What is Cubism?

PhD, Media Arts (Royal Holloway, University of London)

Date Published: 27.03.2023,

Last Updated: 16.07.2024

Share this article

Defining Cubism

Cubism was a modern art movement that emerged in France in the first decade of the 20th century, often heralded as one of the most important moments in art history. Among its most significant influences were the works of Paul Cézanne and the aesthetic of African art, although Cubism is most renowned for its innovation, its intrepid journey into new artistic territories. A foundational avant-garde art movement, Cubism signified a change in the style and potential of Western painting. Before the avant-garde, artists had largely been striving towards accurate and naturalist representations of their subjects. Cubism marked an early example of a stylistically recognizable departure from representational art, led by Georges Braque and, most famously, Pablo Picasso.

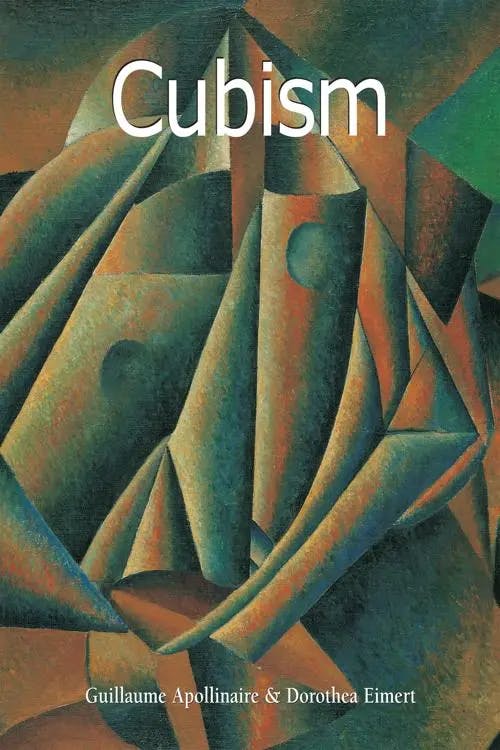

In Cubism, Guillaume Apollinaire and Dorothea Eimert explain how, between 1909 and 1912, Braque and Picasso:

“separated their art from everything real without turning completely to abstraction,” (2014). Mostly painting figures and still lifes, the Cubists, Appollinaire and Eimert assert, “layered views from many angles in order to capture the subject from all sides. They analysed the object and brought it to the canvas as a fragmented picture.” (2014)

Guillaume Apollinaire, Dorothea Eimert

“separated their art from everything real without turning completely to abstraction,” (2014). Mostly painting figures and still lifes, the Cubists, Appollinaire and Eimert assert, “layered views from many angles in order to capture the subject from all sides. They analysed the object and brought it to the canvas as a fragmented picture.” (2014)

This style can be observed in Picasso’s famous paintings of angular figures and disjointed objects.

The name “Cubism” came from a derogatory exhibition review written in 1908 that accused Braque of “reducing everything […] to cubes” (Vauxcelles, 1908). Although it was not supposed to flatter the artist, Braque and Picasso reappropriated the term to describe their art.

The Cubist movement is often understood in two parts. The period from 1909–1912 is referred to as “analytic Cubism,” which saw objects and figures deconstructed and reconstructed from new perspectives. Before Cubism, Western painting showed figures and objects as they appear to the eye: from a single perspective. Early Cubism was not an expression of pure abstraction — it still depicted figures and objects — but it represented them in such a way that multiple perspectives were shown at once. This resulted in a style that was fragmented and geometric; at once recognizable and strange. From 1912 onward, Cubism would become more abstract. Characterized as “synthetic Cubism,” this new development in the movement welcomed more varied materials and techniques, incorporating bright colors, simpler shapes, and raw materials into the canvas. Cubism sought to change the relationship of art to the world, emphasizing the two dimensionality of the canvas and the limitations of linear perspective. It is often considered the precursor to many avant-garde art movements that followed such as Dada, Futurism, Constructivism, and Art Deco.

Cubism’s influences

Braque was heavily influenced by French artist Paul Cézanne and his unique renderings of the natural world at the end of the 19th century. Jane Bingham asserts that Cézanne’s “work provided a bridge between the relatively short-lived Impressionist movement and the emergence of later styles” (2019). The use of unnatural cylindrical and geometric shapes to represent scenes in nature was a break in the tradition of form and representation. This break in tradition was something the Cubists continued to perpetuate. Most significantly, Cubism can be understood as a response to Cézanne’s famous proposal that “you must see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone” (1904, [1976]). He suggested that all the various forms of the natural world could be reduced to geometrical shapes, what Appolinaire and Eirmert describe as “the artist’s response to the changed preconditions of science regarding space and time” (2014). The avant-garde was largely a response to the rise of materialism and rational thinking associated with modernity. With the arrival of new modes of transportation and the accelerated spread of information, time and space in modernity was condensed, made more malleable. Modern mechanization made such advancements possible, and so informed a new way of looking at the world, including the world of nature. This change in the treatment of the natural world was something the Cubists explored in their figurative and still life paintings based on the earlier works of Cézanne .

Picasso was equally inspired by African and Indigenous art . He observed the way that the African masks at the ethnographic museum in Paris were both representative of a face and highly angular and exaggerated. These mask faces became a recognizable feature of Cubism. Faces in Cubist paintings have exaggerated features, high contrasts between light and dark and layered and disorienting perspective, features which Picasso encountered in those Tribal masks.

Picasso’s observations in the ethnographic museum precipitated an obsession with collecting objects. In Picasso, Patrick O’Brian describes how the artist’s,

flat was piled high with things like guitars; mandolins; boxes; chests; popular and colored prints in frames of plaited straw; countless African and Oceanic figures. (2012)

Patrick O'Brian

flat was piled high with things like guitars; mandolins; boxes; chests; popular and colored prints in frames of plaited straw; countless African and Oceanic figures. (2012)

These collected objects were to act as inspiration for Picasso’s paintings and sculptures.

Cubists also emulated the way African and Oceanic sculpture played with perspective and dimension. They were at once abstract and figurative, elongating or contracting limbs and torsos, shrinking or exaggerating heads. Where the Cubists emphasized the two-dimensional nature of canvas, Tribal sculpture often gave its figures a two-dimensional appearance, compressing perspective into one field of vision.

This ancient artistic inspiration offered the avant-garde an escape from the cultural standards of classical Western sculpture. Western art, from classicism to the renaissance, favored smooth, soft, and precise representation. The avant-garde hoped to challenge the standards that this art set, Cubism partly doing so through the appropriation of African and Oceanic artistic figuration. Not only did African and Oceanic art explore dimension and perspective, but it also incorporated a series of natural materials like wood, metals, and ivory. Synthetic Cubists also sought to use raw materials in their artistic works. Through this appropriation, Cubism challenged the dominant Western aesthetic and ushered in a new function of Western art, one not based around pleasing traditional and elite artistic tastes but rather exploring beyond what the eye can see from a single limited perspective.

Examples of Cubist works

Picasso is one of the most famous avant-garde artists, and his works are certainly amongst the most recognizable of the Cubist movement. His painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) is often referred to as the “first Cubist picture” and is exemplary of what became the aesthetic of Cubism (Barr, Cubism and Abstract Art, 2019).

It shows five naked women whose angular bodies crowd an exaggeratedly two-dimensional space. In comparison to the nude motif of classical painting, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon proved striking in its disregard of the soft shapes and colors that previously constituted aesthetic beauty. The faces of the women are thought to resemble the African masks that Picasso was so inspired by. Exaggerated features and colors as well as the angular and multi-dimensional aspects of the women’s faces challenged the naturalist beauty standards of Western art.

Guernica (1937) is another of Picasso’s most famous works. The huge canvas shows a greyscale scene of violence in response to the German bombing of the Basque town that the painting was named after. Picasso was not particularly political, atypical for an avant-garde artist at the time, but Guernica was certainly an anti-war symbol, condemning the violence of the Nazis and bringing attention to the horrors of the Spanish civil war. Guernica shows the power that Cubism’s strange shapes, angles, and semi-abstract forms had to horrify, move, and inform viewers.

In the early (analytic) stages of Cubism, Braque tended to paint more abstract-leaning works than Picasso. Man with a Guitar (1911–1912) is one such example. If it weren’t for the descriptive title, what the painting depicts would not be easily decipherable. Man with a Guitar shows fragments and suggestions of vaguely human and instrument features amongst cylindrical and spherical shapes. The lines that fragment and slice the brown-grey shapes come together to create the outline of the man and his guitar. In typical Cubist fashion, Braque subverted the illusion of perspective that painting had previously depicted, instead oscillating between unnatural angular depth and two-dimensional space.

These works that partly constitute the Cubist canon exemplify the way that the movement revolutionized the art world. With the unconventional influence of what was considered “primitive” art, the denaturalization of objects and figures, and the reinstatement of two-dimensional canvas space, Cubism challenged the standards and purpose of Western art.

The lasting influence of Cubism

Cubism evolved to use many different mediums to produce art of varying degrees of abstraction, influencing not only the trajectory of the avant-garde but of art in general. Cubism’s later incorporation of everyday materials is often thought to have inspired the Dadaist readymades while elements of the Cubist tendency to denaturalize objects can be observed in Surrealism. As Willard Bohn asserts in The Early Avant-Garde in Twentieth-Century Literature and Art, Cubism’s aesthetic approach was so radical that it “exerted a disproportional influence on modern art” (2018).

Not only did Cubism set the scene for the incredibly influential movements of the avant-garde that proceeded, but it is widely accepted to have changed the way that works of art interact with their subjects and to have confronted the limiting expectations of aesthetic beauty. This aesthetic revolution was one that subverted the naturalism and objectivity of previously existing art and challenged the eye of the viewer to observe distorted and fragmented images from a seemingly illogical and manifold point of view.

R. Bruce Elder describes this new artistic order in Cubism and Futurism, asserting that,

Cubism understands the new art not as imitating the appearance of reality, but rather as offering a homology between the way the painting comes to be (that is, the transformation of reality into art) and the process by which perception is formed and an object emerges in awareness. The homology between these processes suggests the collusion of the senses and the imagination. (2018)

R. Bruce Elder

Cubism understands the new art not as imitating the appearance of reality, but rather as offering a homology between the way the painting comes to be (that is, the transformation of reality into art) and the process by which perception is formed and an object emerges in awareness. The homology between these processes suggests the collusion of the senses and the imagination. (2018)

The conceptual approach to art that Cubism helped initiate created a new visual language imbued with tension and metaphor, heralding a new function of art in society and the world.

Further Cubism reading on Perlego

Picasso: Selected Essays by Leo Steinberg and Sheila Schwartz.

The Picasso's Cubism by Gabriel Baldovin.

Cubism, Stieglitz, and the Early Poetry of William Carlos Williams by Bram Dijkstra.

The Age of the Avant-Garde by Hilton Kramer.

Bibliography

Bingham, Jane. (2019) Paul Cézanne. Arcturus Publishing.

Cézanne, Paul. (1976). Letters, ed. John Rewald. 4th ed. New York.

Vauxcelles, Louis. (1908) Exposition Braques. Gil Blas.

Elder, Bruce. (2018) Cubism and Futurism. Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Apollinaire, Guillaume, and Dorothea Eimert. (2014) Cubism. Parkstone International.

Danchev, Alex. (2007) Georges Braque: A Life. Penguin Books Limited

O’Brian, Patrick. (2012) Picasso. Harper Collins Publishers.

Barr, Alfred. (2019) Cubism and Abstract Art. Taylor and Francis.

Bohn, Willard. (2018) The Early Avant-Garde in Twentieth-Century Literature and Art. Taylor and Francis.

PhD, Media Arts (Royal Holloway, University of London)

Aoiffe Walsh has a PhD in Media Arts from Royal Holloway, University of London. With a background in film studies and philosophy, her current research explores British literary modernism, with a particular focus on surrealism between the wars. She has lectured and published pieces on documentary and film theory, film history, genre studies and the avant-garde.