History

Détente

Détente refers to a period of improved relations between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War. It was characterized by a reduction in tensions, increased diplomatic dialogue, and efforts to negotiate arms control agreements. Détente aimed to ease the threat of nuclear war and promote peaceful coexistence between the two superpowers.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Détente"

- Brian White(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

From this perspective, Détente was the product of a temporary balance of forces, was built upon a nuclear stalemate and was buttressed by a series of tangible and intangible agreements across the East-West divide. Thus, the period of Détente—broadly identified as the 1970s—can be characterized either by a specific set of agreements or less tangibly by a willingness to foster cooperative as well as conflictual relations. It can be defined as ‘a stabilised interstate system whose balanced configuration is the reference datum for the rest of international behaviour’ (Finley, 1975, p. 71). Coral Bell’s analysis of Détente as the product of a triangular relationship between Washington, Moscow and Peking fits neatly into this ‘power’ conception. She also stressed the ephemeral nature of Détente as a historical phenomenon with a reminder that ‘all Détentes in history have proved perishable in due course’ (see Bell, 1977, p. 71). These assumptions enable the prevailing balance of power to be used to explain a period of Détente and a changing structure of power to account for its passing.A second use identifies Détente as a prelude to entente. Though related to the first to the extent that Détente is seen as a function of certain structural factors, this conception identifies trends that push relationships beyond the ‘stage’ of Détente to much closer ties, variously labelled entente, rapprochement or even convergence. From this perspective, Détente is conceived as a sort of ‘half-way house’ between cold war conflict and entente: or, as Walter Clemens put it:a point on a logical spectrum of relations along which conflict either increases or decreases. If tensions mount, the parties may move towards cold and then hot war. If tensions diminish the parties move towards Détente—from Détente, they could move further towards rapprochement or even entente (Clemens, 1974, pp. 134–5).What appears to distinguish this final stage from Détente is the stability of the system. Richard Rosecrance, for example, concluded that nothing short of ‘a partial Soviet-American entente will provide the necessary structure in which present destabilising currents can be contained’ (Rosecrance, 1975, p. 481). Marshall Shulman drew a distinction between an ‘atmosphere of Détente’ and a ‘rapprochement or real stabilization’ (Shulman, 1966, p. 58).- eBook - PDF

Power and Protest

Global Revolution and the Rise of Detente

- Jeremi Suri(Author)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

The balance of power, in this context, created a stable inter-national equilibrium. This is the traditional interpretation of the origins of detente. 5 Balance-of-power explanations focus too narrowly on nuclear weapons. Leaders in the late 1960s worried more about domestic unrest than about nuclear war. They formulated foreign policy as a barrier against escalating internal turmoil. Great-power cooperation reduced the public tensions fu-eled by ideological conflict. Cold War antagonists now criticized each other less often, reduced their support for subversives, and more readily ignored their adversaries’ acts of repression. Detente had a powerful domestic com-ponent that exceeded a mere agreement to avoid nuclear armageddon. Responding to both domestic and international pressures in the late 1960s, leaders pursued what I call a balance of order. This involved a desper-ate attempt to preserve authority under siege. It emphasized stability over change, repression over reform. It was less about accepting nuclear parity than about manipulating political institutions to isolate and contain a vari-ety of nontraditional challengers. Detente brought together an international array of threatened figures who coordinated their forces to counterbalance the sources of disorder within their societies. The “peace” created by detente entrenched the social and political status quo. Cooperation among the great powers became a substitute for both do-mestic and international reform. It served as a balance against what policy-makers saw as unreasonable public expectations. Diplomatic arrangements made war less likely, but they also froze most of the initial sources of antago-nism in place. These circumstances could never provide a foundation for long-term harmony among states and peoples. The profound shortcomings of detente were evident in its immediate origins. - eBook - PDF

The Long Détente

Changing Concepts of Security and Cooperation in Europe, 1950s–1980s

- Oliver Bange, Poul Villaume, Oliver Bange, Poul Villaume(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Central European University Press(Publisher)

The Long Détente and the Soviet Bloc, 1953–1983 Csaba Békés There are several interpretations of Détente, but the prevailing idea in mainstream scholarship is that it was the period between 1969 and 1975 when the relaxation of tension in East-West relations produced spectacu-lar results. This included the settlement of relations between the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) and the Soviet Bloc states; U.S.-Soviet agreements on arms limitation and bilateral cooperation; and the conven-ing of a pan-European conference on security and cooperation, eventually culminating in the signing of the Helsinki Final Act. Détente Revisited There is formidable evidence to argue that Détente started in 1953 and ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 . The short period between 1953 and 1956 was a major landmark, after which the Cold War meant something else than before. During these formative years the most important trend in East-West relations was the mutual and gradual realiza-tion and understanding of the fact that the two opposing political-military blocs and ideologies had to live side by side and tolerate one another in order to avoid a Third World War, one waged by thermonuclear weapons, which would certainly lead to total destruction. Therefore the main char-acteristic in the relationship of the conflicting superpowers and their political-military blocs after 1953 was—despite the ever increasing com-petition in the arms race—the continual interdependence and compelled cooperation of the United States and the Soviet Union while imminent antagonism obviously remained. Ideological antagonism, competition, conflict, and confrontation remained constant elements of the Cold War structure but now they were controlled by the Détente elements: interde- 32 Csaba Békés pendence and compelled cooperation with the tacit aim of avoiding a di-rect military confrontation of the superpowers. - eBook - PDF

Honey and Vinegar

Incentives, Sanctions, and Foreign Policy

- Richard N. Haass, Meghan L. O'Sullivan, Richard N. Haass, Meghan L. O'Sullivan(Authors)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- Brookings Institution Press(Publisher)

At a time when the Soviet regime was paying greater costs to preserve the empire (having invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968 to subdue the Prague regime and its population) and was facing the rise of a dissident movement internally, detente could provide Moscow with economic, politi-cal, and military benefits that could strengthen Brezhnev's hold on power even further. The Elements of Detente The most public features of detente were the presidential summits and the arms control agreements, but the policy was much more, including agree- 124 JAMES M. GOLDGEIER ments dealing with postwar European borders, trade, cultural exchanges, and rhetorical promises regarding codes of conduct. In 1971, the United States, Britain, France, and the USSR signed the Quadripartite Agreement on Berlin, which resolved issues of Western access and removed this long-standing problem as a potential flash point. In May 1972, the superpowers signed the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, limiting development and deployment of defensive systems, and agreed on an interim accord (which became known as SALT I) to limit the number of offensive nuclear launch-ers. They also signed a document known as the Basic Principles Agreement, which stated that the two countries would proceed from the common de-termination that in the nuclear age there is no alternative to conducting their mutual relations on the basis of peaceful coexistence; they would de-velop normal relations based on the principles of sovereignty, equality, non-interference in internal affairs and mutual advantage; they pledged to avoid confrontations that might lead to nuclear war; and they stated their recog-nition that efforts to obtain unilateral advantage at the expense of the other, directly or indirectly, are inconsistent with these objectives. - eBook - PDF

Winning the World

Lessons for America's Future from the Cold War

- Thomas Nichols(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

THE LESSONS OF DETENTE As with "engagement" in the late twentieth century, detente was a policy that drifted in conflicting directions because it had no clear goals other than a general desire to avoid war. On the one hand, it seemed to accept the immutability of the USSR and strove only to manage the inevitable tensions that would arise between the United States and the Soviet Union as, respectively, the dominant power and the challenger. On the other hand, it carried a pedantic undertone, a belief that the The Limits of Detente 133 Soviets would internalize the norms of the international system by participating in it, especially if their aspirations to legitimacy were taken seriously. This, as John Gaddis has pointed out, was the "patron- izing" side of detente, a belief that the Soviet Union could be trained "like some laboratory animal." 62 Kissinger would no doubt argue that this attempt to constrain the Soviets by involving them as a partner in the international status quo only reflected the Nixon team's confidence that detente should have been allowed to stand the "test of time" rather than being subverted by Jackson and other hard-line anticommunists. 63 This is essentially the same confusion in American policy with regard to China and other challengers in the twenty-first century: realists press for engagement as a means of averting misunderstanding and manag- ing tensions, with the most optimistic Westerners certain that there is little wrong with China that a decade of American fast food and Internet access cannot cure. Based on an obstinate realism that refused to come to terms with the unyielding ideological agenda of the opponent, detente did little to slow Soviet advances in strategic arms (although it restrained American research), lessen the worrisome imbalance in Europe (although Soviet propaganda managed to strain relations between NATO and the United States), or halt Soviet forays into the Third World (even as the Ameri- cans retreated from it). - eBook - ePub

Constructive Illusions

Misperceiving the Origins of International Cooperation

- Eric Grynaviski(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Cornell University Press(Publisher)

2

DÉTENTE

There will be much talk about the necessity for “understanding Russia”; but there will be no place for the American who is really willing to undertake this disturbing task. The apprehension of what is valid in the Russian world is unsettling and displeasing to the American mind. He who would undertake this…the best he can look forward to is the lonely pleasure of one who stands at long last on a chilly and inhospitable mountaintop where few have been before, where few can follow, and where few will consent to believe he has been.GEORGE KENNAN , SEPTEMBER 1944During the early 1970s, the United States and the Soviet Union began a remarkable process of cooperation intended to develop an enduring relationship that would end the excesses of superpower competition. Superpower cooperation was so successful that many prognosticators predicted the end of the Cold War. Perhaps most impressive was the timing. Détente occurred less than ten years after the Cuban Missile Crisis, at the height of the Vietnam War, and nine years before the Soviet incursion in Afghanistan. What enabled the United States and the Soviet Union to improve relations? Was the change from what Richard Nixon called an “era of confrontation” to an “era of negotiation” premised on mutual understanding?Kennan’s statement in the epigraph to this chapter—that one who understands Russia is of no use in American foreign policy and the effort to do so will leave such a person alone “on a chilly and inhospitable mountaintop”—may seem strange to students of diplomacy and international politics. In the previous chapter, I showed that IR theorists often explain peace and cooperation as a product of mutual understanding. In particular, constructivists might argue that the shift in this case from mortal enemies to cooperative rivals was the result of a change in the superpowers’ social relationship.1 The early years of the Cold War, rooted in enmity and ideological warfare, gave way to rivalry and coexistence. These scholars highlight the importance of shared ideas—intersubjectivity—in managing the superpower rivalry.2 - eBook - PDF

A Journey through the Cold War

A Memoir of Containment and Coexistence

- Raymond L. Garthoff(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Brookings Institution Press(Publisher)

14 Developing Détente in U.S.-Soviet Relations A s we have seen, the course of the Cold War oscillated between periods of greater and lesser tension, between confrontation and Détente. The first significant lessening of tension had come after the death of Stalin, in the period from 1953 to 1956. The Soviet suppression of the Hungarian uprising and renewed pressures on Berlin worsened relations, and the Berlin crisis of 1961 and the Cuban missile crisis of 1962 ensued. A new Détente had emerged in 1963–64, but the war in Vietnam and Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968 again brought tension. President Richard Nixon, with a reputation as a hard-line anticommunist ever since he entered politics in the late 1940s, nonetheless came into office in 1969 calling in his inaugural address for an “era of negotiation” to replace an era of confrontation, and with the avowed goal of building “a structure of peace.” 1 Later, Nixon championed “a new strategy of peace,” knowingly or not echoing President Kennedy’s American University speech of June 1963. Nixon did not use the word “Détente” in his inaugural address, or indeed for more than a year, but the concept was clearly there. There was an interest-ing insider feature of that first presidential public statement. Included in Nixon’s address was a seemingly routine reference that “all nations” should 1. “Inaugural Address of President Richard Milhouse Nixon,” January 20, 1969, Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents, vol. 5, January 27, 1969, pp. 152–53. I have exam-ined the American—and Soviet—conceptions of Détente, and the entire course of U.S.-Soviet relations in the period from 1969 through 1980, in some detail in Raymond L. Garthoff, Détente and Confrontation: American-Soviet Relations from Nixon to Reagan, rev. ed. (Brookings, 1994). - eBook - PDF

America's Strategic Blunders

Intelligence Analysis and National Security Policy, 1936–1991

- Willard C. Matthias(Author)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- Penn State University Press(Publisher)

The summit itself was primarily concerned with the Anti-Ballistic Missile The Nixon Era and the Beginning of Détente 247 Treaty. But there were two associated seminal documents, both more politi- cal and atmospheric in tone than the hard legal language which dealt with military weaponry. One was “Basic Principles of Relations” between the United States and the USSR. The signatories agreed to “do their utmost to avoid military confrontations and to avoid the outbreak of nuclear war.” They were “prepared to negotiate and settle differences by peaceful means.” They would continue the practice of “exchanging views on problems of mutual interest” and would try to do this at the highest level. They would “continue their efforts to limit armaments—with the objective of general and complete disarmament.” They would strengthen their commercial and economic rela- tions and develop cooperation in science and technology. The other declaration in the communiqué was a reference to a “European Security Conference” similar to declarations contained in Soviet treaties with America’s European allies. This declaration led to the Helsinki Accords signed in 1975, which have proved more important than was believed at the time. They recognized the national independence and the existing borders of the countries of Europe. They were honored by the Soviets fifteen years later when popular revolts unseated pro-Soviet regimes in Eastern Europe and resulted in the withdrawal of Soviet military forces. Soviet Military Policy in Transition U.S. and Soviet military doctrines and capabilities were the principal rea- sons for the Détente movement. Each side was hiding under its nuclear umbrella to improve its geopolitical position, and each in turn feared trig- gering the other’s nuclear attack capability during a critical confrontation. That is why it became incumbent upon both parties to promise to negotiate differences and to exchange views on matters of mutual interest. - eBook - PDF

Re-Viewing the Cold War

Domestic Factors and Foreign Policy in the East-West Confrontation

- Patrick M. Morgan, Keith Nelson(Authors)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

"It be- came increasingly evident," he says, "beginning even in the early 1970s when de- tente was at a high point, that Washington and Moscow had very different conceptions of what a detente policy entailed, and had had from the outset." 5 These authors suggest either that Nixon's goals were too limited or that the rela- tionships he built were simply not well constructed. Whichever historian one prefers, the question inevitably remains: Why was the detente that Nixon espoused and created not a more thorough-going reform and/or a more stable condition? Could it be that his endeavors were subtly transformed or undermined by America's allies abroad? Or was he blocked from achieving his real objectives by the situation at home? by the governmental bureaucracy? by the Congress? by the public? Or did Nixon's own beliefs and/or techniques put limits on what he strove for and accomplished? Or did he simply find himself constrained by what he could persuade his various Communist opponents to accept? Such que- ries cry out for a careful multilevel analysis. 6 It is the intention of this chapter, then, to scrutinize Nixon's foreign policy to- ward the Communist world, especially during his first term, to see how domestic and foreign games interacted so as to determine its shape and to establish its re- sults. Such an examination will serve to demonstrate that domestic and per- sonal factors have been undervalued in most explanations of detente and that they played a crucially important role both in driving Nixon to action and, ulti- mately, in limiting the nature of his initiatives. This was the moment of the Cold War when there was perhaps the greatest chance for breaking through to real peace, when the public (at home and abroad) was probably more receptive to radical change than ever before, but Nixon, sadly, was unable fully to seize the opportunity. - eBook - PDF

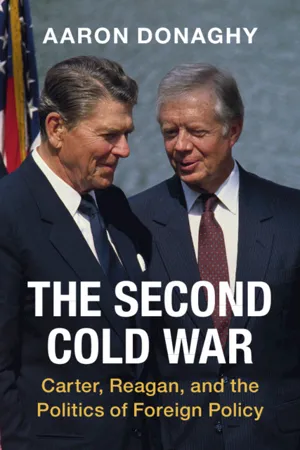

The Second Cold War

Carter, Reagan, and the Politics of Foreign Policy

- Aaron Donaghy(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

In May 1976, the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group was formed to monitor human rights violations and report their findings to the foreign media. Similar watch groups were founded in Soviet republics 28 The Second Cold War such as Ukraine, Georgia, Lithuania, and Armenia. Human rights move- ments also gathered pace outside of the USSR. In January 1977, a group of dissident Czechoslovak intellectuals published a manifesto titled “Charter 77,” which demanded that the Helsinki Accords be put into practice. As Carter took office, Soviet dissidents (relatively few in number) were calling for similar action. 44 For Brezhnev, bilateral relations (e.g., trade, arms control) were more important than squabbles over human rights. The Soviet leader delivered a goodwill speech in Tula two days before Carter’s inauguration. Its purpose was to publicly convey the Soviet foreign policy approach. He renounced the pursuit of military superiority, endorsed efforts to achieve a new SALT Treaty, and explained his views on Détente. “Détente is above all an overcoming of the ‘cold war,’ a transition to normal, equal relations between states,” Brezhnev declared. “Détente is a readiness to resolve differences and conflicts not by force, not by threats and saber-rattling, but by peaceful means, at the negotiating table. Détente is a certain trust and ability to take into account the legitimate interests of one another.” 45 But Détente had not dissuaded Moscow from amassing larger stock- piles of nuclear weapons. Soviet leaders were pursuing two diverging policies at once: Détente on the one hand; and a military buildup on the other. “During those years we were arming ourselves like addicts, without any apparent political need,” recalled Georgy Arbatov, the Kremlin’s chief adviser on American affairs. 46 In 1976 the Soviet Union began deploying a new intermediate-range missile system, known as the SS-20.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.