What is Political Economy?

MA, Sociology (Freie Universität Berlin)

Date Published: 20.04.2023,

Last Updated: 14.11.2023

Share this article

Defining political economy

Political economy is a dynamic and evolving discipline. It began during the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century with the work of classical economists including Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Thomas Malthus. Much of their ideas, such as the notion that the market is governed by an invisible hand, are likely to sound familiar. According to these tenets of liberal economic thought, the government ought to take a laissez-faire approach by intervening as little as possible. This way, the laws of the market – such as the balance of supply and demand – can help return fluctuations in the economy back to equilibrium.

Looking at a passage from Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations (1776, [2021]), we can see how these laws are described in almost biblical proportions,

[The Rich] are led by an invisible hand to make nearly the same distribution of the necessaries of life, which would have been made, had the earth been divided into equal portions among all its inhabitants, and thus without intending it, without knowing it, advance the interest of the society, and afford means to the multiplication of the species. When Providence divided the earth among a few lordly masters, it neither forgot nor abandoned those who seemed to have been left out in the partition.

Adam Smith

[The Rich] are led by an invisible hand to make nearly the same distribution of the necessaries of life, which would have been made, had the earth been divided into equal portions among all its inhabitants, and thus without intending it, without knowing it, advance the interest of the society, and afford means to the multiplication of the species. When Providence divided the earth among a few lordly masters, it neither forgot nor abandoned those who seemed to have been left out in the partition.

For Smith and his ilk, the market is ahistorical. As if originating in the book of Genesis, he describes the rich and the poor as simply having been preordained to their stations rather than interrogating why this social order exists in the first place. Even today, the foundational principles of classical economics are often taken for granted – as if they were simply born out of the natural order of things.

There was, however, one noteworthy philosopher who was unsatisfied by what the classical economists had surmised. This man was Karl Marx, German philosopher and economist (see ‘What is Marxism?’). Marx was a dedicated dialectical materialist – a method for understanding social phenomena that has become a guiding principle in the field of political economy. Dialectical materialism starts from the stance that,

The whole world, natural, historical, intellectual, is represented as a process – i.e., as in constant motion, change, transformation, development; and the attempt is made to trace out the internal connection that makes a continuous whole of all this movement and development. (Friedrich Engels, 1880 [2012])

Friedrich Engels

The whole world, natural, historical, intellectual, is represented as a process – i.e., as in constant motion, change, transformation, development; and the attempt is made to trace out the internal connection that makes a continuous whole of all this movement and development. (Friedrich Engels, 1880 [2012])

By analyzing the economy through this more holistic analytical lens, Marx argued that the free market emerged out of clear historical processes driven by conflicts between countervailing forces rather than taking its principles as a given. Pulling just a few relevant findings from his dialectical method, we can begin to understand the evolution of political economic thought.

For one, Marx situated the emergence of the market economy within a clear historical context. He asserted that it was ushered in through conscious policy interventions and violent struggles that left peasants dispossessed from the land and, therefore, denied access to provisions they needed to live.

The great English landowners dismissed their retainers … [and] their tenants chased off their smaller cottagers etc., then, firstly, a mass of living labour powers were thrown upon the labour market, a mass which was free in the double sense, free from the old relations of clientship, bondage and servitude, and secondly free of all belongings and possessions … free of all property; dependent on the sale of its labour capacity or on begging, vaga-bondage or robbery as its only source of income. (Marx, cited by David Harvey in A Companion to Marx's Grundrisse, 2023)

David Harvey

The great English landowners dismissed their retainers … [and] their tenants chased off their smaller cottagers etc., then, firstly, a mass of living labour powers were thrown upon the labour market, a mass which was free in the double sense, free from the old relations of clientship, bondage and servitude, and secondly free of all belongings and possessions … free of all property; dependent on the sale of its labour capacity or on begging, vaga-bondage or robbery as its only source of income. (Marx, cited by David Harvey in A Companion to Marx's Grundrisse, 2023)

He argued this was the origin story of the economy, which he termed primitive accumulation. Thus, in Marx’s view, the poor were forced to sell their labor as a result of specific historical developments. This runs in contrast to Adam Smith’s view that society had been divided into the rich and the poor since the dawn of time, and that this order of things was driven by some sort of invisible hand.

Moreover, instead of being a self-regulating sphere independent from other areas of life, Marx asserted that capitalism had fundamentally altered society as it had become reorganized in service of accumulating ever more capital. Marx writes that “capital creates the bourgeois society”, and that:

For the first time, nature becomes purely an object for humankind [...] and the theoretical discovery of its autonomous laws appears merely as a ruse so as to subjugate it under human needs, whether as an object of consumption or as a means of production. (Marx, cited by John Bellamy Foster in Karl Marx’s Grundrisse, 2008)

Edited by Marcello Musto

For the first time, nature becomes purely an object for humankind [...] and the theoretical discovery of its autonomous laws appears merely as a ruse so as to subjugate it under human needs, whether as an object of consumption or as a means of production. (Marx, cited by John Bellamy Foster in Karl Marx’s Grundrisse, 2008)

Capitalism’s division of people into those who own the means of production and the masses who were forced to sell their labor for wages was a topic of major concern for Marx. In turn, his successors in the field of political economy have expanded upon how the conversion of the majority of people into wage laborers under capitalism has significant implications. From the role of the state to our identities and social relationships, much of the discipline of political economy explores the interplay between the market and the way we live our lives.

Political economy: the market and the modern state

As evidenced in the name of the discipline, political economists are particularly concerned with a conception of capitalism that jointly comprises an economic sphere and a political one. Following Marxian thought on primitive accumulation, they argue that the modern state emerged alongside the market economy. They contend that the two exist in a dialectical relationship to one another in the sense that they are interconnected but oftentimes also at odds. Such is evidenced by the work of Karl Polanyi, who is considered both an heir to and critic of Marxist thought in his writings about the nature and role of the modern state apparatus within capitalist societies.

Karl Polanyi’s thoughts on fictitious commodities and market societies

Polanyi’s work begins with an expansion on Marx’s concept of the commodity. For Marx, in simplest terms, commodities are objects created in the sphere of production (e.g. in factories) and then sold to consumers for a profit. The thing that makes the commodity worth more than the raw materials that went into their creation is the amount of human labor that was required in their production (Marx, Das Kapital, 1867, [2012]). Because labor power itself is treated as a commodity in the sense that it is sold by the worker and bought by the capitalist within the sphere of production, Marx emphasized that it was peculiar in nature (see also “What is Commodity Fetishism?”). This is because human life is not produced by the same mechanisms as other commodities nor is it inherent to capitalist economies. As Marx explains,

One consequence of the peculiar nature of labor-power as a commodity is that its use-value does not, on the conclusion of this contract between the buyer and seller, immediately pass into the hands of the former. Its value, like that of every other commodity, is already fixed before it goes into circulation, since a definite quantity of social labor has been spent upon it; but its use-value consists in the subsequent exercise of its force. The alienation of labor-power and its actual appropriation by the buyer, its employment as a use-value, are separated by an interval of time. But in those cases in which the formal alienation by sale of the use-value of a commodity is not simultaneous with its actual delivery to the buyer, the money of the latter usually functions as means of payment. (Marx, Das Kapital, 1867, [2012])

Karl Marx

One consequence of the peculiar nature of labor-power as a commodity is that its use-value does not, on the conclusion of this contract between the buyer and seller, immediately pass into the hands of the former. Its value, like that of every other commodity, is already fixed before it goes into circulation, since a definite quantity of social labor has been spent upon it; but its use-value consists in the subsequent exercise of its force. The alienation of labor-power and its actual appropriation by the buyer, its employment as a use-value, are separated by an interval of time. But in those cases in which the formal alienation by sale of the use-value of a commodity is not simultaneous with its actual delivery to the buyer, the money of the latter usually functions as means of payment. (Marx, Das Kapital, 1867, [2012])

To make sense of what this means, let’s look at a real-life example. In the eyes of a restaurant owner, when a cook clocks into her shift, her labor power is treated as another necessary ingredient in the making of each dish which is sold that night for a profit. In fact, according to Marx’s argument, her labor is the main element that makes the meat, vegetables, and grains into something more profitable than the sum of their parts. In that sense, labor is a commodity because it is treated as such in the sphere of production. Yet, of course, the labor used to produce value is not simply a commodity to be bought like other restaurant supplies, but instead is performed by a human being who clocks out of the restaurant at the end of every shift. Thus, Marx regards labor as a peculiar commodity because human beings cannot merely be reduced to their commodity form, as they lead complex and multifaceted lives outside of the workplace.

In his book, The Great Transformation (1944), Polanyi takes Marx’s labor theory of value as his starting point but brings it a step further in his ethnographic studies of early capitalist societies. What he found is that in addition to labor power, both land and money were essential to both establishing and maintaining market economies. He termed these “fictitious commodities” since they were not actually produced like other commodities, but were treated as such within market societies.

For Polanyi, this had striking implications. Firstly, it showed that the market was not truly a closed circuit independent from other spheres of life, but was fundamentally dependent on things external to it. Furthermore, through the commodification of nature, people, and money, he observed that the unprecedented centrality of the market subordinated the rest of the society to it. He also deduced that the modern state as we have come to know it today emerged alongside the market economy precisely in order to facilitate these forms of commodification. In Karl Polanyi (2013), Gareth Dale states:

Although in theory a self-regulating mechanism, there was nothing natural about free market capitalism; a system of that sort “could never have come into being merely by allowing things to take their course”. Instead, the road to it “was opened and kept open by an enormous increase in continuous, centrally organized and controlled interventionism” – including the French Revolution, and the Poor Law Reform and associated Benthamite initiatives of the 1830s–40s.

Gareth Dale

Although in theory a self-regulating mechanism, there was nothing natural about free market capitalism; a system of that sort “could never have come into being merely by allowing things to take their course”. Instead, the road to it “was opened and kept open by an enormous increase in continuous, centrally organized and controlled interventionism” – including the French Revolution, and the Poor Law Reform and associated Benthamite initiatives of the 1830s–40s.

As such, the modern state was actually charged with facilitating the great transformation of the pre-capitalist world into market societies. Like Marx, Polanyi vehemently argued that laissez faire was an ideological myth. Moreover, Polanyi believed that the state and the economy continually were intertwined in a dialectical “double movement” wherein the political sphere simultaneously was charged with facilitating the conditions necessary for capital accumulation whilst simultaneously constraining some of its more unbridled expansionist tendencies. Thus, at times, the state was also tasked with saving capitalism from itself.

There is the linked notion that the aim of increasing wealth through constructing a “pure” market society would prove to be a Faustian bargain, as it licenses a set of motivations and values that contribute to the ruination of the society in which they prevailed [...] the commodification of land, labour and money results in social disintegration, compelling “society” to protect itself by delegating the state to regulate fictitious commodities. (Dale, 2013)

As an advocate of the welfare state model during the Fordist period in which he was writing, Polanyi argued that the market society functioned best when the state intervened to regulate the economy through corporate taxation, price regulation, and public spending projects that maintained high levels of employment.

Polanyi argues that the effects of the marketization of these fictitious commodities produced social “countermovement” of one sort or another designed to mitigate or offset these harms by interfering with the principle of market self-regulation, a process he sometimes describes as the “protection of society” (Dale, 2013).

Polanyi offers just one example of how political economists expand our understanding of what constitutes capitalism beyond the economic sphere. How the dialectical tensions between the economy and the state serve to drive policy at different junctures of history is of critical importance to the discipline, but political economists don’t stop there. As Polanyi aptly terms it the market society, political economists are also concerned with the ways in which market principles have infiltrated our very relationships, identities, and desires. For this, we will now turn to the works of social reproduction theorists.

Political economy: capitalism, gender, and intersectionality

As a central component of market societies, political economists are concerned with the ways in which the introduction of wage labor under capitalism has fundamentally altered the way we structure our lives. Most people today must sell their labor power in return for wages in order to buy the goods they need to live. This market dependence is necessary for the capitalist mode of production because otherwise there would be little to no motivation to organize so much of our lives around wage labor. Nor would the economy be able to function if it weren’t for workers' continuous supply of labor power. As Marx puts it in dialectical terms,“every social process of production is, at the same time, a process of reproduction” (Marx, Das Kapital, 1867, [2012]).

Thus, the fulfillment of workers’ needs becomes a constituent part of capitalism as a totality. Yet, Marx spends far more time attending to the sphere of production and comparatively little on exploring the sphere of reproduction.

This is where political economists have intervened in the development of Social Reproduction Theory. As Tithi Bhattacharya explains, at its most basic level,

One understanding of social reproduction is that it is about two separate spaces and two separate processes of production: the economic and the social—often understood as the workplace and home. In this understanding, the worker produces surplus value at work and hence is part of the production of the total wealth of society. At the end of the workday, because the worker is “free” under capitalism, capital must relinquish control over the process of regeneration of the worker and hence the reproduction of the workforce. (2017)

Edited by Tithi Bhattacharya

One understanding of social reproduction is that it is about two separate spaces and two separate processes of production: the economic and the social—often understood as the workplace and home. In this understanding, the worker produces surplus value at work and hence is part of the production of the total wealth of society. At the end of the workday, because the worker is “free” under capitalism, capital must relinquish control over the process of regeneration of the worker and hence the reproduction of the workforce. (2017)

In reality, the list of dimensions to social reproduction is quite lengthy. It includes all those things necessary to reproduce the worker both from the day-to-day and generationally. In terms of the former, it includes both subsistence needs such as food, clothing, and shelter as well as higher needs associated with personal development and emotional fulfillment. In terms of the latter, it involves all that goes into raising children who will grow up to be good and compliant workers.

You may notice that many of these topics touch upon gendered forms of labor such as nurturance, child rearing, housework, emotional labor, and other forms of care. Indeed, social reproduction has been an object of interest particularly among Marxist feminists (see “What is Marxist feminism?”). They argue that these forms of unpaid or informal labor that occur outside the sphere of production are just as essential to capitalism’s functioning as more traditional ideas of wage labor in factories or mines or offices. According to social reproduction theorists then, it is this totality of different kinds of labor – both waged and unwaged – that constitute capitalism:

[I]n capitalist societies the majority of people subsist by combining paid employment and unpaid domestic labor to maintain themselves . . . [hence] this version of social reproduction analyzes the ways in which both labors are part of the same socio-economic process. (Kate Bezanson and Meg Luxton, cited by Bhattacharya, 2017)

Today, many women are responsible not only for their day jobs but also for second and third shifts of unpaid housework and childcare.

Based on their rootedness in Marxian political economy, social reproduction theorists also advocate for a revised outlook on intersectional feminism. For social reproduction theorists, class, gender, and race are not separate categories that intersect with one another to form one’s identity. Rather, they argue that gendered and racial oppression as we have come to experience them today have emerged out of market societies.

Closing thoughts

Political economy is a discipline that uses the dialectical method to understand capitalism in its totality. It is a school of thought broadly inherited from the work of Karl Marx in critiquing what he regarded to be the classical economists’ incomplete thinking about the free market. In particular, political economists push back against the notion of the economy as a self-regulating sphere governed by metaphysical laws and instead understand it to be part of a larger social order that is upheld by numerous other facets of society.

Thus, as Nancy Fraser puts it in her book, Capitalism: A Conversation in Critical Theory (2018), for political economists, “capitalism is best conceived neither as an economic system nor as a reified form of ethical life, but rather as an institutionalized social order, on a par with feudalism.” Political economists argue, therefore, that capitalism is a system that includes a wider set of institutions ranging from the government to the family – which have all been reoriented towards the accumulation of capital. From this conception of capitalism, political economists have continued to excavate and expand on Marx’s writings.

Today, political economy comprises an interdisciplinary roster of scholars ranging from political theorists like Nancy Fraser to geographers like David Harvey and Ruth Wilson Gilmore. Respectively, they draw upon Marx’s dialectical method to demonstrate how the contradictions of capitalism produce social crises, shape urban life, and underpin the expansion of the prison industrial complex. Moreover, through a broader conception of capitalism consisting of spheres of production and reproduction, theorists like Tithi Bhattacharya illustrate how class society itself produces and reinforces myriad forms of social inequality including racism and sexism. In these ways and more, Marx’s legacy provides political economists with a holistic method for exposing the material conditions that shape all spheres of life under capitalism.

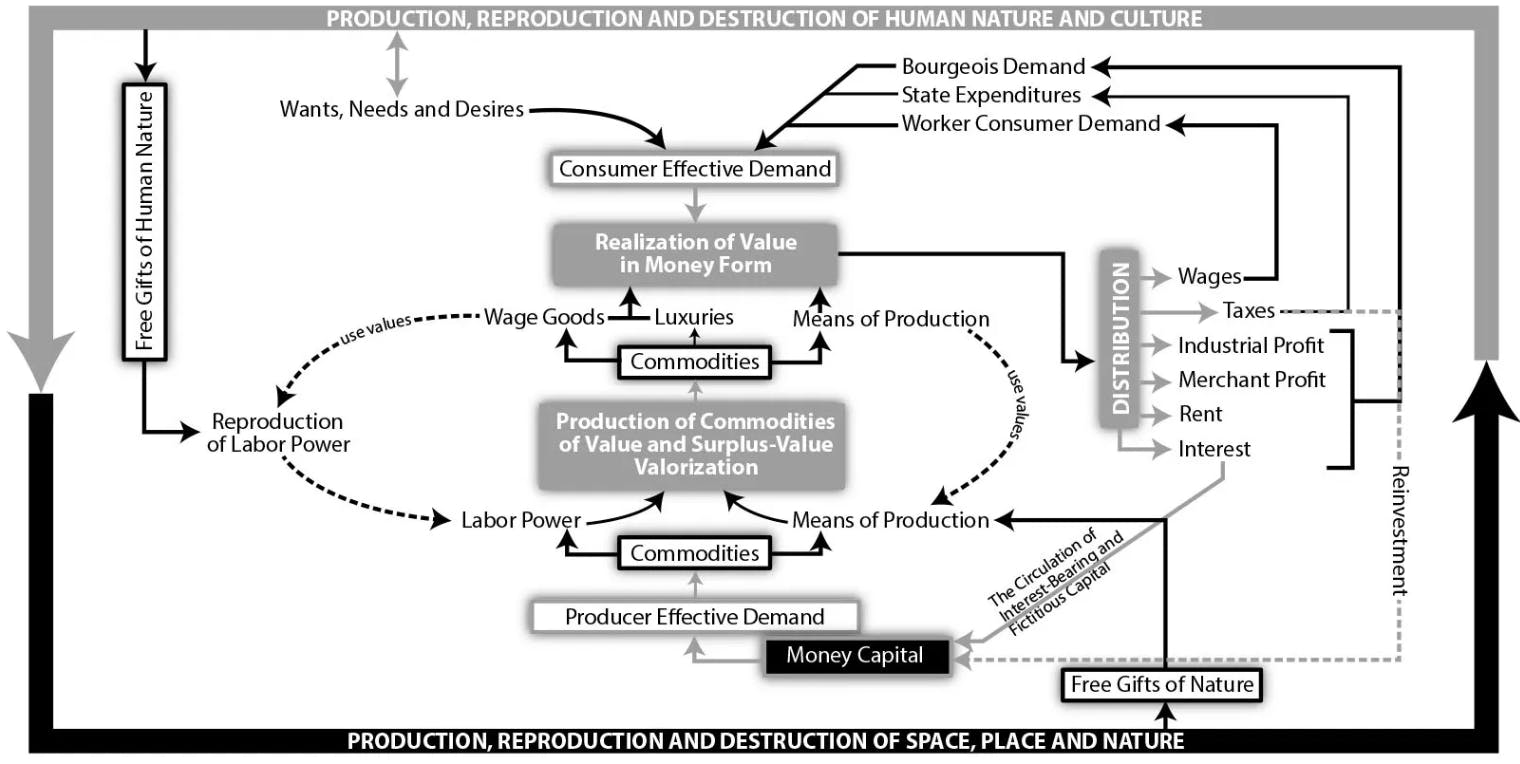

The above diagram offers a visual representation of what comprises capitalism according to political economy. (From A Companion to Marx’s Grundrisse by David Harvey, 2023)

Further reading on Perlego

Eltis, W. (2016) The Classical Theory of Economic Growth. Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3499221/the-classical-theory-of-economic-growth-pdf

Harvey, D. (2018) A Companion To Marx's Capital. Verso. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/827854/a-companion-to-marxs-capital-the-complete-edition-pdf

Lebowitz, M. (2003) Beyond Capital: Marx’s Political Economy of the Working Class. Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3496702/beyond-capital-marxs-political-economy-of-the-working-class-pdf

Wilson Gilmore, R. (2022) Abolition Geography. Verso. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3472053/abolition-geography-essays-towards-liberation-pdf

Political economy FAQs

What is political economy in simple terms?

What is political economy in simple terms?

What is an example of political economic theory?

What is an example of political economic theory?

Who are scholars associated with political economy?

Who are scholars associated with political economy?

Bibliography

Bhattacharya, T. (ed.) (2017) Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression. Pluto Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/665246/social-reproduction-theory-remapping-class-recentering-oppression-pdf

Dale, G. (2013) Karl Polanyi: The Limits of the Market. John Wiley & Sons. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1535100/karl-polanyi-the-limits-of-the-market-pdf

Dale, G., Holmes, C., and Markantonatou, M. (eds.) (2019) Karl Polanyi’s Political and Economic Thought: A Critical Guide. Agenda Publishing. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1100155/karl-polanyis-political-and-economic-thought-a-critical-guide-pdf

Engels, F. (2012) Socialism Utopian and Scientific. Trans. E. Aveling. Perlego. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1820308/socialism-utopian-and-scientific-pdf

Fraser N., Jaeggi, R. and Milstein, B. (2018) Capitalism: A Conversation in Critical Theory. Polity. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1536438/capitalism-a-conversation-in-critical-theory-pdf

Harvey, D. (2023) A Companion to Marx’s Grundrisse. Verso Books. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3814944/a-companion-to-marxs-grundrisse-pdf

Marx, K. (1867 [2012]) Das Kapital. Gateway Editions. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/784600/das-kapital-a-critique-of-political-economy-pdf

Musto, M. (ed.) (2008) Karl Marx’s Grundrisse. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/717802/karl-marxs-grundrisse-pdf

Smith, A. (2021) The Wealth of Nations. Icarsus. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2628240/wealth-of-nations-pdf

MA, Sociology (Freie Universität Berlin)

Lily Cichanowicz has a master's degree in Sociology from Freie Universität Berlin and a dual bachelor's degree from Cornell University in Sociology and International Development. Her research interests include political economy, labor, and social movements. Her master's thesis focused on the labor shortages in the food service industry following the Covid-19 pandemic.