History

Zanzibar

Zanzibar is an archipelago off the coast of East Africa with a rich history shaped by trade, slavery, and colonialism. It was a major hub for the Indian Ocean trade, particularly in spices and ivory. Zanzibar also played a significant role in the Arab slave trade. The islands eventually became a British protectorate before gaining independence and merging with Tanganyika to form Tanzania.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Zanzibar"

- Sarah Longair(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

45 Glassman also highlights the importance of the generation of Arab intellectuals and teachers who were trained under L. W. Hollingsworth in the new Teacher Training School from 1923. This group reciprocally influenced Hollingsworth and W. H. Ingrams in their research into, and publications about, the history of Zanzibar. This book brings important new evidence to light to build on Glassman’s work by examining how the Museum gave this historical interpretation physical form. It is therefore possible to reposition the Museum’s historical narrative as one that was informed by a locally created concept of history, rather than dictating it.In order to untangle these intersecting ideas of history and to reveal how the Museum was influenced by, and itself influenced, constructions of the past, it is necessary to outline the broader history of Zanzibar and some of the key historiographical interpretations.Pre-Protectorate History

The history of Zanzibar can be best understood by considering its participation in Indian Ocean trading networks. People, objects and ideas had circulated through this oceanic space for millennia. The earliest references to the island in western literature are found in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea , which describes a vast network of trade and commerce around the Indian Ocean.46 The island of Men(o)uthias mentioned in this Greek guide to navigation and trading opportunities has been identified with Unguja.47 The twice-yearly monsoon winds enabled traders from the Indian Ocean rim to circulate and exchange their goods, laying the foundations of the islands’ cosmopolitan coastal culture. This sophisticated mercantile population, which would become known as the Swahili, developed along the East African coast. Islam gradually became established as the dominant coastal religion with waves of immigrants from Arabia and the Persian Gulf.48 Archaeological finds and ruins of sizeable towns along the coast testify to the prosperity and extent of the Swahili city-states. The development of this network of Swahili coastal states was known for much of the period in question as the ‘Zenj Empire’, tying its development closely to influence from Arabia, through the arrival of the fabled ‘Shirazi’ princes from Persia. Archaeological research in the post-colonial era has uncovered evidence from the first millennia of trading towns on the coast established by Bantu- and Cushitic-speaking communities settling on the coast.49- eBook - PDF

Where Humans and Spirits Meet

The Politics of Rituals and Identified Spirits in Zanzibar

- Kjersti Larsen(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Berghahn Books(Publisher)

2 I NTRODUCTION TO Z ANZIBAR : THE PLACE , ITS POLITICS AND ORGANIZATION I will in the following chapter give a brief introduction to Zanzibar and Zanzibar Town and to the historical and social processes which are relevant in this context. I shall stress the underpinning importance of ideas of kabila and gender in this society – ideas which are closely tied to the conceptualization of difference and thus, to the distinction between self and other. But let me start with Zanzibar as a place. Zanzibar forms part of the wider Swahili coast, which runs from southern Somalia to northern Mozambique. 1 Situated in the Indian Ocean about 40 km from the Tanzanian mainland, Zanzibar is a semi-autonomous polity in the United Republic of Tanzania that consists of two main islands – Unguja, with a population close to 650,000, and Pemba, with a population of 350,000 – and some smaller islands, the biggest among them being Tumbatu. 2 Zanzibar Town, with a population of about 200,000, is situated on the island of Unguja. It is divided into Ng’ambo and Mji Mkongwe or Stone Town, which used to be the seat of the former Sultan of Zanzibar. Stone Town stands on a peninsula; most of the lagoon was filled in many years ago, so that only a creek separates Stone Town from the main body of the island. Today Stone Town is cut off from the main body of the island by wider asphalt roads and relatively heavy traffic. Ng’ambo stretches out in a wide radius on the other side of the creek or, rather, the road. When in Zanzibar, I have lived in Ng’ambo – in a neighbourhood called Vikokotoni. Most of Zanzibar Town’s inhabitants live in Ng’ambo – only about 15,000 live in Stone Town itself. Stone Town was previously mainly inhabited by wealthy people of Arab and Indian decent, while Ng’ambo, meaning ‘the other side of the Stone Town’ was to a large extent inhabited by people of African descent, but who were not necessarily poor. - eBook - ePub

Disputing Discipline

Child Protection, Punishment, and Piety in Zanzibar Schools

- Franziska Fay(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Rutgers University Press(Publisher)

Yet I was repeatedly told statements like this one by Amal, a young social worker in her twenties: “There is no space for ‘tribes’ (makabila) today, because Zanzibar does not have any.” Another local female aid worker, possibly in her forties, supported this view, telling me that “people follow culture (utamaduni) here, but there are no ethnic groups. Over the years people have mixed (wamechanganya), so you cannot differentiate between them” (kuwatenganisha). The extraordinary complexity of Zanzibar as neither exclusively “African, Arabian or Indian but partaking of each of these” (Parkin 1995, 201) influences its imagined geographical placement. As a non-African development worker told me, “Zanzibar isn’t Africa; it’s the Arab world in Africa.” Although Zanzibar is of course part of Africa, this trope implies that additional geographical and ideological categorizations may better describe the archipelago. In fact, I often encountered statements that Zanzibar was more like Middle Eastern and Arab states than continental African countries or even mainland Tanzania. Because of Zanzibar’s past as “an Arab colonial state” (Middleton and Campbell 1965, 1), Swahili identity today entails multiple categories that range from mixed African and Arab descent to living primarily in urban areas and speaking Swahili (Fair 2001, 30). Thus, Swahili speakers may simultaneously identify as African and/or Arab, Persian, or Indian (Glassman 2011, 4f). This nonstatic Swahili identity embodies an ongoing social process that makes Swahili society “the epitome of ethnic fluidity and racial indeterminacy” (Glassman 2011, 4f; Eastman 1971). Swahili people have always been perceived as a fluid population and never claimed one cohesive ethnic identity (Ntarangwi 2003, 47; Fair 2001, 31). Swahili worldviews have been described as plural and shifting and reflect the cosmopolitan nature of many Indian Ocean societies (Kresse and Simpson 2009; Loimeier and Seesemann 2006, 1) - eBook - ePub

- Lydia Wilson Marshall(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

In addition to these mercantile houses, Pangani maintains an area of open parkland within the town called Unwajawa Jamhuri, which translates as Freedom Ground or Independence Ground. Many local people identify this site as the location of a nineteenth century slave market. Such a function is difficult to ascertain from an archaeological perspective. Markets often leave little material evidence, being as they are simply a social agreement to meet to exchange goods. What is nonetheless clear is that the naming of the park and its associated folk history likely reflect more about the nature of postcolonial identities in Pangani than actual historical activity. This is not to deny the history of slave trading at Pangani. Instead, I want to suggest that those forces that propel certain sites to being places of memory for the slave trade extend far beyond archaeologically quantifiable or historically specific facts. Rather, how East Africans remember slavery is refracted through all that came after emancipation, both in the colonial era and after national independence.Slavery and its presentation on the island of Zanzibar

The first recorded European to go to Zanzibar (locally known as Unguja) was Vasco de Gama in 1499. It was soon after this that the Portuguese began to take control of the western Indian Ocean maritime trade network with the construction of a series of forts along the mainland coast: Mozambique in 1500, Kilwa Kisiwani and Mombasa in 1505, and Malindi in 1509 (Pearson 2003). Zanzibar was attacked by the Portuguese twice and was eventually taken in 1509; subsequently, a fortified trading post was constructed in Zanzibar's Stone Town (Horton and Clark 1985; Juma 2004). Portuguese control was to be relatively short lived; in 1652 the European settlements on Unguja and Pemba were destroyed by local residents who then turned to the Yarubi dynasty in Oman for support. The Yarubi had historically stood in opposition to the Portuguese, leading an uprising in Muscat, Oman in 1650. In 1698, Portuguese control in the East African region ended with Yarubi victories at Mombasa and Zanzibar (Berg 1968).The establishment of Arab control created a security and stability in the region that was to last until the arrival of nineteenth-century European colonialists. The material result of this stability was the flourishing of a plantation economy and an urbanized mercantile elite with distinct architectural forms of expression with direct links to Oman, such as the aforementioned house styles at Pangani (see also Rhodes, Breen, and Forsythe 2015 for a discussion of the development of palace architecture). By contrast, the vast majority of regular Zanzibari people lived in much more insubstantial houses. As nineteenthcentury accounts show: - Derek R. Peterson(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Ohio University Press(Publisher)

But the connections are plainly there, and reconstructing You are reading copyrighted material published by Ohio University Press/Swallow Press. Unauthorized posting, copying, or distributing of this work except as permitted under U.S. copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. 176 JonA thon glAssMAn them provides an opportunity for confronting the complex nature of intellectual discourse in the colonial world, in particular for examin-ing how historical memories of slavery were constructed and the role those constructed memories played in shaping popular subjectivities, sometimes in profound ways. A M onument to Abolition There is perhaps no better place to listen for the echoes of abolitionism than Zanzibar, a pair of islands just off the East African coast, which since the 1870 s has been emblematic of the African slave trade and Brit-ain’s civilizing mission to end it. Early in the nineteenth century Arab princes from Oman established a sultanate in Zanzibar, which subse-quently became a hub of international trade linking the Swahili coast to markets and ideas from deep in the continental interior and across the western Indian Ocean, Islamic Middle East, and North Atlantic. Zanzibar Town soon became a bustling metropolis, hosting merchants and visitors from throughout the world. Among them were American and European merchants and a steady stream of Western visitors, many of the latter passing on their way to or from India or (after the opening of the Suez Canal) southern Africa. Westerners found the sultanate an exotic anachronism, an oriental despotism that managed to linger even while engaged directly with the forces of Western-influenced commer-cial progress. For many, those backward qualities were best represented by the ruling elite’s continuing addiction to slavery, after even the retrograde plantocrats of the U.S.- eBook - PDF

Zanzibar

Background to Revolution

- Michael F. Lofchie(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

On the basis of these towns and of the continuous presence of the caravans, the Sultan claimed to exercise sovereignty over most of contemporary East Africa. It is doubtful that the Sultan's military power extended be- yond the borders of the towns and there was never a continuous effective Arab occupation of the vast areas outside the towns. But the fact remains that for more than a generation Zanzibar was the imperial power dominant over hundreds of thousands of square miles of East African territory. C H A P T E R I I British Colonial Policy in Zanzibar The essentially autocratic nature of British colonial rule had much to do with enabling the Arab oligarchy to preserve its dominant political status. Zanzibar be- came, like other colonial territories during the era of British overlordship, an administrative state with ulti- mate control in the hands of British officials. The basic functions of government—the formulation and execu- tion of policy, and the maintenance of law and order— were conducted by a disinterested efficient bureaucracy, unanswerable to local opinion. Since this sort of admin- istration did not allow for the free competitive play of opposed political forces, there was very little opportu- nity for Africans to challenge either the overall frame- work of colonial rule or the special political position of the Arab elite.' Moreover, by systematically according Arabs preferential treatment for legislative and admin- istrative positions as well as by preventing other com- munities from effectively challenging the Arabs' pre- eminent position, the colonial government had an ex- tremely conservative stabilizing effect on the political and social structure of the country. Thus, British colo- nial policies not only preserved the Arab community's status as an economic and political elite, but they also endowed the entire racial pattern of stratification with a remarkable degree of continuity. - eBook - PDF

The Roots of Ethnic Conflict in Africa

From Grievance to Violence

- Wanjala S. Nasong'o(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

Political, economic, and social/cultural grievances have been traded among the Arab, African, Shirazi, and other ethnic groups on the islands over a long course of confrontation and are politicized by leading political parties. The 1964 revolution was the climax of the tensions generated by inherent internal contradictions within the Zanzibar community. The revolution wrought into existence a second level of tensions that developed between Zanzibar and Tanganyika. This was caused by the In Search of a Political Identity O 153 creation of the union. The union has become a major political grievance by Zanzibar against mainland Tanzania over matters of autonomy but has also become a forum in which ethnic/racial and regional politics within Zanzibar are contested. Mainland Tanzania, as a patrimonial figure of the union, patronizes those politics and has largely determined their out- come. While internal tensions along ethnic lines have been intermittent, discontentment over the union remains the most sustained grievance that may not disappear from Zanzibar’s national politics. If this remains the case, the union issue is likely to be used in politics to rekindle tensions and regionalism in Zanzibar. It is also likely that the key to unlocking any measure of stability within Zanzibar—and to improving relations between Zanzibar and the mainland—lies with the latter’s decision to agree to reviewing the terms of the union in ways that would be favorable to Zanzibar’s national aspirations. Outside of the union, an autonomous Zanzibar could benefit from advantages that accrue from membership in regional blocs such as the East African Federation. But supporters of Zanzibar separatism would rather see a delayed maturation of the East African Federation until problems over the union with mainland Tanza- nia are resolved (Daily News, June 4, 2007). - eBook - PDF

Peace in Zanzibar

Proceedings of the Joint Committee of Religious Leaders in Zanzibar, 20052013

- Arngeir Langås(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Peter Lang Group(Publisher)

108 Fueled by religious and racial rhetoric, the quest for political power was to increase political polarization. Zanzibar between 1957 and 1992 The period between 1957, when multiparty democracy was introduced, and 1992, when it was reintroduced, was characterized by numerous changes. From its later times as a Protectorate, the period includes Zanzibar’s short-lived status as an independent nation, the revolution, and internal and national developments as part of the United Republic of Tanzania. Because the sub-chapter’s focus is on events and developments that impacted on Christian-Muslim relations, church sources have also been consulted. Turbulent times The period from 1957 to 1964 saw political campaigns and elections, and has retrospectively been referred to as zama za siasa. 109 This political liberalization A HISTORICAL INTRODUC TION TO CHRISTIAN - MUSLIM RELATIONS IN Zanzibar | 69 allowed the expression and politicizing of underlying racial and religious tensions that had hitherto been controlled under colonial rule. The period was character- ized by polarization, insecurity, and violence, resulting in a change where “Zanzi- bar went from being a melting pot of cultures to a hotbed of politics,” becoming an example that “diversities become divisions when they are politicized.” 110 Glassman has shown how ZNP represented Zanzibari nationalism, making use of Islam as a unifying factor. The nationalistic propaganda defined those whose loyalty to the Zanzibari nationalist project was suspect as enemies. Mainland- ers, Christians, ‘barbarians,’ and even ‘Zionists’ were thus labelled enemies. 111 The January 1961 election campaign presented the idea of “Zanzibar as a culturally autonomous Islamic state,” where “multi-racial religious solidarity” under the rule of the sultan would unite Zanzibaris against continental Africa and be the basis for independence. - eBook - PDF

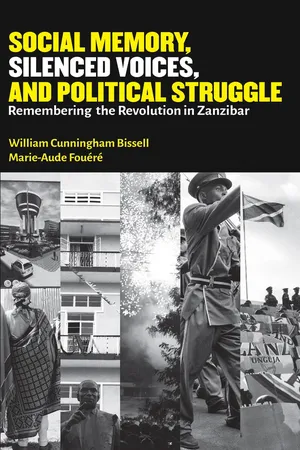

Social Memory, Silenced Voices, and Poli

Remembering the Revolution in Zanzibar

- Cunningham Bissell, Marie-Aude Fouere, Cunningham Bissell, Marie-Aude Fouere(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Mkuki Na Nyota Publishers(Publisher)

Zanzibar is no longer the Zanzibar they remember; it contains only shards of the beautiful landscape they once belonged to. Indeed, al-Riyami concludes the Arabic version of the book with a stark comparison of Zanzibar then and now, which is an ideal way to summarize some of the themes of this essay. 26 Al-Riyami contrasts the old neighborhood of Forodhani, where the police band used to play classical music and symphonic pieces, with the current Forodhani, whose former prestige and splendor have departed, to be replaced by Maasai and other mainland tribespeople selling their “African idols.” Zanzibar, he claims, has gone from a developed nation to an “underdeveloped and impoverished” one, declining from the capital of Seyyid Said bin Sultan’s empire to “an obscure country on the world map.” After making this comparison, al-Riyami concludes the Arabic edition of the book on a philosophical note: “It is true what is said, for every age there is a country and a people.” For many in al-Riyami’s generation, Zanzibar has passed from the horizon of political 25 The opposition party CUF boycotted the most recent March 2016 election re-run. 26 The English version’s conclusion, in contrast, is a summary of major points of each chapter. 300 SOCIAL MEMORY, SILENCED VOICES, AND POLITICAL STRUGGLE struggle into the realm of heritage and memory. Their engagement with Zanzibar is ongoing, but there is (at least publicly) an emphasis by some on moving forward and letting go of the past. But without the ability to commemorate those of their family and neighbors who died in Zanzibar, and without the ability to influence the political situation there, many Omani-Zanzibaris will continue to see Zanzibar as a familiar, not yet alien place, tinged with a great and monumental heritage that is slowly passing away under the influence of the mainland. - eBook - PDF

- Jan G. Deutsch, Brigitte Reinwald, Jan G. Deutsch, Brigitte Reinwald(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Klaus Schwarz Verlag(Publisher)

This is probably why early colonial maps showing the ethnic and racial divisions of the town portray a sizeable part of Vuga as a 'Khoja' area, i.e. a predominantly Hindu Indian settlement. How-ever, these classifications were at best imaginative guesswork and do not fit in at all with what is remembered about the original inhabitants of the area. 7 It must be emphasized that since it is impossible to confirm the information on Kassim and his business activities, it has to be taken at face value. 8 On the naming of neighbourhoods in Zanzibar Town, see the instructive article by Myers (1996). Who are the Zanzibari? Newspaper Debates on Dif-ference, 1948-1958 Katrin Bromber WaZanzibari? Wapo! WaZanzibari na Wa-Zanzibara .('Zanzibaris'? They exist! People of 'Zanzibari' origin and people of mainland origin)' (Manager, Zanzibar, 2001) Introduction The blending of key words is a rhetorical device suited to both amusement and critique. By changing the final vowel, the speaker ridicules people from the mainland ( bara ) who have become permanent residents of Zanzibar and call themselves WaZanzibari. The word-game, however, hints at the concept of difference between 'genuine' WaZanzibari and those of bara origin who, and here lies the rub, are entitled to the same rights. Furthermore, it indicates that discussions of identity are generated especially in places of intense cul-tural exchange such as Zanzibar - an important economic and cultural centre in the Indian Ocean region. The discussion itself is rooted in pre-independence debates on 'Zanzibari' citizenship in the various communities of the Sultan of Zanzibar's dominions - Unguja, Pemba, and the coastal strip of Kenya. Regulated for the first time in 1911 by Decree No. 12, conceptualising the 'Zanzibari' was an important element in the intellectual controversy between the two mainstreams of Zan-zibar nationalism - the Zanzibar Nationalist Party (ZNP, 1956) and the Afro-Shirazi Party (ASP, 1957).

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.