History

Sedition Act of 1918

The Sedition Act of 1918 was a U.S. law that made it illegal to criticize the government, the Constitution, the military, or the flag during wartime. It was enacted during World War I and was aimed at suppressing dissent and opposition to the war effort. The act was controversial and led to numerous arrests and prosecutions of individuals expressing anti-war sentiments.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Sedition Act of 1918"

- eBook - ePub

Treasure State Justice

Judge George M. Bourquin, Defender of the Rule of Law

- Arnon Gutfeld(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Texas Tech University Press(Publisher)

54The Sedition Act was designed to stop dissent. On May 28, 1918, the Anaconda Standard correctly interpreted its significance: “There is no freedom of speech any longer for the disloyal or pro-German. A man can talk all he pleases if he talks right.” Thus, an alleged violation of a federal law in a small town in Montana, a courageous decision by a judge who could not be intimidated by a patriotic mob, and the extraordinary hysteria that engulfed a state and a nation contributed in large measure to the passage of one of the most stringent anti–free speech acts in American history.The events of 1917–18 left an indelible impression on many of the primary actors involved. Burton K. Wheeler, for example, wrote: “One reason why I was oppose [sic] to F.D.R. packing the Supreme Court in 1937 was because of my experience during that time [World War I]—the local courts were crazy; only…Judge Bourquin and a few other local Federal Courts stood up.”55 Wheeler was correct; very few in the legal profession opposed the national hysterical “patriotic” orgy.56Brutal stifling of the rights guaranteed by the Constitution followed the passage of the Sedition Act of 1918.57 The act stemmed from local and national fears of radicals compounded by astute manipulation of patriotic feelings by business interests within a nation at war. President Wilson's Mediation Commission concluded that the unrest in the mining and lumber industries had not been the result of treasonable plots by the IWW but rather was triggered primarily by employers dealing with “unremedied and remediable industrial disorders.”58 The Justice Department, recognizing the wide scope of the act and the danger to individual liberties inherent within it, urged district attorneys to enforce the act with discretion. The department did not want wholesale suppression of legitimate criticism of the government.59 - eBook - ePub

No Law

Intellectual Property in the Image of an Absolute First Amendment

- David L. Lange, H. Jefferson Powell(Authors)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Stanford Law Books(Publisher)

The Republican opposition of 1917 10 provided most of the criticism and most of the votes to defeat the press censorship provision, but most Republicans wished only to soften, not to defeat the proposed legislation, and President Wilson’s fellow Democrats in turn were not monolithic in support of the administration’s preferences. The 1917 Act did not play the polarizing role in political-party ways which the 1798 Act had done. Nevertheless, the Espionage Act—the first federal seditious libel legislation since 1798—clearly raised, for many people, issues akin to those presented by the Sedition Act. “Never in the history of our country, since the Alien and Sedition Laws of 1798, has the meaning of free speech been the subject of such sharp controversy as to-day,” civil libertarian Zechariah Chafee, Jr. wrote in the middle of the discussion. 11 As Chafee’s observation suggests, the Sedition Act and its impact on constitutional law were important to the discussion of the Espionage Act. But what, in fact, was that impact? The answer, it seems, was rather ironic. As a political matter, within a few years after the Sedition Act’s expiration in March 1801, many Americans looked back on the period between 1798 and 1801 as a temporary aberration - eBook - PDF

Kentucky and the Great War

World War I on the Home Front

- David J. Bettez(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- The University Press of Kentucky(Publisher)

4 Opposition to the War During World War I, freedom of speech in the United States was often cur- tailed in the name of loyalty and patriotism. With help from the states, the fed- eral government tried to suppress opposition to the war, which it interpreted as sedition. Government officials, however, struggled with the difference between freedom of speech and sedition. Moving quickly after the United States entered the war, Congress on June 15 passed the Espionage Act of 1917. Under the act’s terms, people were sub- ject to fines up to $10,000 or imprisonment up to twenty years, or both, if they made “false reports or false statements” that might interfere with the success of the US military or promote the success of its enemies; attempted to cause or caused “insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty” in the military; or willfully obstructed enlistment or recruiting efforts. 1 To bolster this law, which appeared ambiguous and weak to some people, the following May the federal government passed “an even more draconian amendment,” the Sedition Act of 1918, which forbade “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” about the US form of government, the Constitution, the military and naval forces, or the US flag. 2 The federal government’s efforts to enforce these acts involved major agen- cies: the Treasury Department’s Secret Service, the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation (BI), the US Army’s Military Intelligence Division, and the US Navy’s Office of Naval Intelligence. Eventually the Bureau of Investigation led the effort under its chief, Alexander Bruce Bielaski. He reported directly to US attorney general Thomas Watt Gregory, although the director of Gregory’s War Emergency Division, John Lord O’Brian, and O’Brian’s assistant, Alfred Bett- man, usually handled sedition matters. - eBook - ePub

The Safety of the Kingdom

Government Responses to Subversive Threats

- J. Michael Martinez(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Carrel Books(Publisher)

Chapter 3 THE ESPIONAGE ACT OF 1917 AND THE Sedition Act of 1918—SENATOR ROBERT M. FOLLETTE SR.,I think all men recognize that in time of war the citizen must surrender some rights for the common good which he is entitled to enjoy in time of peace. But, sir, the right to control their own government according to constitutional forms is not one of the rights that the citizens of this country are called upon to surrender in time of war.FROM THE FLOOR OF THE US SENATE , OCTOBER 6, 1917108W ar changes nations and people in ways unimaginable before hostilities commence. When fighting breaks out, political leaders sometimes feel compelled to suppress dissent because negative comments about the government or its military supposedly embolden the enemy and undermine national morale. Yet the notion of a loyal opposition that dares to speak the truth to power is the hallmark of a republican form of government. Stifling dissent presents a danger to the republic that sometimes equals the threat posed by foreign belligerents. Distinguishing between legitimate criticism and speech that creates a clear and present danger to the safety and security of the regime can be difficult in peacetime. During wartime, the task is complicated by inflamed passions as well as rational and irrational fear of the enemy.The US response to the Great War, as it was called before people knew global conflicts would require numbering, presented a clear example of the damage caused by government responses to fears of foreign elements. The war years were worrisome for many Americans. They watched, horrified, as casualty figures rolled in from across the Atlantic. The European War of 1914 to 1918 was directly or indirectly responsible for 37 million deaths. Of that total, more than one hundred seventeen thousand were Americans. Although the number of American dead paled in comparison to the millions of Europeans who perished, the carnage nonetheless shocked the citizenry. Why had the nation’s solders paid so high a price? Surely muddy, blood-soaked acreage in Belgium, France, and Germany was not worth the lives of a generation of young men who did not even live on the European continent.109 - eBook - ePub

Attacks on the American Press

A Documentary and Reference Guide

- Jessica Roberts, Adam Maksl(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

1 THREATS TO THE PRESS DURING WARTIMEPassage contains an image

“Scandalous and Malicious Writing or Writings against the Government of the United States”DOCUMENT An Act in Addition to the Act, Entitled “An Act for the Punishment of Certain Crimes Against the United States.”•Document 1: The Sedition Act of 1798•Date: July 14, 1798•Where: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania•Significance: Passed narrowly by Congress under Federalist control in 1798, the law permitted the government to punish speech seen as critical of the federal government, the president, or Congress. The act, which was allowed to expire fewer than three years after its passage, was criticized as being unconstitutional. Though never directly tested before the Supreme Court, the highest court issued several other rulings in the twentieth century indicating that the short-lived law would likely run afoul of the rights guaranteed by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.SECTION 1. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, That if any persons shall unlawfully combine or conspire together, with intent to oppose any measure or measures of the government of the United States, which are or shall be directed by proper authority, or to impede the operation of any law of the United States, or to intimidate or prevent any person holding a place or office in or under the government of the United States, from undertaking, performing or executing his trust or duty, and if any person or persons, with intent as aforesaid, shall counsel, advise or attempt to procure any insurrection, riot, unlawful assembly, or combination, whether such conspiracy, threatening, counsel, advice, or attempt shall have the proposed effect or not, he or they shall be deemed guilty of a high misdemeanor, and on conviction, before any court of the United States having jurisdiction thereof, shall be punished by a fine not exceeding five thousand dollars, and by imprisonment during a term not less than six months nor exceeding five years; and further, at the discretion of the court may be holden to find sureties for his good behaviour in such sum, and for such time, as the said court may direct. - eBook - PDF

Free Speech, The People's Darling Privilege

Struggles for Freedom of Expression in American History

- Michael Kent Curtis, Neal Devins, Mark A. Graber, Neal Devins, Mark A. Graber(Authors)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- Duke University Press Books(Publisher)

In short, the case of the Sedition Act brilliantly illuminates the essen-tially antidemocratic nature of the e ff ort to protect the institution of slavery from criticism. It does the same, of course, for the e ff ort to silence critics of the government’s policy during the Civil War. The Sedition Act is central to the free speech struggles recounted in this book in still another way. The attack on the act emphasized two themes—freedom of speech and protection of states’ rights. Many crit-ics of the act appealed to states’ rights in an e ff ort to protect free speech, much as today consumer advocate Ralph Nader appeals to states’ rights against federal laws that restrict state common law or statutory rights to sue makers of defective products. As slavery became the main political the debate over the sedition act [ 55 ] issue agitating the nation, the tension between the idea of free speech as (potentially, at least) merely a limit on the national government and the idea that free speech was essential to representative government became increasingly clear. Both the Sedition Act and the battle for free speech about slavery are chapters in the growth of the idea that democratic gov-ernment for the United States required national constitutional protec-tion for free speech: a protection that limited the states as well as the na-tional government and that allowed broad protection for discussion of public a ff airs. For all these reasons, the Sedition Act, to which I now turn, is an im-portant part of our free speech story. This chapter discusses the legisla-tive struggles over the framing of the act and the public debate the act engendered. Chapter will explore the act’s enforcement and theories of free speech that followed it. From the Revolution to the Bill of Rights In the Sedition Act debate, in the debate over antislavery speech, and in the debate over antiwar speech, ideas of popular sovereignty were cru-cial. - eBook - PDF

Discourses of Freedom of Speech

From the Enactment of the Bill of Rights to the Sedition Act of 1918

- J. Rudanko(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

In brief, the Sedition Act probably constituted the most serious actual and conceptual threat to freedom of speech that has materialized to 5 Freedom of Speech under Threat: The Sedition Act of 1798 The Sedition Act of 1798 73 this day. It is therefore important to any investigation dealing with the emergence of the American conception of freedom of speech. The Sedition Act was pushed through by Federalists against fierce Republican opposition in the House of Representatives in early July 1798. It was signed into law by President Adams on July 14, 1798. The purpose of this chapter is to examine the rhetoric that Federalists used to justify the Act and the rhetoric that was used by Republicans to oppose it. - eBook - ePub

Legislative Deliberative Democracy

Debating Acts Restricting Freedom of Speech during War

- Avichai Levit(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The Creation of the Media: Political Origins of Modern Communications . New York: Basic Books, 2004.Statutes at Large of the United States of America , Vol. 40, Part 1. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1919.Stone, Geoffrey R. Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime from the Sedition Act of 1798 to the War on Terrorism . New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2004.Zinn, Howard. A People’s History of the United States: From 1492 to the Present . 2nd ed. London: Longman, 1996.Passage contains an image

3 Congressional Deliberation on the Espionage and Sedition Acts

We all have our heart and soul in this war, but because we have our heart in it is no reason why we should lose our head. It is our patriotic duty to remain calm, cool, and deliberate. Representative Fiorello Henry LaGuardia, May 2, 1917Senators, in times of war people grow hysterical…even legislative bodies, are not exempt from the contagion of hysteria. It is better to move along slowly; it is better to deliberate. Senator Thomas Hardwick, April 5, 1918The Espionage Act

As mentioned earlier, the Espionage Act does in fact deal mostly with issues of espionage and the protection of military secrets, while two parts – one concerning making statements to cause insubordination or obstruct recruiting (title I, section 3), and the other on nonmailability (Title XII) – restrict freedom of speech when the United States is at war. The original bill included an additional provision, relating to censorship of the press; however, after deliberating the bill, with extensive debate on the censorship provision, Congress made various amendments and also stroke out the censorship provision.In what follows, I analyze the House Judiciary Committee hearings on the Espionage Act, and the deliberation on the floor, that is, the exchange of information and arguments, including framing arguments in terms of the public good and persuasion.1House Judiciary Committee Hearings and Deliberation

In the case of the Espionage bill, the House Judiciary Committee conducted public hearings and heard oral testimonies. External individuals and groups appeared before the committee and articulated views concerning the proposed legislation restricting freedom of speech, and the executive offered written review. As a result, the original draft of the law was amended. - eBook - ePub

Sedition and the Advocacy of Violence

Free Speech and Counter-Terrorism

- Sarah Sorial(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

UNSW Law Journal, 28, 3: 868–86.6 Howard, J., Prime Minister, ‘Counter-terrorism laws strengthened’ (press release, 8 September 2005) in Australian Law Reform Commission, ‘Origins and history of sedition law’, para 2.49.7 Hansard HC vol 438 col 334 (26 October 2005).8 Alien Act (ch 58) 1 Stat 570 (1798).9 See Donohue, L. K. (2005–6) ‘Terrorist speech and the future of free expression’, Cardozo Law Review 27: 233–341 for an excellent and comprehensive historical account of sedition laws in the United States.10 Espionage Act of 15 June 1917 (ch 30) tit I s 3, 40 Stat 217, 219.11 Sedition Act (ch 75) s 3, 40 Stat 553 (1918).12 Schenck v United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919).13 Frohwerk v United States, 249 U.S. 204 (1919).14 Debs v United States, 249 U.S. 211 (1919).15 Gitlow v People of New York, 268 U.S. 652 (1925).16 Bridges v California, 314 U.S. 252, 263 (1941).17 The Smith Act 18 U.S.C. #2385 (1994).18 Dennis v United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951).19 Brandenburg v Ohio, 395 U.S. (1969) at 449.20 Hess v Indiana, 414 U.S. 105 (1973). In this case, the court reversed a conviction of disorderly conduct of a demonstrator on the grounds that the words did not indicate an intention to produce imminent lawless conduct.21 People v Upshaw, 741 NYS 2d 664 (2002).22 ‘No charges against Bin Laden supporter’, NYLJ 6 (26 April 2002).23 While the CPA had not had much success at the polls, it did have considerable power within the trade union movement during this early Cold War period. Consequently, there was a push to outlaw the CPA on the basis that it was a subversive instrument of the USSR. Between 1920 and 1950, the Commonwealth passed a number of Acts and made several regulations in order to deal with the alleged threat posed by the CPA such as the War Precautions Repeal Act 1920 (Cth) s 12; Crimes (Amendment) Act 1926 (Cth); Crimes (Amendment) Act 1932 (Cth); National Security (Subversive Associations) Regulations 1940 (Cth); Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950 (Cth). For a comprehensive examination of this history, see Douglas, R. (2002) ‘Saving Australia from sedition: Customs, the Attorney-General’s department and the administration of peacetime political censorship’, Federal Law Review - eBook - ePub

Unreliable Watchdog

The News Media and U.S. Foreign Policy

- Ted Galen Carpenter(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Cato Institute(Publisher)

Sometimes the government’s campaign against troublesome dissidents goes beyond trying to cut off general, iconoclastic foreign policy dissent. Officials instead seek to bar stories that expose specific cases of policy blunders or malfeasance, even if the critics in question did not necessarily oppose the overall thrust of Washington’s global policy. Indeed, administrations have even attempted to suppress articles that merely had the potential to cause them embarrassment or political difficulties. Officials invariably portray such moves as necessary to prevent the exposure of classified information that could badly damage the nation’s security. All too often, though, those justifications appear to be cynical excuses that conceal far less savory motives.The track record of censorship, prosecution for espionage or sedition, and other coercive tactics directed against uncooperative journalists is long. Censorship, especially battlefield censorship, was a ubiquitous practice in both the Union and the Confederacy during the Civil War.1 That pattern resurfaced during both world wars once the United States became a belligerent. As discussed in Chapter 1 , although the government preferred to seduce the press and use journalists as propaganda agents during the two world wars, it always kept an iron fist inside its velvet glove.The Espionage Act of 1917 empowered the postmaster general to deny use of the mail to any publication that, in his sole judgment, advocated insurrection, treason, or resistance to the laws of the United States. Postmaster General Albert Burleson, Woodrow Wilson’s appointee and a staunch pro-war loyalist, adopted an extremely broad interpretation of those provisions. He used his new powers to exclude a wide array of newspapers, magazines, and pamphlets that exhibited any hint of pacifist or “isolationist” sentiments. Even if a paper avoided publishing an “illegal idea”—an absurdly vague standard—it could be barred from the mail for betraying, in the words of one postal censor, “an audible undertone of disloyalty” in ostensibly legal comments.2Federal prosecutors during World War I considered the mere circulation of anti-war pamphlets or articles a violation of the Espionage Act. Wilson’s administration was notoriously thin-skinned about any criticism of its war effort. Dozens of anti-war pacifists and socialists in the press went to prison during the war, and most of them (along with other critics imprisoned under the Espionage Act)—did not gain their freedom until President Warren Harding took office in March 1921—nearly two and a half years after the Armistice ended the fighting in November 1918. - eBook - PDF

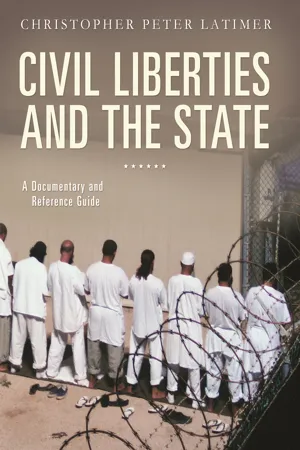

Civil Liberties and the State

A Documentary and Reference Guide

- Christopher Peter Latimer(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

The statute of 1917 punishes conspiracies to obstruct as well as actual obstruction. If the act, (speaking, or circulating a paper,) its tendency and the intent with which it is done are the same, we perceive no ground for saying that success alone warrants making the act a crime. . . . Judgments Affirmed. SOURCE: http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/cgi-bin/getcase.pl?court=US&vol=249&invol=47 ANALYSIS The Supreme Court has never held that freedoms of speech, press, and assem- bly are completely without limits. During World War I, Schenck mailed circulars to draftees. The circulars suggested that the draft was a monstrous wrong motivated by the capitalist system. The circulars urged “Do not submit to intimidation” but advised only peaceful action such as petitioning to repeal the Conscription Act. Schenck was charged with conspiracy to violate the Espionage Act by attempting to cause insubordination in the military and to obstruct recruitment. The Court upheld the Espionage Act of 1917 and concluded that the defendant did not have a First Amendment right to free speech against the draft during World War I. One of the primary difficulties for the majority was settling on a general stan- dard to be applied in determining when a form of expression becomes so threaten- ing to society that it deserves no constitutional protection and must be controlled by government. The clear and present danger test effectively established a doctrine that allowed the government to suppress political speech under certain circumstances such as wartime. Holmes admitted that in peacetime Schenck’s words would have been protected by the Constitution. The decision, in addition to sending Schenck to jail for six months, resulted in a pragmatic “balancing test” allowing the Supreme Chapter 4 • 20th-Century Court Rulings 221 Court to assess free speech challenges against the state’s interests on a case-by-case basis. - eBook - ePub

Language, Symbols, and the Media

Communication in the Aftermath of the World Trade Center Attack

- Robert E., Jr. Denton(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Whether provoked or not, the North Vietnamese attack on American naval ships in the Gulf of Tonkin in August, 1964 gave President Lyndon Johnson an excuse to ask Congress for broader military power. After that he felt more secure in attacking the news media. When Johnson discovered that the film used by CBS of a U.S. soldier setting a fire to a peasant shack in Southeast Asia was a re-enactment, Johnson called on J. Edgar Hoover to begin an FBI investigation of Morley Safer, the reporter responsible (Small 1988, 65). Draft card burners were prosecuted; Martin Luther King suffered from rumors circulated by the administration that communists had infiltrated into the core of his organization (Small 1988, 100).During the same war, President Nixon’s monitoring and attempted intimidation of the press became legendary. For example, in 1972 the CIA initiated “Project Mudhen,” to spy on columnist Jack Anderson and his staff (Spear 1984, 136). The executive branch also focused on such liberal reporters as Daniel Schorr and Cassie Mackin.The Congress

The Congress, as we have seen in the current crisis, often follows the lead of the president. However, the Congress has also taken the lead in initiating restrictive legislation. That was certainly the case during the Alien and Sedition crisis, when Federalists under the direction of Hamilton produced an ambitious legislative package that resulted in the passage of the following laws: The Naturalization Act forbade aliens from being admitted to citizenship unless they had has resided in the United States for at least fourteen years. No native, citizen, subject, or resident of a country with which the United States was at war could be admitted to citizenship. The Alien Act allowed the president to order all aliens that he judged to be dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States to depart. The Alien Enemies Act held that when war is declared or invasion threatened, all natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of the hostile nation, being males of the age of fourteen years and upwards, who shall be within the United States, and not actually naturalized, shall be liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and removed, as alien enemies.12

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.