- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

History and Clinical Examination at a Glance

About this book

Every medical student must be able to take an accurate history and perform a physical examination. This third edition of History and Clinical Examination at a Glance provides a concise, highly illustrated companion to help you develop these vital skills as you practice on the wards. Building on an overview of the patient/doctor relationship and basic enquiry, the text supports learning either by system or presentation of common conditions, with step-by-step and evidence-based information to support clinical examination and help you formulate a sound differential diagnosis.

History and Clinical Examination at a Glance features:

- Succinct text and full colour illustrations, including many brand new clinical photographs

- A new section on the development of communication skills, which explains how to communicate in different circumstances, and with different groups of people

- A self-assessment framework which can be used individually, by tutors, or in group practice to prepare for OSCEs

History and Clinical Examination at a Glance is the perfect guide for medical, health science students, and junior doctors, as an ideal resource for clinical attachments, last-minute revision, or whenever you need a refresher.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access History and Clinical Examination at a Glance by Jonathan Gleadle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Internal Medicine & Diagnosis. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

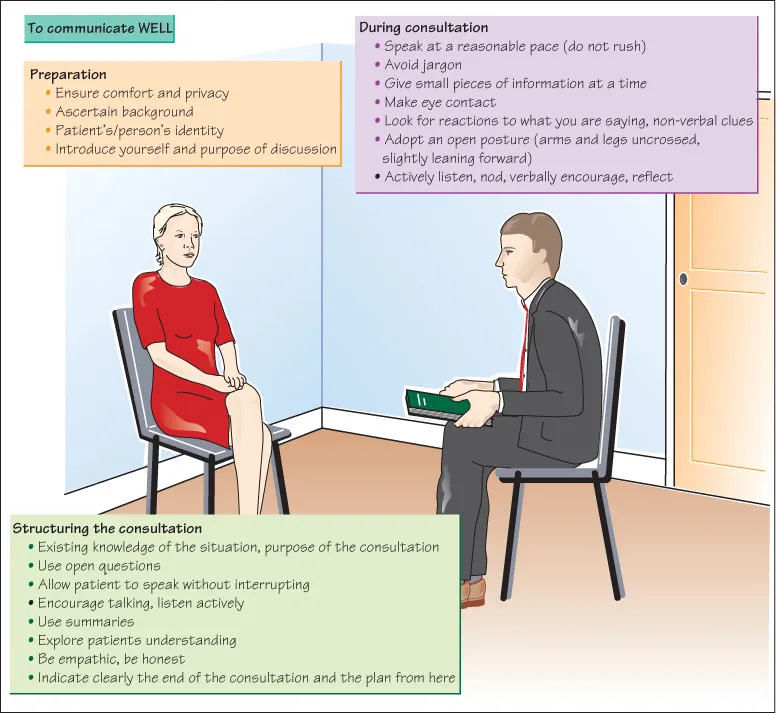

Fundamental communication skills

Good communication with patients, relatives and colleagues is central and essential for good patient care. Excellent communication is what characterizes excellent doctors above all else. Doctors who are good communicators will have patients who are more satisfied with their care, more likely to follow advice and less anxious about their problems and are preferred by patients. Poor communication is the major cause of medical errors, diagnostic errors and patient complaints.

Excellent communicators are better placed to achieve correct diagnoses, form strong relationships with patients and colleagues, impart difficult news, involve patients in important decisions, detect distress and convey emotion.

Confidence in communication is not the same as having excellent communication skills.

Observing and copying other doctors is not necessarily a good route to acquiring good communication skills. Whilst observing doctor–patient interactions, think:

- What are the good communication skills being shown here?

- What is the patient thinking?

- What is the doctor trying to convey?

- What did the patient understand?

- What did the patient feel?

- What did the patient misunderstand? Why?

- What did the doctor misunderstand? Why?

- What would I do differently as the doctor?

- What questions could the doctor have asked differently?

- What aspects of the consultation did I feel uncomfortable about? Why?

- What would have improved the consultation? More time? More introduction? Less questioning? Fewer closed questions?

It is important to practise communication skills with real patients, colleagues and simulated patients. Get feedback. Review video recording of your interviews. Reflect on things you feel you do well, things you do poorly and things you find difficult. Throughout your medical career continue to reassess your communication skills and performance and obtain expert feedback.

Consider what could be barriers to good communication, e.g. language fluency, hearing difficulties, visual difficulties, haste, interruptions.

Open and Closed Questions

Use open questions as much as possible and keep them simple and short:

- How are you?

- How can I help?

- Tell me what’s troubling you?

- Tell me about the cough.

Avoid

Leading or closed questions:

- The referral letter says you coughed up blood; was it bright red?

Avoid

Complex questions:

- e.g. You’ve had a cough, chest pain and weight loss for months now?

Avoid

Medical jargon:

- Tell me about this haemoptysis.

Further questions can be directed to generate further detail:

- e.g. You mentioned a cough … ?

- Tell me more.

Listen

One of the most important features of excellent communication is listening. Give the patient time to respond and to talk, don’t interrupt, prompt verbally (e.g. ‘Tell me more’; ‘Go on’) and non-verbally (e.g. nodding). Let the patient drive the direction of the consultation. Pay attention, maintain eye contact and focus on the patient. Don’t be (or appear to be) overly distracted by taking notes or typing on a keyboard. Look for non-verbal cues. Encourage continuation by repeating back of phrases, e.g. ‘You said you were worried about the cough … ?’ or even more detailed recapping of what they have said. ‘You’ve told me that this cough has worried you because it’s been going on for months now, is that right?’

Don’t fill pauses/silences.

Be prepared to repeat and rephrase questions.

You may need to direct the interview by asking the patient to focus on particular issues (but don’t interrupt and don’t ask too many questions):

- e.g. Tell me more about coughing up blood.

- I’d like to talk more about the weight loss in a minute but could you tell me more about the chest pain … ?

Summarize

Towards the end of the consultation you may wish to summarize what the patient has said. ‘Let me check I’ve understood completely what you’ve said’; ‘Have I got that right?’; ‘What have I missed?’

It can form part of ending a consultation. Indicate clearly that the consultation is coming to an end. Indicate clearly what is going to happen next and what the patient should do, e.g. ‘So you now need to take this form to the X-ray department and make an appointment to discuss the results with me in 2 weeks’ OR

‘I’m now going to write up my notes, discuss things with my Consultant and come back and talk to you in 30 minutes to discuss a plan for managing your illness.’

2

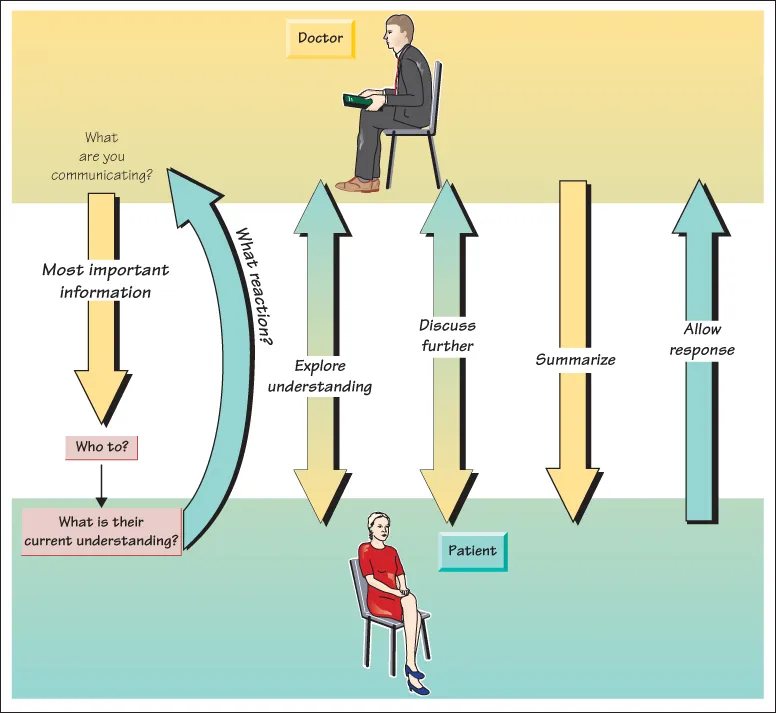

Communicating information

There are a large number of different circumstances in which doctors may wish to give information. This might include how to start a new medication and possible side effects, the risks of an operation, the discovery of a physical abnormality, the results of a blood test or biopsy or advice about a healthier lifestyle. Good communication of such information will result i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 Fundamental communication skills

- 2 Communicating information

- 3 Communicating bad news

- 4 Communicating with relatives

- 5 Cultural differences

- 6 Exploring sensitive issues

- 7 History and examination in clinical exams

- 8 Relationship with patient

- 9 History of presenting complaint

- 10 Past medical history, drugs and allergies

- 11 Family and social history

- 12 Functional enquiry

- 13 Is the patient ill?

- 14 Principles of examination

- 15 The cardiovascular system

- 16 The respiratory system

- 17 The gastrointestinal system

- 18 The male genitourinary system

- 19 Gynaecological history and examination

- 20 Breast examination

- 21 Obstetric history and examination

- 22 The nervous system

- 23 The musculoskeletal system

- 24 Skin

- 25 The visual system

- 26 Examination of the ears, nose, mouth, throat, thyroid and neck

- 27 Examination of urine

- 28 The psychiatric assessment

- 29 Examination of the legs

- 30 General examination

- 31 Presenting a history and examination

- 32 Chest pain

- 33 Abdominal pain

- 34 Headache

- 35 Vomiting, diarrhoea and change in bowel habit

- 36 Gastrointestinal haemorrhage

- 37 Indigestion and dysphagia

- 38 Weight loss

- 39 Fatigue

- 40 The unconscious patient

- 41 The intensive care unit patient

- 42 Back pain

- 43 Hypertension

- 44 Swollen legs

- 45 Jaundice

- 46 Postoperative fever

- 47 Suspected meningitis

- 48 Anaemia

- 49 Lymphadenopathy

- 50 Cough

- 51 Confusion

- 52 Lump

- 53 Breast lump

- 54 Palpitations/arrhythmias

- 55 Joint problems

- 56 Red eye

- 57 Dizziness

- 58 Breathlessness

- 59 Dysuria and haematuria

- 60 Attempted suicide

- 61 Immunosuppressed patients

- 62 Diagnosing death

- 63 Shock

- 64 Trauma

- 65 Alcohol-related problems

- 66 Collapse

- 67 Myocardial infarction and angina

- 68 Hypovolaemia

- 69 Heart failure

- 70 Mitral stenosis

- 71 Mitral regurgitation

- 72 Aortic stenosis

- 73 Aortic regurgitation

- 74 Tricuspid regurgitation

- 75 Pulmonary stenosis

- 76 Congenital heart disease

- 77 Aortic dissection

- 78 Aortic aneurysm

- 79 Infective endocarditis

- 80 Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis

- 81 Prosthetic cardiac valves

- 82 Peripheral vascular disease

- 83 Diabetes mellitus

- 84 Hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism

- 85 Addison’s disease and Cushing’s syndrome

- 86 Hypopituitarism

- 87 Acromegaly

- 88 Renal failure

- 89 Polycystic kidney disease

- 90 Nephrotic syndrome

- 91 Urinary symptoms

- 92 Testicular lumps

- 93 Chronic liver disease

- 94 Inflammatory bowel disease

- 95 Splenomegaly/hepatosplenomegaly

- 96 Acute abdomen

- 97 Pancreatitis

- 98 Abdominal mass

- 99 Appendicitis

- 100 Asthma

- 101 Pneumonia

- 102 Pleural effusion

- 103 Fibrosing alveolitis, bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis and sarcoidosis

- 104 Carcinoma of the lung

- 105 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- 106 Pneumothorax

- 107 Tuberculosis

- 108 Stroke

- 109 Parkinson’s disease

- 110 Motor neurone disease

- 111 Multiple sclerosis

- 112 Peripheral neuropathy

- 113 Carpal tunnel syndrome

- 114 Myotonic dystrophy and muscular dystrophy

- 115 Myasthenia gravis

- 116 Cerebellar disorders

- 117 Dementia

- 118 Rheumatoid arthritis

- 119 Osteoarthritis and osteoporosis

- 120 Gout and Paget’s disease

- 121 Ankylosing spondylitis

- 122 Systemic lupus erythematosus and vasculitis

- 123 Malignant disease

- 124 Scleroderma

- 125 AIDS and HIV

- Appendix: A self-assessment framework of communication skills in history and examination

- Index

- End User License Agreement