What is Vorticism?

MA, Sociology (Freie Universität Berlin)

Date Published: 04.07.2023,

Last Updated: 01.02.2024

Share this article

Defining Vorticism

Vorticism was a small-scale, short-lived, and particularly unpopular artistic and literary movement that emerged in London just on the cusp of WWI. Its frontman and founder was writer and artist, Wyndham Lewis — a controversial and misanthropic figure with notorious ties to fascism (Raymond Williams, Politics of Modernism, 2020). Aside from Lewis, only a small handful of other artists and writers officially associated themselves with Vorticism. Yet, it remains influential and emblematic of the modernist avant-garde more broadly. Paul Edwards summarizes its importance:

In the four years from 1910 to 1914, in parallel with the social and political ferment of the times, radically new ideas and practices in the visual arts were introduced in Britain […] the climax came in the late spring of 1914, with the emergence of a genuine avant-garde movement having its own identifiable form of geometric abstraction and its own vibrant and aggressive magazine, Blast. The movement was 'Vorticism' [ …] now recognized as the high-water mark of modernism in England at least until the 1930s. (2018)

Edited by Paul Edwards

In the four years from 1910 to 1914, in parallel with the social and political ferment of the times, radically new ideas and practices in the visual arts were introduced in Britain […] the climax came in the late spring of 1914, with the emergence of a genuine avant-garde movement having its own identifiable form of geometric abstraction and its own vibrant and aggressive magazine, Blast. The movement was 'Vorticism' [ …] now recognized as the high-water mark of modernism in England at least until the 1930s. (2018)

Moreover, Vorticism is significant because it was one of the first avant-garde movements in England — where France had hitherto dominated the cultural and artistic scene.

To truly glean why Vorticism made such a splash — despite its more dubious qualities — we have to start by properly contextualizing it within the “social and political ferment of the times” out of which it emerged. Therefore, this study guide begins with an overview of the social and cultural concerns that inspired the modernist movement of which Vorticism was a part. From there, we can locate some of Vorticism’s distinctive aesthetic and conceptual features, as depicted in its seminal text, Blast (1914). Finally, this study guide offers some reflections on Vorticism’s reception and enduring legacy as an avant-garde movement.

Modernism, the avant-garde, and the makings of Vorticism

Modernism

Vorticism is considered part of a wider movement known as modernism, which began at the turn of the 20th-century, largely as a pushback against much of the Victorian sensibilities that made up the cultural status quo of the day. The modernist movement also came as a response to the rapid industrialization, urbanization, and technological changes that were fundamentally shifting the social landscape at the time in which its constituent artists were active. In particular, modernists were trying to make sense of, and capture the spirit of, these changes in their work, and they did so through a wide range of artistic, literary, architectural, and intellectual sub-movements. As historian Robin Walz observes,

[...] whatever the orientation of a particular modernist artist or movement, all share a strong impulse towards experimentation, that is, to examine, alter and transform the forms and meaning of art, literature, music, architecture or design. As a result, a high value is placed upon innovation and novelty, to make new art that transcends contemporary life and elevates the viewer, reader or audience above the mundane. (2013)

Robin Walz

[...] whatever the orientation of a particular modernist artist or movement, all share a strong impulse towards experimentation, that is, to examine, alter and transform the forms and meaning of art, literature, music, architecture or design. As a result, a high value is placed upon innovation and novelty, to make new art that transcends contemporary life and elevates the viewer, reader or audience above the mundane. (2013)

The modernists, therefore, were united by a stark departure from traditional forms and conventions in culture, instead embracing experimentation and the rejection of established norms, as put forth by the bourgeois, Edwardian elite who made up the cultural norms before the modernists came on the scene. These conventions included a value for realism and mimesis (the artistic process of imitation of mimicry); sentimentalism and morality; linearity; a romanticization of the natural world; and a focus on traditional femininity and family life. In contrast, modernism set out to challenge these values, and as Walz continues,

[…] the intellectual historian Eugene Lunn has articulated four broad dimensions to the modernist aesthetic: self-reflexivity, simultaneity, uncertainty of meaning, and dehumanisation. (2013)

In practice, this meant that modernists were known for turning traditional aesthetic forms on their heads, substituting soft depictions of femininity exemplified by painters like John William Waterhouse for bold and brash angular lines of Picasso’s Cubist works. In written form, this shift can be seen in the contrast between the mimetic and realistic prose of Alfred Tennyson and the acrostic, experimental works of modernist writers like E.E. Cummings.

Ultimately, the modernists aimed to surprise, provoke, and ruffle the feathers of a stuffy, tepid bourgeois status quo that, they believed, no longer spoke to the spirit of the times in which they were living. Modernism sought to reflect the increasing complexities, contradictions, and moral vacuousness of the rapidly changing social landscape. In turn, the avant-garde wing of modernism — of which Vorticism was most certainly a part — was at the vanguard of this assault on business as usual, and are generally distinguished by their way of taking these rebellious efforts to the greatest extreme through their experimental works.

The avant-garde

The modernist avant-garde comprised the staunchest defectors from the bourgeois cultural standards described in the previous section. They were exceptionally forward-thinking artists, writers, and intellectuals who often brashly affronted mainstream and middlebrow culture through their works. The avant-garde viewed these currents as a direct reflection of how the out-of-touch, wealthy tastemakers of the day exerted control over the mindless, docile masses (Williams, 2020). In addition, as Hilton Kramer aptly points out,

As for the avant-garde itself, its own history is anything but a singleminded tale of revolt against bourgeois values… The history of the avant-garde actually harbors a complex agenda of internal conflict and debate, not only about aesthetic matters but about the social values that govern them. (2013)

Hilton Kramer

As for the avant-garde itself, its own history is anything but a singleminded tale of revolt against bourgeois values… The history of the avant-garde actually harbors a complex agenda of internal conflict and debate, not only about aesthetic matters but about the social values that govern them. (2013)

Thus, not only did the avant-garde hold contempt for the plebeian masses and for middlebrow culture, but also, in the case of Vorticism in particular, had serious contentions even with other, less extreme modernist groups such as Impressionism and Imagism (Blast: Vorticism, 1914–1918, 2018). This is because, over time, the avant-garde saw these movements become assimilated into the mainstream. It was out of this quarrelsome spirit that Vorticism would emerge.

Rebel Artists: famous feuds and the makings of Vorticism

A death blow to Futurism

In the months leading up to the emergence of Vorticism, Lewis founded the short-lived Rebel Art Center in London. Here, he associated with other avant-garde writers and artists such as the Italian Futurist, Filippo Marinetti, who would serve as a source of foundational inspiration for the Vorticist movement. As Paul Edwards recounts, such is evident through Lewis and Marinetti’s shared draw towards dynamism and motion; embracing of modernity and the machine; and their brash, confrontational artistic and literary styles (Blast: Vorticism, 1914–1918, 2018).

Moreover, the relationship between Lewis and Marinetti was far from a collaborative one. Rather, they were embroiled in a competitive feud over their art. In particular, when Marinetti published his own manifesto under the Rebel Artist name, Lewis took it as a direct challenge to his authority, and this served as the impetus for Lewis to distinguish himself by publishing Blast, his own Vorticist manifesto, which was conceived of as a “'death blow” to Futurism (Blast: Vorticism, 1914–1918, 2018).

The vortex

The squabble between Lewis and Marinetti wasn’t the only feud that played into the makings of Vorticism. Ezra Pound, one of Vorticism’s key figures, came up with the concept of ‘the vortex’, after which the movement was named following a dramatic split with another modernist current, the Imagists. Imagism refers to,

An early-twentieth-century modernist movement in Anglo-American poetry that promoted an economy of direct, clear and precise language in poetic images over lyrical verse. (Walz, 2013)

While the general definition of Imagism may appear fairly innocuous, the precise vision for what counts as Imagist poetry spurred one of the most notorious rifts of the modernist movement between Pound and the Imagist anthology editor, Amy Lowell.

In a more moderate expression of modernist values, Lowell held a broader interpretation to Imagism and was open to a wider flexibility of form — meaning that she was interested in making the movement more widespread and accessible to the public. As an avant-gardist, Pound by contrast, was incensed by this idea, as he favored a much stricter interpretation of what Imagism should be about. In particular, he emphasized making a stark break from any traditional poetic formats and conventions as well as keeping the circle of true Imagists small and exclusive.

After a dramatic and widely publicized break from Imagism snarkily renaming it as “Amygisme,” Pound came up with the inspiration for Vorticism through honing in on the image of the vortex specifically. As Noel Stock paraphrases Pound in the biography, The Life of Ezra Pound,

There were ‘new masses of unexplored arts and facts’ pouring into the ‘vortex’ of London, he wrote, which ‘cannot help but bring about changes as great as the Renaissance changes, even if we set ourselves blindly against it. As it is, there is life in the fusion. The complete man must have more interest in things which are in seed and dynamic than in things which are dead, dying, static.’ (2013)

Noel Stock

There were ‘new masses of unexplored arts and facts’ pouring into the ‘vortex’ of London, he wrote, which ‘cannot help but bring about changes as great as the Renaissance changes, even if we set ourselves blindly against it. As it is, there is life in the fusion. The complete man must have more interest in things which are in seed and dynamic than in things which are dead, dying, static.’ (2013)

Pound believed that the vortex was the emblematic image of the modern era, as it captured the energy and dynamism of the urban environment as well as the burgeoning technological innovations of the day. In this sense, the Vorticism was an edgier, more modernistic response to Imagism.

Blast: a Vorticist Manifesto

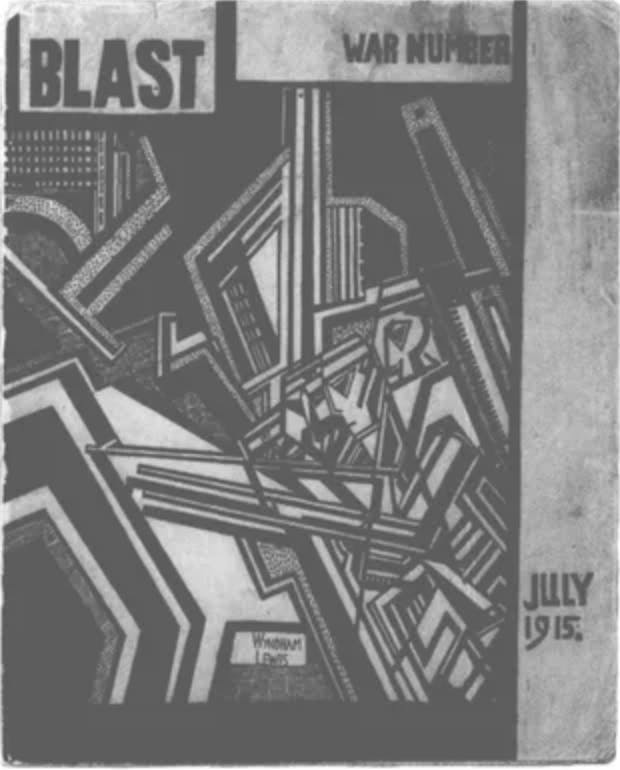

In 1914, Vorticism published its manifesto, in the form of a magazine with a hot pink cover and set in newly-minted, sans serif font. These features alone were all highly unusual for the publishing standards of the day. In fact, Lewis had a notoriously difficult time finding anyone to print it at all (Blast: Vorticism, 1914–1918, 2018). A copy of Blast was also very expensive, and taken together, these factors made it quite inaccessible to the general public. Its pages were filled with both visual and prosaic affronts on the Edwardian standards of the time, and its style was abrasive and replete with satire and mockery.

Wyndham Lewis, cover of Blast no. 2, 1915 (Karin Orchard, Blast: Vorticism, 1914–1918, 2018)

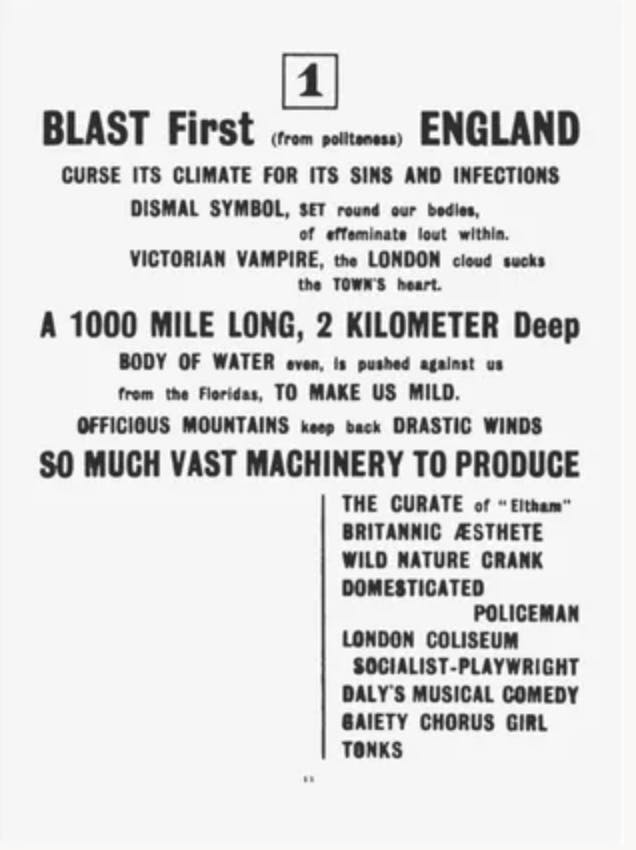

Page from Blast no. 1, 1914 (Karin Orchard, Blast: Vorticism, 1914–1918, 2018)

At first, the bluster and provocation that is Blast can be hard to follow at all, but as Karin Orchard argues,

While the first manifesto contains a good deal of disguised nonsense, its casual, mocking tone gives way to a more serious note in the second. Here is where we find the Vorticist programme clearly set out, with its list of demands and the signatures of those making them. (Orchard, “‘A Laugh Like a Bomb’: The History and the Ideas of the Vorticists” in Blast: Vorticism, 1914–1918, 2018)

Some of the themes and principles of the Vorticist programme as evident in Blast include: rejecting the status quo; individualism and the cult of the artistic genius; the masculine and the machine; and a preoccupation with violence, purity, and corruption. Below we will explore each in more detail.

Principles of Vorticism

Rejecting the status quo

In what we’ve already established was typical avant-garde fashion, the Vorticists launched a vitriolic attack on mainstream culture and established norms. In addition to the outlandish and off-putting style, the contents and tone of Blast also reflect their disdain for pretty much everyone. For example, in Blast, the Vorticists declare themselves against both the rich, whom they call “bores without a single exception” as well as the poor, whom they disparage as “detestable animals.” They also, “curse abysmal inexcusable middle-class” (Stock, 2013).

Individualism and the cult of artistic genius

Perhaps the only exception to the “blasts,” “curses,” and “expletives” that the Vorticists launched throughout their manifesto was the lone, artistic genius. The Vorticists believed that social conventions — as learned through mores, etiquette, and the education system — tainted the artist’s individuality and thus, his genius, which is expressed through his primitive impulses. For instance, the Vorticist manifesto proclaims,

The only way Humanity can help artists is to remain Independent and work unconsciously. WE NEED THE UNCONSCIOUSNESS OF HUMANITY — their stupidity, animalism and dreams. (Lewis, Blast, 1914)

The masculine and the machine

For the Vorticists, a person’s true artistic genius lies beneath the social conditioning they associate with the status quo. This comes through in the primitive, unconscious, and blunt impulses of man. For them, the artistic genius is always masculine for this reason, as Lewis detested femininity and family life as he closely associated them with the bourgeois, the sentimental, and the plebeian. Interestingly, the Vorticists also appropriated the energy and dynamism of the modern machine as a manifestation of the vortex concept because it represented the kind of strength, speed, and motion that they associated with the pure artistic impulse. In his play Enemy of the Stars (1914), which first appeared in Blast, Lewis makes such allusions to the machinist world as,

Throats iron eternities, drinking heavy radiance, limbs towers of blatant light, the stars poised, immensely distant, with their metal sides, pantheistic machines. (Lewis, 1914, [2020])

Wyndham Lewis, edited by Alan Munton

Throats iron eternities, drinking heavy radiance, limbs towers of blatant light, the stars poised, immensely distant, with their metal sides, pantheistic machines. (Lewis, 1914, [2020])

Violence, purity, and corruption

Finally, the Vorticists were preoccupied with preserving the purity of the individual artistic genius and intent on viewing society at large as a corrupting force against him. They write in a violent and aggressive tone and are preoccupied with imagery that reflects this. In the Vorticist manifesto, for example, Lewis proclaims that,

Blast sets out to be an avenue for all those vivid and violent ideas that could reach the Public in no other way. (Lewis, quoted by Meyers in The Enemy, 2021)

Moreover, in Blast, Pound provocatively asserts that violent destruction is the way to wipe clean the corrupting forces of society, by saying that “war is a great remedy. In the individual it kills arrogance, self-esteem, pride” (cited in Stock, 2013). The Vorticists remain cynical about the moral vacuousness of society as they conceive it, and, therefore, promote its outright destruction as a form of cleansing within the pages of Blast.

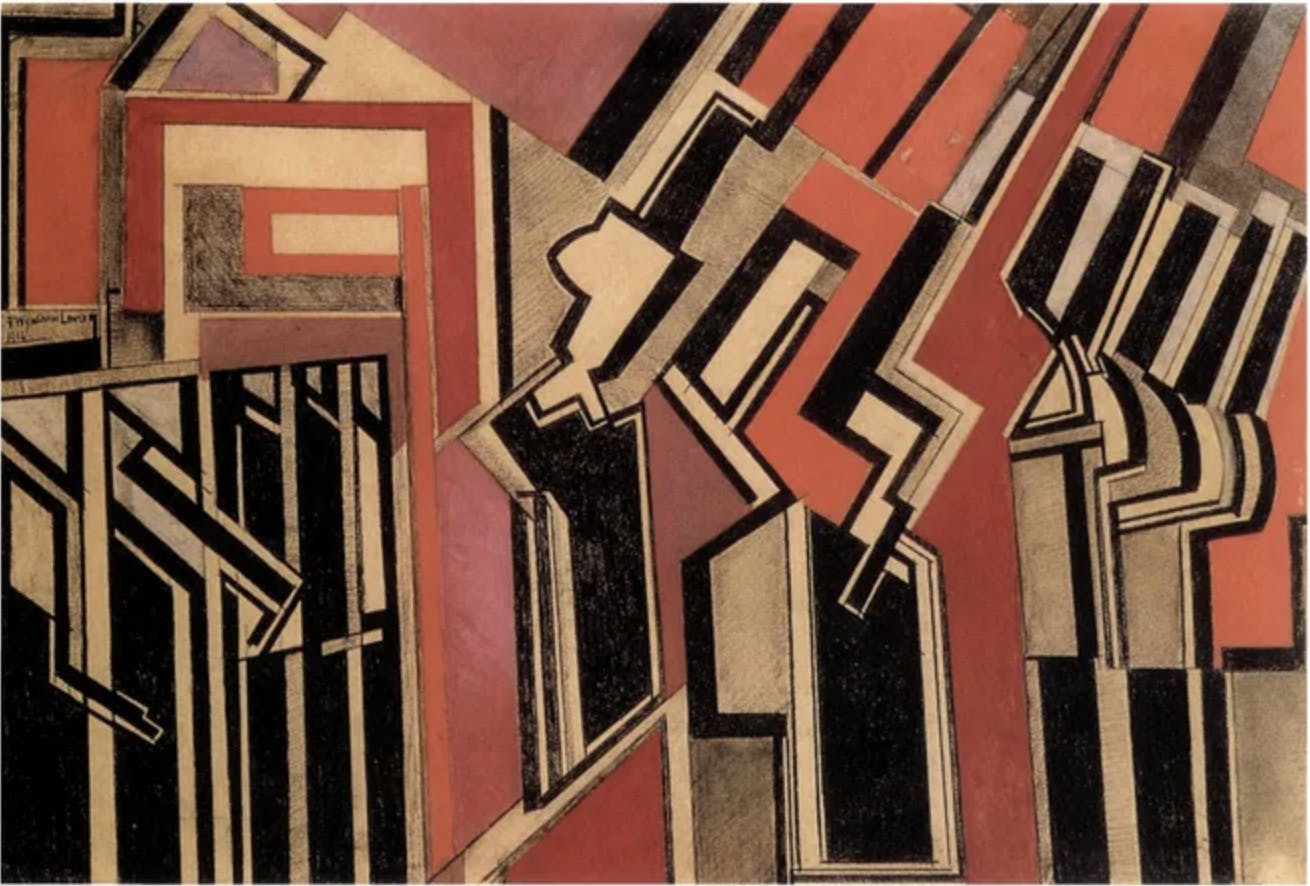

Vorticist visual aesthetics

The aesthetics of Vorticism reflected the artist’s shared conceptions and expressions of their central image: the vortex. Blending both written and visual formats, Blast’s pages are filled with poetry and drawings centered on these principles of dynamism and motion. Vorticist visual arts were characterized by strong lines, geometric patterns, and images that invoked a sense of fragmentation and mechanization associated with the modern era.

“Wyndham Lewis, Red Duet, 1914, chalk and gouache on paper, 385 x 560 mm (15¼ x 22 in)” (Blast: Vorticism, 1914–1918, 2018)

The paintings of Wyndham Lewis as well as the angular, primitivist sculptures of artists Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Jacob Epstein were of particular centrality in shaping the Vorticist visual aesthetic. Yet, in more recent times, the women painters of the Vorticists such as Helen Saunders and Jessica Dismorr, have gained more recognition.

Vorticism’s reception & legacy

Reception

Vorticism was quite unpopular at the time, and very few copies of Blast were ever sold. Its unapproachable style and tone succeeded in being off-putting to those it was condemning in its pages, which included just about everyone from the bourgeois cultural elites to regular people, and even to other modernists. What’s more is that Lewis even had a hard time getting a number of contributors to Blast to officially associate themselves with the movement (Edwards, 2018). Moreover, Blast only published two editions, as the onset of WWI swept away any remnants of a coherent movement of artists and writers dedicated to the cause, and the majority of the Vorticist paintings were destroyed.

Still, as Richard Cork highlights,

[The Vorticists] managed to forge an identifiably national art … from a radical international context; they created a highly abstract vocabulary which retained manifold and enriching links with the form-language of the visible world; and they demonstrated in a taut, bracing and often exhilarating manner how … to fully take account of even the most terrifying aspects of twentieth-century life. (Cork, quoted by Meyers in The Enemy, 2021)

Indeed, despite its ephemerality and poor reception, Vorticism has still been a prolific force of modernist avant-gardism.

Enduring influences

Despite the fact that by most counts Vorticism was neither popular nor long-lasting in its own right, its legacy lives on in a few key ways. As Edwards argues,

[...] Blast itself, and the work produced by the Vorticists and those associated more or less closely with them, already constituted the initiation of a real avant garde in England. ( 2018).

Furthermore, much of Vorticism’s striking artistic and literary contributions still maintain an avant-garde flavor even more than 100 years later, rather than becoming more assimilated into the mainstream over time.

In addition to helping to inaugurate the avant-garde in England, Vorticism is credited with influencing a number of other avant-garde groups including Surrealism, Cubism, Expressionism, Dadaism, and abstract art. In recent years, the legacy of Vorticism has been explored in a number of notable art exhibitions including, “The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World,” at the Tate Modern in 2011, which was curated by art historian, Mark Antliff. Even if short lived, challenging, and not very accessible to the wider public, Vorticism marked a high point in the modernist movement that played a role in shifting the artistic and literary landscape for those that came after.

Further reading on Perlego

Antliff, M. (2007). Avant-Garde Fascism. Duke University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1465617/avantgarde-fascism-the-mobilization-of-myth-art-and-culture-in-france-19091939-pdf

Ayers, D. (2008). Modernism: A Short Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2764482/modernism-a-short-introduction-pdf

Gasiorek, et al. (2016). Wyndham Lewis and the Cultures of Modernity. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1632321/wyndham-lewis-and-the-cultures-of-modernity-pdf

Griffin, G. (2003). Difference In View: Women And Modernism. Taylor & Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1620182/difference-in-view-women-and-modernism-pdf

Jameson. F. (2016). The Modernist Papers. Verso. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/731196/the-modernist-papers-pdf

Vorticism FAQs

What is Vorticism in simple terms?

What is Vorticism in simple terms?

What is an example of Vorticism?

What is an example of Vorticism?

Who are the figures associated with Vorticism?

Who are the figures associated with Vorticism?

Bibliography

Edwards, P. (2018) Blast: Vorticism, 1914–1918. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1500046/blast-vorticism-19141918-pdf

Kramer, H. (2017) The Age of the Avant-garde. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1579331/the-age-of-the-avantgarde-19561972-pdf

Lewis, W. (1914) Blast. John Lane Company.

Lewis, W., Munton A. (ed.) (2020) Collected Poems and Plays. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2011660/wyndham-lewis-collected-poems-and-plays-pdf

Meyers, J. (2021) The Enemy. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2949364/the-enemy-a-biography-of-wyndham-lewis-pdf

Stock, N. (2013) The Life of Ezra Pound. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1678533/the-life-of-ezra-pound-pdf

Walz, R. (2013) Modernism. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1547428/modernism-pdf

Williams, R. (2020) Politics of Modernism. Verso. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3785678/politics-of-modernism-against-the-new-conformists-pdf

MA, Sociology (Freie Universität Berlin)

Lily Cichanowicz has a master's degree in Sociology from Freie Universität Berlin and a dual bachelor's degree from Cornell University in Sociology and International Development. Her research interests include political economy, labor, and social movements. Her master's thesis focused on the labor shortages in the food service industry following the Covid-19 pandemic.