![]()

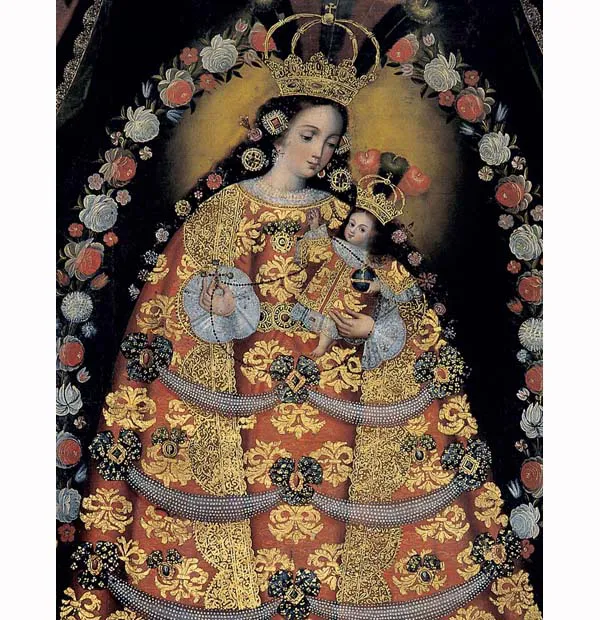

Plate 1.1 Unknown artist of the Cuzco school, Our Lady of the Rosary of Pomata (detail from Plate 1.25).

Chapter 1

From Iberia to the Americas: Hispanic art of the colonial era

Piers Baker-Bates

Introduction

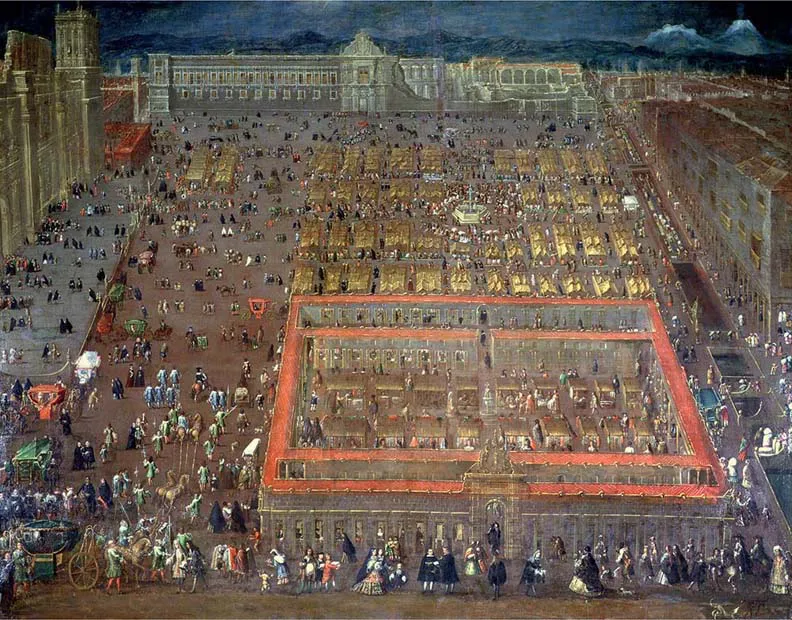

A painting by the Mexican artist Cristóbal de Villalpando depicts the central square of Mexico City, the Plaza Mayor, as it appeared at the height of Spanish colonial rule when the city was the capital of the viceroyalty of New Spain (Plate 1.2). To the left of the picture, which shows the Plaza from the west, can be seen the (still unfinished) façade of the vast cathedral of the city. Opposite the cathedral is the town hall, while at the far end of the square can be seen the viceregal palace. The painting is thus bounded by the religious and civil structures of Spanish power, like the square itself, but the centre of the scene is crowded with market stalls and people. The red-roofed structure in the foreground is the Parián, which took its name from the main market area in Manila; it was built to house shops and store goods on the orders of Gaspar de la Cerda, Count of Galve, Viceroy of New Spain from 1688 to 1696. In the bottom left corner, looking out from his carriage, appears the viceroy, who commissioned the painting in 1695. No doubt intended to serve as a memento of his viceroyalty, Villalpando’s composition celebrates the ostensible peace, piety and prosperity of Mexico under Spanish rule. It also, however, provides a reminder of the precarious nature of this rule, since the right-hand side of the viceroy’s palace lies in ruins, having been destroyed by fire during an anti-Spanish riot in 1692.1 Villalpando’s painting is not just a fascinating document of Spanish colonial rule, however, but also an example of the rich and diverse art and material culture produced in the New World between the conquest in the sixteenth century and independence in the early nineteenth century. As such, it raises significant issues for the study of Latin American art of the colonial period, an area neglected by art historians until the twentieth century but now the focus of intense scholarly interest. For one thing, it is a freestanding picture in oil on canvas painted for a Spanish official, testifying to the way that this specifically European form of artistic practice was introduced into the Americas by the colonial authorities for their own purposes. Furthermore, it depicts a space of public display, one constructed to broadcast the tenets of the Roman Catholic faith and the power of the Spanish monarchy, thereby demonstrating how the Spanish deployed architecture and urbanism as a means of asserting control over their territorial possessions. At the same time, however, the semi-ruined viceregal palace reveals that the colonial authorities did not necessarily have it all their own way. The painting thus raises the question of how far Latin American art of this period might also have been shaped by local interests, including those of the indigenous people seen in the foreground.

Plate 1.2 Cristóbal de Villalpando, View of the Plaza Mayor of Mexico City, c.1695–1704, oil on canvas, 180 × 200 cm. Corsham Court,Wiltshire. Photo: © Corsham Court/Bridgeman Images.

Questions such as these have driven recent methodological debates around colonial Latin American art.2 Earlier generations of scholars typically approached this art from a Eurocentric and colonialist perspective, taking for granted Spain’s status as a cultural centre with its colonial dominions on the periphery or margins. The idea that cultural production in Latin America was necessarily derivative of and inferior to the European canon is no longer accepted, however. Current scholarship acknowledges, for example, the debt that Villalpando owes to the work of his better-known European predecessors, notably Peter Paul Rubens, but insists that he developed out of it a distinctive style of his own, seen in his large-scale religious paintings in the sacristy of Mexico City Cathedral.3 A related topic of debate is the question of whether or not stylistic terms from the history of European art could or should be applied to Latin American art. A particularly contentious term is the Baroque, which has been widely applied to architecture and sculpture as well as to the work of painters such as Villalpando.4 Using these stylistic terms to discuss Latin American art runs the risk not only of anachronism (since the term only came into use at a later date), but also of imposing models of chronological, stylistic development entirely based on the history of European art (thereby denying Latin American art its own, distinctive trajectory).

Rejecting such Eurocentric approaches, scholars have debated how Latin American art of this period should be defined and discussed as an independent entity worthy of study. Already, in the first half of the twentieth century, Latin American scholars, taking a nationalistic and anti-colonial stance, posited the existence of a mestizo style, employing the Spanish term for a person of mixed Spanish and indigenous descent. Their aim in so doing was to emphasise that, despite its use of European art forms, this art was created in the Americas, and should be regarded as neither colonial nor indigenous but rather as the product of both equally. Although many different aspects of Latin American material culture have since been characterised as mestizo, the problem with the use of this word as a stylistic term is that it evokes complex issues of ethnicity and retains unfortunate overtones of racism.5 The crucial point here is that it was historically deployed in the New World by members of a colonial elite that prided itself on its ‘pure’ Spanish blood in order to categorise people considered to be inferior to themselves in an elaborate system of racial classification (see Section 4 below). Some scholars instead prefer to use the term ‘hybrid’, but this stills leaves unresolved the question of how the indigenous contribution to Latin American art is to be identified, given that it can be hard to discern any visible trace of such a contribution in specific works of art.6

More recent scholarship, therefore, has shifted away from this relatively rigid approach to adopt a much more fluid model of cultural exchange, often termed ‘transculturation’, in which interaction between the European and the indigenous works in both directions simultaneously. This model is further nuanced by emphasising the differences between (and within) the viceroyalties into which Spain’s worldwide empire was divided. Viceroys not only governed New Spain, founded in 1535, along with the viceroyalty of Peru, founded in 1542, but also Spain’s territories in Europe, which included much of Italy and the Netherlands. From 1565, moreover, New Spain embraced not only Spain’s territories in Central and North America but also the Philippines, the two being linked by Spanish galleons sailing annually between Manila and Acapulco. The Anglophone art historian Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann has therefore propounded a viceregal model, in which the Spanish monarchy as a whole, with its territories extending across Asia as well as Europe and the Americas, constitutes a single cultural area or field.7 This model has been described as one ‘that effectively levels the implicit hierarchical relationships embedded in the center-periphery paradigm, instead inscribing the history of colonial art within the methodological perspective of a geography of art’.8

It is therefore important in reading this chapter to bear in mind that Spain’s colonial possessions do not map neatly onto the geography of modern Latin America. For one thing, New Spain covered large swathes of what is now the south-western and southern United States. The viceroyalty of Peru, moreover, extended far beyond the area covered by the present-day country of that name to include all of South America, save its southernmost tip and the Portuguese colony of Brazil. Between 1580 and 1640, Portugal was ruled by the kings of Spain, with the result that the whole of South America technically came into Spanish possession, though Brazil continued to be ruled from Lisbon using the Portuguese structures already in place. This chapter will, however, only consider art as it developed in the two Spanish viceroyalties, which became three in 1717, when the viceroyalty of New Granada was carved out of the other two in the north-west region of South America; a final viceroyalty, that of Rio de la Plata, was established further south in 1776. Brazil is excluded because, though it had a lively cultural production of its own, it remained very different in character from that of the Spanish territories. To survey the full range of Spanish colonial art would in any case be impossible within the limits of a single chapter, which therefore takes the form of four case studies.

The case studies have been selected to represent the diversity of Spanish colonial art and material culture in Latin America, with equal representation of the two original viceroyalties and examples taken from a range of different media (though with an emphasis on painting). Together, they allow for a consideration of some of the ways in which precolonial cultures as well as imported European art and culture contributed to the artistic developments of th...