What is Guy Debord's Theory of the Spectacle?

PhD, English Literature (Lancaster University)

Date Published: 12.07.2023,

Last Updated: 07.02.2024

Share this article

Defining the spectacle

In the opening to Influencer (Harder, 2022), social media influencer, Maddison, posts a series of videos chronicling her experience in Thailand. She tells her fans,

"Traveling is all about experiencing new things, pushing your own self boundaries. My goal this year would be to definitely travel more. You're so limited if you don't get out to the world and experience it for yourself." (Influencer, 2022)

What Maddison’s following cannot see, however, is that behind the camera she rarely leaves her luxury hotel and spends all her time eating Western food, taking selfies, and being upset about her current relationship troubles. This is an example of what Guy Debord refers to as “the spectacle.” In simple terms, the spectacle describes the social relations between people, mediated through images. In Influencer, Maddison is not living the authentic life she is preaching; she is far more interested in curating an online persona than enjoying her vacation. However, it is important to note that the spectacle does not solely refer to celebrity culture and mass media. Instead, as this guide will go on to explore, it is omnipresent in our political, social, and economic lives.

Guy Debord discusses the notion of the spectacle in his work The Society of the Spectacle (1967). This work became a seminal text for the group Situationist International (1957–72) one of the most radical organizations in the twentieth century. This alliance of avante-garde writers, philosophers, and artists was primarily known for its critique of capitalism, and Debord’s analysis of the inauthenticity of life under consumer capital was a significant part of their legacy. For Debord, our authentic relationships have been replaced with representations and signifiers of those relationships. Debord argues that,

The whole life of those societies in which modern conditions of production prevail presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. All that once was directly lived has become mere representation. (1967, [2020])

Guy Debord

The whole life of those societies in which modern conditions of production prevail presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. All that once was directly lived has become mere representation. (1967, [2020])

Debord here mirrors the opening lines of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital (1867, [2012]) which reads,

[t]he wealth of societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails appears as an “immense collection of commodities.” (1867, [2012])

Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels

[t]he wealth of societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails appears as an “immense collection of commodities.” (1867, [2012])

By echoing Marx, Debord indicates that his theory will be an extension of Marx’s work on commodity fetishism. Whilst aligning himself with Marx, Debord illustrates how the nature of capitalism, and the society it produces, has changed over the course of the century. Debord argues that in late capitalist societies, the consumer attempts to acquire an image, rather than the product itself. As life is a series of spectacles, according to Debord, all we have under post-war capitalism is representation where there once were authentic, lived experiences.

Beyond Marxism, Debord’s work was influenced by the Critical Theory of Frankfurt School scholars like Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer; Adorno and Horkheimer’s critique of the culture industry shares many assumptions with Debord’s work on the spectacle. Postmodernist Jean Baudrillard’s work on the simulacra/simulacrum was also highly influential on Debord’s work. For more on Baudrillard, see our guide “What is Postmodernism?”. The Society of the Spectacle takes its place within a body of twentieth-century scholarship that explored consumerism under late-stage capitalism and our ability (or inability) to distinguish representation from reality.

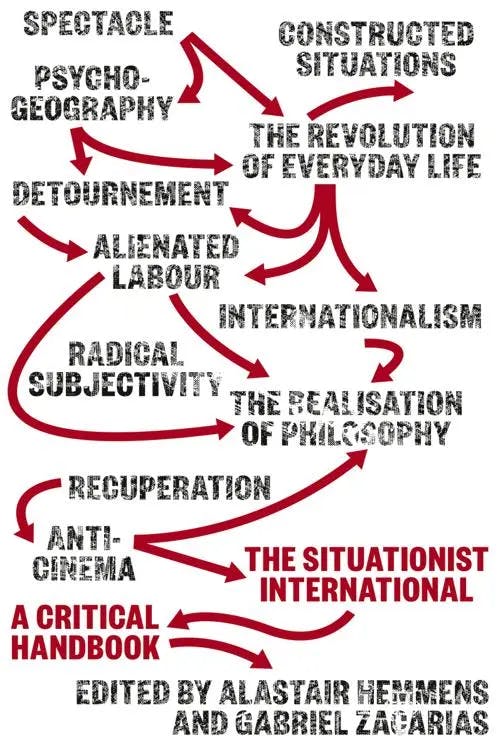

However, as Alastair Hemmens and Gabriel Zacarias explain in The Situationist International (2020), Debord’s work distinguishes itself from its predecessors. They write,

Debord believes that our progressive domination of nature has developed so closely in dialectical relation with the progress of knowledge that we have essentially created a speculative material world [...] Philosophy claimed that the world could only be known through its images, its forms of appearance, but now such images are industrially produced and widely circulated to serve the purpose of abstract wealth creation. The sensible world itself essentially becomes an appearance. The subject can no longer directly access the objective world, rather a series of images, of apparent phenomena, are offered to delight the spectator’s eyes. (Hemmens and Zacarias, 2020)

Edited by Alastair Hemmens & Gabriel Zacarias

Debord believes that our progressive domination of nature has developed so closely in dialectical relation with the progress of knowledge that we have essentially created a speculative material world [...] Philosophy claimed that the world could only be known through its images, its forms of appearance, but now such images are industrially produced and widely circulated to serve the purpose of abstract wealth creation. The sensible world itself essentially becomes an appearance. The subject can no longer directly access the objective world, rather a series of images, of apparent phenomena, are offered to delight the spectator’s eyes. (Hemmens and Zacarias, 2020)

Debord, therefore, argues that accessing the real world is no longer possible as all we experience is mediated through a series of manufactured images.

Debord argues that even our leisure time is used to engage in the spectacle and curate our image. He writes,

The social image of the consumption of time is for its part exclusively dominated by leisure time and vacations [...]Yet even in such special moments, ostensibly moments of life, the only thing being generated, the only thing to be seen and reproduced, is the spectacle – albeit at a higher-than-usual level of intensity. And what has been passed off as authentic life turns out to be merely a life more authentically spectacular. (1967, [2020])

Guy Debord

The social image of the consumption of time is for its part exclusively dominated by leisure time and vacations [...]Yet even in such special moments, ostensibly moments of life, the only thing being generated, the only thing to be seen and reproduced, is the spectacle – albeit at a higher-than-usual level of intensity. And what has been passed off as authentic life turns out to be merely a life more authentically spectacular. (1967, [2020])

Vacations become consumable goods and are packaged in this way; we see advertisements by travel agents selling a particular image to the consumer. Advertisements focusing on extravagance, relaxation, and luxury allow the consumer to imagine themselves, and represent themselves, as wealthy and successful, with an enviably decadent lifestyle. Equally, advertisers may allure potential travelers with promises of exhilarating adventures to see historic landmarks, helping the consumer cultivate their own image as a cultured explorer—experienced, exciting, thrill-seeking. In short, capitalism offers a persona available to purchase. What we see as a result is the spectacle: a series of images of someone else’s trip which do not necessarily reflect reality. Even the traveler’s own experience does not even resemble a lived experience as their understanding of the place is augmented through the mechanizations of the tourist industry.

Debord's different types of spectacle

For Debord, the spectacle could be concentrated, diffuse, or integrated, the latter of which Debord added twenty years after the original publication of The Society of the Spectacle.

Concentrated spectacle

The concentrated spectacle is most associated with bureaucratic capitalism, a system in which the wealthy, ruling elite use government resources to further their own interests, often at the expense of the rest of the population. Debord writes,

The dictatorship of the bureaucratic economy cannot leave the exploited masses any significant margin of choice because it has had to make all the choices itself, and because any choice made independently of it, even the most trivial – concerning food, say, or music – amounts to a declaration of war to the death on the bureaucracy. This dictatorship must therefore be attended by permanent violence. Its spectacle imposes an image of the good which is a résumé of everything that exists officially, and this is usually concentrated in a single individual, the guarantor of the system’s totalitarian cohesiveness. (1967, [2020])

Conformity, then, is at the core of the concentrated spectacle. This conformity is enforced by a combination of state-sanctioned violence and propagandist images of the leader as an “absolute celebrity” (1967, [2020]). In this cult of personality,

Everyone must identify magically with this absolute celebrity – or disappear. For this figure is the master of not-being-consumed, and the heroic image appropriate to the absolute exploitation constituted by primitive accumulation accelerated by terror. (Debord, 1967, [2020])

In “Raging On: The Politics of Violence in the Work of Jesusa Rodríguez and Liliana Felipe,” Diana Taylor points to the Argentine military dictatorship (1976–1983) and its three Junta leaders as a prime example of the concentrated spectacle. Taylor writes,

The Junta leaders projected themselves as ‘Fathers’ of the Nation, defending ‘her’ from subversive enemies (communists, labour leaders, students, feminists, gays, and ‘others’). Subversives were the enemy, and this was a ‘war’. Everything was spelled out, dictated as it were, ordered into being. Curfews governed time. Dress codes imposed an acceptable look on the population [...] Artists and intellectuals were disappeared, threatened, and/or exiled. The terror system ran like clockwork. Its centrifugal nature contributed to the feeling that everyone was always under surveillance. (Taylor, 2017)

Edited by Elin Diamond, Denise Varney & Candice Amich

The Junta leaders projected themselves as ‘Fathers’ of the Nation, defending ‘her’ from subversive enemies (communists, labour leaders, students, feminists, gays, and ‘others’). Subversives were the enemy, and this was a ‘war’. Everything was spelled out, dictated as it were, ordered into being. Curfews governed time. Dress codes imposed an acceptable look on the population [...] Artists and intellectuals were disappeared, threatened, and/or exiled. The terror system ran like clockwork. Its centrifugal nature contributed to the feeling that everyone was always under surveillance. (Taylor, 2017)

The spectacle, in its concentrated form, is created through tyranny and censorship. The ruling elite, according to Debord, are able to manufacture images of themselves as saviors and protectors of the people, whilst producing images of those who stand against them as transgressive enemies. This constitutes a type of spectacle as there is no way of discerning what is reality and what is a fiction created by the state to maintain control of the population.

Diffuse spectacle

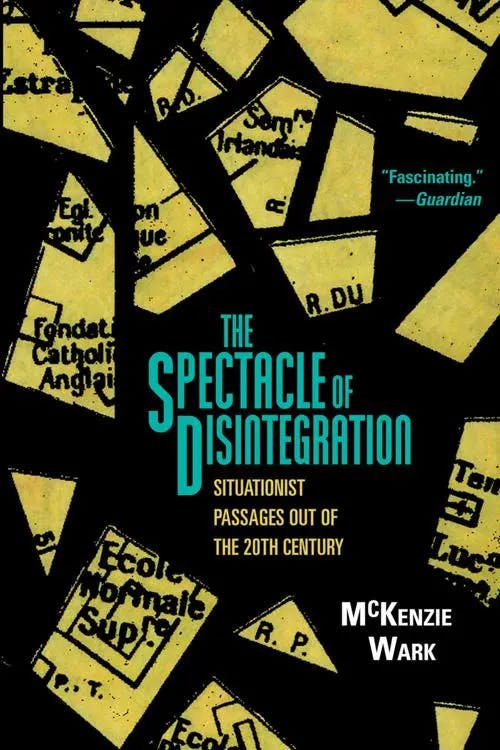

While the concentrated spectacle operates primarily through violence, the diffuse spectacle, instead, seduces and entices through an “abundance of commodities” (Debord, 1967, [2020]). The diffuse spectacle, Debord argues, is more dominant than the concentrated spectacle. Rather than the spectacle demanding the population obey a charismatic leader, this type of spectacle attempts to control the people through consumption. In The Spectacle of Disintegration (2013), McKenzie Wark argues that the diffuse spectacle has replaced the concentrated spectacle:

Big Brother is no longer watching you. In His place is little sister and her friends: endless pictures of models and other pretty things.

McKenzie Wark

Big Brother is no longer watching you. In His place is little sister and her friends: endless pictures of models and other pretty things.

This endlessness is alluring to the consumer as it draws attention to the “grandeur of commodity production in general” (Debord, 1967, [2020]). As Debord goes on to explain, however, the claims offered from advertisers are often “jostling for position on the stage” are “not always compatible,” and different commodities may “simultaneously promote conflicting approaches to the organization of society” (1967, [2020]).

Unlike a totalitarian state wherein the visage of a single supreme leader is sold to the people, in the diffuse spectacle, different brands compete for the consumer’s attention. Here, the illusion of choice is what is really being sold. Debord further writes,

[...] the already questionable satisfaction allegedly derived from the consumption of the whole is adulterated from the outset because the real consumer can only get his hands on a succession of fragments of this commodity heaven – fragments each of which naturally lacks any of the quality ascribed to the whole. (1967, [2020])

Guy Debord

[...] the already questionable satisfaction allegedly derived from the consumption of the whole is adulterated from the outset because the real consumer can only get his hands on a succession of fragments of this commodity heaven – fragments each of which naturally lacks any of the quality ascribed to the whole. (1967, [2020])

As such, there can never be any real form of gratification. This is true of both the diffuse and concentrated forms of spectacle. In the consumer world, the “must have” products quickly become replaced by newer versions leading to an endless pursuit of commodities. In totalitarian states (i.e., the concentrated form of spectacle), leaders and ideologies are equally replaceable:

Stalin, just like any obsolete product, can be cast aside by the very forces that promoted his rise. Each new lie of the advertising industry implicitly acknowledges the one before. Likewise every time a personification of totalitarian power is eclipsed, the illusion of community that has guaranteed that figure unanimous support is exposed as a mere sum of solitudes without illusions. (Debord, 1967, [2020])

The spectacle, therefore, can be further characterized by its impermanence.

Integrated spectacle

In 1988, Debord published Comments on the Society of the Spectacle in which he introduced a third type of spectacle: the integrated spectacle. The integrated spectacle emerges as the two other forms of spectacle (concentrated and diffuse) evolve: the concentrated spectacle moves away from a clear ideology and towards occultism, and the diffuse spectacle has permeated almost all forms of “socially produced behaviour and objects” (Debord, 1988, [2020]). The integrated spectacle is a combination of these two forms and has infiltrated all aspects of our lives:

"When the spectacle was concentrated, the greater part of surrounding society escaped it; when diffuse, a small part; today, no part. The spectacle has spread itself to the point where it now permeates all reality." (1988, [2020])

As an example of the integrated spectacle Debord offers the restoration of historical sites and art works:

"Being the richest and the most modern, the Americans have been the main dupes of this traffic in false art. And they are exactly the same people who pay for restoration work at Versailles or in the Sistine Chapel[...] the tendency to replace the real with the artificial is ubiquitous. In this regard, it is fortuitous that traffic pollution has necessitated the replacement of the Marly Horses in place de la Concorde, or the Roman statues in the doorway of Saint-Trophime in Aries, by plastic replicas. Everything will be more beautiful than before, for the tourists’ cameras." (1988, [2020])

Guy Debord

"When the spectacle was concentrated, the greater part of surrounding society escaped it; when diffuse, a small part; today, no part. The spectacle has spread itself to the point where it now permeates all reality." (1988, [2020])

As an example of the integrated spectacle Debord offers the restoration of historical sites and art works:

"Being the richest and the most modern, the Americans have been the main dupes of this traffic in false art. And they are exactly the same people who pay for restoration work at Versailles or in the Sistine Chapel[...] the tendency to replace the real with the artificial is ubiquitous. In this regard, it is fortuitous that traffic pollution has necessitated the replacement of the Marly Horses in place de la Concorde, or the Roman statues in the doorway of Saint-Trophime in Aries, by plastic replicas. Everything will be more beautiful than before, for the tourists’ cameras." (1988, [2020])

Reality in the integrated spectacle is shaped by commodification. The restoration and architectural design of cities is conducted with the consumer in mind. As Hemmens and Zacarias explain,

The restoration of historical cities and monuments is now chiefly oriented towards the economic criteria of mass consumption instead of the traditional paradigms of beauty and authenticity that had previously been central to the preservation of artistic and historical knowledge. (2020)

The spectacle, therefore, results in the loss of historic fact and social knowledge. By eradicating, restoring, or otherwise adapting historical artifacts and monuments for public consumption, we alter their significance and our understanding of history. We are, in actuality, looking at a representation and believing it to be reality.

Debord characterizes the integrated spectacle as having the combined effect of five core features: “incessant technological renewal; integration of state and economy; generalised secrecy, unanswerable lies; an eternal present” (1988, [2020]). We will now explore each of these features.

Incessant technological renewal

Following the Second World War, technology’s progression has “reinforced spectacular authority” (Debord, 1988, [2020]). Our reliance on technology has meant that millions put their faith in a comparatively small group of experts and specialists. It is from this group of technological savants that we seek information when we need to upgrade our phones and determine the best technology to use. These experts help to facilitate constant technological renewal which, in turn, maintains the capitalist system.

Integration of the state and economy

Debord argues that the state and the economy, having merged, are now equipped with the “greatest common advantages in every field” and, as such, “it is absurd to oppose them, or to distinguish between their reasons and follies” (1988, [2020]).

Debord expands,

All experts serve the state and the media and only in that way do they achieve their status. (1988, [2020])

As expert opinions are so heavily influenced by the media and the state, it becomes impossible for the individual to tell which information has been falsified.

The final three features of an integrated society, Debord argues, come about as a result of the merger between state and economy.

Generalised secrecy

Secrecy is “the most vital operation” of the spectacle (Debord, 1988, [2020]). Debord points out that a certain degree of secrecy is accepted, but that people are typically unaware of how pervasive this secrecy is. According to Debord, the public (or spectators, as he calls them) remains ignorant of the fact that their entire reality is based upon falsehoods.

Unanswerable lies

In the integrated spectacle, the false is so pervasive that the truth ceases to exist in almost all facets of life. As the spectacular society has emerged, historical knowledge and objective facts have been altered to such a degree that there is no stable frame of reference. As such, it becomes difficult for the spectator to even check lies, or suspected lies, of advertisers, the media, or politicians. Truth, as Debord sees it, “has been reduced to the status of pure hypothesis” (1988, [2020]).

Debord’s arguments become more evident as some writers argue that we are currently living in a post-truth society, evidenced by discussions surrounding “fake news,” “alternative facts,” and the Donald Trump presidency (2017–2021). For more on this, see Johan Farkas and Jannick Schou’s Post-Truth, Fake News and Democracy (2019).

An eternal present

The continuous circulation of information and trends keeps the spectator in the constant present. The spectator is kept occupied by trivial things to distract from what is genuinely important. Debord writes,

[...] news of what is genuinely important, of what is actually changing, comes rarely, and then in fits and starts. It always concerns this world’s apparent condemnation of its own existence, the stages in its programmed self-destruction. (1988, [2020])

Guy Debord

[...] news of what is genuinely important, of what is actually changing, comes rarely, and then in fits and starts. It always concerns this world’s apparent condemnation of its own existence, the stages in its programmed self-destruction. (1988, [2020])

We can see this today with news media outlets covering social media stories and celebrity gossip. Warnings of future crises, such as climate change, hold little interest as the spectacle has created a world where there is no past nor future.

The self, reality, and the celebrity

For Debord, mass media is the spectacle’s most obvious and superficial form. The spectacle, above all else, is a social structure which produces appearance. As Debord explains, the spectacle tells us: “‘Everything that appears is good; whatever is good will appear (Debord, 1967).’” Appearance, then, becomes more valuable than reality. In today’s world dominated by celebrities and content creators, images and representation begin to replace our authentic reality. Though Debord may not have predicted the advent of social media and the rise of the influencer, he understood the role celebrities play in the spectacle, branding themselves and selling their image:

Media stars are spectacular representations of living human beings, distilling the essence of the spectacle’s banality into images of possible roles. Stardom is a diversification in the semblance of life – the object of an identification with mere appearance which is intended to compensate for the crumbling of directly experienced diversifications of productive activity. (1967, [2020])

Guy Debord

Media stars are spectacular representations of living human beings, distilling the essence of the spectacle’s banality into images of possible roles. Stardom is a diversification in the semblance of life – the object of an identification with mere appearance which is intended to compensate for the crumbling of directly experienced diversifications of productive activity. (1967, [2020])

Celebrities become a universal goal. Celebrity culture perpetuates capitalism’s grand narrative by promising that social labor and commodification of the self will result in fame, fortune, perfection.

As Richard Stivers writes,

The celebrity is a caricature of the human, a visual stereotype. Technical desire and imitation are channeled into experimental consumption, especially of visual images: I become what I behold and consume. (2020)

Richard Stivers

The celebrity is a caricature of the human, a visual stereotype. Technical desire and imitation are channeled into experimental consumption, especially of visual images: I become what I behold and consume. (2020)

The spectator believes they can become like the celebrity through consuming the celebrity ( reading about their professional and personal lives, following them on social media, etc.). However, as Debord points out, the celebrity, like the commodity, has been carefully manufactured and sold to the public. The idea that everyone can obtain the celebrity lifestyle is, in fact, an illusion.

The spectacle today

Debord’s theory of the spectacle is now more relevant than ever. Not only are consumers bombarded with images of celebrity lifestyles and advertised products, but also technological advancements have blurred the line between reality and representation even further. From the introduction of hyper-realistic graphics in video games to virtual reality technology to immersive online spaces populated by avatars, such as the Metaverse, we can see that real, authentic experiences become substituted for image and representation.

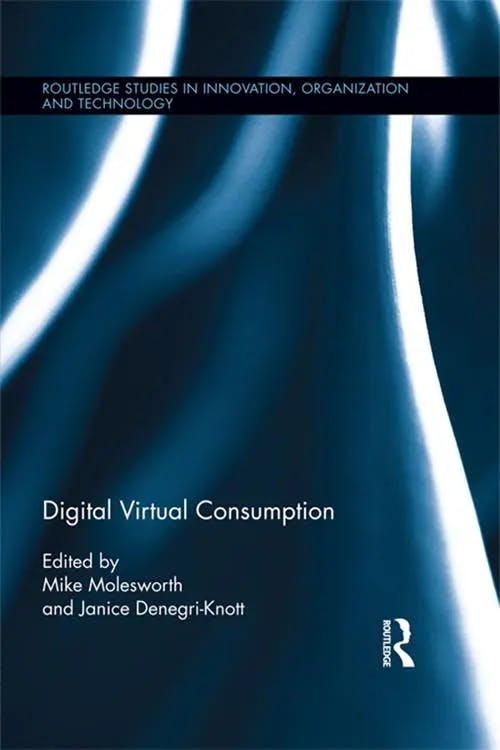

Our immersion in the virtual world, particularly in gameplay, has been seen by some as evidence of the spectacle’s continued presence and ability to erode our own creative output. In “First Hand Shoppers”, Mike Molesworth writes,

[...] the player escapes from the frustrations and inequalities of the routines of work only through new routines of leisure consumption, designed, packaged, and handed to him or her in the form of the latest spectacular videogame. (Digital Virtual Consumption, 2013)

Edited by Mike Molesworth & Janice Denegri Knott

[...] the player escapes from the frustrations and inequalities of the routines of work only through new routines of leisure consumption, designed, packaged, and handed to him or her in the form of the latest spectacular videogame. (Digital Virtual Consumption, 2013)

However, Molesworth interrogates what we mean by “meaningless consumption,” considering whether this line of criticism is “just nostalgia for an imagined less commercial age, or an elitist call for more worthy activities?” (2013).

It is not only new forms of entertainment that have developed since the time of Debord’s writing, but the ways in which we receive, understand, and consume news media. A key critic in this area is Douglas Kellner. In Media Spectacle (2013), Kellner writes,

Social and political conflicts are increasingly played out on the screens of media culture, which display spectacles such as sensational murder cases, terrorist bombings, celebrity and political sex scandals, and the explosive violence of everyday life.

Douglas Kellner

Social and political conflicts are increasingly played out on the screens of media culture, which display spectacles such as sensational murder cases, terrorist bombings, celebrity and political sex scandals, and the explosive violence of everyday life.

He further notes that we are seeing the rise of the “megaspectacle” (i.e., spectacles which define a generation) and cites cases such as the O.J. Simpson trial as an example of such an event.

With our seemingly unlimited access to online content, it is becoming more and more difficult to discern reality from appearance. However, while Debord was skeptical of our ability to even access reality, technological advances and widespread forms of communication via digital platforms offer some hope. While politicians and celebrities may present an enhanced image of themselves, misrepresentations or outright misinformation are becoming harder to feign as spectators aim to debunk such lifestyles using online fact checkers.

The replacement of authentic life with images, as Debord theorized, has transformed our modern lives; the spectacle influences everything from what brands we choose to buy to to who we vote for in elections. The spectacle has advanced more than Debord likely could have ever conceived and now, with platforms such as TikTok allowing everyone to mimic and experience the celebrity lifestyle, it is more pervasive than ever.

Further reading on Perlego

Media Spectacle and the Crisis of Democracy: Terrorism, War, and Election Battles (2015) by Douglas Kellner

The Spell of Capital: Reification and Spectacle (2017) edited by Samir Gandesha and Johan Frederik Hartle

The Spectacle of the Real: From Hollywood to 'Reality' TV and Beyond (2005) by Geoff King

What is the spectacle in simple terms?

Who were the Situationists?

What are the key types of spectacle?

What is an example of spectacle?

Bibliography

Debord, G. (2020) The Society of the Spectacle, translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Zone Books. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1636424/the-society-of-the-spectacle-pdf

Debord, G. (2020) Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, translated by Malcolm Imrie. Verso. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3785655/comments-on-the-society-of-the-spectacle-pdf

Influencer (2022) Directed by Kurtis David Harder. Available on Amazon Prime.

Hemmens, A. (2019) The Critique of Work in Modern French Thought: From Charles Fourier to Guy Debord. Palgrave Macmillan. Available at:

Hemmens, A., and Zacarias, G. (eds.) (2020) The Situationist International: A Critical Handbook. Pluto Press. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/1419996/the-situationist-international-a-critical-handbook-pdf

Kellner, D. (2003) Media Spectacle. Routledge. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/1618453/media-spectacle-pdf

Marx, K. (2012) Das Kapital: A Critique of Political Economy. Gateway Editions. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/784600/das-kapital-a-critique-of-political-economy-pdf

Taylor, D. (2017) “Raging On: The Politics of Violence in the Work of Jesusa Rodríguez and Liliana Felipe” in Diamond, E., Varney, D., and Amich, C. (eds.) Performance, Feminism and Affect in Neoliberal Times. Palgrave Macmillan. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/3491353/performance-feminism-and-affect-in-neoliberal-times-pdf

Wark, M. (2013) The Spectacle of Disintegration: Situationist Passages out of the Twentieth Century. Verso. Available at:

PhD, English Literature (Lancaster University)

Sophie Raine has a PhD from Lancaster University. Her work focuses on penny dreadfuls and urban spaces. Her previous publications have been featured in VPFA (2019; 2022) and the Palgrave Handbook for Steam Age Gothic (2021) and her co-edited collection Penny Dreadfuls and the Gothic was released in 2023 with University of Wales Press.