![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Revolt of the Munsee

The Destruction of New Amsterdam and the Creation of New York, 1629–1664

AMANDA HURON AND RAYMOND PETTIT

New York City was born out of the ashes of revolt.

Early in the morning of September 15, 1655, a fleet of sixty-four canoes filled with nearly two thousand Munsee warriors set off from the shores of what is now New Jersey, heading east across the Hudson River toward the island of Manhattan. The Munsee and other Lenape bands had for decades been engaged in a low-grade war with Dutch settlers, and relations were once again reaching a breaking point. When the Munsee landed on the beaches of Manhattan that late summer day, they began an all-out assault against the Dutch. Over the course of three days, the Munsee burned farms, destroyed buildings and cattle, and killed settlers. Known as the Peach War, it was the most terrifying attack during the period of Dutch rule, paving the way for the English seizure of the territory just a few years later in 1664. Without the Munsee revolt, New York might never have become New York.

The Dutch, the Munsee, and Manhattan

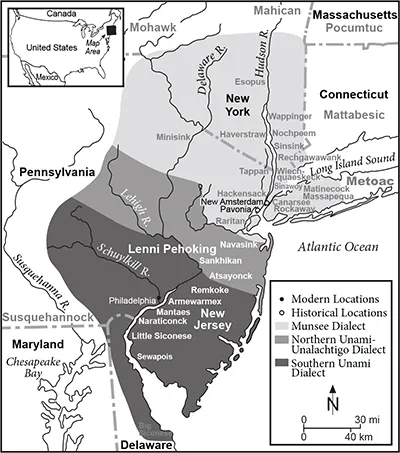

At the time of European contact, the Munsee were loosely affiliated indigenous groups living in a region from roughly what is now New Jersey to Connecticut—an area called Lenapehoking, the Land of the Lenape. “Munsee” refers to a language group, a dialect of the larger Delaware language, but it is also used to refer to many of the “bands” of Lenape. “Lenape” itself is a Munsee word meaning “People” (or “Men”).1 The Munsee of the Manhattan area were respected by surrounding groups (many of them also Munsee)—the Raritans, Hackensacks, Tappans, Wiechquasgecks, Sinawoys (or Siwanoys), Matinecocks, Rockaways, and others—with whom they sometimes formed alliances and sometimes skirmished. While not politically centralized, something like these groups’ sovereignty over Lenapehoking was well established when the first European contact was made by explorer Giovanni de Verrazano (or Verrazzano) on behalf of the French in 1524.

When the Munsee set out to attack Manhattan on that September morning in 1655, they had their sights set on New Amsterdam, the small Dutch town at the very southern tip of the island that was the capital of the larger Dutch territory of New Netherland, itself established as part of the Dutch effort to create a vigorous overseas mercantile empire.* The Dutch first visited the area in 1609 under Henry Hudson, an English explorer hired for the voyage. Hudson had been contracted by the Dutch East India Company to find a northwest passage to the Pacific, but he stumbled upon Manhattan and its surrounds instead. The Dutch laid claim to the land Hudson found and called it New Netherland. The land seemed unusually abundant in resources, and its estuarine ecosystem was especially rich. Indeed, the whole area seemed rich in potential for profit. As an entry from Hudson’s ship’s log noted, Manhattan “is as pleasant a land as one can tread upon, very abundant in all kinds of timber suitable for ship-building, and for making large casks. The people have copper pipes, from which I inferred that copper must exist there; and iron likewise according to the testimony of the natives, who, however, do not understand preparing it for use.”2

Native American Geography at the Time of Dutch Colonization.

Cartography: Joe Stoll, Syracuse University Cartography Lab and Map Shop, redrawn from a map by Nikator.

New Netherland was not originally a proper colony but a Dutch “sphere of interest.” The Dutch claimed to possess legal authority only onboard their boats—the “law of the ship”—while the Munsee were sovereign on the land. Dutch crews wintered in New Netherland, but not with an eye to settling. There was thus no fixed Dutch governmental administration planted on the land and charged with overseeing a colony. In the first years of the Dutch claim, New Netherland comprised a heterogeneous mass of sovereign Munsee bands near the mouth of the Hudson, each of which had to be negotiated and traded with by individual naval representatives of Dutch power. There was no standard policy of objectives for Dutch and Munsee interactions, other than to generate a profit in the trade of beaver furs. Neither the Dutch nor the Munsee dominated, and legal and commercial relations and boundaries were quite fluid. Early New Netherland was a classic “middle ground” of European and Native American contact.3

The fur trade that dominated Dutch commercial activity in New Netherland in the early years did not require a permanent European population. Furs were collected by Munsee and then traded at various points along the coast for European goods, hence New Netherland’s status as merely a sphere of interest. But the States-General—the Dutch parliamentary chamber—as well as some Dutch mercantile interests thought New Netherland needed to be populated to act as a bulwark against encroaching English colonists. The States-General therefore granted the Dutch West India Company (a quasi-commercial, quasi-governmental organization) a monopoly over New Netherland trade in 1621 and encouraged the establishment of a permanent colony. Some in the company directorate argued against settling colonists, fearing that fur-trade profits were insufficient to support a permanent colony. Some even turned the bulwark argument on its head, contending that if a hostile takeover by English settlers or others was possible, then a lack of colonial investment was no bad thing. The colonizing faction countered that a Dutch colony could be self-sufficient in two or three years and would not unduly burden the company. A compromise was effected between the two factions in 1624. The company would encourage colonists to settle in New Netherland, but it would maintain a monopoly on commerce, and all colonists would technically be company employees.

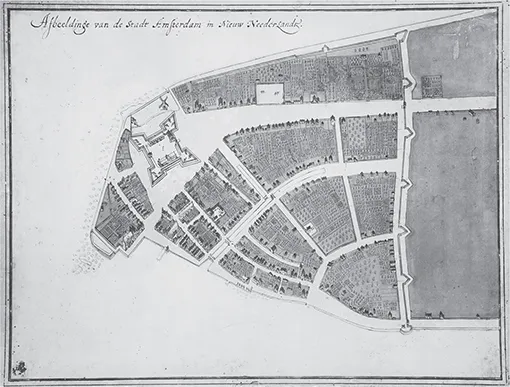

A ca. 1665 copy of Jacques Courtelyou’s 1660 map of New Amsterdam, Afbeeldinge can de Stadt Amsterdam in Nieuw Neederland.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs, New York Public Library.

As a result, the Dutch needed to set up a local government in New Netherland. The company ordered its colonial director, Peter Minuit, to purchase land from the Munsee. He bought Manhattan in January 1626.* As Domine Michaëlius informed company heads in Amsterdam, “This island is the key and principal stronghold of the country, and needs to be settled first.”4 With the purchase came a new administrative policy. No longer did the Dutch understand the Munsee to be completely sovereign peoples. Instead they were ambiguously independent Dutch subjects: the Dutch made it clear that the Munsee were still largely autonomous, but they claimed authority to regulate Dutch and Munsee trade. Whereas previously the Dutch claimed sovereignty only aboard their own boats, now the Dutch extended this sovereignty onto land and made moves to regulate Dutch-Munsee interactions even beyond trade. The Munsee maintained their independent status and rights, but those were now contingent on Dutch consent. And as Minuit’s purchase had made plain, Munsee land could now be bought and sold.

Claiming control is not the same as exercising it. At the very southern tip of Manhattan, the Dutch West India Company quickly established Fort Amsterdam and New Amsterdam as the center of Dutch administration, but outside the fort and the town’s walled enclosures it was hard for the Dutch to enforce what they now saw as their exclusive right to the land. After they sold the island to Minuit, Munsee bands continued to live and hunt on Manhattan well into the 1630s.

Nieu Amsterdam, date unknown. The figures in the foreground were stock characters in Dutch engravings of the early colonial era.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs, New York Public Library.

Low rates of European immigration to New Amsterdam and New Netherland forced the West India Company to change its settlement policy in 1629, opening the colony to nonemployees under a patroonship system. Under this system, the company made land grants (meaning the right to negotiate a purchase from the Munsee) to anyone willing to sponsor and settle fifty individuals in New Netherland. Such “privatization of colonization” may have brought settlers to the colony, but it also lessened governmental supervision.5 Dutch administrators in New Amsterdam viewed both sets of rural subjects—Munsee and Dutch patrooners—suspiciously, because, away from New Amsterdam, they tended to intermix and because, distant from the central market of New Amsterdam, much of their trade went untaxed. As the colonial secretary, Cornelius van Tienhoven, saw it, these remote settlements “produced altogether too much familiarity with the Indians . . . [rural Dutch colonists] not being satisfied with taking them into their houses in the customary manner, but attracting them by extraordinary attention, such as admitting them to table, laying napkins before them, presenting wine to them and more of that kind of thing.”6 Such unruliness undermined the arguments that New Netherland would serve as an effective bulwark against the English.

Colonial Administration, Munsee-Dutch Interdependence, and Munsee Subjugation

Back in the home country, Dutch elites viewed New Netherland distrustfully, its viability increasingly suspect. The colony seemed to be marked by high rates of alcohol consumption and low rates of Sabbath observance. As the first Dutch minister sent to the colony wrote of the settlers in a 1628 letter home, “The people for the most part are rather rough and unrestrained.”7 When Willem Kieft, the colony’s fifth director general, arrived in New Amsterdam in 1638, he found rotting ships, two of the company’s three windmills broken, a corrupt colonial administration, and the company’s five farms untenanted, their land having been “thrown into the commons.”8 Kieft set about attempting to restore discipline by implementing new rules and threatening lawbreakers with penalties and fines. In 1643, for instance, the council of New Amsterdam outlawed the sale of alcohol to Native peoples, concerned by the violence they thought accompanied Munsee drinking. But settlers who lived in outlying parts of the colony, farther from New Amsterdam, continued to trade secretly with Natives in order to avoid paying taxes to the colonial administration. Because guns fetched such high prices, settlers also traded them to Natives, even though Kieft had strictly forbidden such activity. It was only “in the neighborhood of Manhattan, where a more rigid police was maintained,” wrote one early historian, that “the supply of arms [to Natives] was prevented.”9

European market demands soon began to shape the daily lives of the Munsee. As contact between the Munsee and the Dutch increased, the Munsee became dependent not only on European guns and alcohol but also on goods like duffel cloth (a heavy woolen cloth that the Munsee came to prefer to skins for clothing), sewing needles, cooking pots, and more. The Munsee therefore had increasing incentive to trade with the Dutch, while the Dutch desire for beaver furs and land made them eager to trade with the Munsee. But unfortunately for the Munsee, they were quickly losing access to the beaver trade. Beavers had been hunted nearly to extinction in areas closest to colonial trading posts, leaving the fur trade to powerful rivals to the north and south. In the upper Hudson River valley and farther west in present-day New York State, Mohawks and Mahicans had easier access to beavers, and the Susquehannocks similarly dominated the hunting and trapping regions to the southwest in present-day New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

With reduced access to beaver, many Munsee turned to wampum production as a way to trade for the European goods on which they had increasingly come to rely. Wampum, small tubular beads made from marine shells such as clams and quahogs, had long served as sacred goods for Native peoples. The Europeans, minimally interested in the social complexities of wampum, understood it as mere currency. Dutch money was in short supply in the colony, so the Dutch incorporated wampum into their economic system, using it to trade for furs, land, and other goods. In New Amsterdam, settlers used wampum for all kinds of transactions, including paying for mortgages and ferry rides and for making tithes to the church. Wampum became the common currency of the North American colonies, with Dutch, English, and many indigenous groups using it. For many Munsee bands, wampum production and continued Dutch demand for it became a primary means for securing sustenance. This pushed the Munsee into a dependent role in the colonial economy, opening an opportunity for the Dutch under Kieft to use their dominant position to deepen Munsee colonial subjugation in New Netherland. The Dutch began to replace mere claims to colonial control with an active exercise of it.

Beginning in 1639, Kieft imposed taxes on the Munsee living in and around the New Netherland colony, demanding payment in fathoms (six feet) of wampum. The tax was necessary, Kieft argued, to recompense the Dutch for their protection of the Munsee against their Native enemies. But the Munsee resisted payment of the tax, or tribute, primarily because they did not feel adequately protected by the Dutch. According to one interpretation, however, the Munsee were upset by taxation for another reason: taxation cemented Munsee status as subjects of the Dutch.10

Kieft’s War

The question of tribute appears to be a primary cause of the violence that broke out between Munsee and Dutch in 1640—what came to be known as Kieft’s War. That year, a group of Raritans who lived on the mainland west of Staten Island threatened a Dutch ship that had come to trade with them and probably also to exact tribute. Later, when a number of hogs were killed on Staten Island, the Dutch blamed the Raritans.* Dutch soldiers then attacked the Raritans to exact vengeance, killing several individuals and destroying property, even though the soldiers had been ordered only to cut down the Raritans’ corn and to arrest the alleged offenders. In response, a year later, Raritans attacked Staten Island, killing four Dutch farmers. Kieft induced other bands, themselves eager to maintain good relations with the Dutch, to attack the Raritans.

The roiling conflict boiled over in 1641 when a man from the Munsee band Weckquaesgeek killed a Dutch settler, Claes Smits,† to avenge the murder of his uncle during the construction of Fort Amsterdam.11 Smits had run a public house on Manhattan (outside New Amsterdam) frequented by both Dutch and Munsee. Kieft attempted to use Smits’s murder to mobilize Dutch settlers against their Munsee neighbors, but he was largely unsuccessful, despite increased tensions.

Meanwhile, most Munsee were still feeling pressure from rival tribes in the area, and two years later, in 1643, bands of Weckquaesgeeks and Tappans found themselves fleeing toward the coast from conflict with Mahican enemies to the north. They took refuge near Dutch settlements in Pavonia, across the river from New Amsterdam in present-day New Jersey, and also near a fort at Corlear’s Hook, on Manhattan, just north of New Amsterdam. Kieft took this opportunity to order an attack o...