racism across social and polit-ical institutions. By the early 1960s, the Movement received focused national attention due to the efforts of the Student Nonviolent Coordinat-ing Committee (SNCC), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), the NAACP, and count-less other groups and individuals working and sacrificing for racial justice. Although in many ways Freedom Summer was the nexus of the civil rights movement, the fact is that Southern Blacks had been organizing and work-ing on their own behalf for years. “[I]n many instances, however, SNCC staffers were the first paid civil rights workers to base themselves in isolated rural communities, daring to ‘take the message of freedom into areas where the bigger civil-rights organizations fear to tread’” (Bond, in Martinez, 2002, p. v). SNCC, which had been founded in 1960 during the sit-in move-ment, sought to change the political order of the South and was among the first organizations to press for Black voter registration and the creation of independent political parties. The organization realized that in order for 202 K. M. TALBERT Black citizens to have the full fruits of their citizenship, and for legal changes to become reality, enfranchisement was essential. The SNCC volunteer Robert Moses initiated the first plans for a statewide voter-registration campaign in Mississippi in 1961. “The state of Mississippi became a laboratory for SNCC’s unique methods of organizing” (Bond, in Martinez, 2002, pp. vii–viii). - eBook - ePub

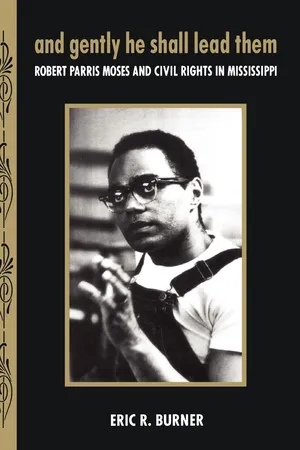

And Gently He Shall Lead Them

Robert Parris Moses and Civil Rights in Mississippi

- Eric Burner(Author)

- 1994(Publication Date)

- NYU Press(Publisher)

SEVENFreedom Summer

The Freedom Vote in the fall of 1963 was one victory for Robert Moses and his co-workers. The movement needed whatever victories it could get. Registration of blacks by mid-1963 was about three percent of all voters in the state; of all eligible blacks, only six percent were registered.1 The state was intransigent, the federal presence negligible. Nationally visible figures like Martin Luther King were not at the Mississippi battlefront to lend voice and publicity. “It was clear,” Moses has remarked, “that the NAACP and SCLC and CORE, none of them were really willing to put a major drive into Mississippi.… They called for working in other parts of the South first.… And NAACP’s whole policy was work all around the state.”2 SNCC’s customary methods were not cracking Mississippi. In November 1963 VEP director Wiley Branton had cut off funds to COFO’s operation in Mississippi, announcing that the organization would continue to offer minimal support for the Greenwood office from December through March and explaining that the funds already allocated to Mississippi exceeded those given to any other state. In a letter sent jointly to Henry and Moses, he added: “Of almost equal importance to our decision is the fact that the Justice Department has failed to get any meaningful decrees from any of the voter registration suits which have been filed.… We are also very concerned about the failure of the federal government to protect the people who have sought to register and vote or who are working actively in getting others to register.”3 - eBook - ePub

The Mississippi Civil Rights Movement and the Kennedy Administration, 1960-1964

A History in Documents

- James P. Marshall(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- LSU Press(Publisher)

View Freedom on My Mind (see chapter 2, document 6 source, above, for full reference) and Freedom 50 (nine DVDs) by Veterans of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement, Inc., 2015. See also Visser-Maessen, Robert Parris Moses, 169–75 and 180–85, concerning the debate on whether to have the Summer Project and the importance of Louis Allen’s murder in making the decision to go forward with it. See Watkins, Brother Hollis, 221–27, for the debate within COFO on whether to have large numbers of whites in the Summer Project, as well as a growing surge of Klan violence in the state. See Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Cambridge, MA, 1981), 96–129, and Bruce Watson, Freedom Summer: The Savage Season That Made Mississippi Burn and Made America a Democracy (New York, 2010). See also Marshall, Student Activism, 81–82, on whether to involve large numbers of whites in the Summer Project. Document 1 is selected sections of the COFO (Council of Federated Organizations) Handbook for Political Programs which was used to orientate the Summer Project volunteers. The handbook is composed in part of the following sections: Historical Background, SNCC Enters State, Civil Rights Act Employed, Summer Project Plans, and Voter Registration Summer Prospects. This handbook was used in 1964 and parenthetically again in North Carolina in 2013 when Jim Marshall supplied it to Bob Zellner, who used it to train young North Carolinians in voter-registration work. 1. COFO Mississippi: Handbook for Political Programs INTRODUCTION Historical Background In 1876 Rutherford B. Hayes, newly elected President of the United States, ordered the withdrawal of Federal troops from the South. That order, for all practical purposes, marked the end of Negro participation in Mississippi government. . . - eBook - ePub

The Civil Rights Movement

A Documentary Reader

- John A. Kirk(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Chapter 8 The Civil Rights Act of 1964, Freedom Summer, and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, 19648.1 US Congress, Civil Rights Act of 1964

President Lyndon B. Johnson was well equipped to take forward the civil rights legislation that Kennedy had proposed. As a Texan, Johnson was considered a southerner, but he was also someone who was sympathetic to civil rights. An admirer of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal liberalism, Johnson gained first‐hand experience of racial and ethnic discrimination while teaching in segregated Mexican‐American schools. Unlike the younger and fresh‐faced Kennedy, Johnson was a seasoned politician, having served as a US congressman, senator, senate majority whip, and senate Democratic leader. This gave Johnson the necessary political experience and connections to drive civil rights legislation through a normally recalcitrant Congress that was full of powerful southern politicians. The signing into law of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 on 2 July also reflected in no small measure Johnson’s political skill in casting the legislation as a tribute to a slain President Kennedy for a nation still in mourning. Of course, the legislation equally rested on the moral force of movement activists’ demands at local, state, and national levels, and the movement’s successful building of a national public consensus outside of the South in support of civil rights.The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a very wide‐ranging piece of legislation. Title I tackled voting rights, although not nearly comprehensively enough, which led to separate and more extensive legislation the following year. Title II prohibited discrimination in public accommodations on the basis of “race, color, religion or national origin.” Title III prohibited state and local government from denying access to public facilities. Title IV paved the way for a more rigorous enforcement of school desegregation. Title V expanded the role of the Civil Rights Commission, which had been formed by the Civil Rights Act of 1957. Title VI prevented discrimination by government agencies in receipt of federal funds. Title VII tackled employment discrimination, including discrimination against women in the workplace. Title VIII required the compilation of voter registration and other voting data in certain geographical areas. Title IX made it easier to move civil rights cases from state to federal courts. Title X established a Community Relations Service to assist in community disputes involving racial discrimination. Title XI dealt with how charges against those in violation of the act were handled. - eBook - ePub

I Am a Man!

Race, Manhood, and the Civil Rights Movement

- Steve Estes(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- The University of North Carolina Press(Publisher)

In the spring of 1964, SNCC leaders assessed the lessons of the campaign. The white Democratic candidate, Paul Johnson, had won, but according to SNCC organizer Ivanhoe Donaldson, this was almost beside the point. The freedom vote “showed the Negro population that politics is not just ‘white folks’ business,’” Donaldson observed, and also that “whites can work [for civil rights] in Mississippi (at least white males).” Recognizing the important contributions of volunteers, Donaldson and others in SNCC still feared that given southern taboos against “miscegenation,” the presence of white females would add a volatile ingredient to an already explosive situation in Mississippi. These and other concerns about the volunteers set the stage for a debate over the role of white students in the Mississippi summer project of 1964. 19 In the wake of the freedom vote, SNCC'S small cadre of Mississippi organizers began to plan a much larger campaign for the summer. SNCC then teamed up with the NAACP and other civil rights groups in an alliance called the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO). As the strongest proponents of the summer project, SNCC'S Bob Moses and Charlie Cobb argued that student volunteers could staff a massive voter registration campaign and teach summer classes for the state's black children, who attended substandard, segregated schools during the year. Many local organizers, however, worried that the volunteers’ educational advantages would overwhelm and intimidate local activists - eBook - PDF

The Racial Divide in American Medicine

Black Physicians and the Struggle for Justice in Health Care

- Richard D. deShazo(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- University Press of Mississippi(Publisher)

2 They stayed in the city’s finest hotels and were treated with the utmost respect by city officials and by the Jackson police. A half century ago they had come to Mississippi as volunteers in what would later be called Freedom Summer, invited by civil rights leaders to work on voter registration campaigns, staff community centers, and teach in the new Freedom Schools. Nonthreatening stuff, one would think. But for many white Mississippians, the influx of hundreds of “outside agitators” constituted an invasion that had to be repelled. Freedom Summer, Mississippi Burning, and Jack Geiger’s Dream 107 Summer 1964 During its 1964 spring session, the Mississippi legislature had passed a series of laws banning picketing and leafleting, while doubling the number of state police. In Jackson, Mayor Allan Thompson beefed up his force, bought two hundred shotguns and ordered fifty more, converted two city trucks into troop carriers, and purchased a combat vehicle—“Thompson’s Tank”—that carried ten officers and two drivers, with shotguns protruding from gun ports. Rumors spread like wildfire. Some whites were convinced of the rumor that black men sporting white bandages around their necks had been designated to rape white women. Sales of guns, ammunition, and Klan memberships boomed. In McComb, upstanding citizens formed HELP, Inc., a self-defense group organized in a white middle-class neighborhood. Members set up an alarm system to warn of an imminent attack by the civil rights workers. HELP guidelines warned citizens to “keep inside during darkness or during periods of threats. - eBook - ePub

- AAVV(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Publicacions de la Universitat de València(Publisher)

The symbolic field of the text connects two places with seemingly distinct histories, and on more than one temporal plane: facing northward, a chain of syntagmatic images links the archipelago to the continental US; facing southward, the metaphors that emphasise that connection are fragile, and made more tenuous by an overarching nationalism, but in the novel they emerge as metaphysical and natural: the sea, and the storms and hurricanes that unite sites of pain and loss in the Caribbean and the U.S. South. Whether another person’s point of view is listened to, or understood, is made crucial, both at the personal level of Sara and Sam’s relationship and in terms of historical common ground and political interdependence. In my reading, the novel takes the shape of a series of questions about the movement not all of which are answered. Those that are answered find their resolution in the social symbolic, notably: To what extent may the convergence of race and rights in Mississippi in 1964 act as a fulcrum for respecting a broader history forged across seemingly ex-centric and exotopic places i.e. the former plantation regions of the Caribbean as well as the U.S. South, or “Plantation America” in George Handley’s conceptualization? And: To what extent could movement activists in the South conceive of racial justice outside of local and national models in the mid-1960s?The center of the novel is the notorious abduction and murder of Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman by a posse of police and Klansmen. The murders that took place on a deserted Mississippi back road in the dark of night of June 21, 1964 are relocated in a racial continuum and the recovery of the young men’s bodies is infused with a mystical hyperreality and Africanist moral force. Schwerner and Goodman were white volunteers from New York City and Chaney was African American and local to Philadelphia, Mississippi where they were all killed. The Freedom Summer Project that brought them together was designed to “take Mississippi to the nation” (Rev. Ed King, qtd. in Marsh 29). SNCC volunteer Fannie Lou Hamer, the granddaughter of slaves and one of twenty children in a sharecropper family, described the hope behind the COFO project: “They want to make democracy a reality in the whole country—if it is not already too late” (Hamer viii-ix). The national-symbolic importance of Freedom Summer far outweighed the relatively small number of participants; some 700 student volunteers joined COFO organizers in SNCC and the Council for Racial Equality (CORE), whose efforts to forge voter registration and community projects, including Freedom Schools, were buttressed by lawyers, ministers and doctors. Other activists lost their lives in 1964 but the murders of these three young men held the front page and also led to the first successful federal prosecution of a civil rights case in 1960s Mississippi. That the murders occurred at the very beginning of the campaign cast them in a luridly notorious light; while Chaney was a seasoned agitator with CORE and Schwerner something of a veteran working full-time with his wife Rita in Mississippi, Andrew Goodman was the representative student volunteer and his abduction within two days of arriving in Mississippi hit full force.4 The search for the bodies of the slain workers was one of the biggest undertaken by the FBI, with naval officers detailed to explore rivers, swamps and forests. That search is re-imagined in Beyond the Limbo Silence - eBook - ePub

We Will Shoot Back

Armed Resistance in the Mississippi Freedom Movement

- Akinyele Omowale Umoja(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- NYU Press(Publisher)

The events leading up to Freedom Summer reveal serious differences in the Movement around the role of nonviolence and the use of weapons. Certainly, though, SNCC and CORE members in Mississippi were becoming more receptive to, and in some cases participants in, armed self-defense. At the same time nonviolence was becoming less popular within the ranks of the southern Black Freedom Struggle. These trends would be strengthened by the occurrences of the summer of 1964.Freedom Summer

In spite of the abduction and murders of Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman, as well as the threat of violence by Mississippi segregationists, the Mississippi Summer Project went on as planned. Over three thousand students were recruited to volunteer in local COFO projects in thirty-eight communities. In each of these communities, COFO attempted to revitalize its voter registration efforts. In twenty-three Mississippi localities, community centers were constructed and organized. Also as a result of the Mississippi Summer Project, freedom schools that taught Black history, Movement politics, as well as literacy and math skills to Mississippi youth were organized in thirty communities in the state.44As predicted by Moses and Dennis, the massive involvement of White students in COFO projects did put Mississippi in the national media spotlight and, particularly after the abduction of the three COFO activists in Neshoba County, increased the presence of federal law enforcement. In spite of the increased FBI presence in the state and national media attention, White supremacists continued their campaign of violent terror on Mississippi communities and activists. Between June and October 1964, over one thousand activists and Movement supporters had been arrested by Mississippi police, thirty-seven churches bombed or burned to the ground, and fifteen people murdered due to the segregationist offensive of violent terror.45 - eBook - ePub

Joe T. Patterson and the White South's Dilemma

Evolving Resistance to Black Advancement

- Robert E. Luckett Jr.(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- University Press of Mississippi(Publisher)

CHAPTER 8Freedom SummerWHEN JOE PATTERSON WON A THIRD TERM IN OFFICE IN 1963, THE CIVIL rights movement was far from over, and long days remained for Mississippi’s attorney general. To come were the political challenges of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP); Freedom Summer; the murders of Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, and James Chaney; the Civil Rights Act of 1964; the Voting Rights Act of 1965; James Meredith’s March Against Fear; and countless other events. During those years, Patterson refused to renounce segregation and took tough stands against the movement. He also shaped a burgeoning brand of conservatism in the South, learned at the feet of Pat Harrison, which rejected the explicit racism that had characterized the region’s history but was predicated on the implicit subjugation of African Americans.In the 1920s and 1930s, Harrison was the “other” Mississippi senator during the days of Theodore Bilbo and James K. Vardaman, the demagogic forerunners of Ross Barnett. In fact, Harrison defeated Vardaman to win office, and as the state’s junior US senator, Bilbo refused to support Harrison when he ran for Senate majority leader, causing Harrison to lose that position by one vote. Within that context, Harrison fashioned a rhetoric and action plan that attempted to avoid issues of race in order to garner power within and support from the federal government, especially as chairman of the Senate Finance Committee during the New Deal. Joe Patterson joined Harrison’s staff as his chief legislative aide in 1936, and much of his future ideology and public career was shaped by the Mississippi senator.As Freedom Summer approached in Mississippi during 1964, Patterson stood at the forefront of a political machine that helped transition southern Democrats, who recognized the waning influence of white die-in-the-ditch resistance, into modern-day Republicans, who leaned on rhetoric meant to sustain white political hegemony without being explicitly racist. That transition was so successful that many purveyors of conservative politics believed that a supposed postracial America had dawned after the election of Barack Obama in 2008. No sign illustrated the shift in politics away from the days of Ross Barnett’s racist virulence better than Paul Johnson’s inaugural address as governor of Mississippi. - eBook - PDF

For a Voice and the Vote

My Journey with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

- Lisa Anderson Todd(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- The University Press of Kentucky(Publisher)

116 FOR A VOICE AND THE VOTE Someone from the Summer Project or in our group knew an artist in Memphis and arranged for us to sleep at his house. After staying up to talk, we slept on the floor from 3:00 to 6:00. This artist’s place was the messiest house I’d ever been in, but I didn’t care. I was safe enough and excited, knowing I was going back to Mississippi. This summer I would not just be learning about the civil rights movement but had been quali- fied as a civil rights worker. Leaving Memphis was the time to worry as we crossed the state line right away and entered Mississippi. We were part of the invasion of sum- mer civil rights workers that had received a great deal of local and national publicity. Anyone who noticed us had to know that the four of us were part of the Summer Project: the timing of our travel, out-of-state plates, young, integrated travelers. The police might stop us anywhere for ques- tioning, harassment, beatings, or fines. They might arrest us and take us to jail for a traffic violation that had not occurred. The police would at least record a description of the car and its license plate for possible future targeting. In March of that year, the governor of the state had referred to the summer volunteers as “organized revolutionaries” out to substi- tute federal law enforcement authority for state authority. The state police were trained in riot-control techniques and given full power in civil dis- orders rather than restricted to traffic law enforcement. The state legisla- ture had given the governor power to send the state police into areas with authority over local law enforcement. The local press used derogatory words, calling us a “broken-down, motley bunch of atheists,” “malcon- tents,” and “wild-eyed left wing nuts” to encourage readers to oppose us and to deter black support of the voter registration activities Mississippi was so anxious to stop.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.