What is Psychogeography?

PhD, English Literature (Lancaster University)

Date Published: 02.08.2023,

Last Updated: 05.08.2024

Share this article

Defining psychogeography

For some, the city is a bustling, stimulating space, brimming with opportunities for connection and exploration. Others, however, may experience that same metropolis as a claustrophobic and frustrating concrete jungle. How a person feels about a specific place, or type of place, is due to a wide array of factors; these preferences may be due to the architecture, layout, or our personal associations with that place. Our personal experience of a space may also be impacted by factors such as neurodiversity; the cacophony of sounds in the city may cause sensory overload for those with sensory processing issues. A way to understand the variance in our reactions to a space is through psychogeography.

In his much-cited essay “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography” (1955), Guy Debord defines “psychogeography” as

the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals. (Debord, in The Situationists and the City, 2020)

Edited by Tom McDonough

the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals. (Debord, in The Situationists and the City, 2020)

Debord was fascinated by the reactions that different individuals had to the same spaces and how a single space could provoke a multitude of different responses. He writes,

[...] the variety of possible combinations of environments, analogous to the dissolution of pure chemical bodies in an infinite number of mixtures, entails feelings as differentiated and as complex as those provoked by any other form of theater. And the slightest clear-headed search makes evident that no distinction, whether qualitative or quantitative, between the influences of diverse settings built in a city can be inferred from an architectural era or style, much less from housing conditions. (Debord, 1955, [2020])

In other words, we cannot attribute our feelings towards a space solely due to its aesthetic features. Instead, we must look at the multitude of “combinations” within an environment, such as:

- Design and layout

- Personal associations and memories

- The type of activity that occurs in that place

- Sensory factors (i.e., particular smells or sounds)

In order to fully study how the environment impacts the behavior and emotions of individuals, psychogeographers must walk through the city, taking notes of the emotions, behaviors, and thoughts that arise. These notations would be used for a variety of purposes both scholarly and creative. The observations made by psychogeographers have contributed to academic discourse on urban spaces and planning, and have resulted in creative works such as Debord’s reimagined Parisian maps and, more recently, the writings of Iain Sinclair and Will Self, among others.

Guy Debord & psychogeography’s beginnings

Psychogeography was one of the key contributions of the Paris-based avante-garde group, The Letterist International (1952-57). This collective would eventually transform into the radical group The Situationist International (1957–72). The Letterist International, founded by Debord and artist Gil J. Wolman, promoted art as a way of disrupting or subverting capitalist ideologies (such as using slogans to make anti-capitalist art).

The term “psychogeography” itself is credited to the “illiterate” group member, Kabyle (Debord, 1955, [2020]). The first discussion of the term appeared in the Potlatch (a Letterist journal) in 1954. Here, the reader is encouraged to partake in their “Psychogeographical Game of the Week”:

Depending on what you are after, choose a region, a more or less densely populated city, a more or less lively street. Build a house. Furnish it. Make the most of its decoration and its surroundings. Choose the season and the time. Gather together the most fitting people, with suitable records and drinks. Lighting and conversation must, of course, be appropriate, along with the weather or your memories. If there has been no error in your calculations, you should find the outcome satisfying. (Cited in Debord, 1955, [2020])

The concept of psychogeography was further developed by Ivan Chtcheglov (pseudonym Gilles Ivain) in his essay “Formulary for a New Urbanism” (1958), available in The Situationists and the City (2020). Chtcheglov writes,

All cities are geological and three steps cannot be taken without encountering ghosts, bearing all the prestige of their legends. We maneuver within a closed landscape whose landmarks constantly draw us toward the past. Certain shifting angles, certain receding perspectives allow us to glimpse original conceptions of space, but this vision remains fragmentary. It must be sought in the magical locales of folkloric tales and surrealist writings: castles, endless walls, little forgotten bars, Mammoth Cave, mirrors of Casinos.

Chtcheglov makes explicit the connection between the objective reality and history of a space and our experience of it; this experience informed literature, legendary tales and our ever-changing knowledge of the landscape and the culture.

Though Chtcheglov’s article was highly influential, it is not until Debord’s writing that psychogeography gains real traction. In 1957, the members of The Letterist International, along with new members, created The Situationist International (SI). The SI was predominantly concerned with how capitalism had resulted in the gentrification of urban spaces. As Alex J. Bridger writes,

Their aims, tactics and strategies were to work towards the downfall of capitalist society. They believed that radical theory and practice could not exist in universities and other such academic contexts as any radical potential of knowledge would eventually be recuperated by those in power and the bourgeois institutions in which such academics worked. The intellectual terrain for the situationists was that of the streets and bars of Paris and London. (2022)

Alex J. Bridger

Their aims, tactics and strategies were to work towards the downfall of capitalist society. They believed that radical theory and practice could not exist in universities and other such academic contexts as any radical potential of knowledge would eventually be recuperated by those in power and the bourgeois institutions in which such academics worked. The intellectual terrain for the situationists was that of the streets and bars of Paris and London. (2022)

The art of observation: flânerie and dérive

One of the most central aspects of Debord’s psychogeography is the concept of dérive (translated as “to drift”), a method of observation for psychogeographers. Before we explore dérive further, it is important to acknowledge a similar practice that originated in the nineteenth century in France: flânerie.

Flânerie was a type of urban wandering practiced by men of leisure, known as flâneurs. The French term “flâneur” translates roughly as “stroller” or “loafer”, and describes a man who would wander the streets, without clear direction or purpose in order to explore new spaces and observe passers-by. The figure of the flâneur is most often associated with the French poet Charles Baudelaire (1821-67), whose essay “The Painter of Modern Life” (1863),

[...] cemented the flâneur’s recognition among international audiences, including English authors and readers. His essay helped popularize the figure’s definition as an urban man who aimlessly wanders the city streets in search of visual stimulation. (S. Brooke Cameron, 2020)

S. Brooke Cameron

[...] cemented the flâneur’s recognition among international audiences, including English authors and readers. His essay helped popularize the figure’s definition as an urban man who aimlessly wanders the city streets in search of visual stimulation. (S. Brooke Cameron, 2020)

Marit Grøtta points out the complexities and contradictions within this urban persona that cause it to resist definition or clear categorization. She writes,

The flâneur represents the urban experience with all its aspects: he is an urban stroller, a street-artist, an accidental gaze, an amateur detective. With his heightened sensibility, the flâneur became an index of the dramatic changes that occurred as the city of Paris was transformed into a modern metropolis. (2015)

Marit Grøtta

The flâneur represents the urban experience with all its aspects: he is an urban stroller, a street-artist, an accidental gaze, an amateur detective. With his heightened sensibility, the flâneur became an index of the dramatic changes that occurred as the city of Paris was transformed into a modern metropolis. (2015)

It is clear to see why psychogeography is bound up with the romantic concept of flânerie. However, unlike the passiveness of flânerie, psychogeographers walk with purpose, with some seeing the act of walking as politically charged (which I go on to explore later in this guide).

Rather than reviving flânerie, Debord proposed the psychogeographer must conduct a dérive. He famously wrote of this practice in his essay “Theory of the dérive” (1958). Here, he explains the process:

In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their usual motives for movement and action, their relations, their work and leisure activities, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there. The element of chance is less determinant than one might think: from the dérive point of view cities have a psychogeographical relief, with constant currents, fixed points and vortexes which strongly discourage entry into or exit from certain zones. (Debord, in The People, Place, and Space Reader, 2014)

Edited by Jen Jack Gieseking et al.

In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their usual motives for movement and action, their relations, their work and leisure activities, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there. The element of chance is less determinant than one might think: from the dérive point of view cities have a psychogeographical relief, with constant currents, fixed points and vortexes which strongly discourage entry into or exit from certain zones. (Debord, in The People, Place, and Space Reader, 2014)

Put simply, a dérive is an unplanned stroll with no route or destination in mind; the walker allows themselves to be guided by instinct. However, as Debord points out, this is not a random act as urban space is designed, with all of its contours, road markings, and barriers, to encourage pedestrians to walk a certain route. Markers in the city that delineate where we can and cannot trespass are not always as overt as a no-entry sign; we may, for example, be dissuaded by a route that does not have a clear footpath or streetlamps. A dérive invites us to explore the city the way it was designed to be explored, whilst also encouraging us to question these urban planning choices.

Debord further sets out some key points or guidelines for conducting a dérive and what one can expect from such a pastime.

- It is best to dérive in industrial cities.

- It is often better to work in groups of people who have the same level of awareness, than to dérive alone.

- The dérive may change course or direction and the group may subdivide and follow different pursuits.

- The average duration is one day, though Debord does highlight how one such excursion was reported to have lasted a month.

- The very late hours of the night are unsuitable for dérives.

- Prolonged rain may prevent dérives, but storms and other forms of precipitation are usually acceptable.

- The location chosen for a dérives is quite broad in scope and these can be specific, named sites, or vague areas “depending on whether the goal is to study a terrain or to emotionally disorient oneself.”

(Debord, 1958, [2014])

Debord acknowledges that chance plays an essential role in dérives at this stage as “the methodology of psycho-geographical observation is still in its infancy.” Regardless, he remains hopeful:

Progress means breaking through fields where chance holds sway by creating new conditions more favorable to our purposes. We can say, then, that the randomness of a dérive is fundamentally different from that of the stroll, but also that the first psychogeographical attractions discovered by dérivers may tend to fixate them around new habitual axes, to which they will constantly be drawn back. (Debord, 1958, [2014])

Early dérivers, Debord suggests, play a vital role in the field by uncovering new sites of interest from which more detailed study can take place.

Gothic geographies

It is important to note the significance of nineteenth-century Gothic literature on the formation of psychogeography as a field of intrigue. During this period, Gothic fiction seized upon their readers’ fears of urban crime, highlighting how the layout of the city made it possible for degenerate criminals to hide in plain sight. Urban mysteries in particular became a popular form of fiction in both England and France: one of the most popular of the genre being George. W.M. Reynolds’s penny dreadful The Mysteries of London (1844-46), inspired by Eugene Sue’s The Mysteries of Paris (1842-43). The terrifying allure of the labyrinthine city continued with writers such as Robert Louis Stevenson in the period known as the “fin de siècle”, or “end of the century.” (For more information, see our study guide “What was the Fin de Siècle?”)

The thrills of these more “dangerous” excursions via literature spilled into the real lives of the readers, many of whom began to partake in activities such as “slumming” (Seth Kovan, Slumming, 2006). This refers to the practice of visiting slums as an observer. Though these acts of voyeuristically gaining access to prohibited urban spaces do not have quite the same goals or methods as Debord proposes, it is important to note their significance in contributing to a culture of observation as a pastime.

The Gothic connotations of urban exploration continue in psychogeography today. As Merlin Coverly writes,

[...] crime and lowlife in general remain a hallmark of psychogeographical investigation and the revival of psychogeography in recent years has been supported by a similar resurgence of gothic forms. (2018)

Merlin Coverley

[...] crime and lowlife in general remain a hallmark of psychogeographical investigation and the revival of psychogeography in recent years has been supported by a similar resurgence of gothic forms. (2018)

Coverly points out that contemporary psychogeographers Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd have a “tendency to dramatise the city as a place of dark imaginings”. T, and their “obsession with the occult” and the past means that “contemporary psychogeography as closely resembles a form of local history as it does a geographical exploration.” (2018)” We can see this in Peter Ackroyd’s Colours of London (2022) where he writes, in true Gothic fashion,

Blackness is of the city’s essence. It partakes of its true identity; in a literal sense London is possessed by blackness in the form of grease, muck, filth, mud, gloom and night.

Peter Ackroyd

Blackness is of the city’s essence. It partakes of its true identity; in a literal sense London is possessed by blackness in the form of grease, muck, filth, mud, gloom and night.

Walking as a radical act

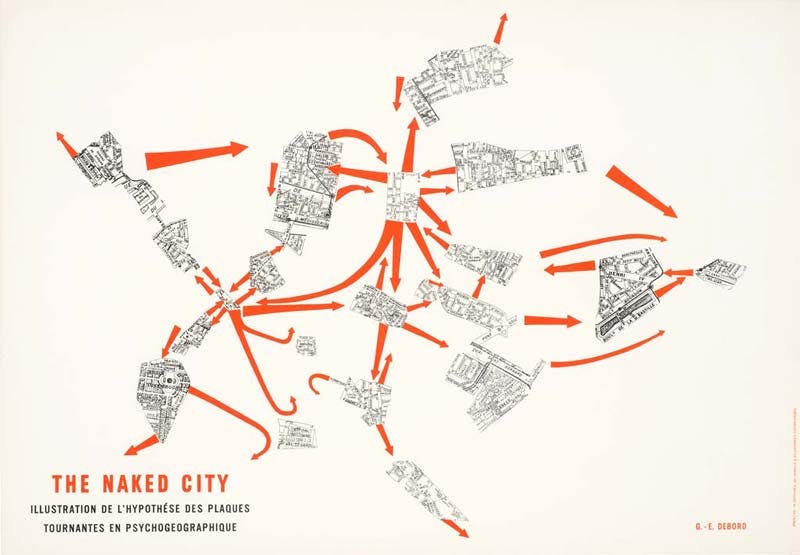

Psychogeography often involves a politically charged re-mapping of the city. The psychogeographic maps produced by Debord in the 1950s are a perfect example of the radical potential of this field. “The Guide Psychogéographique de Paris” and “The Naked City” (Figure 1, 1957) subverted expectations of what we would expect to see on a map of Paris, challenging our notions of authority and truth.

Figure 1. Guy Debord (1957) "The Naked Map" (CC BY 4.0)

In Cartographic Strategies of Postmodernity (2013), Peta Mitchell writes,

Each map “détournes” or “diverts” a preexisting utilitarian Parisian map such as one might find in an A-Z guide. The earlier of Debord’s maps, the Guide Psychogéographique, is made up of fragments of the 1956 Blondel la Rougery Plan de Paris à vol d’oiseau. Dissected and rearranged, the original map’s bird’s eye view is distorted: the Seine is removed, and while some quartiers appear mutilated and rotated out of their usual alignment many others have simply been excised, replaced with arrows linking the remaining fragments.

Peta Mitchell

Each map “détournes” or “diverts” a preexisting utilitarian Parisian map such as one might find in an A-Z guide. The earlier of Debord’s maps, the Guide Psychogéographique, is made up of fragments of the 1956 Blondel la Rougery Plan de Paris à vol d’oiseau. Dissected and rearranged, the original map’s bird’s eye view is distorted: the Seine is removed, and while some quartiers appear mutilated and rotated out of their usual alignment many others have simply been excised, replaced with arrows linking the remaining fragments.

Debord and the Letterists recognized the political and cultural power of the map in determining landmarks and allowing other spaces to fall into obscurity. As we use maps as sources of objective truth and reality, Debord’s remapping of Paris highlights how these forms of knowledge are constructed with particular agendas in mind.

Contemporary psychogeographers have taken inspiration from Debord and explored the myriad of ways that urban spaces and the act of walking are politicized, and how pedestrians can resist controls placed on them by urban planning. Coverly writes,

This act of walking is principally an urban affair, and in cities that are often hostile to the pedestrian, it inevitably becomes an act of subversion. Walking has long been seen as contrary to the spirit of the modern city. The promotion of swift circulation and the street-level gaze that walking requires allows one to challenge the official representation of the city by cutting across established routes and exploring those marginal and forgotten areas often overlooked by the city’s inhabitants. In this way, the act of walking becomes bound up with psychogeography’s characteristic opposition to political authority. (2018)

This “official representation” is mandated for the pedestrian through designated routes and barriers intended to seal off entire areas to the public. We also see that, as cities modernize and businesses buy up vacant land, areas that were once accessible are now prohibited.

In “The flâneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore: The Politics of Loitering”, Susan Buck-Morss writes,

Today, it is clear to any pedestrian in Paris that, within public space, automobiles are the dominant and predatory species. They penetrate the city’s aura so routinely that it disintegrates faster than it can coalesce. (Buck-Morss, in Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project, 2006)

Edited by Beatrice Hanssen

Today, it is clear to any pedestrian in Paris that, within public space, automobiles are the dominant and predatory species. They penetrate the city’s aura so routinely that it disintegrates faster than it can coalesce. (Buck-Morss, in Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project, 2006)

All of this dissuades individuals from exploring their city and straying from familiar paths, further contributing to a homogenized, tightly controlled rendering of the city.

Notable psychogeographer Iain Sinclair has produced numerous works on his experience of the city and his exploration of it is often seen as a form of protest against certain forms of development and neoliberal politics. In Living with Buildings (2018), he writes,

I had my own defensive magic in place, the routine of walking unresolved problems out into the city, eavesdropping on random incidents, forcing connections, and carrying annotations and photographs back to the house in which I had lived for fifty years.

Iain Sinclair

I had my own defensive magic in place, the routine of walking unresolved problems out into the city, eavesdropping on random incidents, forcing connections, and carrying annotations and photographs back to the house in which I had lived for fifty years.

Throughout the book, Sinclair details his various journeys and detours, commenting upon the history of the locations he visits and musing upon boundaries between public and private spaces.

Walking as a form of resistance against urbanization can also be seen in the writings of Will Self. Self’s Psychogeography (2007), based on a series of articles written for his column in The Independent, details several journeys including his 25 mile walk to Heathrow Airport. Self highlights how certain developments have made it near impossible for the pedestrian and the city is designed to effectively force people to use public, or private, transport. As Gregory Blair explains in Errant Bodies, Mobility, and Political Resistance (2018),

For Self, walking can be an effective act of insurrection and resistance to the status quo, especially when he takes ten hours to walk to a meeting and is then asked if it took him long to get there.

Gregory Blair

For Self, walking can be an effective act of insurrection and resistance to the status quo, especially when he takes ten hours to walk to a meeting and is then asked if it took him long to get there.

However, unlike Debord and other dérivers, Self does walk with purpose and with destinations in mind.

Psychogeography offers various avenues for resistance to prevailing politics, capitalist expansion, and gentrification. Protest marches, for example, are a way of walking to resist; marches by the group Just Stop Oil, for example, often happen in the middle of roads to create maximum disruption. Within the protest, therefore, there is a second act of resistance: a resistance against how we should experience and walk through the city. While psychogeographers acknowledge that such barriers and boundaries are often there for either convenience or safety, they remark upon how urban planning has changed the city, making it hostile to pedestrians.

Psychogeography today

It is worth acknowledging that psychogeography has developed substantially since its inception. As Merlin Coverly explains,

Debord was fiercely protective of his brainchild and dismissive of attempts to establish psychogeography within the context of earlier explorations of the city. But psychogeography has since resisted its containment within a particular time and place. In escaping the stifling orthodoxy of Debord’s Situationist dogma, it has found both a revival of interest today, as well as retrospective validation in traditions that predate Debord’s conception by several centuries. (2018)

We can see this in how psychogeography has been adapted for the digital age, acknowledging the importance of the time we spend in virtual space. In “Ephemeral cities: Postmodern urbanism and the production of online space,” Mark Nunes identifies that psychogeography’s theory of dérive has important implications for virtual spaces:

Literal ‘spaces of play’ exist throughout the Internet, allowing for encounters that again refuse to entail productive relations or economic exchanges. Likewise, chatrooms, MUDs, MOOs, and IRCs - all forms of real-time online communication - resist productivity and encourage the ludic. (Nunes, in Virtual Globalization, 2020)

Edited by David Holmes

Literal ‘spaces of play’ exist throughout the Internet, allowing for encounters that again refuse to entail productive relations or economic exchanges. Likewise, chatrooms, MUDs, MOOs, and IRCs - all forms of real-time online communication - resist productivity and encourage the ludic. (Nunes, in Virtual Globalization, 2020)

Though this essay was written over twenty years ago, the same holds true today. With the rise of platforms such as TikTok, users can find themselves scrolling for hours a day at content. This is facilitated, and encouraged, by the algorithmically curated “for you” page. Internet users may also regularly find themselves on “deep dives” with each new piece of information taking them further and further from their original search query or interest. Rather than drifting aimlessly influenced by urban planning, we drift aimlessly guided by the algorithm - often a little lost in the internet, and not really knowing how we got there. Perhaps this new form of virtual search and observation has replaced the radical potential of the dérive which Sinclair and Self advocate, replacing it with the passiveness of flânerie.

However, advancements in technology can be used to support and engage with Debord’s original notion of dérive, rather than completely supplanting it. This was particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic when walking became, due to necessity, a national pastime. In 2020, the UK lockdown rules stipulated that residents were only allowed outside for essential work and for a daily walk (either solo or with members of their household).

During this time, The Loiterers Resistance Movement in Manchester, began a series of Sunday walks called “Distance Drifts”; walker Sonia Overall would document her walks, inviting anyone in the area to virtually join her. This had originally begun in 2015 with Overall inviting anyone in the world to join her 15 minutes before sunrise so that they can walk together. In 2020, this moved into a virtual space. Walkers were encouraged to walk with each other at a safe distance, with members of their household bubble, or alone whilst documenting their walk.

As most areas of interest and potential destinations were prohibited, many found themselves wandering aimlessly, taking time to re-acquaint themselves with their local areas. Psychogeography, in this hybridic form, allows walkers respite from the sealed parameters of their home, whilst connecting them to people around the world. These virtual walks allow psychogeography to retain its Debordian roots whilst still making space for our virtual lives.

Further reading on Perlego

Tourism and Retail: The Psychogeography of Liminal Consumption (2012) by Charles McIntyre

The Literary Psychogeography of London: Otherworlds of Alan Moore, Peter Ackroyd, and Iain Sinclair (2020) by Ann Tso

The Last London (2017) by Iain Sinclair

Stroll: Psychogeographic Walking Tours of Toronto (2010) by Shawn Micallef

Psychogeography FAQs

What is psychogeography?

What is psychogeography?

Who coined the term psychogeography?

Who coined the term psychogeography?

Who are some key thinkers in psychogeography?

Who are some key thinkers in psychogeography?

What is a dérive?

What is a dérive?

What is the difference between a flâneur and a dériver?

What is the difference between a flâneur and a dériver?

Bibliography

Ackroyd, P. (2022) Colours of London: A History. Francis Lincoln. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3741947/colours-of-london-a-history-pdf

Bridger, A. J. (2022) Psychogeography and Psychology: In and Beyond the Discipline. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3272051/psychogeography-and-psychology-in-and-beyond-the-discipline-pdf

Blair, G. (2018) Errant Bodies, Mobility, and Political Resistance. Palgrave Pivot. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3494602/errant-bodies-mobility-and-political-resistance-pdf

Buck-Morss, S. (2006) “The flâneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore: The Politics of Loitering” in B. Hanssen (ed) Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. Continuum. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/815290/walter-benjamin-and-the-arcades-project-pdf

Cameron, S. B. (2020) Critical Alliances: Economics and Feminism in English Women's Writing, 1880–1914. University of Toronto Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2328985/critical-alliances-economics-and-feminism-in-english-womens-writing-18801914-pdf

Chtcheglov, I. (2020) “Formulary for a New Urbanism” in T. McDonough (ed) The Situationists and the City: A Reader. Verso. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3785848/the-situationists-and-the-city-a-reader-pdf

Coverly, M. (2018) Psychogeography. Oldcastle Books. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1707720/psychogeography-pdf

Debord, G. (2020) “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography” in T. McDonough (ed) The Situationists and the City: A Reader. Verso. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3785848/the-situationists-and-the-city-a-reader-pdf

Grøtta, M. (2015) Baudelaire's Media Aesthetics: The Gaze of the flâneur and 19th-Century Media. Bloomsbury Academic. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/869007/baudelaires-media-aesthetics-the-gaze-of-the-flneur-and-19thcentury-media-pdf

Gieseking, J. J. et al. (2014) The People, Place, and Space Reader. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1545507/the-people-place-and-space-reader-pdf

Mitchell, P. (2013) Cartographic Strategies of Postmodernity: The Figure of the Map in Contemporary Theory and Fiction. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1672561/cartographic-strategies-of-postmodernity-the-figure-of-the-map-in-contemporary-theory-and-fiction-pdf

Nunes, M. (2020) “Ephemeral cities: Postmodern urbanism and the production of online space,” in David Holmes (ed) Virtual Globalization. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1699088/virtual-globalization-virtual-spacestourist-spaces-pdf

Reynolds, G.W.M. (2016) The Mysteries of London, vol 1. Perlego. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1848503/the-mysteries-of-london-v-14-pdf

Reynolds, G.W.M. (2016) The Mysteries of London, vol 2. Perlego. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1848483/the-mysteries-of-london-v-24-pdf

Sinclair, I. (2017) The Last London: True Fictions from an Unreal City. Oneword Publications. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1394664/the-last-london-true-fictions-from-an-unreal-city-pdf

Sinclair, I. (2018) Living with Buildings: And Walking with Ghosts – On Health and Architecture. Wellcome Collection. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3592582/living-with-buildings-and-walking-with-ghosts-on-health-and-architecture-pdf

Stevenson, R. L. (2015]) Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. 3rd edn. Broadview Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2030514/strange-case-of-dr-jekyll-and-mr-hyde-third-edition-pdf

Sue, E. (2010) The Mysteries of Paris, vol 1. Perlego. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1849993/the-mysteries-of-paris-illustrated-with-etchings-vol-1-pdf

Sue, E. (2010) The Mysteries of Paris, vol 2. Perlego. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1850004/the-mysteries-of-paris-illustrated-with-etchings-vol-2-pdf

Sue, E. (2010) The Mysteries of Paris, vol 3. Perlego. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1849983/the-mysteries-of-paris-illustrated-with-etchings-vol-3-pdf

Sue, E. (2010) The Mysteries of Paris, vol 4. Perlego. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1849972/the-mysteries-of-paris-illustrated-with-etchings-vol-4-pdf

Sue, E. (2010) The Mysteries of Paris, vol 5. Perlego. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1850001/the-mysteries-of-paris-illustrated-with-etchings-vol-5-pdf

Sue, E. (2010) The Mysteries of Paris, vol 1. Perlego. Available at.: https://www.perlego.com/book/1849973/the-mysteries-of-paris-illustrated-with-etchings-vol-6-pdf

Illustrations and images

Guy Debord (1957) "The Naked Map", Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 4.0)

PhD, English Literature (Lancaster University)

Sophie Raine has a PhD from Lancaster University. Her work focuses on penny dreadfuls and urban spaces. Her previous publications have been featured in VPFA (2019; 2022) and the Palgrave Handbook for Steam Age Gothic (2021) and her co-edited collection Penny Dreadfuls and the Gothic was released in 2023 with University of Wales Press.