History

East India Company

The East India Company was a British trading company established in the 17th century to pursue trade with the East Indies. It eventually expanded its influence and became involved in politics and governance in India. The company played a significant role in the colonization of India and the establishment of British rule in the region.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "East India Company"

- eBook - PDF

Manufacturing Indianness

Nation-Branding and Postcolonial Identity

- Ishita Sinha Roy(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

The East India Company is one of the oldest companies in the world today. The greatest economic entity of its times, it has impeccable pedigree and a truly enviable heritage. […] By the time it was dissolved in 1858, the Company had acquired all the attributes of a sovereign state. The company also developed wider imperial interests. […]. It internationalized the world’s weights and measures. It controlled over half of all international trade, employed over 10% of all Englishmen and 30% of all Scotsmen, ran armies and the world’s largest navy, governed territories and built entire industries and it had its own currency—the only corporation in the world to have its own “Cash”! —Since 1600 (East India Company Store Catalog, 2010) I t seems fitting to begin a chapter about the “manufacturing” of Indianness with a critical look at the recent revival of that colonial institution—the East India Company—that heralded the entry of the British into the sub-continent, and the accompanying convergence of colonial, postcolonial, and neo- colonial/neoliberal histories in the contemporary space of global capitalism. 1 The story of the East India Company is not simply part of the history of the British colonization of India, which began with the Empire’s mercantile arm. Its new ownership is now equally the story about Indian neoliberal patriotic pride at the appropriation of an originary moment from the British Raj’s history: In one of history’s ironic twists, a Gujarati man born in Bombay now owns the company that was set up at Leadenhall Street at the end of the 16th century by British traders and merchants who went around the globe looking for a good cuppa and some spices and ended up colonising half the world—including India, the jewel in the crown—before collapsing in 1873. The company has been revived, but now it sells luxury teas, coffees, chocolates, jams, biscuits and chutneys. - eBook - PDF

A Business of State

Commerce, Politics, and the Birth of the East India Company

- Rupali Mishra, Rupali Mishra Mishra(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

Although this proved unsuccessful, it highlighted how a body like the East India Company might move between the categories of commercial and impe-rial. 44 Additionally, as Philip Stern has shown, “empire” was not exactly out of the question for a trading company, even without crown influence. His work on the late seventeenth-century East India Company is further testa-ment to how tenuous the distinction between “commercial ventures” and “empire” was. The Company-state, in his formulation, was a sovereign body in the late 1600s—it was effectively an imperial power, exercising sover-eignty over the territories and peoples it controlled in the East Indies. 45 The variety and types of English actions abroad, in other words, defy simple categorization. Cases like the East India Company, therefore, prompt a deeper under-standing of English activities abroad in the early modern period, and of the relationship between the Stuart state and overseas activities—some of which focused on settlement and conquest, and some of which did not. In the early seventeenth century, the Company was a determinedly nonim-perial international actor, yet one that grappled on a daily basis with the question of what role the state could and should play in its overseas activi-ties. The example of the East India Company reveals how Company and crown struggled with conceptual questions of the relationship between the state, empire, and overseas activities in the early seventeenth century and underscores the connection between overseas activities and state formation. 14 A Business of State - eBook - PDF

The Scandal of Empire

India and the Creation of Imperial Britain

- Nicholas B. Dirks, Nicholas B Dirks(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Belknap Press(Publisher)

7 British liberalism, buttressed by beliefs in progress and the liberating potential of education and civilization, came to accept empire as a necessity, if only in the short term. And it was hardly surprising that empire became natural in part as a consequence of Britain’s grow-ing prosperity and dominance, constituting strong arguments in fa-139 Economy vor of a firm, if benevolent, imperial hand. The global utopia of the new world of commerce and exchange did not turn out quite as predicted by the thinkers of the Scottish Enlightenment after all. The history of the East India Company’s monopoly is thus the ex-ception that proved the rule of capitalist modernity in Britain, both in its early phases through the end of the eighteenth century and later in its gradual demise and absorption into formal empire during the first half of the nineteenth century. In the first instance, the East India Company had been able to begin to compete with the Dutch and establish a reputation for quick and regular profitability pre-cisely because it had been granted monopoly status and official sanction from the Crown, as well as because it established a system of internal governance that was as efficient as it was careful to main-tain close relations both with the state and its investors. East India trade began with pepper, much of it from various Southeast Asian islands, and later diversified to include other spices such as cloves, nutmeg, mace, and cinnamon. Soon, however, goods from the In-dian mainland became even more important, beginning with indigo (a textile dye) and including saltpeter (used in preserving meats and for making gunpowder) as well as light textiles such as calicoes and silk. A warehouse system was established in various port cities, where Company representatives set up warehouses (factories) that organized local trade and stored at the ready the goods that were to be exported upon the arrival of Company ships. - Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

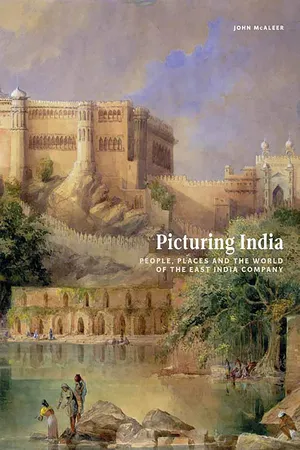

Picturing India

People, Places, and the World of the East India Company

- John McAleer(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- University of Washington Press(Publisher)

INTRODUCTION The East India Company and British Views of India Eighteenth-century India was ‘the theatre of scenes highly important’ to Britain. 1 So wrote the artist and traveller William Hodges. He was in a good position to judge. Hodges was one of the first British professional landscape painters to visit India, spending six years there under the patronage of Warren Hastings, the most important British official in the subcontinent. As well as painting portraits and creating other works for Hastings, Hodges undertook extensive travels throughout India. And all of these experiences were documented in sketches and drawings, many of which were later worked up into finished oil paintings or published as prints (Fig. 1.1). In matters of trade and war, the Indian subcontinent had assumed an increasingly important role in British political and economic life in the second half of the eighteenth century. This relationship between Britain and India was complex and had its roots in the activities of a London-based trading company. The ‘Company of Merchants of London, trading to the East Indies’ – usually abbreviated as the East India Company – controlled British trade with Asia from its foundation in 1600 until the nineteenth century, and was once described as ‘the wealthiest and most powerful commercial corporation of ancient or modern times’. Any examination of Britain’s relationship with India must take account of this extraordinary organisation. 2 By the time Hodges was working, the Company had become a powerful economic and political player there. And its influence was felt not just in Asia. The Company’s commercial, political and military activities altered the way politicians and merchants in Britain thought about the wider world. Ultimately, it helped to lay the foundations of the British Raj - Jim Freedman, Jerome H. Barkow, Jim Freedman, Jerome H. Barkow(Authors)

- 1975(Publication Date)

- University of Ottawa Press(Publisher)

MacLeod, Celt and Indian: Britain's Old World Frontier in Relation to the New, in P. Bohannon and F. Plog, Beyond the Frontier: Social Process and Cultural Change, New York: Natural History Press, 1967, pp. 25-41. Such corporations are said to have begun under James VI of Scotland in 1599, with the express powers to make war as necessary. 4 Conflicts and confusion that had developed in the course of the 17th Century between the Company, the Interlopers or free merchants (who traded in the East despite the monopoly charter held by the East India Company), the London stockholders and the Company servants engaged in private trade were resolved in 1702 by reorganization and unification of the New Company (the Interlopers) and the Old Company. Mukherjee quotes Karl Marx thusly: 'The true commencement of the East India Company cannot be dated from a more remote epoch than the year 1702, when the different societies, claiming the monopoly of the East India Trade, united together in one single company.' (Mukherjee 1974:87). From that time on, also, the systematic expansion of the Company begins, although i t s emergence as a p o l i t i c a l and military system is most clear following the death of the Mughal Emperor and the fragmentation of centralized power in India in the mid-18th Century. The Company then treated as an independent state with local Indian rulers and no longer operated within the port of trade relation, thus effectively reversing the relation of Indian state and English Merchant Company. 5 The port of trade was distinctively developed in the Middle East and India, and mercantile affairs were handled almost wholly by non-Muslim ethnic groups in every country and province, except that in India and further East, Muslims became the merchants in non-Muslim dominated societies.- eBook - ePub

The Route to European Hegemony

India’s Intra-Asian Trade in the Early Modern Period (Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries)

- Ruby Maloni(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

213 The assimilation of Indian entrepreneurs into the new commercial system was a long drawn and complicated process. The response of the Indian mercantile system to the new unfolding parameters of trade was neither static nor unimaginative. Indian merchants attempted to grapple with the fluctuations in power politics and new mercantile entrants. From their earlier position as part of a self-contained system, they finally became part of the European world economy. Working within a difficult and ambivalent relationship, and forced to alter attitudes and practices, the Indian merchant would continue to trade in the maritime domain of Asia and traverse the Indian Ocean.NOTES

1 . K.N. Chaudhuri, The English East India Company: The Study of an Early Joint-Stock Company, 1600-40, Frank Cass & Co., London, 1965, pp. 22, 28, 209.2 . K.N. Chaudhuri, ‘The East India Company and its Decision-making’, in East India Company Studies: Papers Presented to Professor Sir Cyril Philips, ed. K. Ballhatchet and J.Harrison, Asian Research Service, Hong Kong, 1986, pp. 97-121; Ann M. Carlos and Stephen Nicholas, ‘“Giants of an Earlier Capitalism”: The Chartered Trading Companies as Modern Multinationals’, in Business History Review, vol. 62, issue 3, Autumn, 1988, pp. 398-419.3 . K.N. Chaudhuri, ‘The English East India Company in the 17th and 18th Centuries: A Pre-modern Multinational Organization’, in Companies and Trade: Essays on Overseas Trading Companies during the Ancien Regime, ed. L. Blussé and F.S.Gaastra et al., Leiden University Press, Leiden, 1981, p. 38.4 . C. Northcote Parkinson, Trade in the Eastern Seas, 1793-1813, Cambridge, 1937, reprint, Frank Cass & Co., London, 1966, pp. xi, 9, 16,17.5 . Holden Furber, Rival Empires of Trade in the Orient, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1976, p. 227.6 . H.V.Bowen, The Business of Empire: The East India Company and Imperial Britain, 1756-1833, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006.7 . Philip Stern, The Company State: Corporate Sovereignty and the Early Modern Foundations of the British Empire in India, - eBook - PDF

Archives of Empire

Volume I. From The East India Company to the Suez Canal

- Barbara Harlow, Mia Carter, Barbara Harlow, Mia Carter(Authors)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Duke University Press Books(Publisher)

INTRODUCTION Adventure Capitalism: Mercantilism, Militarism, and the British East India Company mia carter F rom its inception at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the British East India Company combined military and commercial methods of institutional organization and administration; what began as a corporate enterprise soon evolved into a massively armed colonial empire. The Company’s history is characterized by intrigue, national and personal ambition, double-dealing, and even kidnapping and hostage-taking as means of insuring successful treaty negotiations. Great Britain’s knowledge of Indian trade was itself acquired by an act of piracy on the high seas when Sir Francis Drake captured five Portuguese vessels containing treasures of the East and detailed documents on trade routes and procedures. The Company also fi-nanced itself for a number of years by illegally importing opium to China; Chinese resistance to England’s drug trade led to the Opium Wars (1839– 1842, 1856–1860) and Britain’s seizure of Hong Kong. The East India Com-pany was also used by English families as a disciplinary institution for incorri-gible sons. ‘‘Naughty’’ Robert Clive, a delinquent and leader of a protection racket at home, was sent to India to improve himself; he earned a knighthood for his military and administrative services on the Company’s behalf. Clive eventually became a British national hero and one of the leading and most-celebrated icons of British imperial masculine identity. Early on in the Company’s history, aggressive protection of its monopoly status was one of the corporation’s chief aims. Free trade was discouraged and eventually outlawed. Private competitors were either eliminated, like Captain Kidd, who was executed for piracy in 1701, or incorporated, like Thomas ‘‘Diamond’’ Pitt, an interloper who had individually obtained trading rights from Indian rulers. - eBook - PDF

Histories of Medicine and Healing in the Indian Ocean World, Volume One

The Medieval and Early Modern Period

- Anna Winterbottom, Facil Tesfaye, Anna Winterbottom, Facil Tesfaye(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

5 Medicine, Money, and the Making of the East India Company State: William Roxburgh in Madras, c. 1790 Minakshi Menon In a fascinating revisionist study of the English East India Company (EIC) in seventeenth-century India, the historian Philip J. Stern has pointed out how the EIC was by its very organization a govern- ment in its own right, deserving analysis on its own terms. He calls it the Company-State, a formation that came into being as part of an early modern empire that was itself constituted through sets of overlapping and competing political forms, of which the EIC was one. 1 Stern reads against the grain of existing historiography on the EIC, which, he says, has led scholars to imagine its politics “as a subset of seventeenth-century English and European politics, political economy, and state formations.” 2 Instead he argues that the EIC’s constitution was volatile, and allowed it a protean exis- tence by balancing various forms of authority, leading it sometimes to claim that it was a “mere merchant” and at others an “indepen- dent sovereign.” Stern reveals continuities between the seventeenth-century EIC and its eighteenth-century incarnation as a territorial power. Both forms governed—administered law, collected taxes, provided pro- tection, inflicted punishment, “enacted stateliness.” Yet he does not tell us how the EIC’s commercial practices affected its gov- ernance in the seventeenth century. What made the hyphenated entity, the Company-State, a distinctive political economic order? 152 Minakshi Menon What aspects of its commercial being organized its stateliness? This chapter takes up these questions in the context of Company state making in Madras in the late eighteenth century. It is usual to speak of the EIC state as a single entity, but the process of its construction varied in its three principal settlements: Bengal, Madras, and Bombay. - No longer available |Learn more

The Evolution of Military Law in India

Including the Mutiny Acts and Articles of War

- U C Jha(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- VIJ Books (India) Pty Ltd(Publisher)

Chapter I The Origin and Growth of East India Company (1600-1858)Towards the end of the fifteenth century rapid discoveries in mathematics, physics, and astronomy facilitated distant navigation. Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama, in an expedition that began in July 1497, became the first person to sail around the Cape of Good Hope to reach India. His revolutionary route proved that it was possible to reach India without hazardous journeys through the Mediterranean and Arabia. The Portuguese fleets brought lucrative Indian spices to Europe from the East-Indies and filled the treasury of the State. It lowered the price of eastern commodities in the Italian markets, and created a spirit for distant navigation and commerce among the rising maritime states in the north of Europe.1 When the Portuguese acquired seats of trade and dominions on the East and West coasts of the Indian peninsula, they found it necessary to establish guards at their factories, to protect the territories which had been ceded to them by the Native Powers.In 1588, the British acquired naval supremacy after defeating the Spanish Armeda.2 This encouraged a few merchants of London to form a company for trade in the East.3 Queen Elizabeth I of England accepted the proposal to send ships to the Indian Ocean, where Spain was not dominant. A Charter was issued by the Queen on 31 December 1600 which granted the merchants’ newly formed organization: “The Governor and Company of Merchants of London, trading to the East-Indies”4 - eBook - PDF

- Peter Robb(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Red Globe Press(Publisher)

The British Company was the most successful of the Europeans, partly through luck, but mainly because it was the best suited to expansion. Its determination was enhanced by the selfish motives of private adventurers, and only at long intervals curbed by inter- ference from a very distant Britain. Cautionary noises from home mostly were heard too late, and the Indian adventures were gener- ally accepted after the event; indeed they benefited from the occa- sional, valuable backing of the British navy, army and state. After 1709, the Company had a local command structure, focused on the three presidencies of Bombay, Madras and Bengal, each with their governor and council. After 1773, by Act of Parliament, the admin- istration in India was placed under the Bengal governor as Governor-General; and, after another Act in 1784, his authority was clarified over his own Council. Under an autocratic but bureau- cratic government, and decisive leadership at key moments, the Company could mobilize resources, and each of the presidencies, though also often competitive, was able to support the others. 128 A HISTORY OF INDIA - eBook - PDF

- Emily Erikson(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Emerald Group Publishing Limited(Publisher)

London: Tru¨ bner. Rothschild, E. (2011). The inner life of empires: An eighteenth-century history . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Seeley, S. J. R. (1891). The expansion of England: Two courses of lectures . London: Macmillan. Sen, S. (1998). Empire of free trade: The East India Company and making of the colonial mar-ketplace . Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. Sen, S. (2002). A distant sovereignty: National imperialism and the origins of British India (1st ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. Spear, P. (1963). The nabobs . Oxford: Oxford University Press. Stein, B. (1989). Thomas Munro: The origins of the colonial state and his vision of empire . New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Steinmetz, G. (2007). The devil’s handwriting . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago. Steinmetz, G. (2008). The colonial state as social field: Ethnographic capital and native policy in the German overseas empire before 1914. American Sociological Review , 73 , 589 612. Stern, P. J. (2011). The company-state: Corporate sovereignty and the early modern foundations of the British Empire in India . Oxford: Oxford University Press. 284 NICHOLAS HOOVER WILSON Sutherland, L. S. (1947). The East India Company and the peace of Paris. The English Historical Review , 62 (243), 179 190. Sutherland, L. S. (1952). The East India Company in eighteenth-century politics . London: Hyperion Press. Travers, R. (2007). Ideology and empire in eighteenth century India: The British in Bengal . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Vaughn, J. M. (2009). The politics of empire: Metropolitan socio-political development and the imperial transformation of the British East India Company, 1675 1775 . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago. Verelst, H. (1772). A view of the rise, progress, and present state of the English government in Bengal: Including a reply to the misrepresentations of Mr. Bolts, and other writers . London: J. Nourse. Watson, I. - eBook - PDF

The Making of the Raj

India under the East India Company

- Ian St. John(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

Yet at this point two things must be grasped. First, the British Raj that ultimately emerged was neither planned nor envisaged at the commencement of the process. Any suggestion that the East India Company would come to occupy the imperial throne vacated by the Great Mughal would have appeared outlandish to Britons and Indi- ans alike. Second, the expansion of British power within India was not something thrust upon passive or resisting Indians by a masterful colonizing race. Important sections of Indian society have as fair claim to be considered the architects of the Raj as the British themselves. Put another way, the Raj did not just happen to Indians; as befitted the dynamic nature of 18th-century India, they played a leading role in making their own history—even if that history unfolded in ways un- anticipated by the chief actors. If Indians never willed British conquest, they unwittingly helped to make it happen. Indians and the Making of the Raj 11 The paradox of this outcome should not obscure the logic behind it. For the British were deeply implicated in the forces that were making the new India. Most obviously, the Company, by its trading activities, fuelled the growth of the market economy. It purchased cloth, silk, indigo, saltpeter, and spices like pepper and cardamom for export, paying for these goods with silver that was much needed by India’s merchants and government exchequers. In the conduct of its inland trade, the Company was heavily dependent upon the services of merchants, bankers, and scribal castes who negotiated with pro- ducers, transported goods, supplied working capital, and exchanged money. By this means powerful reciprocal interests were created: nu- merous Indian groups—farmers, money lenders, artisans, merchants, rural and governing elites—had a stake in the East India Company and the Company had a stake in them. The Company based its opera- tions in a series of fortified factory ports, notably Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.