Psychology

PTSD

PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder, is a mental health condition that can develop after experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event. Symptoms may include flashbacks, nightmares, severe anxiety, and uncontrollable thoughts about the event. PTSD can significantly impact a person's daily life and functioning, but with proper treatment, such as therapy and medication, individuals can learn to manage their symptoms and improve their quality of life.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "PTSD"

- No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Orange Apple(Publisher)

____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ____________________ Chapter- 3 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Posttraumatic stress disorder (also known as post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD ) is a severe anxiety disorder that can develop after exposure to any event that results in psychological trauma. This event may involve the threat of death to oneself or to someone else, or to one's own or someone else's physical, sexual, or psychological integrity, overwhelming the individual's ability to cope. As an effect of psychological trauma, PTSD is less frequent and more enduring than the more commonly seen acute stress response. Diagnostic symptoms for PTSD include re-experiencing the original trauma(s) through flashbacks or nightmares, avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma, and increased arousal – such as difficulty falling or staying asleep, anger, and hypervigilance. Formal diagnostic criteria (both DSM-IV-TR and ICD-9) require that the symptoms last more than one month and cause significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Classification Posttraumatic stress disorder is classified as an anxiety disorder, characterized by aversive anxiety-related experiences, behaviors, and physiological responses that develop after exposure to a psychologically traumatic event (sometimes months after). Its features persist for longer than 30 days, which distinguishes it from the briefer acute stress disorder. These persisting posttrau-matic stress symptoms cause significant disruptions of one or more important areas of life function. It has three sub-forms: acute, chronic, and delayed-onset. Causes Psychological trauma PTSD is believed to be caused by either physical trauma or psychological trauma, or more frequently a combination of both. - Robert J. Sbordone, Ronald E. Saul, Arnold D. Purisch(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

6 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) refers to the development of a set of specific symptoms following exposure to traumatic and physical events such as combat, fire, flood, molestation, nat-ural disasters, rape, or witnessing someone badly injured or killed, and so forth. According to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (Amer-ican Psychiatric Association, 1994), an individual who develops PTSD must be confronted with an event or events that involve actual or threatened death, or serious injury, or threat to the phys-ical integrity of self or others, which produces intense feelings of fear, helplessness, or terror. The diagnostic criteria for PTSD requires that the traumatic event be persistently reexperienced by either recurrent or intrusive recollections, distressing dreams, flashbacks, or by stimuli that symbolize or resemble some aspect of the traumatic event; conscious efforts to avoid specific thoughts, feelings, people, places, or activities that could trigger recollections of the event; symp-toms of emotional arousal (e.g., hypervigilance) and heightened reactivity (e.g., exaggerated startle responses). ACUTE STRESS DISORDER The diagnosis of Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) was introduced in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) by the American Psychiatric Association in 1994 and was conceptualized as an acute form of PTSD, which occurs within 1 month following exposure to a traumatic event. While ASD has been regarded as a predictor of a PTSD (Bryant and Harvey, 1997), Harvey and Bryant (1998) found that 40% of the individuals who met the diagnostic criteria for ASD did not develop chronic PTSD.- eBook - PDF

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Diagnosis, Management and Treatment

- Graeme Turner, David Nutt, Murray Stein, Joseph Zohar, David Nutt, Murray Stein, Joseph Zohar(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

1 Posttraumatic stress disorder: Diagnosis, history, and longitudinal course Arieh Y Shalev WHAT IS POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER? Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an anxiety disorder defined by the co-occurrence in sur-vivors of extreme adversity reexperiencing avoidance and hyperarousal symptoms.(1) Unlike most other mental disorders, the diagnosis of PTSD relies on associating concurrent symptoms with a previous “traumatic” event. The association is both chronological (symptoms starting after the event) and content related: PTSD reexperiencing and avoidance symptoms involve recollections and reminders of the traumatic event. Individuals who suffer from PTSD continu-ously and uncontrollably relive the very distressing elements of the traumatic event in the form of intrusive recollection and a sense of permanent threat. They avoid places, situations, and mental states that can evoke such recollections. The image of men and women condemned to repeatedly relive a traumatic event has always captured human imagination. It was immortalized in ancient legends, such as that of Lot’s wife, petrified into a column of salt, as she looked backward to the chaos of Sodom. This metaphor of being frozen by looking back at the trauma served as inspiration for generations of artists (see adjacent figures) More recent expressions depict combat soldiers as ones for whom “the war does not end when the shooting stops” (2) or the holocaust survivors who experience the components of the horror decades after liberation.(3) Beyond reminders of the traumatic event, PTSD symptoms include pervasive alterations in one’s emotional life, in the form of depressed mood, tension, restlessness, and irritability (Box 1.1). PTSD, therefore, encompasses trauma-related symptoms, anxiety symptoms and symptoms otherwise found in depression. - eBook - ePub

Clinical Psychology

A Global Perspective

- Stefan G. Hofmann(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

12 Posttraumatic Stress DisorderRichard A. BryantAs countries around the world confront a wide array of traumatic events, there is increasing concern about the adverse mental health effects of trauma. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the most studied posttraumatic psychiatric condition, and the field has advanced enormously in recent decades. In this chapter, the current definitions of PTSD are reviewed in light of recent diagnostic changes; prevailing models are discussed, empirical knowledge of PTSD is critiqued, and treatment strategies are outlined. Although commentators have discussed posttraumatic stress reactions for many hundreds of years, and more substantively since the First World War in the form of “combat shock” (Shephard, 2001), the formal recognition of PTSD only occurred in 1980 to describe posttraumatic reactions of veterans returning from Vietnam.Definition

As with most psychiatric disorders, PTSD has been most commonly defined by the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM) or the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases ICD. In terms of DSM, the fifth edition of DSM (DSM‐5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) was released in 2013 and made some significant changes to how PTSD was operationalized. Keeping to tradition, it included a “gatekeeper” criterion that requires that anyone who is to be considered for a PTSD diagnosis must have been exposed to threatened or actual harm to oneself or others (Cluster A). There are four other major clusters of symptoms that one must satisfy. First, one needs to have at least one of the following: re‐experiencing symptoms, including intrusive memories, flashbacks, nightmares, and distress to reminders of the trauma (Cluster B). Second, one is required to have at least one of: active avoidance of internal reminders of the trauma (e.g., thoughts, memories) or external reminders (e.g., situations, conversations) (Cluster C). Third, and somewhat controversially, DSM‐5 introduced a new cluster of symptoms termed alterations in mood and cognition. This cluster requires at least three of the following symptoms: exaggerated negative thoughts about oneself or the world, excessive blame, pervasive negative emotions, diminished interest, feeling detached or estranged from others, psychogenic amnesia. This cluster raised serious questions by some commentators because it broadened the traditional definition of PTSD from a fear‐based disorder to one that accommodated a wider array of emotional responses (Hoge et al., 2016). The justification for this inclusion was that a definition focused on fear did not adequately encompass the psychological responses of certain populations, and particularly military, emergency responders, and victims of crime (Friedman, Resick, Bryant, & Brewin, 2011). The final cluster involves arousal symptoms, and requires at least three of the following: exaggerated startle response, reckless behavior, insomnia, aggressive behavior, and sleeping and concentration difficulties (Cluster D). DSM‐IV required that the symptoms be present for more than 1 month after the trauma because DSM did not want to pathologize people who may be experiencing a transient stress response. A questionable feature of the new definition of PTSD in DSM‐5 was that it increased the potential heterogeneity of PTSD markedly. Most psychiatric disorders are reasonably limited in the number of ways they can be manifested; for example, in DSM‐5 there were 227 permutations of major depression, 23,442 of panic disorder, one of specific phobia, and one of social anxiety disorder (social phobia). Whereas there were 84,645 possible presentations of PTSD in DSM‐IV - Chapman, Alexander L., Gratz, Kim L., Tull, Matthew T.(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- New Harbinger Publications(Publisher)

Ann Burgess and Linda Holmstrom documented similar psychological symptoms among rape survivors, calling it rape trauma syndrome (Burgess and Holmstrom 1974). Recognizing the personal and public health consequences of these symptoms, advocates for these two groups Understanding PTSD and Its Effect on Your Life 3 began working with researchers and clinicians to develop and bring awareness to the PTSD diagnosis as we know it today (Keane and Barlow 2002). The term PTSD became official with the publication of the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders in 1980. Some changes have been made to the diagnosis since then, but the symptoms associated with PTSD have generally stayed the same. The Symptoms of PTSD To develop the symptoms of PTSD, you need to first experience a traumatic event. So, what is the difference between this kind of traumatic event and the highly stressful events that are common in everyday life? A traumatic event occurs when you are exposed to actual or threat- ened death, serious injury, or sexual violence. This can take the form of directly experiencing the event, witnessing the event, learning about the event (for example, hearing that a close friend or family member was raped), or being repeatedly exposed to unpleasant details of trau- matic events, such as a police officer frequently hearing stories of child abuse (American Psychiatric Association 2013). As you can imagine, there are a number of events that can be considered traumatic. Because we often hear about PTSD in the context of war, there is the common misperception that PTSD is something experienced only by people in the military. This is definitely not the case. Along with combat, the events that can lead to PTSD include natural disasters, a serious accident, physical or sexual assault, and the sudden violent or acci- dental death of another person. With this definition in mind, identify what traumatic events you have experienced in exercise 1.1.- Michel Hersen, Jay C. Thomas(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications, Inc(Publisher)

16 P OSTTRAUMATIC S TRESS D ISORDER J OHAN R OSQVIST , T HRÖSTUR B JÖRGVINSSON , D ARCY C. N ORLING , AND B ERGLIND G UDMUNDSDOTTIR D ESCRIPTION OF THE D ISORDER Although posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) was not formally recognized as a disorder per se until 1980, it is today considered one of the most seri-ous and disabling anxiety disorders (Rosqvist, 2005). PTSD, or trauma and various stress reac-tions, is certainly not a new concept; in fact, the notion that people may experience psychological difficulties after exposure to traumatic situations has an extremely long history (Breslau, Peterson, Kessler, & Schultz, 1999; Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith, 1990; Norris, 1992; Resnick, Kilpatrick, Dansky, Saunders, & Best, 1993). Early literature is littered with references to problematic psychological sequelae that may fol-low threatening or harmful events. Andrews et al. (2003) point out that even in Homer’s Iliad, nearly three thousand years ago, suggestions were made about “psychological problems fol-lowing a traumatic experience” (p. 465). Later writers and philosophers (e.g., Shakespeare) are also known to have alluded to a particular set of symptoms that today we call PTSD or acute stress disorder (ASD; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Although both PTSD and ASD are driven by trauma, the central difference between the two trauma-related anxiety disor-ders is that ASD occurs soon after trauma, whereas PTSD occurs after a delay of at least a month (Rassin, 2005). Nonetheless, recent history, such as the American Civil War and World War I, also produced such early but not formally organized descriptions of these phe-nomena as shell shock and battle or combat fatigue. Fortunately, for many people with symp-toms of PTSD, such problems subside with time, but some need formal intervention to achieve true relief.- eBook - PDF

- John I. Nurnberger, Jr, Wade Berrettini(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Additionally, such symptoms must persist for at least one month and significantly impair daily functioning [2]. History of the construct The definition of PTSD as a mental disorder, how- ever, has evolved over time. While ideas about the negative psychological impact of trauma have been accepted for centuries [3], PTSD did not have a formal psychiatric definition until 1980 in DSM-III [4]. Inclusion of PTSD in DSM-III marked formal acknowledgement from the psychiatric community that the effects of trauma should be considered from a mental health perspective, that inherent personal weakness does not drive traumatic sequelae, and that the negative experiences of those having suffered trauma are legitimate [5]. However, before this shift, recognition of the psychological importance of trauma was not universal. In fact, psychological sequelae of traumatic events only became an important focus of medicine during the American Civil War. Pizarro et al. [6] reported that 44% of soldiers reported signs of mental or “nervous” disease after the Civil War, which was often called “irritable heart” by nineteenth-century physicians. Also, individuals suffering from mental and physical reactions to train accidents spurred the notion of “railway spine” or “postconcussion syndrome” ([79], as cited in [5]). Considering that the symptoms of these ailments included sleep disruptions, nightmares about train accidents, avoidance of train travel, and chronic pain, Oppenheim renamed the phenomenon “traumatic neurosis” ([78] as cited in [5]). Reference to psychological reaction to trauma appeared in DSM-I under the label of traumatic neur- osis [7]. However, this disorder was not present in DSM-II [8]. The understanding of psychological reac- tion to traumatic events underwent a metamorphosis throughout this time period, leading up to the inclu- sion of PTSD as a mental disorder in DSM-III [4]. Principles of Psychiatric Genetics, eds John I. Nurnberger, Jr. - eBook - PDF

Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders

A Step-by-Step Treatment Manual

- David H. Barlow(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- The Guilford Press(Publisher)

64 Severe, unexpected trauma may occur in less than a minute but have lifelong consequences. The tragedy that is posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is brought into stark relief when the origins of the trauma occur in the context of people’s inhumanity to others. In this chapter, the case of “Tom” illustrates the psychopathology associated with PTSD in all its nuances and provides a very personal account of its impact. In one of any number of events summarized dryly every day in the middle pages of the newspaper, Tom, in the fog of war in Iraq, shoots and kills a pregnant woman and her young child in the presence of her husband and father. The impact of this event devastates him. The sensi- tive and skilled therapeutic intervention described in this chapter is a model for new therapists and belies the notion that, in these severe cases, manualized therapy can be rote and automated. In addi- tion, “cognitive processing therapy,” the evidence-based treatment for PTSD utilized with this case, is sufficiently detailed to allow knowledgeable practitioners to incorporate this treatment program into their practice. This comprehensive treatment program takes advantage of the latest developments in our knowledge of the psychopathology of trauma impact by incorporating treatment strategies specifically tailored to overcome trauma-related psychopathology and does so in the context of the significant changes to diagnostic criteria in DSM-5. —D. H. B. PREVALENCE Epidemiological studies document significant rates of trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) across the world (e.g., Atwoli, Stein, Koenen, & McLaughlin, 2015; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995; Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005; Kes- sler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005; Kil- patrick, Saunders, Veronen, Best, & Von, 1987; Kulka et al., 1990). - eBook - PDF

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Issues and Controversies

- Gerald Rosen(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

with worsening of symptoms, poor attendance, and less treatment involvement (Tarrier & Humphreys, 2000; Tarrier, Pilgrim, & Sommerfield, 1999). Overall, research demonstrates that PTSD is best understood as the periodic expression of long-standing dispositions that often are risk factors for both threatening exposures and subsequent dysfunctions. At the very least, pre-event risk factors that include enduring personality features and beliefs have been found to predict PTSD more reliably than event features. Considering these issues in case formulations will help clinicians integrate salient risk and resilience factors into a unique whole, in order to best care for each individual. REFERENCES Afana, A.-H., Steffen, O., Bjertness, E., Grunefeld, B., & Hauff, E. (2002). The prevalence and asso- ciated socio-demographic variables of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) among patients attending primary care centers in the Gaza Strip. Journal of Refugee Studies, 15, 283–295. Aldwin, C. M., Sutton, K. J., & Lachman, M. (1996). The development of coping resources in adult- hood. Journal of Personality, 64, 837–871. Ali, T., Dunmore, E., Clark, D., & Ehlers, A. (2002). The role of negative beliefs in posttraumatic stress disorder: A comparison of assault victims and nonvictims. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 30, 249–257. Alvarez-Conrad, J., Zoellner, L. A., & Foa, E. B. (2001). Linguistic predictors of trauma pathology and physical health. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 15, S159–S170. American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th edn). Washington, DC: Author. Antonovsky, A. (1979). Health, stress, and coping. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Argyle, M. (1987). The psychology of happiness. London: Methuen. Asmundson, G. J. G., Bonin, M. F., & Frombach, I. K. (2000). Evidence of a disposition toward fearfulness and vulnerability to posttraumatic stress in dysfunctional pain patients. - eBook - PDF

Handbook of PTSD

Science and Practice

- Matthew J. Friedman, Paula P. Schnurr, Terence M. Keane, Matthew J. Friedman, Paula P. Schnurr, Terence M. Keane(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- The Guilford Press(Publisher)

DSM-5 Criteria for PTSD 25 diagnosis. After considering this alternative (see Friedman et al., 2011b), the DSM-5 Work Group concluded that it was necessary to preserve criterion A1 as an indispens- able feature of PTSD because PTSD does not develop unless an individual is exposed to an event or series of events that are intensely stressful. McNally (2009) argued that the memory of the trauma is the “heart of the diagnosis” and the organizing core around which the B–E symptoms can be understood as a coherent syndrome. He noted that “one cannot have intrusive memories in the abstract. An intrusive memory must be a memory of something and that something is ‘the traumatic event’ ” (p. 599). The intru- sion and avoidance symptoms are incomprehensible without prior exposure to a trau- matic event. The traumatic experience is usually a watershed event that marks a major discontinuity in the life trajectories of individuals affected with PTSD. A related question was whether A1 should be limited to direct exposure, so that the “learning about” component of the A1 criterion could be eliminated. Several stud- ies have found PTSD among family members whose spouse or child was murdered, assaulted sexually, killed in combat, killed in the September 11, 2001, attack on the World Trade Center, or died violently (see Friedman et al., 2011a). Indirect exposure also applies to professionals who, though never in danger themselves, are exposed to the grotesque details of war, rape, genocide, or other abusive violence to others (see Friedman et al., 2011a). An extensive review (Ursano, Fullerton, & Norwood, 2003) documented the prevalence of elevated PTSD among civilian and military personnel and families indirectly exposed to traumatic death following combat, terrorism, and disasters. - eBook - PDF

- Victor Olisah(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- IntechOpen(Publisher)

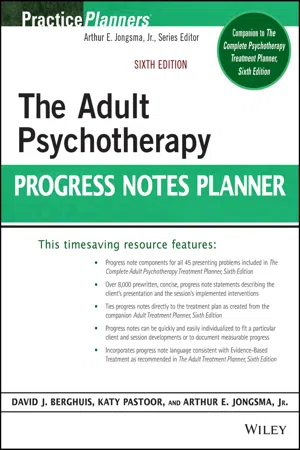

Bodkin, A., Pope, H. G., Detke, M. J., & Hudson, J. I. (2007). Is PTSD caused by traumatic stress? Journal of Anxiety Disorders , Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. (176–182), 0887-6185. Bonnano, G.A. (2005). Resilience in the face of potential trauma. Current Directions in Psychological Science , Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. (135-138), 0963-7214. Boyraz, G., & Efstathiou, N. (2011). Self-focused attention, meaning, and posttraumatic growth: The mediating role of positive and negative affect for bereaved women. Journal of Loss and Trauma , Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. (13-32). Braga, L.L., Fiks, J.P., Mari, J.J., Mello, M.F. (2008). The importance of the concepts of disaster, catastrophe, violence, trauma and barbarism in defining posttraumatic stress disorder in clinical practice. BMC Psychiatry, Vol. 8, No. 68, pp. (1-8). Breslau, N., & Davis, G. C. (1987). Posttraumatic stress disorder: The Stressor Criterion. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, Vol. 175, No. 5, pp. (255–264). Breslau, N., & Kessler, R. C. (2001). The Stressor Criterion in DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder: An empirical investigation. Biological Psychiatry , Vol. 50, No. 9, pp. (699– 704), 0006-3223. Brewin, C.R., (1997). Psychological defenses and the distortion of meaning. In: The Transformation of Meaning in Psychological Therapies, M. Power & C.R. Brewin, pp. (107-123), Wiley, New York. Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B., & Valentine, J. D. (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , Vol. 68, No. 5, pp. (748 − 766), 0022-006X. Brewin, C.R., Lanius, R.A., Novac, A., Schnyder, U., & Galea, S. (2009). Reformulating PTSD for DSM-V: Life after criterion A. Journal of Traumatic Stress , Vol. 22, No. 5, pp. (366-373). Brewin, C.R., Gregory, J.D., Lipton, M., & Burgess, N. (2010). Intrusive images in psychological disorders: characteristics, neural mechanisms, and treatment implications. - Arthur E. Jongsma, Jr., Katherine Pastoor, David J. Berghuis(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER (PTSD) CLIENT PRESENTATION 1. Exposure to Threatened Death/Injury to Self (1) 1 A. The client has been a victim of a threat of death or serious injury to self that has resulted in an intense emotional response of fear, helplessness, or horror. B. The client’s intense emotional response to the traumatic event has somewhat dimin-ished. C. The client can now recall the traumatic event of being threatened with death or serious injury without an intense emotional response. 2. Intense Reaction to Trauma (2) A. The client has a history of having been exposed to the death or serious injury of others that resulted in feelings of intense fear, helplessness, or horror. B. The client’s severe emotional response of fear has somewhat diminished. C. The client can now recall being a witness to the traumatic incident without experienc-ing the intense emotional response of fear, helplessness, or horror. 3. Intrusive Thoughts (3) A. The client described experiencing intrusive, distressing thoughts or images that recall the traumatic event and its associated intense emotional response. B. The client reported experiencing less difficulty with intrusive, distressing thoughts of the traumatic event. C. The client reported no longer experiencing intrusive, distressing thoughts of the trau-matic event. 4. Disturbing Dreams (4) A. The client described disturbing dreams that he/she/they experience and are associated with the traumatic event. B. The frequency and intensity of the disturbing dreams associated with the traumatic event have decreased. C. The client reported no longer experiencing disturbing dreams associated with the trau-matic event. 5. Flashbacks (5) A. The client reported experiencing illusions about or flashbacks to the traumatic event. B. The frequency and intensity of the client’s flashback experiences have diminished. C. The client reported no longer experiencing flashbacks to the traumatic event.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.