History

Booker T Washington

Booker T. Washington was a prominent African American educator, author, and leader in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was the founder of the Tuskegee Institute, a historically black college in Alabama, and advocated for vocational education and economic self-reliance for African Americans. Washington's approach to racial progress, known as the Atlanta Compromise, emphasized education and economic advancement over political agitation.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Booker T Washington"

- eBook - PDF

- Richard T. Schaefer(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications, Inc(Publisher)

WASHINGTON, BOOKER T. (1856–1915) Born into slavery at Hales Ford, Franklin County, near Roanoke, Virginia, on April 5, 1856, Booker Taliaferro Washington became the most influential Black in the United States in the late post–Civil War period. His practical focus on education and economic self-help as a means to later political gains became a paradigm for race relations that was sharply contested by other Black leaders, such as W. E. B. Du Bois. Their two contrast- ing approaches to Black political inclusion have contin- ued into the present. This entry looks at Washington’s philosophy and achievements along with how his contemporaries and later Black leaders viewed him. His Life Immediately after the Civil War, young Booker and his family migrated to West Virginia to work in the mines. Desiring an education, Washington walked to the Virginia coast and, in 1872, enrolled in the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, from which he graduated in 1876. The principal, General Samuel Chapman Armstrong, had developed a cur- riculum of agricultural and industrial training together with inculcation of Christian morality, all amenable to southern Whites. In this period, when Reconstruction was halted and southern White racism was growing and expressing itself violently, Washington accepted this approach, together with its implicit acceptance of Black disen- franchisement and cooperation with Whites. He later promoted a version of Black self-help, believing that Blacks would be more accepted in Southern commu- nities if they provided the services and products Whites needed. After considering the legal and ministerial profes- sions, Washington settled on education and taught at the Hampton Institute till 1881. That year, he accepted an appointment as the first president of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, in Tuskegee, Alabama. - eBook - ePub

- Gene Andrew Jarrett(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Booker T. Washington (1856–1915)

When Booker T. Washington gave his famous speech before the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta on September 18, 1895, he was immediately hailed as successor to Frederick Douglass, who coincidentally had passed away earlier that year. The principal and founder of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, Washington was the most innovative African American educator and successful politician of his time, and Tuskegee was the most famous African American institution in the United States. As the first African American to eat dinner with the President of the United States at the White House, Washingtonespoused the conservative rhetoric that, for African Americans, thrift, hard work, and social usefulness were more important than political agitation for racial equality. Founding the National Negro Business League in 1900, he won theadmiration and gratitude of African American entrepreneurs long excluded from predominantly white business organizations. Yet, as W.E.B. Du Bois had pointed out, Booker T. Washington’s “paradox” lay in his position as a servant of two opposing constituencies: recently emancipatedsouthern African Americans, andthe moneyed white establishment that sought their continued subjugation. Doomed to juggle the demands of these two constituencies, Washington struck compromises that were controversial, if not contentious, given the egalitarian promises of Reconstruction.Booker Taliafarro Washington was born a slave in southwestern Virginia five years before the Civil War. His mother was an enslaved woman named Jane Ferguson, who took her children to West Virginia to reunite with her husband, Washington Ferguson, after the war ended. Although his biological father was a white man, probably his mother’s master, Washington took his stepfather’s first name as his own. Raised in profound poverty, Washington worked in the salt furnaces and coal mines of West Virginia throughout his childhood, an education in physical toil that informed his future commitment to manual and industrial training. He attended school at night. In 1872, he walked 200 miles to the Hampton Institute in eastern Virginia in pursuit of further education. Founded under the auspices of the American Missionary Association to educate African Americans and Native Americans in the early days ofReconstruction, Hampton introduced Washington to Samuel Chapman Armstrong, a Union Army general who believed that industrial education provided the best preparation for ex-slaves entering the Gilded Age economy. At Hampton, with Armstrong as his mentor, Washington worked as a janitor to pay his room and board, and graduated with honors in 1875. - eBook - ePub

Booker T. Washington

A Life in American History

- Mark Christian(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- ABC-CLIO(Publisher)

Why Booker T. Washington MattersIt is curious to consider the legacy of an African American historical figure who has been so maligned, misunderstood, and misinterpreted since his passing on November 14, 1915. Booker T. Washington requires revision, revitalization, and restitution by the historical community because he has been judged and fossilized by many unfairly. This is not hyperbole because the author too came looking at the life of this man with a skeptical mind. Yet when delving into the time period, the milieu, his start in life, one comes away embarrassed of ever having harbored scholarly resentment toward a truly good hearted and well-meaning African American man who wanted only the best for his people.Washington possessed a number of salient attributes that require unpacking more profoundly and put into the context of his life and times. After all, his was “a life in American history” that will stand the test of time, the fact that his main autobiographical account is still in print more than six score years after its first publication is astounding in itself. Yet what riles the spirit as a biographer is the manner in which he has been fossilized—cemented into a caricature and simply associated with “accommodationist” and the architect of the “disenfranchisement” of the African American during his lifetime. This is both spurious and flawed, and it reminds one of the way Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was also characterized as a cardboard “I have a Dream” figure in American history. Washington, just like Dr. King, was multidimensional in character and a force for the practical advancement of African Americans in an insidiously racist and nefarious social and cultural environment.Booker T. Washington speaks to a large audience in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, in the early 1900s. (Library of Congress) - eBook - PDF

- William D. Wright(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

64 These were revolutionary objectives, by any definition. And most Black historians and other kinds of intellectuals remain ignorant of them, and a great deal else about Booker T.Washington that they should know about and that Black people today should know about. The time has come for Black historians to rethink the way they think about Washington. Historians who do not deal with evidence, or who are afraid to do so, or who do not feel it is necessary to do so, are individuals who have to rethink who they are and what they are doing. Booker T.Washington was the single most important person in Black history. It is time that Black historians became aware of that and conveyed this knowledge and understanding to Black people and other Americans. Page 69 Chapter 4 Black Women in Black and American History In 1986 a symposium was published entitled The State of AfroAmerican History. It contained presented papers of a conference that had been held, involving Black and white historians, on where Black history stood in American history writing. There was a discussion of various themes in Black history and also of some related subjects. Black slavery, the Black urban experience, and the Black community were themes, accompanied by related topics such as Black history textbooks, teaching Black history in colleges and universities, and trends in Black history writing. There was commentary on the papers presented that appeared in the published book. There was an understanding that Black history should be integrated into the larger American history. Thomas Holt said the following about that in the introduction to the book: Thus, AfroAmerican history becomes a window onto which the nation’s history, a vantage point from which to reexamine and rewrite that larger history. - eBook - ePub

The Art of the Possible

Booker T. Washington and Black Leadership in the United States, 1881-1925

- Kevern J. Verney(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Booker T. Washington and the Negro's Place in American Life (1956). If acknowledging that Washington's leadership could be criticized as overly conservative, these accounts ultimately justified his program as the best that was available given the repressive racial conditions that prevailed in the United States at the start of the twentieth century.A similar outlook prevailed in Bernard Weisberger's Booker T. Washington (1972). Weisberger also argued that Washington became more forthright in his criticisms of racial injustice in his speeches and writings during the last years of his life between 1911 and 1915. Hugh Hawkins (ed.), Booker T. Washington and his Critics (1974), provided a helpful collection of extracts from the writings of Washington's sympathizers and detractors, including the views of both his contemporaries and later historians. Readers were thus encouraged to make up their own minds as to Washington's place in history.In recent years Louis Harlan has dominated the historiography on Booker T. Washington. In addition to editing the Booker T. Washington Papers, Harlan wrote a two-volume biography of the Tuskegeean, Booker T. Washington: The Making of a Black Leader, 1865–1901 (1972), and Booker T. Washington: The Wizard of Tuskegee, 1901–1915 (1983). A liberal thinker, Harlan was more critical of Washington than earlier biographers. His work also reflected the broader impact of the Civil Rights Movement and Black Power era in America since the 1950s. The rapid pace of change in these years made Washington's more patient conservatism appear unat tractive.The danger of this perspective was that it encouraged ahistorical thinking, judging Washington by the values of the 1960s and 1970s rather than those of his own day. An accomplished historian, Harlan took care to avoid this error and always strived to present the Tuskegeean's point of view even if he personally disagreed with it. His detailed knowledge of his subject, the result of more than 25 years of work on the collection of Washington's papers in the Library of Congress, gave him a depth of insight unequalled by previous and subsequent researchers. These factors combined meant that Harlan's two books remained unchallenged as the most authoritative biographical study of Washington at the end of the twentieth century. - eBook - PDF

Pauline E. Hopkins

A Literary Biography

- Hanna Wallinger(Author)

- 0(Publication Date)

- University of Georgia Press(Publisher)

From his humble southern origin he achieved a place of prominence in part through clever maneuvers, which were not always publicly known, that won him support at Tuskegee and gave him considerable political influence. 2 Washington published his autobiography, Up from Slavery, in 1901; it included a lengthy description of his “Atlanta Exposition Address,” given only six years earlier. In this speech Washington called upon African Americans to work for their salvation through industrial Portrait of Booker T. Washington in the New Era Magazine, February 1916. Courtesy of Black Print Culture Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Robert W. Woodruff Library, Emory University. Washington and Famous Men 73 progress and, to repeat his well-worn metaphor, to cast down their buckets where they were, in the American South. Agriculture, mechanics, commerce, domestic service, and the professions were the fields they should work in. Southern white people were asked to help this “most patient, faithful, law- abiding, and unresentful people” (Up from Slavery 148). In an attempt to assure the support of his white audience, he spoke against civil equality: “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” His politics of racial accommodation through segregation alienated many contemporary African Americans who thought that voting rights, higher education, and equal opportunities were essential to the progress of the race. His disdain of political activism and his conciliatory attitude about voting rights guaranteed him, however, the prominent position and political influence that helped him maintain the Tuskegee Institute and pursue a number of other political aims. The fact that he had many followers is also reflected in the political climate that preceded the passing of Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, the Supreme Court decision that legalized segregation on a large scale. - eBook - PDF

I Will Wear No Chain!

A Social History of African American Males

- Christopher B. Booker(Author)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

The structural and institutional racism, coupled with the range of racially prejudiced individuals functioning within the logic of these overarching systems, served to reinforce black self-doubt. With the fiinneling of money and influence through Booker T. Washington coupled with the disfranchisement of the masses ofblack males, a new leader was created. With his talent for sensing the desires of both southern and northern white political, cultural, and economic leaders, it is not surprising that his stated views dovetailed with theirs. As Washington's policy took concrete form, and he grew more powerful, an increasingly insistent criticism of his strategy and example began to be heard. William Monroe Trotter's example of an assertive masculinity continued a traditional ofblack middle-class behavior aided, in a new era, by a more powerful black community. While Booker T. Washington's visit to the White House caused a furor at the turn of the century, the Sage of Tuskegee was on his very best manners and merely elated to be there. Fifteen years later Trotter went toe-to-toe with President Woodrow Wilson, not waiting passively for respect, but rather demanding it. The overwhelmingly male character ofblack politics was reflected in the formation of the all-male American Negro Academy in 1897 and the Niagara Movement in 1905. Patriarchalism reigned in politics and ideology among African American males, reflected in the presumption of male leadership and dominance by leaders such as Alexander Crummell, WEB. Du Bois, and William Monroe Trotter. Yet, as the next chapter discusses, it was a woman who led the battle against the scourge of lynching. NOTES 1. A. J. Lane, The Brownsville Affair: National Crisis and Black Reaction (Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1971), 21. Washington, Accommodationism, and Masculinity 135 2. Ibid, 241. 3. Louis R. Harlan, Booker T. Washington: The Wizard of Tuskegee, 1901-1915 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 380. - eBook - PDF

African American Jeremiad Rev

Appeals For Justice In America

- David Howard-Pitney(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Temple University Press(Publisher)

3 The Jeremiad in the Age of Booker T. Washington Washington Versus Ida B. Wells, 1895–1915 THE SHARP REVERSALS of the late nineteenth century led to the rise of a new type of national African American leader and spokesman. The social and political contexts in which Booker T. Washington and Frederick Douglass operated were starkly different. At the height of Douglass’s influence during and shortly after the war, rapid strides toward black progress were made with significant white support; but from 1895 through 1915, when Washington was the leader with most national standing, blacks were struggling to save as many recent gains as possible against rising white opposition. Washington’s strategy accepted the apparent failure of Douglass’s comprehensive campaign against Anglo-American racism. Racism as a major white cultural convention and political force had not been extinguished nor lastingly diminished, as Douglass had hoped, but rather was increasing at the century’s end. Washington, therefore, did not overtly challenge white racism but worked to direct black efforts into educational and economic endeavors that did not openly threaten white social and political supremacy and that had a chance of gaining some white support. He considered it crucial for blacks to work to advance themselves in what he saw as the finally determinative field of social endeavor, and only one unaffected by racism, the American mar-ketplace. Whereas Douglass loudly publicly denounced white racism, Washington addressed soothing words to whites and turned away from their racist shortcomings. Washington advised blacks to accommodate 54 Chapter Three themselves to the presently unalterable prejudices of the white public while striving for achievement in the private sector. Booker T. Washington sometimes used variations of the American jeremiad in his rhetorical strategies, although his approach was quite different from most of the other jeremiahs examined in this study. - eBook - ePub

Book Matters

The Changing Nature of Literacy

- Alan Sica(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Booker T. Washington, Robert E. Park, and W. E. B. Du BoisOne of the lingering pleasures of the scholar’s existence resides, for a while yet, in gliding among the shelves of a large library, and finding by the grace of Mertonian serendipity a volume that should by virtue of its quality and utility be remembered and consulted, but is not— the bookish equivalent to shopping in Filene’s Basement or the local Goodwill store, uncovering a genuine preciosity amidst clutter, awaiting its rightful attention. The rediscovered book’s glory lies in its ability to shed light on matters of continuing concern, to contextualize debates that have not subsided, and perhaps most importantly, to illustrate yet again that social analysis has been carried out with great skill and subtlety long before anyone still alive was involved.So it was that The Man Farthest Down: A Record of Observation and Study in Europe (“The Struggle of European Toilers”) authored “by Booker T. Washington with the collaboration of Robert E. Park” recently came to hand by happy coincidence in its centenary year. It was copyrighted in 1911 by The Outlook Company, then issued in 1912 by Doubleday, Page and Co. in Garden City, New Jersey, and reprinted once, in 1984. Booker Taliaferro Washington remains famous through his autobiographies for being born into slavery in 1856, then miraculously achieving international celebrity as a champion of the oppressed. He vigorously disagreed with W.E.B. Du Bois concerning the most effective political and economic means for liberating the American “Negro,” a debate Du Bois recalled vividly in 1963 shortly before dying (McGill, 1965). By 1910, Washington was enduring morbid hypertension (at twice the normal rate), was “forced” by his nervous Tuskegee Institute staff to vacation in Europe, turned fifty-six when the The Man Farthest Down - E. Nathaniel Gates(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Dube had to overcome the suspicions of white South Africans who considered American Negro missionaries subversive. He earned the title of “the Booker T. Washington of South Africa” by sponsoring a type of education calculated to mollify the local whites and by his example of middle-class conservatism and dignity. He succeeded in gaining the support not only of white leaders but the militant African nationalists as well. After his election as president of the South African National Congress by the more militant Africans, Dube wrote to his American sponsors: “I believe in being moderate as you will see in my letter of acceptance, and I regard it as a duty to my people to keep in check, the red-hot republicanism that characterize[s] some of our leaders, and is calculated to injure rather than help our cause.” 74 A number of Dube’s graduates later attended Tuskegee. Another South African political moderate and educational leader, Davidson D. T. Jabavu, was more directly influenced by the Tuskegee educator. This graduate of the University of London spent three months at Tuskegee in 1913 under instructions from the South African Minister of Native Affairs to report on the adaptability of Tuskegee methods to South Africa. Jabavu and his father led in setting up the South African Native College at Fort Hare three years later. 75 A curious anomaly of the Washington Papers is his friendly correspondence with most of the leaders of African nationalism- eBook - ePub

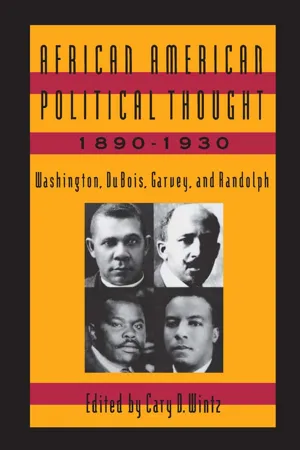

African American Political Thought, 1890-1930

Washington, Du Bois, Garvey and Randolph

- Cary D. Wintz(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

In the discussion of these questions it seems that we should bear in mind that agitation, as one gentleman said a minute ago, should have a very large and important part. That is proper. The condemnation of wrong should always have a very large and important place; the demands for rights withheld should have a large and important place; but a very large place in all of our discussion and in all of our efforts should be given to something that is constructive. Now, some of us live in the section of the country where we hear of these wrongs. We eat them for our breakfast, for our dinner, for our supper. We live on them day in and day out. Some of them we know pretty well. Along with the condemnation I hope that such a thoughtful body as this will turn its attention more and more in the constructive direction. What we can construct, what we can project, is what will bring us relief. I have great hope when I see such an intelligent and conscientious body doing something in this high-reaching and constructive period.Question—By REV . HARVEY JOHNSON : I believe what you say, that we must construct; we must do, if we can convince the people who are opposed to us that we can do. Have we not constructed something? Something that is operative. Has that construction effected or accomplished the end in view? Do you note any tendency on the part of the Southern white people to accord you justice on the score of the great, great work that you have accomplished in Alabama, or to accept you and yours and me and mine in this section more than before, because of that construction?PROFESSOR WASHINGTON : We have got to do our duty. In a great many cases you have got to wait patiently for results. If we keep on doing our duty, whether we see immediate results or not, the results will take care of themselves.13 Speech to the National Afro-American CouncilBooker T. Washington presented this address at the meeting of the National Afro-American Council in Louisville, Kentucky, on July 2, 1903. At this meeting Washington confronted growing criticism of his leadership, spearheaded by William Monroe Trotter, but Washington and his allies maintained control of the meeting. In his address, he urged blacks to remain patient and not give in to the urgings of extremists even in the face of increasing racial violence. This speech was printed in Ernest Davidson Washington, Selected Speeches of Booker T. Washington (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran and Co., 1932), 92–100, and reprinted in BTW Papers 7: 187–92 .Rights and Duties of the Negro

In the midst of the present deep interest growing out of matters connected with our race, it can be stated that recent events, as regretable as they are, have tended to simplify the problem in one direction at least. The events to which I refer show that the questions pertaining to our race are each day more and more becoming national ones, rather than local and sectional ones. When we carry the question up into the atmosphere where men of all races, North and South, will discuss it with calmness, with absence of passion and sectional feelings, I believe we shall have made a distinct advance.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.