- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

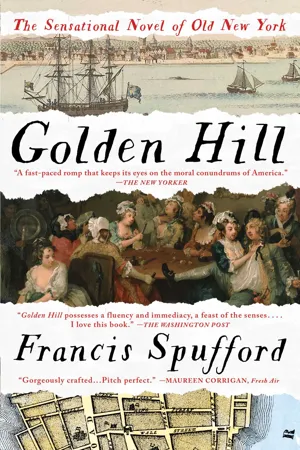

A Wall Street Journal Top Ten Fiction Book of the Year * A Washington Post Notable Fiction Book of the Year * A Seattle Times Favorite Book of the Year * An NPR Best Book of the Year * A Kirkus Reviews Best Historical Fiction Book of the Year * A Library Journal Top Historical Fiction Book of the Year * Winner of the Costa First Novel Award, the RSL Ondaatje Prize, and the Desmond Elliott Prize * Winner of the New York City Book Award

“Gorgeously crafted…Spufford’s sprawling recreation here is pitch perfect.” —Maureen Corrigan, Fresh Air

“A fast-paced romp that keeps its eyes on the moral conundrums of America.” —The New Yorker

“Delirious storytelling backfilled with this much intelligence is a rare and happy sight.” —The New York Times

“Golden Hill possesses a fluency and immediacy, a feast of the senses…I love this book.” —The Washington Post

The spectacular first novel from acclaimed nonfiction author Francis Spufford follows the adventures of a mysterious young man in mid-18th-century Manhattan, thirty years before the American Revolution.

New York, a small town on the tip of Manhattan island, 1746. One rainy evening in November, a handsome young stranger fresh off the boat arrives at a countinghouse door on Golden Hill Street: this is Mr. Smith, amiable, charming, yet strangely determined to keep suspicion shimmering. For in his pocket, he has what seems to be an order for a thousand pounds, a huge sum, and he won’t explain why, or where he comes from, or what he is planning to do in the colonies that requires so much money. Should the New York merchants trust him? Should they risk their credit and refuse to pay? Should they befriend him, seduce him, arrest him; maybe even kill him?

Rich in language and historical perception, yet compulsively readable, Golden Hill is “a remarkable achievement—remarkable, especially, in its intelligent re-creation of the early years of what was to become America’s greatest city” (The Wall Street Journal). Spufford paints an irresistible picture of a New York provokingly different from its later metropolitan self, but already entirely a place where a young man with a fast tongue can invent himself afresh, fall in love—and find a world of trouble. Golden Hill is “immensely pleasurable…Read it for Spufford’s brilliant storytelling, pitch-perfect ear for dialogue, and gift for re-creating a vanished time” (Newsday).

“Gorgeously crafted…Spufford’s sprawling recreation here is pitch perfect.” —Maureen Corrigan, Fresh Air

“A fast-paced romp that keeps its eyes on the moral conundrums of America.” —The New Yorker

“Delirious storytelling backfilled with this much intelligence is a rare and happy sight.” —The New York Times

“Golden Hill possesses a fluency and immediacy, a feast of the senses…I love this book.” —The Washington Post

The spectacular first novel from acclaimed nonfiction author Francis Spufford follows the adventures of a mysterious young man in mid-18th-century Manhattan, thirty years before the American Revolution.

New York, a small town on the tip of Manhattan island, 1746. One rainy evening in November, a handsome young stranger fresh off the boat arrives at a countinghouse door on Golden Hill Street: this is Mr. Smith, amiable, charming, yet strangely determined to keep suspicion shimmering. For in his pocket, he has what seems to be an order for a thousand pounds, a huge sum, and he won’t explain why, or where he comes from, or what he is planning to do in the colonies that requires so much money. Should the New York merchants trust him? Should they risk their credit and refuse to pay? Should they befriend him, seduce him, arrest him; maybe even kill him?

Rich in language and historical perception, yet compulsively readable, Golden Hill is “a remarkable achievement—remarkable, especially, in its intelligent re-creation of the early years of what was to become America’s greatest city” (The Wall Street Journal). Spufford paints an irresistible picture of a New York provokingly different from its later metropolitan self, but already entirely a place where a young man with a fast tongue can invent himself afresh, fall in love—and find a world of trouble. Golden Hill is “immensely pleasurable…Read it for Spufford’s brilliant storytelling, pitch-perfect ear for dialogue, and gift for re-creating a vanished time” (Newsday).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Golden Hill by Francis Spufford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

All Hallows

November 1st

20 Geo. II

1746

I

The brig Henrietta having made Sandy Hook a little before the dinner hour—and having passed the Narrows about three o’clock—and then crawling to and fro, in a series of tacks infinitesimal enough to rival the calculus, across the grey sheet of the harbour of New-York—until it seemed to Mr. Smith, dancing from foot to foot upon deck, that the small mound of the city waiting there would hover ahead in the November gloom in perpetuity, never growing closer, to the smirk of Greek Zeno—and the day being advanced to dusk by the time Henrietta at last lay anchored off Tietjes Slip, with the veritable gables of the city’s veritable houses divided from him only by one hundred foot of water—and the dusk moreover being as cold and damp and dim as November can afford, as if all the world were a quarto of grey paper dampened by drizzle until in danger of crumbling imminently to pap:—all this being true, the master of the brig pressed upon him the virtue of sleeping this one further night aboard, and pursuing his shore business in the morning. (He meaning by the offer to signal his esteem, having found Mr. Smith a pleasant companion during the slow weeks of the crossing.) But Smith would not have it. Smith, bowing and smiling, desired nothing but to be rowed to the dock. Smith, indeed, when once he had his shoes flat on the cobbles, took off at such speed despite the gambolling of his land-legs that he far out-paced the sailor dispatched to carry his trunk—and must double back for it, and seizing it hoist it instanter on his own shoulder—and gallop on, skidding over fish-guts and turnip leaves and cats’ entrails, and the other effluvium of the port—asking for direction here, asking again there—so that he appeared most nearly as a type of smiling whirlwind when he shouldered open the door—just as it was about to be bolted for the evening—of the counting-house of the firm of Lovell & Company, on Golden Hill Street, and laid down his burden while the prentices were lighting the lamps, and the clock on the wall showed one minute to five, and demanded, very civilly, speech that moment with Mr. Lovell himself.

“I’m Lovell,” said the merchant, rising from his place by the fire. His qualities in brief, to meet the needs of a first encounter: fifty years old; a spare body but a pouched and lumpish face, as if Nature had set to work upon the clay with knuckles; shrewd and anxious eyes; brown small-clothes; a bob-wig yellowed by tobacco smoke. “Help ye?”

“Good day,” said Mr. Smith, “for I am certain it is a good day, never mind the rain and the wind. And the darkness. You’ll forgive the dizziness of the traveller, sir. I have the honour to present a bill drawn upon you by your London correspondents, Messrs. Banyard and Hythe. And request the favour of its swift acceptance.”

“Could it not have waited for the morrow?” said Lovell. “Our hours for public business are over. Come back and replenish your purse at nine o’clock. Though for any amount over ten pound sterling I’ll ask you to wait out the week, cash money being scarce.”

“Ah,” said Mr. Smith. “It is for a greater amount. A far greater. And I am come to you now, hot-foot from the cold sea, salt still on me, dirty as a dog fresh from a duck-pond, not for payment, but to do you the courtesy of long notice.”

And he handed across a portfolio, which being opened revealed a paper cover clearly sealed in black wax with a B and an H. Lovell cracked it, his eyebrows already half-raised. He read, and they rose further.

“Lord love us,” he said. “This is a bill for a thousand pound.”

“Yes, sir,” said Mr. Smith. “A thousand pounds sterling; or as it says there, one thousand seven hundred and thirty-eight pounds, fifteen shillings and fourpence, New-York money. May I sit down?”

Lovell ignored him. “Jem,” he said, “fetch a lantern closer.”

The clerk brought one of the fresh-lit candles in its chimney, and Lovell held the page up close to the hot glass; so close that Smith made a start as if to snatch it away, which Lovell reproved with an out-thrust arm; but he did not scorch the paper, only tilted it where the flame shone through and showed in paler lines the watermark of a mermaid.

“Paper’s right,” said the clerk.

“The hand too,” said Lovell. “Benjamin Banyard’s own, I’d say.”

“Yes,” said Mr. Smith, “though his name was Barnaby Banyard when he sat in his office in Mincing Lane and wrote the bill for me. Come, now, gentlemen; do you think I found this on a street-corner?”

Lovell surveyed him, clothes and hands and visage and speech, such as he had heard of it, and found nothing there that closed the question.

“You might ha’ done,” he said, “for all I know. For I don’t know you. What is this thing? And who are you?”

“What it seems to be. What I seem to be. A paper worth a thousand pounds; and a traveller who owns it.”

“Or a paper fit to wipe my arse, and a lying rogue. Ye’ll have to do better than that. I’ve done business with Banyard’s for twenty year, and settled with ’em for twenty year with bills on Kingston from my sugar traffic. Never this; never paper sent all on a sudden this side the water, asking money paid for the whole season’s account, almost, without a word, or a warning, or a by-your-leave. I’ll ask again: who are you? What’s your business?”

“Well: in general, Mr. Lovell, buying and selling. Going up and down in the world. Seeing what may turn to advantage; for which my thousand pounds may be requisite. But more specifically, Mr. Lovell: the kind I choose not to share. The confidential kind.”

“You impudent pup, flirting your mangled scripture at me! Speak plain, or your precious paper goes in the fire.”

“You won’t do that,” said Smith.

“Oh, won’t I? You jumped enough a moment gone when I had it nigh the lamp. Speak, or it burns.”

“And your good name with it. Mr. Lovell, this is the plain kernel of the matter: I asked at the Exchange for London merchants in good standing, joined to solid traders here, and your name rose up with Banyard’s, as an honourable pair, and they wrote the bill.”

“They never did before.”

“They have done now. And assured me you were good for it. Which I was glad to hear, for I paid cash down.”

“Cash down,” repeated Lovell, flatly. He read out: “ ‘At sixty days’ sight, pay this our second bill to Mr. Richard Smith, for value received . . .’ You say you paid in coin, then?”

“I did.”

“Of your own, or of another’s? As agent, or principal? To settle a score or to write a new one? To lay out in investments, or to piss away on furbelows and sateen weskits?”

“Just in coin, sir. Which spoke for itself, eloquently.”

“You not finding it convenient, no doubt, to move so great a weight of gold across the ocean.”

“Exactly.”

“Or else hoping to find a booby on the other side as’d turn paper to gold for the asking.”

“I never heard that New-Yorkers were so easy to impose on,” said Mr. Smith.

“So we aren’t, sir,” said Lovell, “so we aren’t.” He drummed his fingers. “Especially when one won’t take the straight way to clear off the suspicion we may be gulled. —You’ll excuse my manner. I speak as I find, usually; but I don’t know how I find you, I don’t know how to take you, and you study to keep me uncertain, which I don’t see as a kindness, or as especial candid, I must say, in a strip of a boy who comes demanding payment of an awk’ard-sized fortune, on no surety.”

“On all the ordinary surety of a right bill,” protested Smith.

“There you go,” Lovell said. “Smiling again. Commerce is trust, sir. Commerce is need and need together, sir. Commerce is putting a hand in answer into a hand out-stretched; but when I call you a rogue, you don’t flare up, as is the natural answer at the mere accusation, and call me a rogue for doubting.”

“No,” returned Smith cheerfully. “For you’re right, of course. You don’t know me; and suspicion must be your wisest course, when I may be equally a gilded sprig of the bon ton, or a flash cully working the inkhorn lay.”

Lovell blinked. Smith’s voice had darkened to a rookery croak, and there was no telling if he was putting on or taking off a mask.

“There’s the lovely power of being a stranger,” Smith went on, as pleasant as before. “I may as well have been born again when I stepped ashore. You’ve a new man before you, new-made. I’ve no history here, and no character: and what I am is all in what I will be. But the bill, sir, is a true one. How may I set your mind at rest?”

“You’ve the oddest notion in the world of reassurance, if you’re in earnest,” said Lovell, staring. “You could tell me why I’ve had no letter, to cushion this surprise. I’d have expected an explanation, a warning.”

“Perhaps I out-paced it.”

“Perhaps. But I believe I’ll keep my counsel till I see more than perhaps.”

“Of course,” said Mr. Smith. “Nothing more natural, when I may be a rascal.”

“Again, you make mighty free with that possibility,” Lovell said.

“I only name the difficulty you’re under. Would you trust me more if we pretended some other thing were at issue?”

“I might,” said Lovell. “I might well. An honest man would surely labour to keep off the taint of such a thing. You seem to be inviting it, Mr. Smith. Yet I can’t be so casual, can I? My name’s my credit. Do you know what will happen if I accept your bill, for your secret business, your closed-mouth business, your smiling business, your confidential business? And you discount it with some good neighbour of mine, to lay your hands on the money as fast as may be, as I’ve no doubt you mean to? Then there’ll be sixty-day paper with my name upon’t, going round and round the island, playing the devil with my credit just at the turn of the season, in no kind of confidence at all. All will know it; all will know I’m to be dunned for a thousand pound, and wonder should they try to mulct me first.”

“But I won’t discount it.”

“What?”

“I won’t discount it. I can wait. There is no hurry. I have no pressing need for funds; sixty days’ sight, it says, and sixty days will suit me perfectly. Keep the bill; keep it under your eye; save it from wandering.”

“If I accept it, you mean.”

“Yes. If you accept it.”

“And if I don’t?”

“Well, if you protest it, I shall make this the shortest landing in the colonies that ever was heard of. I shall walk back along the quay, and when the Henrietta is loaded, I shall ship home, and lodge my claim for damages with Banyard’s.”

“I don’t protest it,” said Lovell, slowly. “Neither yet do I accept it. It says here, our second bill, and I’ve not seen hide or hair of first nor third. What ships d’ye say they’re bound on?”

“Sansom’s Venture and Antelope,” said Mr. Smith.

“Well,” said Lovell, “here’s what we’ll do. We’ll wait and we’ll see; and if the others of the set turn up, why then I’ll say I accepted the bill today, and you shall have your sixty days, and if you’re lucky you may be paid by quarter-day; and if they don’t appear, why then you’re the rascal you tease at being, and I’ll have you before the justices for personation. What do you say?”

“It’s irregular,” said Mr. Smith, “but something should be allowed for teasing. Very well: done.”

“Done,” echoed Lovell. “Jem, note and date the document, will you? And add a memorandum of this agreement; and make another note that we’re to write to Banyard’s on our own account, by the first vessel, asking explanations. And then let’s have it in the strongbox, to show in evidence, as I suspect, for the assizes. Now, sir, I believe I’ll bid you—” Lovell checked himself, for Smith was feeling through the pockets of his coat. “Was there something else?” he asked heavily.

“Yes,” said Smith, bringing forth a purse. “I’m told I should break my guineas to smaller change. Could you furnish me the value of these in pieces convenient for the city?”

Lovell looked at the four golden heads of the King glittering in Smith’s palm.

“Are they brass?” said one of the prentices, grinning.

“No, they’re not brass,” said Lovell. “Use your eyes, and not your mouth. Why ever—?” he said to Smith. “Never mind. Never mind. Yes, I believe we can oblige you. Jem, get out the pennyweights, and check these.”

“Full weight,” the clerk reported.

“Thought so,” said Lovell. “I am learning your humours, Mr. Smith. Well, now, let’s see. We don’t get much London gold, the flow being, as you might say, all the other way; it’s moidores, and half-joes, mostly, when the yellow lady shows her face. So I believe I could offer you a hundred and eighty per centum on face, in New-York money. Which, for four guineas, would come to—”

“One hundred and fifty one shillings, twopence-halfpenny.”

“You’re a calculator, are you? A sharp reckoner. Now I’m afraid you can have only a little of it in coin; the reason being, as I said when first we began, that little coin is current at the present.” Lovell opened a box with a key from his fob chain and dredged up silver—worn silver, silver knocked and clatter’d in the battles of circulation—which he built into a little stack in front of Smith. “A Mexica dollar, which we pass at eight-and-fourpence. A piece of four, half that. A couple of Portugee cruzeiros, three shillings New-York. A quarter-guilder. Two kreutzers, Lemberg. One kreutzer, Danish. Five sous. And a Moresco piece we can’t read, but it weighs at fourteen pennyweight, sterling, so we’ll call it two-and-six, New-York. Twenty-one and fourpence, total. Leaving a hundred and twenty-nine, tenpence-halfpenny to find in paper.”

Lovell accordingly began to count out a pile of creased and folded slips next to the silver, some printed black and some printed red and some brown, like the despoiled pages of a prayerbook, only of varying shapes and sizes; some limp and torn; some leathery with grease; some marked only with dirty letterpress and others bearing coats-of-arms, whales spouting, shooting stars, feathers, leaves, savages; all of which he laid down with the rapidity of a card-dealer, licking his fingers for the better passage of it all.

“Wait a minute,” said Mr. Smith. “What’s this?”

“You don’t know our money, sir?” said the clerk. “They didn’t tell you we use notes, specie being so scarce, this side?”

“No,” said Smith.

The pile grew.

“Fourpence Connecticut, eightpence Rhode Island,” murmured Lovell. “Two shilling Rhode Island, eighteenpence Jersey, one shilling Jersey, eighteenpence Philadelphia, one shilling Maryland . . .” He had reached the bottom of the box. “Excuse me, Mr. Smith; for the rest we’re going to have to step upstairs to my bureau. We don’t commonly have the ca...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Chapter 1: All Hallows, November 1st, 20 Geo. II, 1746

- Chapter 2: Pope Day, November 5th, 20 Geo. II, 1746

- Chapter 3: His Majesty’s Birthday, November 10th, 20 Geo. II, 1746

- Chapter 4: A Letter to the Reverend Pompilius Smith, New-York, 1st December 1746

- Chapter 5: Sinterklaasavond (St. Nicholas’ Eve), December 5th, 20 Geo. II, 1746

- Chapter 6: A Letter to Richard Smith, Esqr., Mrs. Lee’s, The Broad Way, Golden Hill, Monday night

- Chapter 7: O Sapientia, December 16th, 20 Geo. II, 1746

- Chapter 8: Quarter-Day, December 25th, 20 Geo. II, 1746

- Chapter 9: A Letter to Gregory Lovell, Esqr., Golden Hill Street, City of New-York: by the ship Crown of Heligoland

- Chapter 10: August 1814

- Reading Group Guide

- Author’s Note

- ‘Light Perpetual’ Teaser

- About the Author

- Copyright