Technology & Engineering

Vector Cross Product

The vector cross product is a mathematical operation that takes two vectors and produces a third vector that is perpendicular to both of the original vectors. It is used in various fields of engineering, such as mechanics and electromagnetism, to calculate forces, torques, and magnetic fields.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

8 Key excerpts on "Vector Cross Product"

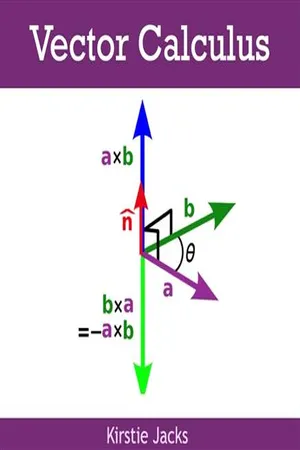

- No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- White Word Publications(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter 5 Cross Product In mathematics, the cross product , vector product , or Gibbs vector product is a binary operation on two vectors in three-dimensional space. It results in a vector which is perpendicular to both of the vectors being multiplied and normal to the plane containing them. It has many applications in mathematics, engineering and physics. If either of the vectors being multiplied is zero or the vectors are parallel then their cross product is zero. More generally, the magnitude of the product equals the area of a parallelogram with the vectors for sides; in particular for perpendicular vectors this is a rectangle and the magnitude of the product is the product of their lengths. The cross product is anticommutative, distributive over addition and satisfies the Jacobi identity. The space and product form an algebra over a field, which is neither commutative nor associative, but is a Lie algebra with the cross product being the Lie bracket. Like the dot product, it depends on the metric of Euclidean space, but unlike the dot product, it also depends on the choice of orientation or handedness. The product can be generalized in various ways; it can be made independent of orientation by changing the result to pseudovector, or in arbitrary dimensions the exterior product of vectors can be used with a bivector or two-form result. Also, using the orientation and metric structure just as for the traditional 3d cross product, one can in n dimensions take the product of n - 1 vectors to produce a vector perpendicular to all of them. But if the product is limited to non-trivial binary products with vector results it exists only in three and seven dimensions. ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ The cross-product in respect to a right-handed coordinate system - eBook - PDF

- James Stewart, Daniel K. Clegg, Saleem Watson, , James Stewart, James Stewart, Daniel K. Clegg, Saleem Watson(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. SECTION 12.4 The Cross Product 855 The Cross Product Given two nonzero vectors, it is very useful to be able to find a nonzero vector that is perpendicular to both of them, as we will see in the next section and in Chapters 13 and 14. We now define an operation, called the cross product, that produces such a vector. ■ The Cross Product of Two Vectors Given two nonzero vectors a - k a 1 , a 2 , a 3 l and b - k b 1 , b 2 , b 3 l, suppose that a nonzero vector c - k c 1 , c 2 , c 3 l is perpendicular to both a and b. Then a c - 0 and b c - 0 and so 1 a 1 c 1 1 a 2 c 2 1 a 3 c 3 - 0 2 b 1 c 1 1 b 2 c 2 1 b 3 c 3 - 0 To eliminate c 3 we multiply (1) by b 3 and (2) by a 3 and subtract: 3 sa 1 b 3 2 a 3 b 1 d c 1 1 sa 2 b 3 2 a 3 b 2 d c 2 - 0 Equation 3 has the form pc 1 1 qc 2 - 0, for which an obvious solution is c 1 - q and c 2 - 2p. So a solution of (3) is c 1 - a 2 b 3 2 a 3 b 2 c 2 - a 3 b 1 2 a 1 b 3 Substituting these values into (1) and (2), we then get c 3 - a 1 b 2 2 a 2 b 1 This means that a vector perpendicular to both a and b is k c 1 , c 2 , c 3 l - k a 2 b 3 2 a 3 b 2 , a 3 b 1 2 a 1 b 3 , a 1 b 2 2 a 2 b 1 l The resulting vector is called the cross product of a and b and is denoted by a 3 b. 4 Definition of the ross Product If a - k a 1 , a 2 , a 3 l and b - k b 1 , b 2 , b 3 l, then the cross product of a and b is the vector a 3 b - k a 2 b 3 2 a 3 b 2 , a 3 b 1 2 a 1 b 3 , a 1 b 2 2 a 2 b 1 l Hamilton The cross product was invented by the Irish mathematician Sir William Rowan Hamilton (1805–1865), who had created a precursor of vectors, called quaternions. - eBook - ePub

Electromagnetics and Transmission Lines

Essentials for Electrical Engineering

- Robert Alan Strangeway, Steven Sean Holland, James Elwood Richie(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Refer to Figure 1.9. Given specific numbers, how could you check this result? () Figure 1.9 Tangential and normal components of vector relative to a boundary, where aligns with the boundary of concern. 1.2.2 Cross Product Another “relationship” between vectors is the extent to which two vectors are perpendicular. The definition of the Vector Cross Product is (1.22) where is the unit vector normal (perpendicular) to the plane containing the two vectors (see Figure 1.10), as determined by the Right‐Hand‐Rule (RHR): Use the curled fingers of your right hand to rotate the first vector () into the second vector () through the smallest angle, as illustrated in Figure 1.10. Extend the thumb of your right hand and it points in the direction. Figure 1.10 Unit vector normal to the plane containing vectors and. Note that the cross product of two vectors is a vector result. The reason is the value of the sin(θ) when θ = 0 °, ± 90 °, and ± 180 °, respectively. Hence, the magnitude of the cross product result is somewhere within the range of: (1.23) As the magnitude of the cross product approaches AB, the two vectors are more orthogonal (perpendicular). Conversely, as the magnitude of the cross product approaches zero, the two vectors are more parallel or antiparallel. Similar to what we initially encountered with the dot product, the cross product definition of Eq. (1.22) requires advance knowledge of the angle between the two vectors. How is the cross product determined when the angle between the vectors is unknown? Start with vectors expressed in Cartesian form and apply the distributive property of the cross product: (1.24) (1.25) What is the cross product between parallel unit vectors? Examine the first term: (1.26) where. These two unit vectors are identical and therefore parallel; hence, the angle is 0° and sin(0°) is zero. Thus, the first term is: (1.27) Similarly, all other terms where the unit vectors are parallel are also zero - eBook - PDF

- Daniel A. Fleisch(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Or you can point your right index finger in the direction of the first vector and your right middle finger in the direction of the second vector. Whether you use the pushing, curling, or pointing approach, your right thumb shows you the direction of the cross product. 2.2 Cross product 29 A A × B Plane containing both A and B A B B A × B θ Figure 2.2 Direction of the cross product A × B . B The length of the cross product equals the area of the parallelogram formed by vectors A and B Parallelogram A × B Height is | B |sin( θ ) A Plane containing both A and B θ Figure 2.3 The cross product as area. since the negative of a vector is just a vector of the same magnitude in the opposite direction. A quick method of computing the magnitude of the cross product is to use | A × B | = | A || B | sin (θ), (2.8) where | A | is the magnitude of A , | B | is the magnitude of B , and θ is the angle between A and B . 3 One way to picture the length and direction of the cross product is illustrated in Figure 2.3 . Just as the dot product involves the projection of one vector onto another, the cross product also has a geometrical interpretation. In this case, the magnitude of the cross product between two vectors is proportional to the area of the parallelogram formed with those two vectors as adjacent sides. As you may recall, the area of a parallelogram is just its base times its height, and 3 The equivalence of Eq. 2.8 and the magnitude of the expression in Eq. 2.5 is demonstrated in the problems at the end of this chapter. 30 Vector operations in this case the height of the parallelogram is | B | sin (θ) and the length of the base is | A | . That makes the area of the parallelogram equal to | A || B | sin (θ) , exactly as given in Eq. 2.8 . So if the angle between two vectors A and B is zero or 180 ◦ (that is, if A and B are parallel or antiparallel), the cross product between them is zero. - eBook - PDF

- Lawrence Turyn(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

6 Geometry, Calculus, and Other Tools 6.1 Dot Product, Cross Product, Lines, and Planes In this chapter, we study many geometric and differential calculus results that have many useful and powerful applications to problems of engineering and science. 6.1.1 Dot Product and Cross Product We have been using the dot product, which is familiar also from its physical applications. For example, the work , W , is given by W = F • u || F || || u || cos θ , where F is a constant force u is the displacement θ is the angle between the vectors F and u satisfying 0 ≤ θ ≤ π . Algebraically, for two vectors r 1 , r 2 in R 3 , r 1 • r 2 = ⎡ ⎣ x 1 y 1 z 1 ⎤ ⎦ • ⎡ ⎣ x 2 y 2 z 2 ⎤ ⎦ = x 1 x 2 + y 1 y 2 + z 1 z 2 . Denote ˆ ı ⎡ ⎣ 1 0 0 ⎤ ⎦ , ˆ j ⎡ ⎣ 0 1 0 ⎤ ⎦ , ˆ k ⎡ ⎣ 0 0 1 ⎤ ⎦ . (6.1) The cross product between vectors r 1 = x 1 ˆ ı + y 1 ˆ j + z 1 ˆ k and r 2 = x 2 ˆ ı + y 2 ˆ j + z 2 ˆ k is defined by r 1 × r 2 = ˆ ı ˆ j ˆ k x 1 y 1 z 1 x 2 y 2 z 2 = y 1 z 1 y 2 z 2 ˆ ı − x 1 z 1 x 2 z 2 ˆ j + x 1 y 1 x 2 y 2 ˆ k = ( y 1 z 2 − z 1 y 2 ) ˆ ı + ( z 1 x 2 − x 1 z 2 ) ˆ j + ( x 1 y 2 − y 1 x 2 ) ˆ k . 457 458 Advanced Engineering Mathematics Theorem 6.1 (Properties of the cross product) (a) x × y is perpendicular to both x and y . (b) || x × y || = || x || || y || sin θ , where θ is the angle between the vectors x and y such that 0 ≤ θ ≤ π . (c) x × y = 0 if, and only if, { x , y } is linearly dependent, that is, x and y are parallel or one of them is the zero vector. (d) y × x = − x × y . (e) ˆ ı × ˆ j = ˆ k , ˆ j × ˆ k = ˆ ı , ˆ k × ˆ ı = ˆ j . (f) ˆ ı × ˆ ı = 0 , ˆ j × ˆ j = 0 , ˆ k × ˆ k = 0 . Example 6.1 A force F acting on a lever arm at a position r relative to an axis applies the torque τ r × F , as depicted in Figure 6.1. Example 6.2 A charge q moving with a velocity v in a magnetic flux density B experiences the Lorentz force F = q v × B . Example 6.3 Find a unit vector normal to both of the vectors r 1 = ˆ ı + 2 ˆ j + 3 ˆ k , and r 2 = ˆ j − ˆ k . - eBook - PDF

- Morton E. Gurtin, Eliot Fried, Lallit Anand(Authors)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

The term point will be reserved for elements of E and the term vector for elements of the associated vector space V . Then: (i) The difference v = y − x between the points y and x is a vector. (ii) The sum y = x + v of a point x and a vector v is a point. (iii) Unlike the sum of two vectors, the sum of two points has no meaning. 1.1 Inner Product. Cross Product Our assumption that the point space E be Euclidean automatically endows the asso-ciated vector space V with an inner product. 3 We use the standard notation of vector analysis. In particular, • The inner product (a scalar) and cross product (a vector) 4 of vectors u and v are respectively designated by u · v and u × v . 3 The inner product is often referred to as the dot product. 4 We assume that the reader has some familiarity with these notions. The cross product is ordered in the sense that the cross product u × v of u and v is not generally equal to the cross product v × u of v and u . 3 4 Vector Algebra Figure 1.1. The parallelogram P defined by the vectors u and v and the direction of u × v determined by the right-hand screw rule. The inner product determines the magnitude (or length) of a vector u via the relation | u | = √ u · u ; and the angle θ = ∠ ( u , v ) (1.1) between nonzero vectors u and v is defined by cos θ = u · v | u || v | (0 ≤ θ ≤ π ) . (1.2) Since −| u || v | ≤ u · v ≤ | u || v | , this definition assigns exactly one angle θ to each pair of nonzero vectors u and v . Trivially, u · v = | u || v | cos θ ; this relation is often used to define the inner product. With regard to the cross product, the magnitude | u × v | (1.3) represents the area spanned by the vectors u and v ; that is, the area of the parallelogram P defined by these vectors as indicated in Figure 1.1 ; this area is nonzero if and only if u and v are linearly independent . - No longer available |Learn more

Mathematical Physics

An Introduction

- Derek Raine(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Mercury Learning and Information(Publisher)

The introduction of a set of basis vectors provides the crucial link between the geometrical picture of a vector (an object with magnitude and direction) and the algebra of vectors (objects formed from linear combinations of the basis vectors). By passing between the two approaches we can formulate a problem in geometric terms, solve it using algebra and then return to a geometric picture, if that is appropriate. We shall see many examples of this in what follows: it is one of the reasons why vectors are so useful in physical science.4.3.THE SCALAR (DOT) PRODUCT

We have seen how to add vectors both geometrically and in terms of a basis, and we have seen how to multiply a vector by a scalar but so far we have given no meaning to multiplying vectors.We are free to choose a definition for the product of two vectors, but if the resulting construct is to have any use it must correspond to some geometrical operation on directed line segments. It turns out that there are two such operations. The first of these is called the scalar or “dot” product and is defined here. Later we shall meet another product called the vector product. These are the only two meaningful ways of multiplying vectors. (Actually there is another, called the tensor product, but that will not concernus here.)Definition: Let θ be the angle between the two vectors a and b . The scalar product (or “dot product”) of two vectors a and b , written a · b , is defined to be the number |a ||b | cos(θ ):Note that the definition implies the important resulta · a = |a |2 .Notice that the scalar product takes two vectors and produces one scalar (a number). Also notice, from the definition (Equation 4.5),that the scalar product is commutative:(the order of the two vectors in the scalar product does not affect the result).If is a vector of unit length making an angle θ with a vector v, thenis the (orthogonal) projection of v on (see Figure 4.4 ). In Section 4.9 we shall find an alternative expression for the projection of one vector on another that does not explicitly involve the angle θ - eBook - PDF

Calculus

Multivariable

- William G. McCallum, Deborah Hughes-Hallett, Andrew M. Gleason, David O. Lomen, David Lovelock, Jeff Tecosky-Feldman, Thomas W. Tucker, Daniel E. Flath, Joseph Thrash, Karen R. Rhea, Andrew Pasquale, Sheldon P. Gordon, Douglas Quinney, Patti Frazer Lock(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Imagine the two vectors v and w as two metal rods welded together. Attach a third rod whose direction and length correspond to v × w . (See Figure 13.37.) Then, no matter how we turn this set of rods, the third will still be the cross product of the first two. The algebraic definition is more easily remembered by writing it as a 3 × 3 determinant. (See Appendix E.) v × w = i j k v 1 v 2 v 3 w 1 w 2 w 3 = (v 2 w 3 − v 3 w 2 ) i + (v 3 w 1 − v 1 w 3 ) j + (v 1 w 2 − v 2 w 1 ) k . Example 1 Find i × j and j × i . Solution The vectors i and j both have magnitude 1 and the angle between them is π/2. By the right-hand rule, the vector i × j is in the direction of k , so n = k and we have i × j = ‖ i ‖‖ j ‖ sin π 2 k = k . Similarly, the right-hand rule says that the direction of j × i is − k , so j × i = (‖ j ‖‖ i ‖ sin π 2 )(− k ) = − k . 764 Chapter Thirteen A FUNDAMENTAL TOOL: VECTORS Similar calculations show that j × k = i and k × i = j . Example 2 For any vector v , find v × v . Solution Since v is parallel to itself, v × v = 0 . Example 3 Find the cross product of v = 2 i + j − 2 k and w = 3 i + k and check that the cross product is perpendicular to both v and w . Solution Writing v × w as a determinant and expanding it into three two-by-two determinants, we have v × w = i j k 2 1 −2 3 0 1 = i 1 −2 0 1 − j 2 −2 3 1 + k 2 1 3 0 = i (1(1) − 0(−2)) − j (2(1) − 3(−2)) + k (2(0) − 3(1)) = i − 8 j − 3 k . To check that v × w is perpendicular to v , we compute the dot product: v · (v × w ) = (2 i + j − 2 k ) · ( i − 8 j − 3 k ) = 2 − 8 + 6 = 0. Similarly, w · (v × w ) = (3 i + 0 j + k ) · ( i − 8 j − 3 k ) = 3 + 0 − 3 = 0. Thus, v × w is perpendicular to both v and w .

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.