Literature

Poetry Slam

A poetry slam is a competitive event where poets perform their work and are judged by the audience or a panel of judges. The performances are often dynamic and engaging, with a focus on the spoken word and delivery. Poetry slams provide a platform for poets to showcase their creativity and connect with audiences in a lively and interactive setting.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

9 Key excerpts on "Poetry Slam"

- eBook - ePub

Anarchism and Art

Democracy in the Cracks and on the Margins

- Mark Mattern(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- SUNY Press(Publisher)

4 Poetry SlamStripped to its bare essentials, slam poetry is poetry that is performed in a competitive environment before a live audience. Judges, usually five, are chosen randomly from the audience with no attempt to first ascertain their ability to judge good from bad poetry. They rate the poets on a scale of zero to ten, with high and low scores tossed and the remaining three averaged. Generally, poems must be three minutes or less with points deducted for going over the time limit, though this can vary significantly across local slams. Poets are judged on the poem itself and its performance. A slam master emcees the show, and also does much of the organizing and preparation.The roots of slam are traced back several millennia to ancient oral traditions found in the Homeric epic, African griots, Zuni priests, Japanese Kojiki poets, and Greek bards who related communal stories via song, poetry, and narrative. According to one source, slam as a competition goes back at least to the first century B.C. when the Greek lyric poet Pindar was bested five times by a lesser-known poet, Korinna, and Pindar went on to ridicule her as a sow. Others note that the ancient Olympics included poetry competitions, with winners receiving laurel crowns. Other competitive roots include Japanese haiku contests and African word battles called “signifying.”Twentieth-century roots and influences include Dadaism, emphasizing childlike spontaneity, intellectual nihilism, and moving art outside the museum and concert hall. The 1950s and 1960s beat poets, who sought to transform poetry from a sedate, genteel diversion enjoyed by elites into something more immediate and accessible, are also cited as influences on slam poetry. Beat poets read in coffeehouses, bars, lofts, and cellars. They broke other rules of academic poetry by inviting audience participation, adding music, and injecting elements that sometimes made the readings appear like drunken chaos. Beat poets also began hosting open mic readings. Many of the same dynamics occurred in the Black Arts movement of the mid-1960s and early 1970s. Affiliated with Black Nationalism, this movement primarily sought to address black audiences, celebrate black culture, and increase black cultural autonomy. Black Arts poets anticipated slam in treating the poem as a performance script rather than simply a written text. They drew from various African and African American cultural elements including street vocabulary and cadence, West African vocabulary, percussion and other musical elements, call-and-response, African spirituality, and the speech cadences of black preachers. Their use of live performance, nontraditional performance venues, an attitude of political resistance, democratic ideals, and a conscious stance of marginality from dominant and official verse cultures would eventually be found in slam poetry as well. Performance art and hip-hop culture of the 1970s and 1980s also laid the foundations for slam. The genesis of slam can also be found in a reaction against the mid-twentieth-century literary world’s “New Criticism,” with its focus on structure and content of literary texts in isolation from both audience response and social context. Finally, slam poets would react against the perceived poverty of the traditional poetry scene of the 1970s and 80s; and against the elitism of traditional poetry and literary worlds.1 - eBook - PDF

Listening Up, Writing Down, and Looking Beyond

Interfaces of the Oral, Written, and Visual

- Susan Gingell, Wendy Roy, Susan Gingell, Wendy Roy(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Wilfrid Laurier University Press(Publisher)

In addition, the heterogeneity of slam demonstrates the ease with which the page/stage divide can obscure subtle yet important distinctions within oral poetry forms, thus emphasizing the problematic nature of such broad-brush dichotomies. Before I expand on this argument, however, it is important to say a little more about the nature and history of slam. As I explained in “(Re)present-ing Ourselves,” “Poetry Slam is a movement, a philosophy, a form, a genre, a game, a community, an educational device, a career path and a gimmick” (201). At its core is a knockout oral poetry competition in which poets are judged on the composition and performance of their work. Scoring is typi-cally carried out by randomly selected audience judges, although as the above example indicates, there are many variations on this system, especially out-side the United States. Besides being a competition, slam is associated with a particular style of poetry (and performance), and “slam poetry” is an impor-tant aspect of the phenomenon. In order to capture this dual (and contested) identity as both art form and forum, I refer to slam throughout this essay as a “for(u)m.” Slam’s history spans more than two decades and thousands of miles. The first official Poetry Slam was organized and run in 1986 by Marc Smith at the 82 Listening Up: Performance Poetics Green Mill Tavern, Chicago (Heintz). This Uptown Poetry Slam continues to run on a weekly basis, attracting poets from across the United States and beyond. Since its inception, slam has expanded into numerous geographical and social contexts. One of the most interesting of these is the development of youth slam (Gregory, “Quiet”). While slam follows poetry as a whole in remaining a rather “niche” art, it has grown into perhaps the most popular poetry movement of recent decades (see, for example, Gioia). - eBook - ePub

- Javon Johnson(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Rutgers University Press(Publisher)

Bloom’s claims about slam and his list of poets who know how to use “exactly the right word in exactly the right context” read like white male angst (Barber et al. 2000, 379). Because Poetry Slams represent a forced diversity in terms of bodies, content, and structure, his dismissal is a trite and terrible attempt to save white male normativity, white structures, and the supposed sanctity of the white literary world. Even the mention of an applause meter points to the assumption that only the great literary critics, who are far too often white and male, possess the ability to adequately assess good literature. His comment made many the poets who slam feel as if all of academia were against our work and us. While some creative writing programs and English departments do not recognize the literary merits of slam, many do; and numerous campus program boards and departments are excited to bring slam and spoken word poets to their campuses to perform, lecture, and conduct workshops.Bloom’s generalized dismissal, which is well known in slam and spoken word poetry communities for having reduced slammers to non(sense) poets, failed to account for the many slam participants who have earned degrees in creative writing from respected programs, published in reputable journals, and won highly coveted writing awards. Plenty of us have tried in earnest to prove we are not the death of art by emulating and participating in the very structures that Bloom accepts as legitimate. I appreciate these efforts, but I am also incredibly interested in slam and spoken word poets who imagine and build institutions and coalitions beyond and outside of the academy. My hope is that, rather than trying to prove our merit and usefulness to the literary world, we can consider the possibility that the death of art—at least in the ways in which Bloom imagines art—can be generative.The Poetry Slam or Slam Poetry

The Poetry Slam is the competitive art of performance poetry. It puts a dual emphasis on writing and performance, encouraging poets to focus on what they are saying and how they are saying it. In contrast, spoken word can happen in an open mic format without structured competition or scoring. Traditionally, Poetry Slams consist of multiple poets who are judged by five randomly selected audience members. Immediately following each performance, the judges rate the competitor, using a rubric with a low of 0 and a high of 10, encouraging decimal points in order to decrease the chance of ties. The bout manager drops the highest and lowest scores and averages the middle three scores, and the total may range from 0 to a perfect 30. The rules of individual venues vary—for instance, in the number of rounds required in a bout—but the energy and spirit of the slam remain consistent. - eBook - ePub

- Lucy English, Jack McGowan, Lucy English, Jack McGowan(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

democratizing poetry cemented itself as a key tenet of slam; allowing any artist to perform and any audience member to judge poetry for themselves, no matter what their social or academic background. “When this format caught on and began being replicated in other cities around the world,” Gilpin explains, “Poetry Slam became a movement—one where all voices and poetic styles were welcome … The key premise of the Poetry Slam movement is that elite cultural gatekeepers should not determine whose voice is heard and whose is not” (Gilpin).Thus, beyond purely a format, Poetry Slam took hold as a movement. While its failures and successes have been debated, the movement became known for aiming to open up the art form to artists and audiences who had previously felt poetry was not accessible to them.Slam poetry – what is it?

‘Slam poetry’ is a term that means different things to different people. Numerous essays, including those by Canadian poet Chris Gilpin and Scotland-based poet and researcher Katie Ailes, pick apart the term in great detail. Some use ‘slam poetry’ interchangeably with ‘spoken word’ or ‘performance poetry’, others as shorthand for ‘poetry that isn’t boring’ when marketing events, for example. Both of these usages see poets who have never stepped foot near a slam labelled as ‘slam poets’. Indeed, aside from clumsy mislabelling, in some contexts the term ‘slam poet’ seems to be used more subtly to make inferences about a poet’s work or identity; former Young London Laureate Momtaza Mehri, for example, experienced being labelled a ‘slam poet’ despite never having participated in slam and points to the term’s usage as a marker that can be highly racialized and classed, particularly in more formal or less diverse poetry spaces (Mehri 2020 - No longer available |Learn more

Modern American Poetry

Points of Access

- Kornelia Freitag, Brian Reed(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Universitätsverlag Winter(Publisher)

Each of these poets reveals his or her distinct performance aesthetics, yet they are all connected through a creative outburst when they compete against each other with their poetic texts in front of a live audience. Despite slam's reputation as a relatively young urban literary phenomenon, Poetry Slams should be seen as part of a much longer tradition of performing poetry in the United States. This tradition's early history includes, for example, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, an early African American feminist lecturer and poet-performer and the touring poets Charles Whitcomb Riley and William Carlton from the late 19 th century. In the 20th century, numerous poets from the Harlem Renaissance, the Beat Generation, feminist poets and spoken word poets, as well as rap and hip hop artists, have made performance their most lived form of poetic expression (cf. Pfeiler 2003; Wheeler 2008). 196 197 Across the Atlantic it would not take long for slam poetry to catch fire among many known and unknown writers in Europe, who were, just like their U.S. counterparts, eager to perform (and not just read) their poems and prose texts in front of an audience. In Germany it does not take a lot of effort to find a Poetry Slam in or near one's hometown or to get informed about upcoming performances by one's favorite slammers through MySlam.Net , a web portal that is supported by the European Union's Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency (cf. http://www.my slam.net). Grassroot initiatives still keep pace with official attempts to turn Poetry Slams into a marketable product that continues to re-ceive considerable media coverage on public and private television in both the United States (HBO, PBS, MTV) and Germany (ARTE, WDR). In November 2010, the 14 th German International Poetry Slam was hosted in Duisburg as one of the European Cultural Capital events that went on in the Ruhr-Area that year (cf. http://www. slam2010.de). - eBook - ePub

Poetry Writers' Handbook

A Practical Guide to Getting Your Poetry Noticed, Published and Performed

- Sophia Blackwell(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Yearbooks(Publisher)

The idea of performing poetry for its own sake, without the goal of winning a competition or publishing deal, harks back to the UK spoken word culture of the 1960s to the 1990s, which was focused on happenings, gatherings and protests, messy avant-garde cabaret nights and pub or punk poets who crossed over or graduated into another genre such as music or stand-up comedy. The 1980s saw a resurgence of stand-up comedy in the UK, and some poets began their careers at The Comedy Store in London as part of mixed poetry and comedy acts and received recognition through appearing on John Peel’s radio shows. The crossover potential between spoken word, comedy and theatre may have weakened a little in the late 1990s and early 2000s with the vogue for American-influenced, socially conscious poetry which relied on a pure, visceral style of delivery. Slam poetry bans music and props from the stage and favours poets who memorise their work and deliver it in the style of a preacher channelling the Word from a higher place. For the UK poetry scene, Slam was a nicely timed shake-up and a challenge to the established order at a time when the most recent three Poets Laureate were Sir John Betjeman, Ted Hughes and Andrew Motion. However, Slam’s constraints and the focus on a pure, unmediated style of delivery (which is also artifice) may have limited its practitioners’ imaginations. Slam rules do not allow for a meaningful combination of written work with other art forms such as song or visuals and may have discouraged poets from creating works that were too long for them to memorise or to fit within the three-minute time limit.Poetry SlamsA Poetry Slam is a live poetry competition, where poets perform their work for points from the audience and/or judges. The first Slam was held in Chicago in 1986, when Marc Smith decided to provide an alternative to stuffy off-the-page poetry readings. It proved popular, encouraging voices from all walks of life and many different styles of poetry. The first UK Slam took place in 1994. Many Slams have a ‘sacrificial’ poet to calibrate the audience; that person goes first and is subject to the same rules as the other performers, but their scores are not counted as part of the final competition. Poets can compete as teams or individuals. In a Poetry Slam, selected members of the audience can judge the poets on stage. The rest of the audience (who may be judges or non-judges trying to sway the people or groups judging) clap and whoop at a level designed to coax the judges into giving a higher score or clap quietly to indicate they’d be happier with a lower one. Some Slams and tie-breaks are also judged by an informal audience clapometer, rather than judges or groups, with the MC choosing the victor based on the volume of applause. US and UK Slams start to deduct points once the performer has been speaking for longer than three minutes, or three minutes and a pre-defined grace period, while European Slams tend to be more flexible on timings. Musical accompaniment and props are grounds for disqualification, but there are some grey areas such as: - eBook - PDF

Making Poetry Happen

Transforming the Poetry Classroom

- Sue Dymoke, Myra Barrs, Andrew Lambirth, Anthony Wilson, Sue Dymoke, Myra Barrs, Andrew Lambirth, Anthony Wilson(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

(Links to these are mentioned later in the chapter.) The live event experience Nothing can compete with the live event experience, certainly for a spoken word artist. The stage is as much a part of the script for the slam poet as the words themselves. We must constantly be aware of the semantics of performance, of writing a piece that will be instantly effective and understood and of knowing not only our words but also what script the body will be speaking. At traditional poetry readings, it is not uncommon for the featured poet to ask the audience to refrain from applause until the end of their sets; in slam the applause and screams of the audience becomes a part of the poem. Authors need to wait up to a year or two to discover what their readership thinks and feels about their new works. The slam poet gets to know immediately whether they have been successful or not. In spite of this, I have yet to hear of slam experience which has not been positive for the artist. A core difference between SLAMbassadors and other youth slams is perhaps that we treat each slam as we would an adult event. That means we do not have team poems, synchronized movements or penalties for going over a time limit. In slam events, marks are awarded on Writing Technique, Performance and Originality, often with points deducted for time breaches. Winners are selected after a lengthy discussion on whether it is believed that they fit the profile of a spoken word artist. We look for one poet. One voice. One potential career in spoken word. Continued mentoring The point of the slam event is to inspire continued creation of original poetry and spoken word. It is not the full stop, but a comma. What happens SLAM POETRY 131 next is always more important than what has just happened on one stage in one town in one part of the world. Continued intensive mentorship is at the core of the SLAMbassador programme, for all participants and not just the winners. - Timothy Yu(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

In what follows, we trace the movement of slam and spoken-word poetry from a subjugated and lesser art form to an established and valid one, while suggesting that these institutionalizing forces and desires can be caught up in anti-Blackness. 2 Despite never having seen a slam in person, the noted literary critic Harold Bloom has notoriously called Poetry Slams “the death of art” (Johnson 1). Bloom’s troubling statement, which is unable to recognize anyone other than the great white male literati as valid and valuable, as well as the fact that a number of early slam and spoken-word poets were denied access to academia via publishing, grants, and graduate programs demonstrate that traditional institutions initially relegated the slam to the status of an unsophisticated low art. As depicted in the critically successful documentary SlamNation (1998), then executive editor of St. Martin’s Press, Jim Fitzgerald, dismisses Jessica Care Moore’s manuscript by offering slam as “neat” yet “on the decline.” He diminishes Moore’s rising popularity, explaining, “Jessica’s appearance on the cover of the New York Times was probably an attempt by the New York Times to say ‘we’re hip and we’re doing the youth thing.’” In other words, publishing houses and the university, as Gioia mentions, acted as poetic gate- keepers and, we argue, pushed the new art and artists to the margins or jettisoned it and them all together. The rejection forced some slam and spoken- word poets to build workshops, classes, curricula, and publishing houses. Others have sought to legitimize themselves and the art form by publishing in reputable spaces, earning degrees, and winning grants and awards. Still others have tried some sort of mix of the previous two. These cultural tensions around the legitimacy and institutionalization of slam and spoken word are deeply tied to these poetry communities’ relationship with race, and particularly Blackness.- eBook - ePub

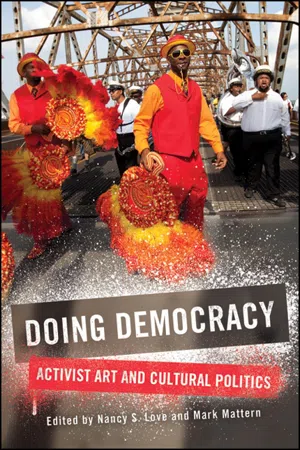

Doing Democracy

Activist Art and Cultural Politics

- Nancy S. Love, Mark Mattern, Nancy S. Love, Mark Mattern(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- SUNY Press(Publisher)

Slam models a relationship in which the community and individual freedom are both inextricably tied and mutually supportive, and where sociability is viewed not as an impediment to human autonomy but as a requirement for it. Slam poetry is a world of free expression, inspiration, and creation. Slam poets experience their freedom because of social connections and the community ties in which they are embedded. Their freedom, in short, is made possible by community, not threatened by it. This is a more democratic conception because, to do democracy, citizens must find or create common ground where shared issues and problems can be recognized, acknowledged, and addressed. Precisely part of the problem today in the contemporary United States is the failure to find or create this common ground, which can be attributed in part to the radical individualism and related liberal freedom that dominates.Closing: Slam as Prefiguration

The arts, based as they are on a foundation of imagination and creativity, offer fertile terrain for developing and identifying new possibilities for thought and action. Artists attempt to reach beyond convention to create and express new meaning. They help us “articulate the unspoken,” and this “brings about interesting futures.”46I have argued that slam's structure—the way it is organized and practiced—reflects and sustains an ethos of democracy where norms of equality and freedom pervade, and in which active, widespread participation is expected and encouraged, barriers to participation removed, critical consciousness systematically encouraged, and power leveled. It gives participants a direct experience of “doing democracy” that is deeper and more tangible than the thin version most take for granted in a liberal democracy. In all of these ways, slam suggests future, more democratic, possibilities. It opens new horizons of thought and action.Of course, slam is not immune from undemocratic influences and pressures. The generally progressive and liberal leanings of slam poets and audiences do not ensure the absence of occasional racist, sexist, heterosexist, homophobic, and other undemocratic messages in the content of slam poetry. Similarly, can slam as a democratic art form survive against the pressures of a profoundly undemocratic political economy and mass culture? Despite the overt opposition to commercialization of slam, in recent years some slammers have expressed concern that slam is nevertheless slipping increasingly toward commercialism in the same way as occurred with rap, that “there is a developing shift within slam from art to commerce.”47 According to Marc Smith, despite having “resisted the commercial exploitation of the slam … the door to commercialization is now wide open.”48

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.