History

Embargo of 1807

The Embargo of 1807 was a law passed by the United States Congress that prohibited American ships from trading with foreign nations. It was enacted in response to British and French interference with American shipping during the Napoleonic Wars. The embargo had a significant impact on the U.S. economy, leading to widespread smuggling and economic hardship, and was eventually repealed in 1809.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

9 Key excerpts on "Embargo of 1807"

- eBook - ePub

Economics

The Definitive Encyclopedia from Theory to Practice [4 volumes]

- David A. Dieterle(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

Beyond Reaganomics: A further enquiry into the poverty of economics. Notre Dame, IN: Univ. of Notre Dame Press.EMBARGO ACT OF 1807The Embargo Act of 1807, signed into law by President Thomas Jefferson on December 22, 1807, was created as an attempt to stop France and Britain, which were at war with each other, from restricting American trade. The purpose of the Embargo Act of 1807 was to introduce a form of nonviolent resistance to British and French interference with U.S. merchant ships. It effectively restrained American trading overseas until March 1809.The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) can be viewed as the origin of the Embargo Act. Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte of France was determined to build a great empire. Beginning in 1803, a series of wars erupted between the French under Napoleon and the British. Each side possessed very different military strengths: With Napoleon’s power based on the strength of his land armies, and British strength displayed in its naval fleet, it was difficult for the parties to engage each other in battle. Therefore, the French and the British ventured to inflict damage in another way: by attacking each other’s trade and commerce. To illustrate, the British attacked the French by declaring Continental ports closed to commerce. As retaliation against the British, the French declared all British commerce to be unlawful. These circumstances meant that neither British nor European ships could carry on trade.However, the two enemies’ attacks on one another created a rather lucrative situation for American ships. As a result of the French and British policies, the United States could make profits by trading without any competition. Unfortunately, British shipowners were enraged and demanded that the British government put an end to trading with America. Old British laws were resurrected and enforced, and any American ships that violated these laws were to be seized by the British. Both the French and the British would seize any U.S. ship that was caught entering harbor. - eBook - PDF

Creating the Administrative Constitution

The Lost One Hundred Years of American Administrative Law

- Jerry L. Mashaw(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Yale University Press(Publisher)

92 reluctant nationalists infeasible. 5 Yet to accept British and French depredations on American commerce was as insufferable as war seemed disastrous. The alternative, promoted jointly by Jefferson and by Madison, his Secretary of State, was an embargo on all transport of goods from U.S. ports to foreign destinations. 6 The Embargo of 1807–1809 was novel in two separate senses. First, it was novel as a matter of foreign policy because the nation had never before ex-perimented with such an extensive form of peaceful coercion. 7 Nonimpor-tation statutes and temporary or limited embargoes respecting a particular country were relatively common, but Jefferson proposed a complete embargo with no fixed term on all foreign commerce. His purpose was “to keep our seamen and property from capture, and to starve the offending nations.” 8 The first purpose, if the embargo could be put into effect, would surely be successful: 9 American maritime assets could not be captured on the high seas if they were all in port. Starving the offending nations was surely more problematic, but not wholly implausible. British and French colonies in the Caribbean were highly de-pendent upon American trade for most of the necessities of life, 10 and the dependence of British manufacturers on American cotton and other com-modities was significant. 11 There is substantial evidence both that the em-bargo dramatically curtailed foreign trade and that the negative economic impact on Great Britain was greater than the admittedly harsh effects on American commerce, agriculture, and manufacturing. 12 The embargo was ultimately a political, not an economic, failure. 13 Second, the embargo was a commercial regulatory experiment of equal or greater novelty. Mercantilist trade regulation by the great European pow-ers had long subjected their commerce to pervasive governmental control. And for a host of purposes states and localities in the United States heavily regulated internal commerce. - eBook - PDF

The Life of Daniel Waldo Lincoln, 1784-1815

Letters from a Wayward Son

- Rebecca M. Dresser(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

He would put an end to all foreign trade. The idea was that without American goods, without ships on the ocean that could be assaulted, without American sailors to be impressed, both France and Britain would be forced to quickly capitulate and stop the harassment. He knew that such a step would be painful, but he also knew that his puny navy was massively outmanned and outgunned by the British. An embargo would give him time to reassess and rebuild his military with the hope that the two European nations would come to terms in the meantime. Accordingly, on December 22, 1807, Congress passed the first of Jefferson’s Embargo Acts. American vessels were prohibited from all foreign trade, forcing them to rely on do- mestic trade exclusively. When small craft and fishing vessels continued to sail anyway, thinking that they were exempt from the trade restrictions, they quickly learned otherwise when two even harsher laws followed. Those who attempted to evade the law by either smuggling goods into Canada or loading their goods on foreign vessels faced severe reprisals. 3 The effects of the embargo came down hard and fast on Portland, whose shipping commerce had been the bedrock of the town’s prosperity. Within weeks Portland’s economy began to crumble. Eleven commercial houses went bankrupt. By the end of 1808, thirty mercantile firms had failed. Customs receipts plummeted from $340,000 in 1806 to $41,000 in 1808. Unemployment rose to sixty percent. Poor houses filled up, soup kitchens opened, ships sat idle and rotting in the harbor while grass grew on the neglected wharves. Portland’s hey-day of prosperity made the once lovely town a wilted rose in the desert, still beautiful but withered and fragile. Merchants and seamen in the town grew desperate and angry. Among the failed businessmen was John Taber, a tanner by trade who like many others, had built his business during Portland’s heyday. A Quaker, Taber enjoyed a reputation for uncontestable honesty and integrity. - eBook - ePub

- Edward Sylvester Ellis(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

The purchase of Louisiana, which at one stroke more than doubled the existing area of the nation, was at first hotly opposed, especially by the Federalists. It was deemed by them an unwarrantable stretch of the Constitution on Jefferson's part, both in negotiating for it as a then foreign possession without authority from Congress, and in pledging the country's resources in its acquisition. The President was, however, sustained in his act, not only by the Senate, which ratified the purchase, but by the hearty approval and acclaim of the people. Happily at this time the nation was ready for the acquisition and in good shape financially to pay for it, since the country was prospering, and its finances, thanks to the President's policy of economy and retrenchment, were adequate to assume the burden involved in the purchase. The national debt at this period was being materially reduced, and with its reduction came, of course, the saving on the interest charge; while the national income and credit were encouragingly rising. Though the economical condition of the United States was thus favorable at this era, the state of trade, hampered by the policy of commercial restriction against foreign commerce, then prevailing, was not as satisfactory as the shippers of the East and the commercial classes desired. The reason of this was the unsettled relations of the United States with foreign countries, and especially with England, whose policy had been and still was to thwart the New World republic and harass its commerce and trade. To this England was incited by the bitter memories of the Revolutionary war and her opposition to rivalry as mistress of the seas. Hence followed, on the part of the United States, the non-Importation Act, the Embargo Act of 1807-08, and other retaliatory measures of Jefferson's administration, coupled with reprisals at sea and other expedients to offset British empressment of American sailors and the right of search, so ruthlessly and annoyingly put in force against the newborn nation and her maritime people. The English people themselves, or a large proportion of them at least, were as strongly opposed to these aggressions of their government as were Americans, and while their voice effected little in the way of amelioration, it brought the two peoples once more distinctly nearer to the resort to war. Meanwhile, the Embargo Act had become so irritating to our own people that the Jefferson administration was compelled to repeal it, though saving its face, for the time being, by the enforcement of the non-intercourse law, which imposed stringent restrictions upon British and French ships entering American harbors.Such are the principal features of the Jefferson administration and the more important questions with which it had to deal. Among other matters which we have not noted were the organization of the United States Courts; the removal of the seat of government from Philadelphia to Washington; the party complexion of Jefferson's appointments to the civil service, in spite of his expressed design to be non-partisan in the selection to office; and the naming of men for the foreign embassies, such as James Monroe as plenipotentiary to France, assisted at the French Court by Robert R. Livingstone, and at the Spanish Court by Charles C. Pinckney. Other matters to which Jefferson gave interested attention include the dispatch of the explorers, Lewis and Clarke, to report on the features of the Far Western country, then in reality a wilderness, and to reclaim the vast unknown region for civilization. The details of this notable expedition up the Missouri to its source, then on through the Indian country across the Rockies to the Pacific, need not detain us, since the story is familiar to all. With the Louisiana purchase, it opened up great tracts of the continent, later on to become habitable and settled areas, and make a great and important addition to the public domain. In the appointment of the expedition and the interest taken in it, Jefferson showed his intelligent appreciation of what was to become of high value to the country, and ere long result in a land of beautiful homes to future generations of its hardy people. - eBook - ePub

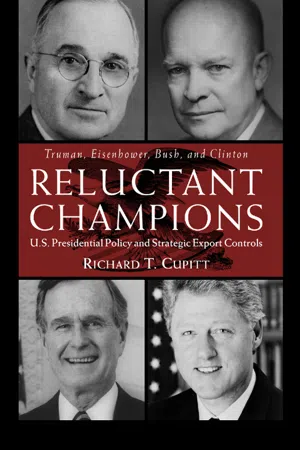

Reluctant Champions

U.S. Presidential Policy and Strategic Export Controls, Truman, Eisenhower, Bush and Clinton

- Richard T. Cupitt(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Instead of calling Congress into a special session to declare war, President Jefferson tried to defuse the conflict through diplomacy, and sent an emissary to Britain. The British removed the officers responsible for the attack, returned three of the sailors (the British Navy had hung the fourth), and offered to pay an indemnity to the victims or their relatives. The British government did not, however, agree to stop the practice of searching for deserters on U.S. ships.When diplomatic efforts failed to resolve the issue, President Jefferson sought another means of influencing the British. The American colonies had boycotted English goods in 1765 and again in 1767–1770, eventually forcing Britain to repeal the Stamp Act and the Townshend Acts (except for the measures on tea). President Jefferson turned to a similar economic sanction by proposing a policy of “peaceable coercion” embodied in the Embargo Act of December 22, 1807.3With the Embargo Act, the U.S. government forbade any ships to leave U.S. ports for foreign shores freely. Regarding the expected impact, Secretary of State James Madison declared, “We send necessities to her [England]. She sends superfluities to us. Our products they must have. Theirs, however promotive of our comfort, we can to a considerable degree do without.” 4 Under the act, traders had to obtain government approval before loading goods on ships, coastal shippers had to post a bond of double the value of the goods, and the government could confiscate cargo or ships involved in illicit trade.5In the next year, U.S. exports declined precipitously, from $108 million to $22 million.6 Imports from England fell by one half, and U.S. inflation soared. An estimated 100,000 sailors, shipbuilders, and others lost their jobs.7 Though New England and New York felt the brunt of the policy (partially mitigated by the increase in overland exports into Canada), the embargo also hurt exporters of Western and Southern forest or agricultural products badly. While the fall in trade did raise prices in England and elsewhere, the British did not change their policy.The Embargo Act revived the Federalist party in the election of 1808. Though the Federalists did not regain control of the government, their success helped push President Jefferson to moderate the export restrictions. In March 1809, President Jefferson replaced the Emargo Act with the Non-Intercourse Act of 1809, three days before James Madison became president. Subsequently, the Madison administration negotiated a diplomatic solution to the problem. In April of 1809, U.S. Secretary of State Robert Smith exchanged diplomatic notes with the British Minister in Washington, David Erskine, which temporarily resolved some of the more egregious issues. Nonetheless, the British repudiated the Erskine Agreement (the first important executive agreement made by the United States) only a few months later, when a more hostile representative of the Crown replaced Minister Erskine. After a series of progressively milder measures, Congress passed Macon’s Bill No. 2 (May 1, 1810), which reopened U.S. ports.8 The policies of the belligerents continued to harm U.S. shipping, however, so the bill contained a discriminatory provision. If either Britain or France revoked their orders-in-council or decrees, and the other government did not do the same within three months, then the United States would reimpose its embargo on that state. The French said their Berlin and Milan decrees would no longer affect U.S. shipping after November 1, 1810, although this did not mark any real change in French policy.9 Consequently, President Madison reconstituted the nonimportation provisions against England on February 2, 1811.10 - eBook - PDF

Prologue to War

England and the United States 1805-1812

- Bradford Perkins(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

Clements Library. See also Herbert Heaton, "Non-Importation, 1806-1812," Journal of Economic History, I (194.1), 187. 4 5 Jefferson to Cabell, March i j , 1808, Jefferson MSS. 162 E M B A R G O the law to mean that merchants might export American goods to exchange for foreign wares contracted for but not paid for prior to December, 1807. Jefferson and Gallatin did confine most of the operation of this clause to goods from the West Indies rather than from Europe. Nevertheless, it had serious results. In a report covering only the period to the end of September, the President acknowledged that 594 vessels totaling some 87,000 tons had re- ceived permission to sail} by December more than 400 of these ships had returned with cargoes which relieved the pressure upon British exporters. 46 Departures continued until January, 1809, just before the entire system collapsed in ruins. The legislative history of the Embargo, which clearly shows the problems the administration had to face, also demonstrates the gradual rise to predominance of the coercive motive. Within a month after the original act, its deficiencies made necessary a sup- plementary law extending controls to the coasting trade, fisheries, and whaling, and establishing a complex system of bonds and penalties to give teeth to enforcement. In March Congress passed a second supplement. Its chief purpose was to outlaw exportation to Canada. Thus Congress demonstrated that the protection of ships and seamen and their withdrawal as a possible prelude to war were not the only motives for the Embargo system. In a speech that nearly got him expelled from the House, Barent Gardenier charged that the original act had been "a sly, cunning measure," designed to appear as a precautionary measure but really intended as the first shot in a campaign of pressure on Britain. - eBook - ePub

- Lawrence Karson(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

32The first of a series of non-importation and embargo laws was passed in early 1806 in an attempt to influence the British by limiting the importation of various non-critical manufactured goods; with ongoing diplomatic trade discussions with Britain, the law was, but for one short period, not implemented until late in the following year.33 But by the end of the year, Jefferson and the Republican Congress passed the first embargo law, one of draconian wording for American commerce. The law prohibited all ships and vessels from clearing for a foreign port and demanded the payment of a bond equal to double the value of the vessel and cargo in order to guarantee that those vessels with cargoes claiming to be bound for another domestic harbor would, in fact, re-land the cargo in some port of the United States.34 Jefferson’s political agenda, originally enforced by this sequence of restrictive maritime laws (as the British had previously attempted), brought his administration into direct conflict with the business interests of the economic elite of the American Northeast.The embargo legislation was followed by two more laws, tightening the loopholes in the original statute. Licensed coastal traders, fishing, whaling, and other small vessels were incorporated into the embargo requirements with fishing and whaling vessels required to post a bond at four times the value of the vessel and cargo, and licensed vessels ‘confined to rivers, bays and sounds’ posting a bond of three hundred dollars per ton of vessel. The statute also designated penalties for violating the embargo, including forfeiture of vessel and cargo for departing without a permit or for being involved in any prohibited foreign voyage. The master or any other persons concerned with the trade were subject to a fine of one thousand to twenty thousand dollars, with the owner liable for twice the value of the ship or vessel and cargo if the vessel was not seized. Foreign vessels were also prohibited from shipping ‘specie or any goods, wares or other merchandise’, they also being subject to seizure and forfeiture. The next law limited the length of time a coastal trader was allowed to complete its journey to four months, and it addressed the smuggling traffic to and from Canada by authorizing the seizure of land conveyances of contraband goods and penalties of up to ten thousand dollars for those involved, setting bonds for foreign vessels domestically re-landing cargo to four times the value of the vessel and cargo, lowering to two hundred dollars per ton for vessels ‘confined to rivers bays, sounds and lakes’. It also eliminated bonds for vessels not masted or, if masted, not decked and confined to rivers, bays, and sounds in areas not adjacent to foreign territory. Finally, the president was authorized to grant permission to citizens of the United States to send vessels in ballast to recover and import property held outside the United States prior to December 22, 1807.35 - eBook - ePub

- William E. Dodd(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Braunfell Books(Publisher)

Our ships were to keep close in the harbors or high up the rivers, no foreign trader was to depart without special orders from the President on pain of confiscation; the coast traders were to dart in and out from harbor to harbor like spring chickens dodging a hawk. Ship-owners and traders were to be fined twice the value of each ship if found violating the provisions of the proposed law and all the forces of the army and navy were to be placed at the disposal of the Executive for its effective enforcement. {216} In a few days the embargo was before Congress and within four days it became a law with all the clauses necessary for the enforcement of the ideas pointed out above. Never did a President have his wishes more speedily complied with. The embargo was an experiment and a reasonable one; there was no ground for doubting that it would bring England to terms if it were enforced strictly everywhere for one or two years. Warring Europe was in need of supplies which America chiefly furnished. But, as already said, the enforcement was the question and many doubted the ability of the government to enforce a law which required large numbers of wealthy men to close up their business. {217} The law went into effect at once and complaints and petitions began to pour in upon the President and Congress. Macon approved of the embargo especially since it would render increase of the navy unnecessary; Randolph at first favored but finally opposed it. But the plan was in full accord with the political principles of both Randolph and Macon. {218} Evasion of the law became general at once in the maritime States and England lent her assistance. Canada was made a dumping ground for New England merchants. On Lake Champlain New England traders defied the officers of the United States and carried their goods in triumph past the custom houses - eBook - ePub

The Ninth State

New Hampshire's Formative Years

- Lynn Warren Turner(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- The University of North Carolina Press(Publisher)

10 Even the people sympathetic with Jefferson, however, regarded the embargo as at best only a temporary nuisance and a necessary evil. Writing to an old friend in the Senate, William Plumer declared thatI am an advocate for the freedom of commerce, but presume congress when they imposed the embargo, possessed information of danger to which our commerce was exposed, which it was then improper to disclose, but which if known, would have prevented prudent men from hazarding their ships on the ocean. When this danger shall, from any source whatever, be known to our merchants, will the embargo be continued, or is it designed to operate against other nations? If the latter is the object, I fear while we are chastising them with whips , we shall be scourging ourselves withscorpions.11It seems superfluous to say that New Hampshire suffered from the embargo. It was never supposed, even by the most sanguine Republican, that a sudden and violent enforcement of economic autarchy could be painless. New Hampshire’s Jeffersonians regarded the measure with wry distaste, but defended it loyally. As their recently established organ, The American Patriot of Concord, admitted:The embargo is a medicine prescribed by the government for the recovery of commerce, and although it is a little nauseous will produce eventual good…. There is one [other remedy]. It is war . But that… is a desperate medicine, and ought never to be used but in the last resort. A skilful physician never uses mercury when a milder preparation will suffice; And our administration have not thought it prudent to rack the republic with an agonizing specific whilst a more lenient application would answer.12For New Hampshire, this somewhat specious argument held more validity than for other New England states. The immediate weight of the embargo fell upon the shipowners and shipbuilders of the Piscataqua region, yet the registered tonnage of New Hampshire vessels engaged in foreign trade decreased but slightly between 1807 and 1808.13 The greatest sufferers were those whom many regarded as parasites anyway—the merchants engaged in the carrying trade. Reexports of foreign produce from Portsmouth plummeted from $ 314,072 to $ 2,765 during the embargo years.14

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.