What is Avant-Garde?

PhD, Media Arts (Royal Holloway, University of London)

Date Published: 06.03.2023,

Last Updated: 19.07.2024

Share this article

What is the meaning of Avant-Garde?

The term ‘avant-garde’ comes from the French ‘advance guard’, referring to a group of soldiers that leads an army into battle. This metaphor aptly suggests that the artists of the avant-garde movement were pioneers, forging a fresh cultural path. Indeed, avant-garde artists sought to challenge the way society saw things — the way that beauty and values were conceived and measured — all through the development of new, strange, and often abstract artworks. Denoting cultural changes in philosophy, art, literature, fashion, film, performance and music, the avant-garde was a historical moment that saw boundaries pushed and the status quo challenged.

Avant-garde art was a prominent feature during the rise of modernism, widely accepted to span the early decades of the 20th century. The avant-garde was a cultural response to modernity, an era characterized by a post-industrial, capitalist society that saw the rise of globalization, technology and mass production, accompanied by a sense of societal progress. Avant-garde art challenged this metaphysical certainty — this belief in an ever-approaching utopia — instead exhibiting a political and intellectual radicalism.

John Roberts claims in Revolutionary Time and the Avant-Garde that the avant-garde represents,

an unyielding source of artistic re-adaptation and re-theorization...this is because the avant-garde in its revolutionary forms produced a profound shift in expectations about art that coincided with the demise of traditional bourgeois cultural relations and practices and bourgeois modes of aesthetic judgement. (2015)

John Roberts

an unyielding source of artistic re-adaptation and re-theorization...this is because the avant-garde in its revolutionary forms produced a profound shift in expectations about art that coincided with the demise of traditional bourgeois cultural relations and practices and bourgeois modes of aesthetic judgement. (2015)

Avant-garde art was generally skeptical of modernity's atmosphere of progress and opposed to the cultural standards of elite institutions and the upper classes.

Hilton Kramer explores the complexity of this artistic development in The Age of the Avant-Garde. He writes, ‘at one extreme, there is indeed an intransigent radicalism that categorically refuses to acknowledge the contingent and rather fragile character of the cultural enterprise, a radicalism that cancels all debts to the past in the pursuit of a new vision, however limited and fragmentary and circumscribed, and thus feels at liberty — in fact, compelled — to sweep anything and everything in the path of its own immediate goals, whatever the consequences’ (2017).

Some avant-garde art movements saw this ‘new vision’ as a subversion of rational thought, while others hoped for a radical acceptance of the machine age, but what united the avant-garde was the way these artists challenged the status quo and sought to reestablish the role of art in society.

What Kramer most significantly touches on is the challenge that the avant-garde poses in the designation of an overarching definition. The tendency has been to confine it to a particular character, time and place; a radical euro-centric cultural category and historical epoch. This approach has garnered criticism that the avant-garde, conceived in this narrow way, diminishes its contemporary or international relevance and its diverse and tense set of ideals. With this in mind, however, in order to reappraise the meaning and significance of avant-garde art, we must first understand what it originally and most generally refers to: the development of western art in the 20th century.

The historical versus the neo-avant-garde

While avant-garde art is recognized as belonging to the initial rise of modernism, its principles and practices can also be observed in the latter half of the 20th century. In the crucial 1984 text, Theory of the Avant-Garde, Peter Bürger designates the modernist avant-garde as ‘historical’ and the avant-garde of the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, as ‘neo’.

Bürger traces the context of the historical avant-garde, noting that it was preceded by an adherence to aestheticism. Before the avant-garde, art was representational and naturalist; either a religious tool or merely art for art’s sake. The avant-garde defied this purpose and function of art, rebelling against the oppression of the bourgeoisie and the tastes of the middle classes. The bourgeoisie, based on the long-standing aesthetics of western religion, saw art as a means of upholding cultural power while the middle classes were only interested in art as a form of entertainment. This was the society against which the avant-garde artist rebelled; hence the historical avant-garde became understood as a development jettisoned from its preceding history and from society at large.

The neo-avant-garde, according to Bürger, had its own set of challenges. Bürger outlines one such challenge: ‘since now the protest of the historical avant-garde against art as institution is accepted as art, the gesture of protest of the neo-avant-garde becomes inauthentic’ (1984, 53). How could the neo-avant-garde embody the same new, revolutionary approach as the historical avant-garde, only decades later? Bürger suggests that, if the historical avant-gardists were successful in any way, it was only because they did it first. While the neo-avant-garde’s purpose could align with that of the historical avant-garde, Bürger asserts that ‘the neo-avant-garde institutionalizes the avant-garde as art and thus negates genuinely avant-gardiste intention’ (1984).

Elsewhere, however, the tension Bürger outlines between the historical avant-garde and the neo-avant-garde is complicated. Roberts contends that ‘in America in the early 1960s, the generation of artists who produced that extraordinarily long sequence of neo-avant-garde achievement… had little or no knowledge of the historic avant-garde, and had to recover it as a living history in order to define their distance from painterly modernism’ (2015). This suggests that the neo-avant-garde was not a pale imitation of the historical, but rather responsive to its own set of societal conditions.

Whether Bürger’s evaluations of the historical and the neo-avant-gardes seem, at times, reductive and unduly harsh, the expanse of insight into the intention and effect of avant-garde art that Theory of the Avant-Garde offers has positioned it as a crucial text in the study of modernism. The avant-garde categories that Bürger established allow scholars to trace the development of the avant-garde and attend to some of its defining features and paradoxes.

Avant-garde movements and works

The term ‘avant-garde art’ has not only come to describe a type of art developed in the early 20th century but also become an umbrella term for the various artistic movements that exhibited the revolutionary avant-garde principle. These pioneering artistic activities each contributed something unique to the avant-garde ethos. Avant-garde art movements typically move along a spectrum between pure abstraction and strange or irrational renderings of the world, together engendering a new role of art in society and a new way of seeing the world. Although it is Bürger’s assertion that it was ‘a distinguished feature of the historical avant-garde movements that they did not develop a style’ — that ‘there is no such thing as a Dadaist or a surrealist style’, for example — these movements nonetheless can be explored and categorized through the set of principles that guided their vanguard and the aesthetic that these principles produced (1984, 18).

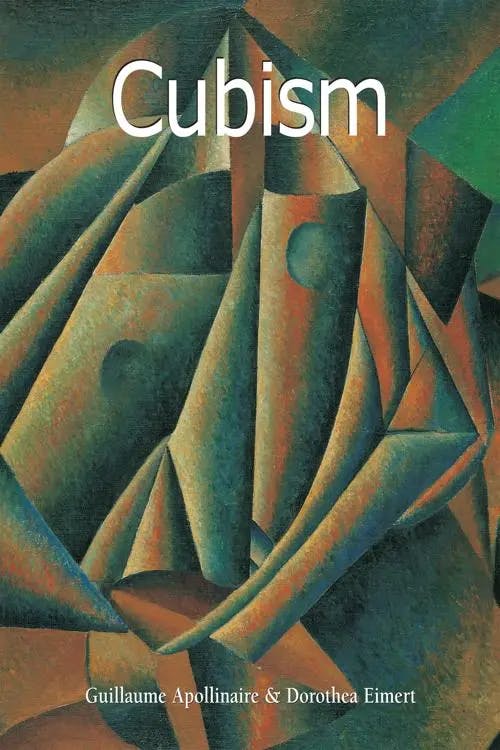

Cubism was avant-garde art movement that played with perspective, fragmenting the world and forcing the viewer to piece together this newly rendered relationship between space and time into a comprehensible image. Cubism augmented reality by expanding how much the eye was capable of observing at once.

As Guillaume Apollinaire and Dorothea Eimert describe in Cubism, the Cubists,

no longer painted an object viewed from one perspective, but rather layered views from many angles in order to capture the subject from all sides. They analysed the object and brought it to the canvas as a fragmented picture. Shape and space melted into one another in one composition of enmeshed, intersected and dissected surfaces. (2014)

Guillaume Apollinaire, Dorothea Eimert

no longer painted an object viewed from one perspective, but rather layered views from many angles in order to capture the subject from all sides. They analysed the object and brought it to the canvas as a fragmented picture. Shape and space melted into one another in one composition of enmeshed, intersected and dissected surfaces. (2014)

Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) is often referred to as the ‘first Cubist picture’ (Barr, 2019). The painting depicts five women whose strangely angular bodies and disjointed positions in the space exhibit an abandonment of naturalist perspective. Their faces are reminiscent of traditional African masks, indicating the important presence of tribal and indigenous art in avant-garde works. Les Demoiselles d'Avignon’s lasting impression is one that saw the classical nude motif grotesquely fractured and fragmented, and the cultural standards of European aesthetic beauty expanded to include visions of what, at that time, was perceived to be ‘primitive’ and unrefined.

Dada was another crucial movement of the historical avant-garde. Bürger identified in Dada the absolute rejection of the art establishment, provoking him to label it ‘the most radical movement within the European avant-garde’ (22). One of Dada’s most important contributions to the avant-garde was Marcel Duchamp’s ‘readymades’. In Duchamp, Juan Ramírez explains that, in a readymade, ‘the artist does not create, in the traditional sense of the word, but chooses from among the objects of the industrial world or (to a lesser degree) the world of nature’ (2013). Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) is a readymade that has become emblematic of avant-garde art. Fountain is a urinal, signed ‘R. Mutt’, positioned on its back, and placed in a gallery setting. The presence of a mass-produced and mundane, even vulgar, object in a formal art institution blurred the lines between high art and the everyday and begged the question ‘what makes something art?’

Abstract Expressionism was a neo-avant-garde movement developed in New York that used bold techniques to create works of art that prioritised introspection and emotion over world-representation. The emotional outburst detectible in Abstract Expressionist works is widely understood as an exhibition of post-war grief and anxiety. Abstract Expressionism was the movement that saw the rise of Jackson Pollock to prominence, whose splattered canvases exhibited a violent attack on the act of painting itself. With his famous ‘drip style’ where he flung and splattered paint across a huge canvas, Pollock used elements of coincidence and the unconscious most often associated with Surrealism; he was concerned with what Claude Cernuschi calls the ‘compatibility of meaning and abstraction’ (2021). Pollock’s 1950 work, One: Number 31, is an example of a piece of Abstract Expressionism which captures the sense of the dynamism and energy that went into its creation. One: Number 31, like so many of his works, exhibits a collaboration between Pollock’s movement and the forces of gravity and coincidence, provoking questions of the relationship between the artist and their work, and the intentionality of creativity.

Summarising the Avant-Garde

This guide offers only a small sample of avant-garde art movements and their offerings. Other significant movements include Expressionism, Surrealism, Futurism, Constructivism, Fluxus and Pop Art. ‘Each of these’, asserts Willard Bohn in The Early Avant-Garde in Twentieth-Century Literature and Art,

arose in response to recent scientific, technological, and/or philosophical developments that drastically affected modern civilization. In turn, each was responsible for a major paradigm shift that altered the way in which we view—and respond to—the world around us (2018)

Willard Bohn

arose in response to recent scientific, technological, and/or philosophical developments that drastically affected modern civilization. In turn, each was responsible for a major paradigm shift that altered the way in which we view—and respond to—the world around us (2018)

These art movements, in combination with the developments in fashion, literature, music, theatre and film, all contributed to the revolutionary, satirical, absurd and confrontational character of the avant-garde.

Recent developments in modernist studies have sought to expand this definition of avant-garde art. The term is being reappraised to involve art from across the world, including the way that the avant-garde intersects with folk art and indigenous cultures in a wider effort to decolonize the world of art history. Furthermore, contemporary works that transgress the expectations of the art world and challenge the relationship between art and society may bear the label of avant-garde, proving it to be not only a historical moment but a relevant and alive artistic concept.

Further Avant-Garde Reading & Resources on Perlego:

Visions of Avant-Garde Film by Kamila Kuc

The Sixth Sense of the Avant-Garde by Irina Sirotkina and Roger Smith

In Search of a Lost Avant-Garde by Matti Bunzl

Art, Mimesis and the Avant-Garde by Andrew Benjamin

Bibliography

Apollinaire, Guillaume, and Dorothea Eimert. Cubism. Parkstone International, 2014.

Barr, Alfred. Cubism and Abstract Art. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2019.

Bohn, Willard. The Early Avant-Garde in Twentieth-Century Literature and Art. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2018.

Bürger, Peter. Theory of the Avant-Garde. Manchester UP, 1984.

Cernuschi, Claude. Jackson Pollock. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2021.

Kramer, Hilton. The Age of the Avant-Garde. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2017.

Ramírez, Juan. Duchamp. Reaktion Books, 2013.

Roberts, John. Revolutionary Time and the Avant-Garde. Verso, 2015.

PhD, Media Arts (Royal Holloway, University of London)

Aoiffe Walsh has a PhD in Media Arts from Royal Holloway, University of London. With a background in film studies and philosophy, her current research explores British literary modernism, with a particular focus on surrealism between the wars. She has lectured and published pieces on documentary and film theory, film history, genre studies and the avant-garde.