What is Ergodic Literature?

PhD, English Literature (Lancaster University)

Date Published: 22.01.2024,

Last Updated: 30.01.2024

Share this article

Definition and origins

Ergodic literature is a term first introduced to Espen J. Aarseth in Cybertext (1997), describing literature in which a “nontrivial effort is required to allow the reader to traverse the text.” Aarseth distinguishes this from “nonergodic literature” in which accessing the text requires no more than “eye movement or the periodic or arbitrary turning of pages” (1997).

The word “ergodic” comes from the Greek words “ergon” (meaning work) and “hodos” (meaning path). Translated literally, it means the reader must work to travel through the text. Ergodic literature may employ a range of different methods to the reading process; such as adding puzzles, making the reader jump forwards and backwards through the pages, as well as unusual formatting or spacing of the text on the page. A key example of ergodic literature is Hopscotch (1963) by Julio Cortazar, a novel split into three groups of chapters: chapters 1-36 entitled “From the Other Side,” chapters 37-56 entitled “From this Side,” and the final chapters entitled “Expendable chapters.” These latter “expendable” chapters often fill in information missing in the main narrative. At the start of the novel, Cortazar provides a table of contents with instructions on how to read the book, also offering the reader a choice in how they complete the narrative. When reading Hopscotch, the reader must consult instructions and decide on how they want to engage with the story.

The array of choice, fragmentation, and non-linearity found in Hopscotch are core elements inherent to the experience of reading ergodic literature. This is distinct from non-ergodic, or traditional, literature in which the method of reading the text is clear. Even in nonlinear, non-ergodic fiction, it is clear that the reader must go through the pages in sequence and every reader will have access to the same text, even if their interpretations differ.

As Markku Eskelinen writes,

in ergodic literature there are other necessary tasks for the user in addition to mere interpretation, and there necessarily exists a feedback loop between the user and the text. Traditional problems of literary theory and interpretation are not foregrounded in Cybertext, as the focus of Aarseth’s theory is on textonomy (the study of the textual medium) rather than on textology (the study of the textual meaning). (Cybertext Poetics, 2012)

Markku Eskelinen

in ergodic literature there are other necessary tasks for the user in addition to mere interpretation, and there necessarily exists a feedback loop between the user and the text. Traditional problems of literary theory and interpretation are not foregrounded in Cybertext, as the focus of Aarseth’s theory is on textonomy (the study of the textual medium) rather than on textology (the study of the textual meaning). (Cybertext Poetics, 2012)

An important subcategory of ergodic literature is the cybertext. Cybertexts are a type of ergodic literature that requires calculations for the text to be accessed or understood. These calculations can either be done by a computer system, such as a chatbot, or by the reader. An example of the latter form is the I Ching, or the Book of Changes, a divination book that requires the reader to perform calculations in order to traverse the text. We will explore the I Ching further in this guide. This differentiates cybertexts from other forms of ergodic literature in which calculations do not need to be performed, such as with Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves which experiments with typography and formatting, but does not require the reader to decipher any particular kind of code and does not have dynamically changing storylines based on the reader’s input.

As Jouni Smed et al summarise:

Cybertexts belong to the ergodic literature, but they require calculation – usually by a computer – to produce the text. An important feature of the cybertext is that it keeps reminding the reader of the consequences of their choices: there are paths they have not taken – which might have even become inaccessible to them. (Handbook of Interactive Storytelling, 2021)

Jouni Smed et al

Cybertexts belong to the ergodic literature, but they require calculation – usually by a computer – to produce the text. An important feature of the cybertext is that it keeps reminding the reader of the consequences of their choices: there are paths they have not taken – which might have even become inaccessible to them. (Handbook of Interactive Storytelling, 2021)

It is important to note that ergodic literature simply refers to texts in which the intended method of reading is not obvious and where the reader can choose how to approach the text; it does not describe how readers interpret the text. Nor does ergodic literature refer to simply nonlinear narratives. Literary critics took issue with Aarseth’s distinguishing of ergodic and nonergodic literature as “they claimed that all texts are produced as a linear sequence during reading” (1997). However, as Aarseth clarifies:

The problem was that, while they focused on what was being read, I focused on what was being read from. [...] when you read from a cybertext, you are constantly reminded of inaccessible strategies and paths not taken, voices not heard. Each decision will make some parts of the text more, and others less, accessible, and you may never know the exact results of your choices; that is, exactly what you missed. This is very different from the ambiguities of a linear text. (1997)

The reader is thus empowered through their role as a decision-maker and collaborator in the creation of the text. In “Secrecy and Community in Ergodic Texts,” Derek Attridge writes,

Being able to decide when to look at an illustration or a footnote, which thread to follow in a set of parallel narratives or how to treat spatial arrangements that complicate linearity are all ways in which the reader’s freedom is enhanced. Making these choices impacts upon the experience of the novel as a narrative, of course, but the very fact of being given the choice is itself part of the experience that renders a given work singular. And if the ergodic dimension of such texts can be thought of as operating to some extent independently of the text’s meanings, constituting no part of the content that could be captured in a paraphrase, it could be said to operate in secret. (Secrecy and Community in 21st-Century Fiction, 2021)

Edited by María J. López and Pilar Villar-Argáiz

Being able to decide when to look at an illustration or a footnote, which thread to follow in a set of parallel narratives or how to treat spatial arrangements that complicate linearity are all ways in which the reader’s freedom is enhanced. Making these choices impacts upon the experience of the novel as a narrative, of course, but the very fact of being given the choice is itself part of the experience that renders a given work singular. And if the ergodic dimension of such texts can be thought of as operating to some extent independently of the text’s meanings, constituting no part of the content that could be captured in a paraphrase, it could be said to operate in secret. (Secrecy and Community in 21st-Century Fiction, 2021)

This guide will explore some examples of traditional form ergodic literature, such as novels, as well as digital hypertext fiction, and video games to demonstrate the widespread and lasting appeal of this form across different types of media.

Examples of ergodic literature

The following section will explore some key examples of print-based ergodic literature.

The I Ching, or Book of Changes

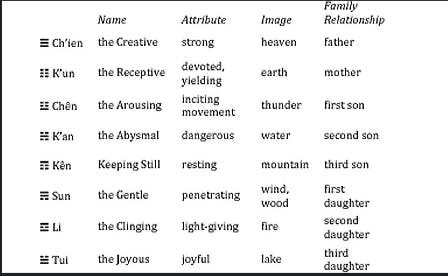

Written around the time of the Western Chou Dynasty (1122-770 B.C.), The I Ching, or Book of Changes is one of the oldest examples of ergodic literature. The Book of Changes is a book of divination and became one of the Five Classics of Confucianism. The linear signs within the book must be decoded by the reader to reveal oracles. The symbols initially were a single unbroken line (meaning “yes”) and a broken line (meaning “no”). However, due to the need for differentiation, the lines were combined into pairs and a third line was added to each combination. From these combinations, eight trigrams were created (Figure 1).

Figure 1, “Eight Trigrams” from Cary F. Baynes and Richard Wilhelm’s translation of The I Ching, or Book of Changes, 2011.

As explained in Richard Wilhelm’s introduction to The Book of Changes,

These eight trigrams were conceived as images of all that happens in heaven and on earth. At the same time, they were held to be in a state of continual transition, one changing into another, just as transition from one phenomenon to another is continually taking place in the physical world. (2011)

Translated by Cary F. Baynes and Richard Wilhelm

These eight trigrams were conceived as images of all that happens in heaven and on earth. At the same time, they were held to be in a state of continual transition, one changing into another, just as transition from one phenomenon to another is continually taking place in the physical world. (2011)

Different combinations of these eight trigrams were used to predict the future of the reader. One method of reading the I Ching is through the coin method: a pair of coins is tossed; each ‘head’ is worth a value of 3 and each ‘tail’ has a value of 2. These numbers are added up to produce a corresponding line. This process is repeated five times to create a six-line hexagram.

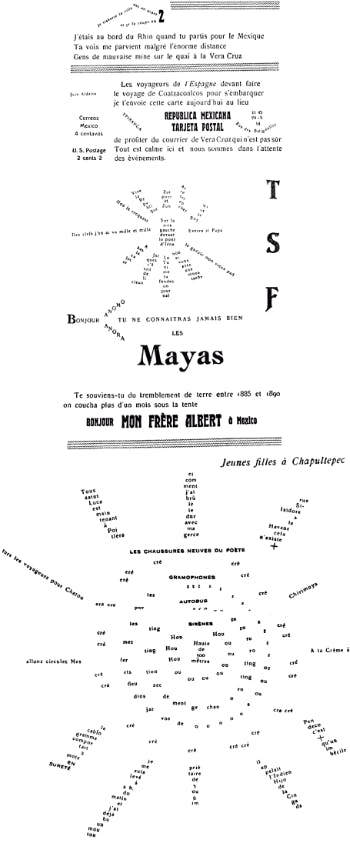

Guillaume Apollinaire

Guillaume Apollinaire was a French poet and playwright, known for his unique and innovative style. In his poetry collection Calligrammes: Poemes de la paix de la guerre (Calligrams) (1913-1916), Apollinaire includes visual poetry, in which the words of the poem are spread out across the page to form an image. There is no clear order in which to read these poems. Apollinaire’s first visual poem, “Lettre-Océan” (“Ocean Letter”), was published in 1914 in Les Soirées de Paris. A “lettre-ocean” was a message transmitted by telegraph between ships at sea. As seen in Figure 2, while certain methods by which to read are fairly obvious (reading left to right), the order in which the poem is meant to be read is ambiguous, particularly regarding the “spokes” patterns.

Figure 2, Guillaume Apollinaire (1914) “Lettre-Océan” Wikimedia Commons, 2013 (used under CC0 1.0)

In Reading Apollinaire's Calligrammes, Willard Bohn explains that

Although the poem includes a few horizontal elements as well, it basically comprises two large wheel-and-spoke patterns. The lines of poetry form a series of concentric circles radiating outward from a circular center, from which extend a number of symmetrical “spokes.” Thus “Lettre-Océan” exploits the physical properties of language to create an ideogrammatic composition in which the formal configuration reinforces the linguistic message and vice versa. (2018)

Willard Bohn

Although the poem includes a few horizontal elements as well, it basically comprises two large wheel-and-spoke patterns. The lines of poetry form a series of concentric circles radiating outward from a circular center, from which extend a number of symmetrical “spokes.” Thus “Lettre-Océan” exploits the physical properties of language to create an ideogrammatic composition in which the formal configuration reinforces the linguistic message and vice versa. (2018)

Apollinaire’s avant-garde visual poetry went on to inspire poets such as E. E. Cummings. Cummings’ poems “ta” and “5” are key examples of ergodic poems in the modernist movement (Tulips & Chimneys, 2019).

House of Leaves

Many postmodernist texts fall into the category of ergodic literature, due to their use of fragmented narratives and temporal disruption. As Regina Schober writes,

There are unmistakable parallels between hypertext and postmodern literature, including the non-linear, interactive, performative, expansive, intertextual, plurivocal, and contingent aesthetics of both. (Spider Web, Labyrinth, Tightrope Walk, 2023)

Regina Schober

There are unmistakable parallels between hypertext and postmodern literature, including the non-linear, interactive, performative, expansive, intertextual, plurivocal, and contingent aesthetics of both. (Spider Web, Labyrinth, Tightrope Walk, 2023)

Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves (2000) is perhaps one of the most well-known and celebrated forms of postmodern, ergodic literature. House of Leaves follows three main storylines all told simultaneously within a frame narrative. The entangled story of the three characters begins when Johnny Truant finds the incomplete manuscript of a now-deceased man named Zampano. The manuscript is an academic study on The Navidson Record, an autobiographical documentary of Will Navidson, a photojournalist. However, Truant can find no record of this footage, except for Zampano’s writings. The documentary Zampano alludes to focuses on Navidson’s experience moving into a new home with his family, a home that transforms over time, with the interior endlessly expanding, creating vast unexplored spaces.

Truant decides to complete and edit Zampano’s study of the Navidson documentary, leaving his commentary or questions in the form of footnotes. The use of footnotes and dual narration already complicates reading this text as the reader must work out or choose which order to read these in. As Aarseth explains,

The footnote is a typical example of a structure that can be seen as both uni- and multicursal. It creates a bivium, or choice of expansion, but should we decide to take this path (reading the footnote), the footnote itself returns us to the main track immediately afterward. (1997)

However, the real challenge of House of Leaves comes from its layout; due to the editorial notes it becomes unclear how to read Danielewski’s text. This stylistic choice places the reader in the position of Truant who too must attempt to decipher the work of Zampano. The layout has an additional purpose: to reflect the spatial disorientation of Navidson and his family; sections of text, much like the rooms in the Navidson home, are not where they should be. Some pages of the work have only one or two words cramped in the corner; sometimes the text spirals and the reader must physically turn the book to continue with the narrative. As A. C. Facundo writes,

The house becomes a metaphor for the novel itself, since the novel is also a “house of leaves” whose interior grows and shrinks according to the reading process. The visual structure of the novel parodies mimetic desire in words. The words on the page visually imitate the architecture of the very house they describe, incorporating size, font, color, and location into their signifying function. Words fall down the page when characters encounter a drop into darkness. They spiral and squeeze through massive margins as characters traverse winding staircases and crawl through cave-like crevices. The word “snaps” becomes the very rope that fails Navidson as its letters scatter across three pages. (Oscillations of Literary Theory, 2016)

A. C. Facundo

The house becomes a metaphor for the novel itself, since the novel is also a “house of leaves” whose interior grows and shrinks according to the reading process. The visual structure of the novel parodies mimetic desire in words. The words on the page visually imitate the architecture of the very house they describe, incorporating size, font, color, and location into their signifying function. Words fall down the page when characters encounter a drop into darkness. They spiral and squeeze through massive margins as characters traverse winding staircases and crawl through cave-like crevices. The word “snaps” becomes the very rope that fails Navidson as its letters scatter across three pages. (Oscillations of Literary Theory, 2016)

In other sections, the layering of text further adds to the sense of disorientation that the reader feels when trying to navigate the work.

What is hypertext fiction?

Choose Your Own Adventure

Hypertext fiction refers to a system of interconnected text(s) where readers can navigate through a series of non-linear paths by clicking on hyperlinks. This allows for readers to choose their own story. One of the most widely quoted definitions of the word “hypertext” comes from Ted Nelson who refers to it as

non-sequential writing - text that branches and allows choices to the reader, best read at an interactive screen. As popularly conceived, this is a series of text chunks connected by links which offer the reader different pathways. (Literary Machines, 1981, [1988])

The Choose Your Own Adventure series, beginning in 1979, is considered a prototype of hypertext. These traditional, paper-based narratives allow readers to choose the main character’s actions at different intervals in the story, ultimately determining the direction of the narrative. These texts paved the way for the digital hypertexts that became popular in the 1980s.

In Electronic Literature, Scott Rettburg identifies some of the defining features of hypertext fiction:

Common characteristics of hypertext fiction include link and node structures, fragmented text, the use of associative logic, alternative narrative structures, complications of character development and chronology, spatialized texts, intertextuality, pastiche and collage, new forms of navigational apparatus, and a focus on interactivity and user choice. (2018)

Scott Rettburg

Common characteristics of hypertext fiction include link and node structures, fragmented text, the use of associative logic, alternative narrative structures, complications of character development and chronology, spatialized texts, intertextuality, pastiche and collage, new forms of navigational apparatus, and a focus on interactivity and user choice. (2018)

A key example of a digital hypertext is Michael Joyce’s “afternoon, a story” (1987–90). In this story, the protagonist Peter has recently witnessed a car crash and suspects, later that day upon reflection, that his ex-wife and son may have been involved in the accident. The story changes depending on the choices made by the reader. You can try to play through the story by clicking on the hyperlink (which requires the use of a browser that is both Java-enabled and Javascript-enabled). Alternatively, you can watch the clip below to see how hyperlinks function in the story.

We can also see how hypertext can be used as an analytical tool to revisit classic literature. In Patchwork Girl (1995), an adaption of Mary Shelley’s classic Frankenstein (1818, [2013]), Shelley Jackson uses a series of images and links to enable the reader to create a unified story. As Anya Heise-von der Lippe writes in Monstrous Textualities

By emphasising the complicated structure of the doubly embedded monster narrative and its abundance of intertextual connections, Jackson’s hypertext novel foregrounds questions about humanity, authority and creation raised by Shelley’s novel and connects them to the critical context of twentieth century feminist readings of the text and its monster. The medium of hypertext, at its best, offers a non-hierarchical, explorative way of conveying knowledge by involving the reader in the creation and piecing-together of narrative elements. (2021)

Anya Heise-von der Lippe

By emphasising the complicated structure of the doubly embedded monster narrative and its abundance of intertextual connections, Jackson’s hypertext novel foregrounds questions about humanity, authority and creation raised by Shelley’s novel and connects them to the critical context of twentieth century feminist readings of the text and its monster. The medium of hypertext, at its best, offers a non-hierarchical, explorative way of conveying knowledge by involving the reader in the creation and piecing-together of narrative elements. (2021)

To see a demonstration of Patchwork Girl, watch the clip below.

Robert Coover expressed concerns about hypertext literature in his New York Times essay “The End of Books” in 1992. The main issues Coover highlights are with navigation and interpretation:

[...] how do you move around in infinity without getting lost? The structuring of the space can be so compelling and confusing as to utterly absorb and neutralize the narrator and to exhaust the reader. And there is the related problem of filtering. With an unstable text that can be intruded upon by other author-readers, how do you, caught in the maze, avoid the trivial? How do you duck the garbage? Venerable novelistic values like unity, integrity, coherence, vision, voice seem to be in danger. Eloquence is being redefined. "Text" has lost its canonical certainty. How does one judge, analyze, write about a work that never reads the same way twice?

In other words, if narratives are dynamic and plot points depend upon the way each reader chooses to navigate the text, how can critics assign value and engage with such works? However, what we have seen, from hypertexts to video games, offering branching options further opens up opportunities for readers to discuss their experiences with the text.

Video games and ergodic media

A large portion of Aarseth’s Cybertext is devoted to discussing how games are a new form of ergodic text. Numerous games enact by their very nature the principles of ergodic literature. In the introduction to The Video Game Theory Reader Mark. J. P. Wolf and Bernard Perron write,

The nature of player activity is also necessarily ergodic (to use Espen Aarseth’s term) or nontrivial and extranoematic, that is, the action has some physical aspect to it and is not strictly an activity occurring purely on the mental plane. (2013)

Edited by Mark. J. P. Wolf and Bernard Perron

The nature of player activity is also necessarily ergodic (to use Espen Aarseth’s term) or nontrivial and extranoematic, that is, the action has some physical aspect to it and is not strictly an activity occurring purely on the mental plane. (2013)

Multi-user dungeons (MUDs) are a prime example of ergodic texts given by Aarseth. MUDs are text-based roleplaying games set in virtual worlds that are accessed by multiple users at a time:

MUDs are effectively online chat sessions with game-play elements and structure; they have multiple places for players to move to and interact in like an adventure game, and may include elements such as combat and traps, as well as puzzles, spells and even simple economics. Early MUDs had text-based interfaces that allowed players to type in basic commands, such as ‘go east’ or ‘open door.’ (Grenville Armitage, Mark Claypool, and Philip Branch, Networking and Online Games, 2006)

Grenville Armitage, Mark Claypool, and Philip Branch

MUDs are effectively online chat sessions with game-play elements and structure; they have multiple places for players to move to and interact in like an adventure game, and may include elements such as combat and traps, as well as puzzles, spells and even simple economics. Early MUDs had text-based interfaces that allowed players to type in basic commands, such as ‘go east’ or ‘open door.’ (Grenville Armitage, Mark Claypool, and Philip Branch, Networking and Online Games, 2006)

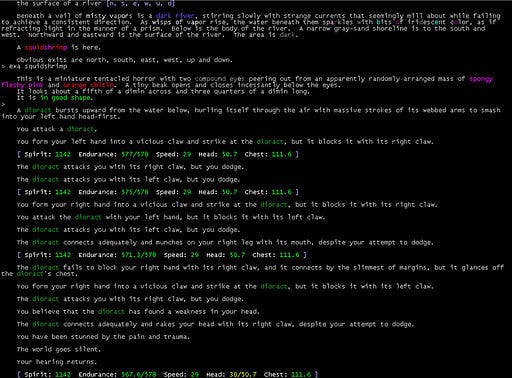

In this sense, MUDs have a similar functionality to in-person RPGs. Figure 5 (a screengrab from the 1990 game Lost Souls) shows what a MUD would appear like to the player.

Figure 5, “Lost Souls screenshot - River Tethys combat,” Wikimedia Commons, uploaded by Chaosprime, 1998 (used under CC BY 3.0)

The first MUD (now known as MUD1) was created by programers Roy Trubshaw and Richard Bartle in 1978. Later MUDs, such as James Aspnes’ Tiny MUD (1989), allowed for more player agency outside of solving puzzles and allowed players to create objects and landscapes. Aarseth writes that,

As literature (although not as textual media), MUDs are very different from anything else, with their streams of continuing text and their collective, often anonymous readership and writership. Life in the MUD is literary, relying on purely textual strategies, and it therefore provides a unique laboratory for the study of textual self-expression and self-creation, themes that are far from marginal in the practice of literary theory. (1997)

We can see player autonomy in constructing narratives play a huge role in today’s gaming world. Games such as Life is Strange (2015) or the Telltale Games (2005–present) series offer the player the ability to choose from a selection of dialogue or actions. These decisions determine which branch of the story the player accesses and ultimately, the outcome of the game, with players experiencing a range of limited endings. The ergodic nature of video games derives from the amount of player autonomy:

In video games, most of which are ergodic texts, a player must make active choices with unknown consequences in order to cocreate his experience [...] The game remains ergodic (if, in some instances, barely), not something one can passively follow, turning the pages, letting the words flow by. To play a game is to be active, engaged, participating. (Melissa Kagen, “Walking Simulators, #Gamergate, and the Gender of Wandering,” in The Year's Work in Nerds, Wonks, and Neocons, 2017).

Edited by Jonathan P. Eburne and Benjamin Schreier

In video games, most of which are ergodic texts, a player must make active choices with unknown consequences in order to cocreate his experience [...] The game remains ergodic (if, in some instances, barely), not something one can passively follow, turning the pages, letting the words flow by. To play a game is to be active, engaged, participating. (Melissa Kagen, “Walking Simulators, #Gamergate, and the Gender of Wandering,” in The Year's Work in Nerds, Wonks, and Neocons, 2017).

Criticisms of Aarseth’s theory

One of the main criticisms of Aarseth’s theory of ergodic literature, and his method of categorising cybertexts, is that he does not make enough of a distinction between the medium of the text and its content. N. Katherine Hayles writes that Aarseth’s method “is blind to content and relatively indifferent to the specificity of media (“Electronic Literature: What is it?” in Doing Digital Humanities, 2016)

However, Aarseth does make it clear that he is focused on theory and the structure of the text, rather than its content; this is not an oversight but an intentional methodological decision.

Hayles further criticism of Aarseth’s theory, though she does acknowledge his significance in furthering the field of electronic textuality, is that

it is almost powerless to illuminate the possibilities of an individual text, beyond indicating the functions a text employs. It cannot tell us, for example, why or in what sense Michael Joyce's Afternoon, a story (Eastgate Systems, 1990) succeeds as a narrative fiction, or why one text may be more compelling or memorable to users than another. (“What Cybertext Theory Can’t Do,” Electronic Book Review, 2001)

The lack of acknowledgement of the emotions or interests of the user has been remarked upon by other scholars. As Frank Furtwängler points out in “Human Practice,” that is is “rather sad” that Aarseth does not focus “on the desires of the user”:

To do that would have fulfilled two tasks: first, a relativization of the radical emphasis of the materiality of the medium as given in his approach; and second, a real revision or radicalization of reader-response theory, which was in fact a veiled theory of production. (in The Aesthetics of Net Literature, 2015)

Edited by Peter Gendolla and Jörgen Schäfer

To do that would have fulfilled two tasks: first, a relativization of the radical emphasis of the materiality of the medium as given in his approach; and second, a real revision or radicalization of reader-response theory, which was in fact a veiled theory of production. (in The Aesthetics of Net Literature, 2015)

However, what seems to unite these scholars is their acknowledgement of the significant contributions made by Aarseth. Critics such as Markku Eskelinen (“Six Problems in Search of a Solution,” in The Aesthetics of Net Literature, 2015) and Marie-Laure Ryan (Avatars of Story, 2006) have engaged with Aarseth’s work, with Ryan referring to it as “groundbreaking” (2006). Clearly, Aarseth’s work on ergodic literature has been instrumental in game, media, digital humanities, and literary studies, through its challenge of traditional narratology and recognition of reader agency.

Interactive media and the future of the ergodic

In Identity and Play in Interactive Digital Media, Sara M. Cole highlights how ergodic forms will continue to shape our culture and society:

Interactive media will increasingly become the vehicle for our cultural narratives, shaping our sense of self and society as other media have done before them. The specific affordances of this new interactive form alter our modes of personal development. (2017)

Sara M. Cole

Interactive media will increasingly become the vehicle for our cultural narratives, shaping our sense of self and society as other media have done before them. The specific affordances of this new interactive form alter our modes of personal development. (2017)

We can see how readers are being afforded more choices with emerging technologies and can participate in story creation.

We can see ergodic literature enter the mainstream with platforms such as Netflix producing interactive films and television series, such as Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (2018) and Choose Love (2023), in which the viewer must make decisions on behalf of the protagonist, taking on the dual role of director and viewer.

The emergence of AI systems, such as ChatGPT, has also created new opportunities for readers to co-produce the texts they read. ChatGPT can produce stories, poems or song lyrics, providing a prompt is entered by the user. This need for a prompt (an idea to base the text on) requires non-trivial effort. The user can also keep adding information to refine the story.

The popularity of RPGs, video games, and other forms of interactive narratives demonstrates how traditional reading methods are challenged, as the way we consume literature is evolving. In our digital age, focused heavily on content creation, we can see a move away from passive consumption and towards fostering a participatory culture in the way we engage with texts.

Further reading on Perlego

Towards a Digital Poetics: Electronic Literature & Literary Games (2019) by James O’Sullivan

Narrative Factuality: A Handbook (2019) Edited by Monika Fludernik and Marie-Laure Ryan

Ludotopia: Spaces, Places and Territories in Computer Games (2019) Edited by Espen Aarseth and Stephan Günzel

Ergodic literature FAQs

What is ergodic literature in simple terms?

What is ergodic literature in simple terms?

What are some key characteristics of ergodic literature?

What are some key characteristics of ergodic literature?

What is a cybertext?

What is a cybertext?

What is hypertext?

What is hypertext?

What is an example of ergodic literature?

What is an example of ergodic literature?

Bibliography

Aarseth, E. J. (1997) Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. John Hopkins University Press.

Apollinaire, G. (2004) Calligrammes: Poemes de la paix de la guerre. University of California Press.

Armitage, G. Claypool, M., and Branch, P. (2006) Networking and Online Games: Understanding and Engineering Multiplayer Internet Games. Wiley. Available at:

Bohn, W. (2018) Reading Apollinaire's Calligrammes. Bloomsbury Academic. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/801120/reading-apollinaires-calligrammes

Cole, S. M. (2017) Identity and Play in Interactive Digital Media: Ergodic Ontogeny. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1486927/identity-and-play-in-interactive-digital-media-ergodic-ontogeny

Coover, R. (1992) “The End of Books” New York Times

Cortazar, J. (1963) Hopscotch. Goatshed Press.

Cummings, E. E. (2019) Tulips & Chimneys. Dover Publications. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/970742/tulips-chimneys

Danielewski, M. Z. (2000) House of Leaves. Penguin Random House.

Eskelinen, M. (2015) “Six Problems in Search of a Solution,” in Gendolla, P., and Schäfer, J. (eds.) The Aesthetics of Net Literature. Available at:

Hayles, N. K. (2001) “What Cybertext Theory Can’t Do,” Electronic Book Review.

Hayles, N. K. (2016) “Electronic Literature: What is it?” in Crompton, C., Lane, R. J., and Siemens, R. (eds.) Doing Digital Humanities: Practice, Training, Research. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2192829/doing-digital-humanities-practice-training-research

Heise-von der Lippe, A. (2021) Monstrous Textualities: Writing the Other in Gothic Narratives of Resistance. University of Wales Press. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/2801028/monstrous-textualities-writing-the-other-in-gothic-narratives-of-resistance

The I Ching or Book of Changes. (2011) Translated into English by Cary F. Baynes. https://www.perlego.com/book/1114821/the-i-ching-or-book-of-changes

Kagen, M. (2017) “Walking Simulators, #Gamergate, and the Gender of Wandering,” in Eburne, J. P., and Schreier, B (eds.) The Year's Work in Nerds, Wonks, and Neocons. Indiana University Press. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/569200/the-years-work-in-nerds-wonks-and-neocons

Facundo, A. C. (2016) Oscillations of Literary Theory. SUNY Press. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/2672096/oscillations-of-literary-theory-the-paranoid-imperative-and-queer-reparative

Furtwängler, F. (2015) “Human Practice: How the Problem of Ergodicity Demands a Reactivation of Anthropological Perspectives in Game Studies,” in Gendolla, P., and Schäfer, J. (eds.) The Aesthetics of Net Literature. Available at:

Nelson, T. (1988) Literary Machines. Mindful Press.

Ryan, M. L. (2006) Avatars of Story. University of Minnesota Press.

Rettberg, S. (2018) Electronic Literature. Polity. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/1536490/electronic-literature

Shelley, M. (2013) Frankenstein. Dover Publications. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/113049/frankenstein

Schober, R. (2023) Spider Web, Labyrinth, Tightrope Walk: Networks in US American Literature and Culture. De Gruyter. Available at:

Wolf, M. J. P., and Perron, B. (eds.) (2013) The Video Game Theory Reader. Routledge. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/1613010/the-video-game-theory-reader

Illustrations and images

Guillaume Apollinaire (1914) “Lettre-Océan” Wikimedia Commons, 2013. Available at:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guillaume_Apollinaire_-_Calligramme_-_Lettre-oc%C3%A9an.png

“Eight Trigrams” from Cary F. Baynes and Richard Wilhem’s translation of The I Ching, or Book of Changes, 2011.

Lost Souls screenshot - River Tethys combat,” Wikimedia Commons, uploaded by Chaosprime, 1998; CC 3.0.

Digital media

Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (2018) Directed by David Slade and written by Charlie Brooker. Netflix.

Choose Love (2023) Directed by Stuart McDonald. Netflix

Jackson, S. (1995) Patchwork Girl. Eastgate.

Joyce, M. (1987–90) “afternoon, a story”. Norton Anthology of Postmodern American Fiction special web edition.

Life is Strange (2015) Developed by Don’t Nod. PlayStation, Xbox, and Windows.

MUD1 (1978) Created by Roy Trubshaw and Richard Bartle

Telltale Games (2005–present) Telltale Incorporated.

PhD, English Literature (Lancaster University)

Sophie Raine has a PhD from Lancaster University. Her work focuses on penny dreadfuls and urban spaces. Her previous publications have been featured in VPFA (2019; 2022) and the Palgrave Handbook for Steam Age Gothic (2021) and her co-edited collection Penny Dreadfuls and the Gothic was released in 2023 with University of Wales Press.