- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Art and finance coalesce in the elite world of fine art collecting and investing. Investors and collectors can't protect and profit from their collections without grappling with a range of complex issues like risk, insurance, restoration, and conservation. They require intimate knowledge not only of art but also of finance. Clare McAndrew and a highly qualified team of contributors explain the most difficult financial matters facing art investors. Key topics include:

- Appraisal and valuation

- Art as loan collateral

- Securitization and taxation

- Investing in art funds

- Insurance

- The black-market art trade

Clare McAndrew has a PhD in economics and is the author of The Art Economy. She is considered a leading expert on the economics of art ownership.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fine Art and High Finance by Clare McAndrew in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Investments & Securities. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

An Introduction to Art and Finance

Dr. Clare McAndrew

The international art market is estimated to have turned over more than $60 billion in total sales of fine and decorative art and antiques in 2008, one of its highest-ever recorded totals. By sheer size alone, therefore, it is easy to see why it has sparked the interest of the mainstream investment community: the art trade is big business. It is also a truly global business, with sales of art taking place literally all around the world. Although geographically concentrated to some degree in terms of value in the two main centers of London and New York, virtually every country has an art market of some form.

For the purposes of understanding how this unique global market functions, it is important at the outset to clarify the art that will be considered. The chapters that follow consider both fine and decorative art (and, in places, antiques). These artworks were generally made for creative, decorative purposes or what some might refer to as “art for art’s sake”—the motivation for their creation and continued existence is essentially the artworks themselves (as opposed to more utilitarian “craft” works or more commercial and functional works of design). These works are collected, bought, and sold for a range of reasons, including aesthetic, historical, and financial.

Fine art includes the basic categories of paintings, sculpture, works on paper (including watercolors, drawings, and photographs), and tapestries. Decorative art covers furniture and decorations (in glass, wood, stone, metal, and ceramic), couture (costumes and jewelry), ephemera, and textiles. Definitions of antiques vary widely, but in this context the term refers mainly to items that are at least fifty to one hundred years old and are collected or desirable due to their rarity, condition, historical significance, or some other unique feature. Some of the larger dealers and art auction houses sell a variety of other “collectibles,” such as wine, coins, vintage cars, sports memorabilia, stamps, and toys. Although some of these items have many characteristics in common with works of art (and although art is itself a collectible), these goods often function on markets with different characteristics from the art market and are therefore best classified separately.

Despite its sizable turnover and international dimensions, the art market, up until fairly recently, has tended to be the focus of wealthy collectors and a relatively elitist group of art experts, with closely guarded knowledge and trading practices. Over the last decade, however, art has sparked the interest of the mainstream financial community as an investment asset class. Although some of the older art elites might claim to be somewhat uncomfortable with their blatant partnership, the worlds of art and finance have been closely linked for hundreds of years throughout the history of the art market. In recent years, as some of its opacity has begun to slowly lift, the modern art market has begun to evolve into an international financial trading platform in which specialized assets are exchanged by a widening group of investors, both individual and institutional, with many as interested in their financial benefits as in their aesthetic beauty or historical importance.

The Art Market: A Brief Modern History

A brief review of the modern history of the art market shows some of the factors that have shaped the art trade over time, largely (but not solely) due to the drift of economic power and wealth. Although the geographical epicenters of the international art trade have shifted through history, many of the old foundations are still apparent in the modern art market and contribute to its current flow and infrastructure.

Many historians mark the period following the Industrial Revolution, when art began to become more widely traded and the primary role of the patron was diminished, as the impetus of today’s modern art market. The birth of a new middle class in this era brought a new breed of collector to the art market who, for the first time, had both the time and the money to collect art.

During the eighteenth century, Britain and France emerged as the major global art markets and the key centers for trade, while countries such as Italy acted as primary source markets for wealthy European buyers. The British art market expanded during the second half of the eighteenth century, and the first major auction houses also began to appear such as Christie’s and Sotheby’s that still dominate the market today. During the 1800s, a variety of factors caused a geographic shift in the art market from London to Paris, particularly for the avant-garde, and Paris enjoyed the position as cultural capital for a period. However, the French reign was relatively short-lived, as wider economic and political events, a Wall Street market crash, and a massive devaluation of the French franc caused many dealers to go out of business and shifted power toward the U.S. and U.K. markets, where economic and buyer strength rested.

American buyers began to dominate the global art trade during the recessionary bear markets of the 1920s and 1930s. As noted by one of the leading London art dealers of this period, Joseph Duveen, “Europe had plenty of art and America had plenty of money,” and Duveen and his colleagues on both sides of the Atlantic capitalized on this circumstance, creating highly successful art dealerships particularly from the trade in Old Master paintings.

Paris had a temporary revival as a world art center during the 1950s and 1960s; however, over the 1960s, New York and London dominated, largely due to their established bases of wealth and economic power and to the introduction of a new system of taxes on art sales and other regulatory deterrents in France. During these years, the major auction houses of Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Parke-Bernet in New York thrived and began to attract a wider interest from wealthy collectors and investors, particularly for Modern art sales. In previous decades, buyers at auctions tended to be a small number of highly informed dealers who understood the market, had expertise in particular specialties, and purchased at lower prices in order to resell to collectors. During the 1960s and particularly in the recessionary early 1970s, however, art began to be promoted as a hedge against rampant and escalating inflation, and auctions began to attract an increasing number of “retail” clients. To respond to this trend, some of the “supergalleries” emerged, with global outlets in various cities throughout the world to accommodate an expanding buyer base. Although sales in many sectors were eventually affected by wider economic events like the oil crisis in 1973, art was being increasingly bought by investors and speculators as well as by collectors.

Throughout the 1970s, the distinctions between the two international art capitals also became more defined: New York took premier position for the trade in sectors such as Contemporary art, Impressionists, Post-Impressionists and others, while London was the international center for Old Masters, English and French eighteen-century art, and Asian antiques.

During the global prosperity of the 1980s, all of the established art centers flourished, and it became hugely popular and often very profitable to buy art. The global art market entered a boom period from about 1987, marked by the emergence of record prices at auction for works of art, especially in the Modern and Contemporary sectors, and especially in New York. At the height of the boom in 1990, van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet was sold for a record $82.5 million at Christie’s in New York by Japanese paper magnate Ryoei Saito, which is still one of the most expensive paintings ever sold in real terms.1

As art prices soared and returns and dividends on stock markets started to contract, speculators added fuel to an art market that was already becoming overheated. The art market bubble at the end of the 1980s was particularly exacerbated by strong Japanese buying, mainly in the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist sectors. This demand-induced bubble was largely fueled by tax avoidance and the inflation-backed buildup of wealth in property. Added to this, the yen had also appreciated significantly against the dollar without a concurrent drop in exports, leaving the Japanese awash with money. Surplus cash, combined with a lack of discrimination on the part of new purchasers, caused prices to rise sharply, often with huge sums paid for mediocre works. That art boom ended abruptly in 1990 as a sharp rise in interest rates by the Bank of Japan forced many speculative collectors to go under, often because of a collapse of liquidity caused by unrelated investments. Many collections still remain in bank vaults, previously secured as collateral against corporate loans that failed during the Japanese recession that followed.

From this international low in 1990 and 1991, the art market has steadily advanced in terms of volume and value. Over the last eighteen years, several sectors of the market have gained significant ground—such as Impressionist, Modern, and Contemporary—while others have been on slower trajectories. Although most international markets showed a slight dip in 2002-2003, from that point until the end of 2008 the market as a whole, and many of the categories within it, have been on rapidly advancing paths of growth in terms of both individual prices and overall aggregate value. A particularly noticeable trend in recent years has been that fine art has risen in value both in absolute terms and in relation to decorative art.

The Current Structure of the Art Market

The twenty-first century has witnessed astonishing growth in the international market for works of art. Values peaked in 2007 after several years of rapid growth, with the global art market estimated to have reached a high of over $65 billion, including both dealer and auction sales of fine and decorative art and antiques. This represented its highest ever total, and the amount had more than doubled in a period of just five years.

After a relatively poor year in 2003, the market had a steady path of growth over the following four years, with growth per annum in its value averaging 28 percent since 2003. The fine art market was a key driver of growth during this period, with prices and values rising steadily, as this sector gained significant ground over decorative art. Certain categories within the fine art sector experienced phenomenal growth in value, including Contemporary, Impressionist, and Modern art. Contemporary art in particular showed exceptional growth and became the largest category of art by value at the major auction houses in 2007.

After seven consecutive years of rapid price inflation, the art market experienced a change in its aggregate trend in late 2008, as the trickle-down effects of the global financial crisis and economic recession were felt in some sectors. Just as it had been the leader in its expansive phase, the fine art market was also the key driver of the contraction of the art market during 2008, with sales at auction in this sector dropping by over 10 percent from 2007 values. Total global sales of fine and decorative art and antiques were estimated to have dropped to about $60 billion2 by the end of 2008, with the Contemporary sector in particular showing a marked decline in average prices and values at the end of that year.

Although the most notable decline in sales values occurred in the art sales in the fall of 2008, global prices for fine art at auction contracted as early as the first quarter of the year (with aggregate prices in first-quarter 2008 down 7.5 percent from fourth-quarter 2007). A notable feature of auction sales at the end of 2008 was a high rate of buy-ins or unsold works at auction, reflecting a degree of wariness on the part of buyers compared with previous years. The average buy-in rate at fine art auctions in October 2008 was approximately 44 percent, more than twice the rate of the same month in 2007.3

Although the contraction in prices during 2008 represented the sharpest fall in the market since its previous “bust” in 1991, it is important to remember that the decline in aggregates is due in part to the fact that 2007 was such a boom year, and the levels of sales in 2008 and 2009 are still markedly above any years preceding 2006. For example, the turnover of the global market in 2006 was estimated at $54 billion, still some $6 billion lower than 2008. Contractions in average prices also mask important information in the market, as they do not reveal which sectors of the market were doing well or poorly, or what quality of works were on the market in this year versus previous years. In early 2009, aggregate sale rates and prices improved in some sectors, including the main spring sales of Contemporary art at auction.4 However, again, it is impossible to determine from this (without drilling down into these sales in more detail) if the market bounced back or if in fact simply better quality works were sold.

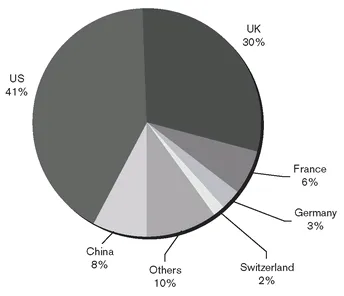

The art market remains dominated by the two major art markets of the United States and the United Kingdom, which together accounted for over two-thirds of the global trade by value. The United States remains the largest market by far, with a share of over 40 percent .5

Although the position of these two dominant markets has not changed significantly in the last decade, their combined share has slipped a few percentage points in recent years largely due to the rise of China. Figure 1.1 shows that China is now the third largest global art market with a market share of 8 percent, and has substantially overtaken previously leading markets such as France and Germany. This trend has continued since 2006, when China made significant inroads in the global art landscape for the first time, pushing Germany from its fourth position. The rise of China as a global player in the art market highlights one of the biggest transformations in the market over the last five years, namely, the emergence of a number of new and thriving art markets and art centers around the world, such as China, India, Russia, and the Middle East.

The presence of buyers from these newer “emerging” economies in the international art market has substantially increased demand, particularly in the Contemporary sector, and has been driven primarily by economic factors, specifically by the increasing wealth of their populations. While economic growth in some of the older Western economies has slowed in recent years, many of the emerging markets have shown strong and steady growth. New wealthy buyers that have emerged over the last few years from those countries have shown distinct preferences for Contemporary art, often originating from their own countries, causing a boom in sectors such as Chinese Contemporary painting.

From 2003 until the end of 2007, the aggregate art auction market grew by 311 percent, and the Contemporary art market grew by 851 percent. Although this growth has been a global phenomenon, with Contemporary markets such as the United States advancing 543 percent over the period, the growth in the newer global players has been staggering, with the Chinese Contemporary art market rising over 11,000 percent. These rapidly rising prices and expanding sales have been supported by an increase in the number of newly wealthy Chinese who for the first time have the purchasing power to participate actively in the market, alongside their Western counterparts.6 Although, as noted above, the Contemporary sector was one of the worst hit within the art market in the fallout of the economic crisis of 2007 and 2008, this expanded base of global buyers undoubtedly saved the market to some degree from a 1991/1992-style meltdown.

FIGURE 1.1 Global Art Market Share, 2007

Source: Arts Economics (2008)

It is important to note that due to the opacity of the market and the lack of data on private dealer sales, measuring the market is not easy. Auction data combined with dealer polling have formed the cornerstones of the quantification of the art trade and the basis of the numbers above. At the outset, however, it is important to remember that there is essentially no such thing as “the art market.” The market is by no means a single homogenous entity, but rather a conglomeration of distinct markets, each developing at its own individual rate. The “art market” is in fact the name given to the aggregation of many independently moving and unique submarkets that are defined by artists and genres and often behave in significantly different ways.

Each underlying segment of the market has its own artists, experts, academics, dedicated collectors, specialist dealers, sometimes auction houses, and importantly their own independently moving price trajectories and inherent risks. This is fundamental to understanding investment in the market. Art can be a good investment because it trades on more than one hundred submarkets, many of which have very different returns and risks as well as their own definable patterns of trade. Any assessment of how the aggregated art market is faring in terms of prices, returns, or risk therefore can only be used as a very general guide to assess broad trends, and is often not useful in making specific investment decisions.

Another important structural feature of the art market is that it operates on a two-tier system made up of the primary and secondary markets, with the latter dominating the trade in terms of value and volume. The primary market is where artists first sell new work directly to collectors and dealers and on an agency basis, typically through dealers and brokers. Some living artists also make initial sales directly through auction houses, but this is generally limited to very well known artists. Outlets for trade in the primary art market therefore tend to be artists’ studios, art fairs or festivals, and galleries or art dealers, and the price points are often lower than in the secondary market. Sellers in the market are made up of new and unknown artists as well as more established Contemporary artists. Buyers in this tier of the market are faced with a lack of full and perfect information and often subject to high transaction costs in time, effort, and dealers’ commissions. Some segments of this market are mad...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- About the Editor

- Acknowledgements

- About the Contributors

- Chapter 1 - An Introduction to Art and Finance

- Chapter 2 - Art Appraisals, Prices, and Valuations

- Chapter 3 - Art Price Indices

- Chapter 4 - Art Risk

- Chapter 5 - Art Banking

- Chapter 6 - Art Funds

- Chapter 7 - The Government and the Art Trade

- Chapter 8 - Insurance and the Art Market

- Chapter 9 - Art and Taxation in the United States

- Chapter 10 - Art and Taxation in the United Kingdom and Beyond

- Chapter 11 - Art Conservation and Restoration

- Chapter 12 - The Illegal Art Trade

- Index

- ABOUT BLOOMBERG