History

Totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a political system in which the state holds total authority over society and seeks to control all aspects of public and private life. It is characterized by a single-party dictatorship, strict censorship, and the suppression of opposition. Totalitarian regimes often use propaganda and state-controlled media to maintain power and enforce conformity among the population.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Totalitarianism"

- eBook - PDF

Rotten Foundations

The Conceptual Basis of the Marxist-Leninist Regimes of East Germany and Other Countries of the Soviet Bloc

- Peter W. Sperlich(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

It must determine all realms of individual and social existence." Or as Arendt [1958, 456] wrote: "It is in the very nature of totalitarian regimes to demand unlimited power. Such power can only be secured if literally all men, without a single exception, are reliably dominated in every aspect of their life." For similar definitions see Curtis [1969, 59-60], Mampel [1988, 13], and Wolfe [1961, 261-267]. In a totalitarian system, there are no theoretical limits to government meddling, and, in modern times, very few practical ones. Even circus performances become the government's business The Issue of Totalitarianism 145 in a full-fledged totalitarian society. Kolakowski [1981, 3:148-149] re- ported that the Soviet circus had been ideologically reformed in 1949 by an article in PRAVDA which con- demned bourgeois formalism in this domain. There were, it appeared, some per- formers who lapsed into cosmopolitan forms of humour, without ideological content, and tried simply to make people laugh, instead of educating them how to deal with the class enemy. Said Vyshinsky [1948, 76]: "We acknowledge nothing as 'private'." There is no legitimate autonomy (there may be some inadvertent autonomy) in any sphere of life: economic, political, social, or cultural. Totalitarianism is the comprehensive politicization and control of human existence. There are no acts without political significance, and none that are exempted from control. Will Herberg [1968, 131] took a similar per- spective when identifying these three items as the core characteristics of a totalitarian state: (1) it recognizes no majesty beyond itself; (2) it claims jurisdiction over all aspects of life; (3) it refuses to acknowledge any private sphere. - eBook - ePub

- Anthony Giddens(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Polity(Publisher)

The concept is usually taken to be above all a political one, referring to a mode of organizing political power, involving its extreme concentration in pursuit of objectives defined by a narrowly circumscribed leadership. Friedrich’s definition is the one perhaps most often quoted in the literature. Totalitarianism, he says, is distinct ‘from other and older autocracies’ and from ‘Western-type democracies’. It has six characteristics: ‘(1) a totalist ideology; (2) a single party committed to this ideology and usually led by one man, the dictator; (3) a fully developed secret police; and three kinds of monopoly or, more precisely, monopolistic control: namely that of (a) mass communications; (b) operational weapons; (c) all organisations, including economic ones.’ 4 The contrast between Totalitarianism and ‘Western-type democracies’ is of key importance in explaining the popularity of the concept in the period since the Second World War. Totalitarian states were regarded by liberal political observers as including those forms of social order that have an advanced industrial base, but do not display the institutional characteristics of liberal democracy. Whereas when referring to Italy or Germany Totalitarianism designated a relatively transitory phase in social development – terminated by war – in the case of the Soviet Union and the East European countries it was used to refer to a definite type of socio-political order separate from the capitalist states, continuing as long as that order remained in existence. Applied as a characteristic of the East European states, ‘totalitarian’ refers to a political system supposedly displaying the characteristics mentioned by Friedrich. The USSR and the state socialist societies are portrayed as monolithic systems of political power, founded upon cultural and social conformity deriving from the suppression of interest divisions - eBook - ePub

Totalitarianism

Part Three of The Origins of Totalitarianism

- Hannah Arendt(Author)

- 1968(Publication Date)

- Mariner Books(Publisher)

The struggle for total domination of the total population of the earth, the elimination of every competing nontotalitarian reality, is inherent in the totalitarian regimes themselves; if they do not pursue global rule as their ultimate goal, they are only too likely to lose whatever power they have already seized. Even a single individual can be absolutely and reliably dominated only under global totalitarian conditions. Ascendancy to power therefore means primarily the establishment of official and officially recognized headquarters (or branches in the case of satellite countries) for the movement and the acquisition of a kind of laboratory in which to carry out the experiment with or rather against reality, the experiment in organizing a people for ultimate purposes which disregard individuality as well as nationality, under conditions which are admittedly not perfect but are sufficient for important partial results. Totalitarianism in power uses the state administration for its long-range goal of world conquest and for the direction of the branches of the movement; it establishes the secret police as the executors and guardians of its domestic experiment in constantly transforming reality into fiction; and it finally erects concentration camps as special laboratories to carry through its experiment in total domination.I: The So-called Totalitarian State

HISTORY TEACHES THAT rise to power and responsibility affects deeply the nature of revolutionary parties. Experience and common sense were perfectly justified in expecting that Totalitarianism in power would gradually lose its revolutionary momentum and utopian character, that the everyday business of government and the possession of real power would moderate the prepower claims of the movements and gradually destroy the fictitious world of their organizations. It seems, after all, to be in the very nature of things, personal or public, that extreme demands and goals are checked by objective conditions; and reality, taken as a whole, is only to a very small extent determined by the inclination toward fiction of a mass society of atomized individuals.Many of the errors of the nontotalitarian world in its diplomatic dealings with totalitarian governments (the most conspicuous ones being confidence in the Munich pact with Hitler and the Yalta agreements with Stalin) can clearly be traced to an experience and a common sense which suddenly proved to have lost its grasp on reality. Contrary to all expectations, important concessions and greatly heightened international prestige did not help to reintegrate the totalitarian countries into the comity of nations or induce them to abandon their lying complaint that the whole world had solidly lined up against them. And far from preventing this, diplomatic victories clearly precipitated their recourse to the instruments of violence and resulted in all instances in increased hostility against the powers that had shown themselves willing to compromise. - eBook - PDF

- Karin A. Fry(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Continuum(Publisher)

However, while she spends the bulk of the book describing a socio-logical history of the conditions leading up to Totalitarianism, the overall significance of Arendt’s book has largely to do with the por-tions that describe Totalitarianism itself. Totalitarianism Hannah Arendt believes that Totalitarianism is a new type of politi-cal formation that is unprecedented and differs from other kinds of political tyrannies. In fact, Arendt thinks that Totalitarianism defies comparison because it explodes the traditional Western concepts of politics and government and calls for new ways of understanding ( EU 339). In order to describe Totalitarianism, Arendt makes some distinctions between Totalitarianism and other forms of political tyr-anny or despotisms. The first difference between Totalitarianism and tyranny is that typical political tyrannies invade other countries in order to gain material goods and land to increase the power of the tyrannical ruler. In tyrannies, people are dominated because of the self-interest of the ruler or group who seek to amass their power. Totalitarian regimes similarly involve a strong ruler like tyrannies, but the ruler does not primarily seek personal and selfish acclaim Totalitarianism AND THE BANALITY OF EVIL 17 and power. In Totalitarianism, invasion occurs primarily to promote the ideology of the regime, rather than the personal gain of the ruler. In the case of Nazism, this ideology concerns a racist dogma promot-ing the prominence of the Aryan race, while for Stalinism, the ideology concerns the need to eradicate capitalism and the bourgeoisie. The totalitarian ruler promotes the ideology of the government and justi-fies all actions according to it, even at the expense of the resources of the regime or the nation. - eBook - PDF

Totalitarianism

A Borderline Idea in Political Philosophy

- Simona Forti(Author)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- Stanford University Press(Publisher)

Nazi to- talitarianism is not the continuation, although paroxysmal, of that political tradition revolving around the notion of state. It destroyed basic European judicial construction. Franz Neumann’s representation of Nazi Totalitarianism also contests the solid image of Nazism as a political system of order. Neumann does not provide a definition of what totalitarian is, but he often employs the concept to characterize any system that tends to be omnipotent and all- encompassing, thereby combining authoritarianism and monopolistic capitalism. His eminently political reading of Hitlerism, however, is as “heterodox” as Fraenkel’s. Often portrayed as a “polycentric disorder,” a How the Concept “Totalitarianism” Came to Be 28 Behemoth (F. Neumann 2009) rather than a Leviathan—the Hobbesian sea monster and symbol of civil war against an earthly God who stood for state order—Totalitarianism nourishes itself not only with external but also with internal disorder. In a nutshell, Totalitarianism is nothing but a disorder created by the overlapping of various centers of power—party, bureaucracy, army, big industry—which, in turn, multiply and overlap further so that the führer emerges as the sole arbiter among the chaos. In the seminal 1942 Permanent Revolution, Sigmund Neumann also fosters the idea that Totalitarianism eventually releases chaos rather than order. As war originates, totalitarian regimes, whether Nazi or Stalinist, are also their essential engine. “A constant state of war is the natural climate of totalitarian dictatorship,” for it brings permanent dynamics that cannot be stopped without stopping everything (S. Neumann 1942, xi). If they want to survive, totalitarian regimes must make an utterly artificial revolution perpetual. This is what distinguishes such dictatorships from past ones. - eBook - ePub

Totalitarianism and Political Religions, Volume 1

Concepts for the Comparison of Dictatorships

- Hans Maier(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

It is remarkable that those who were forced to live under such regimes continually apply the concept of Totalitarianism to articulate their experiences (specifically, their experiences until shortly before 1989 and by no means only those of the Stalin era). They do so, moreover, with complete awareness. Whoever emphasized earlier how important it is to begin with the regime’s official self-understanding and to measure it in terms of its own goals should, in his assessment today, at least incorporate the self-understanding of those who had to suffer under these regimes; he should not decide the question concerning the relevance of the Totalitarianism approach before he has examined the degree of reflected experience that is expressed in the essays and speeches of someone like Vaclav Havel. The Totalitarianism concept, then, is used by former dissidents—but by no means only by them. And it is not used in order to take sides in a dispute among political scientists, but in order to bring to light the historically new and unique element of some dictatorships of the twentieth century. The claim and instruments of power in these dictatorships were apparently unlimited and excluded no sphere of life. Over and again, they stressed how comprehensive and penetrating—how totalitarian—these systems were. Of this, we find two examples. ‘Totalitarianism’, Karl Jaspers writes, still under the immediate impression of Nazi rule,is neither Communism, nor Fascism, nor National Socialism, but has emerged in all these forms… To see through it is not easy. It is like an apparatus that sets itself in motion, in that the actors themselves often do not know it even as they are realizing it… Totalitarianism is like a ghoul that drinks the blood of the living and becomes real through it, while the victims continue their existence as a mass of living corpses.2Less dramatic is Vaclav Havel, who, as president of Czechoslovakia, made a New Year’s Address in 1990 in which he identified a ‘depraved moral atmosphere’ as the worst inheritance of Totalitarianism. He excepted no one from it:I speak of all of us. All of us have grown accustomed to the totalitarian system, have accepted it as an inalterable fact and thus have actually retained it in life. In other words: we are all—even if each in a different measure, of course—responsible for the course of the totalitarian machinery; no one is solely its victim; we are all at once its co-creators.3 - eBook - PDF

Modernism and Totalitarianism

Rethinking the Intellectual Sources of Nazism and Stalinism, 1945 to the Present

- R. Shorten(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

Yet, if the discussion earlier of the restricted scope of classical Totalitarianism – excluding Italy – is persuasive (that, properly speaking, the state as end-in-itself does not even match totalitarian- ism in theory) – it should be of even less consequence that complete domination by the state should not match practice. Accordingly, the corollary is not that Totalitarianism should be jettisoned as a conceptual resource: it is still logically consistent to claim that the totalitarian thesis identifies a very real political inno- vation that, in the twentieth century, constituted a decisive departure from both democracy and authori- tarianism. Rather, the corollary is that ‘Totalitarianism’ ought to be rethought in the aspect of its chief defini- tional properties. Where, then, do the distinguishing features of (this) Totalitarianism reside? It is a bad mistake, once having pulled apart three types of political regime, to advert to methods of rule as a chief definitional property of Totalitarianism. It was only after the collapse in 50 Modernism and Totalitarianism confidence in Friedrich and Brzezinski’s six-point syn- drome that Totalitarianism defined by total control came to be regarded with circumspection. However, prior to that, the structural model was always out of step with operative moral intuitions – intuitions that continue into the present, and which continue with good reason. This intuition is that, at base, what justifies the addition of a new word to the political lexicon is the experience of political mass murder, being sponsored by the leadership of a modern state, and being exceptional in both intention and scale. 70 Furthermore, it is an intuition that picks out the particular moral significance of Koestler’s fourth ele- ment of Totalitarianism, the experiment in reshaping humanity, and elevates an aspect of it to the place of core definitional criterion; namely, the physi- cal destruction of ideologically specified opponents. - eBook - PDF

Fascination with the Persecutor

George L. Mosse and the Catastrophe of Modern Man

- Emilio Gentile, John Tedeschi, Anne Tedeschi, John Tedeschi, Anne Tedeschi(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- University of Wisconsin Press(Publisher)

But in reality it disguises the differences. There is a big difference between Lenin, Stalin and Hitler. There is a big difference between Bolshevism and Fascism. 5 Mosse repeated this negative judgment on other occasions as well. Such views, although acceptable as a critique of theories of Totalitarianism that 38 The Road to Totalitarianism cancel out in a single and static model the historical characteristics of com- munism, fascism, and National Socialism, however, have the negative effect of obscuring the importance that the problem of Totalitarianism has had in his interpretation of European culture. Mosse had occupied himself with the question of Totalitarianism as far back as the 1950s, in his lectures as well as in his writings, reaching the point of working out, even if unsystemati- cally, his own interpretation of the phenomenon as the result of ideas and attitudes present in European history from the time of the French Revolu- tion. For example, discussing Jacobinism in a course during the 1955–1956 academic year, Mosse dwelt on the concept of “totalitarian democracy,” which had been introduced by Jacob Talmon three years earlier, although without mentioning the Israeli scholar by name. Referring to the subject of the Jacobin Terror, Mosse said: Bear in mind what I have said; it is the experiment which still divides French- men in their judgment of it and adds a second thing: it is a model for what has been called “totalitarian democracy” or what today in the East are called “popular democracies.” . . . Yet this totalitarian democracy was not a rejec- tion of the eighteenth-century individualism—but rather the result of a too perfectionist attitude toward these values. It made man the center of all refer- ence: man was the kind of idealized rational and moral animal the philosophes had believed in. This meant: 1. Man had to be brought to a common denom- inator. All regional differences, or group differences had to be eliminated. - Alessandra Tarquini, Marissa Gemma(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- University of Wisconsin Press(Publisher)

4 R The Ideology of the Totalitarian State Myth and Ideology As we observed in chapter 1, for many years most Italian scholars denied the existence of a fascist ideology, reducing fascism to a purely practical phe- nomenon. As evidence for this claim, many historians pointed to the fact that the regime proved incapable of producing its own doctrine comparable in coherence and solidity to those of the great political traditions, from lib- eralism to democracy, from socialism to communism. Furthermore, they argued, during the twenty years in which Italy was transformed into a total- itarian state, fascism managed to formulate a series of heterogeneous ideo- logical positions. Reactionary and modernist, Catholic and atheist, nationalist and statist, corporatist and syndicalist, the ideologies of fascism would ulti- mately give rise to that “political and cultural machine” that Sergio Luz- zatto in 1999 called “a bazaar.” 1 As we have seen, many American historians concurred with this interpretation. Jeffrey Schnapp, for instance, claimed that the weakness of fascist ideology engendered the regime’s massive aes- thetic output, as it tried to use propaganda to compensate for the absence of a coherent ideology. Other historians have argued, instead, that the issue had to be addressed by first clarifying what the term ideology means. In this vein, David D. Roberts wrote that if ideology is understood as synony- mous with political doctrine, with an emphasis on its systematic nature, then one is forced to conclude that fascism did not have an ideology. On the other hand, if we understand ideology as a collection of visions, values, and ideals, then one must conclude not only that fascism expressed its own 73 74 The Ideology of the Totalitarian State ideology, but that this ideology was definitely capable of guiding political action. 2 Ever since the appearance of the term ideology in the late eighteenth century, a great many interpretations of it have been put forth.- eBook - PDF

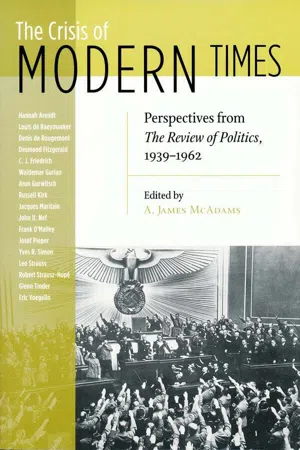

Crisis of Modern Times

Perspectives from The Review of Politics, 1939-1962

- A. James McAdams(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- University of Notre Dame Press(Publisher)

The third part—on Totalitarianism— contains studies on the classless society that results from general superfluity of the members of a society, on the difference between mob and mass, on totalitarian propaganda, on totalitarian police, and the con-centration camps. The digest of this enormous material, well documented with footnotes and bibliographies, is sometimes broad, betraying the joy of skilful narration by the true historian, but still held together by the conceptual discipline of the general thesis. Nevertheless, at this point a note of criticism will have to be allowed. The organization of the book is somewhat less strict than it could be, if the author had availed herself more readily of the theoretical instruments which the present state of science puts at her disposition. Her principle of relevance that orders the variegated materials into a story of Totalitarianism is the disintegration of a civi-lization into masses of human beings without secure economic and social sta-tus; and her materials are relevant in so far as they demonstrate the process of disintegration. Obviously this process is the same that has been categorized by Toynbee as the growth of the internal and external proletariat. It is surprising that the author has not used Toynbee’s highly differentiated concepts; and that even his name appears neither in the footnotes, nor in the bibliography, nor in the index. The use of Toynbee’s work would have substantially added to the weight of Arendt’s analysis. This excellent book, as we have indicated, is unfortunately marred, however, by certain theoretical defects. The treatment of movements of the totalitarian type on the level of social situations and change, as well as of types of conduct 276 Eric Voegelin determined by them, is apt to endow historical causality with an aura of fatality. Situations and changes, to be sure, require, but they do not determine a response.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.