![]()

1

The grammar of culture

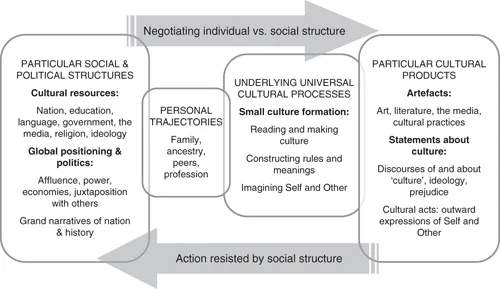

The book is driven by a grammar of culture which is represented in Figure 1.1.1 In the same way that linguistic grammar provides a structure which enables us to understand sentences, the grammar of culture provides a structure which enables us to understand intercultural events. However, it is also an invention – a map which can do no more than guide us, and which must not be mistaken for the real terrain which is too complex and deep to be mapped too accurately. Throughout, whenever mentioned for the first time in a particular discussion the items of the grammar are in bold.

FIGURE 1.1 The grammar of culture.

With the unfathomable complexity of culture in mind, the grammar comprises loose relationships which represent a conversation between its different domains. This conversation is sometimes harmonious and sometimes ridden with difficult conflict. The grammar is spread across three broad domains with arrows that indicate movement and influences between them. On either side are particular social and political structures and particular cultural products. Broadly, these domains relate to what has commonly been referred to as national, ethnic or large culture. This is however by no means straightforward, and the emphasis in the grammar is more on how the concept of large culture is constructed and imagined. It is the interaction between these particularities and the underlying universal cultural processes, in the middle of the grammar, fed by personal cultural trajectories, which will be the basis for much of the discussion throughout the book. This interaction becomes more acute because, perhaps counter-intuitively, the particular domains relate more to the large, and the universal relate more to the small and personal. The grammar is therefore a collection of diverse domains, each of which is in conversation with all of the others.

Also, there is both a potential for greater understanding and a dark side in the universal domain in that:

• It is what we all share, which enables us all to make sense of, read and interact with the particular wherever we encounter it.

• However, the universal also underpins the architecture of the prejudice that divides us.

Cultural negotiation

The arrows across the top and the bottom indicate a dialogue between the power of underlying universal cultural processes possessed by the individual and the influences of the particular cultural realities which derive from national structures. Here I am particularly interested in the potential for newcomers to be cultural innovators. However, these arrows involve all parts of the grammar and do not run from one precise part of it to another. The more promising negotiation of the individual versus structure runs left to right at the top because of the possibility that the personal helps to reduce particular structures and allow more understanding of the constructed nature of cultural products. The more restrictive curtailing of the personal by structure runs right to left along the bottom because the particular cultural products can construct essentialist forces that strengthen the power of structures. Implicit in cultural negotiation is the notion of individuals taking social action on a daily basis, which is a theme that runs throughout the grammar.

Underlying universal cultural processes

The source of the social action which is implicit throughout the grammar is in the underlying universal cultural processes in the very centre of the grammar. These processes are shared by all of us. They are common across all cultural settings. They involve skills and strategies through which everyone regardless of background participates in and negotiates their position within the cultural landscapes to which they belong. This is the basis upon which we are able to read, engage with and take part in the production of culture.

Small culture formation is the major domain where these universal processes take place. Small cultures are cultural environments, small social groupings or activities wherever there is cohesive behaviour. Examples of groupings are families and leisure and work groups. They can be as small as two people in some form of relationship. They are the basic cultural entities from which all other cultural realities grow. However, more important than being places, they are the locations of social action. Small culture formation is the process in which people form rules for how to behave. Wherever we go, we automatically either take part in or begin to build small cultures. In this sense, small culture formation happens all the time and is a basic essence of being human. Small culture formation on the go is therefore the everyday process that takes place all the time, everywhere, with whoever we meet or even think about and where we make choices about positioning and engaging or not engaging – creating, joining, leaving, conflicting with, encouraging, changing. It emphasises how transient and changing small cultures can be.

Also, in the centre of the grammar, personal trajectories comprise the individual’s travel through society, bringing histories from their ancestors and origins. Through these trajectories we are able to step out from and dialogue with the particular social and political structures that surround us and even cross into new and foreign domains. This category thus provides the everyday experience for the underlying universal cultural processes.

Particular social and political structures

On the left of the grammar, these are structures which in many ways form us and make us different from each other. They provide the backdrop for personal cultural trajectories and small culture formation on the go. The first domain is cultural resources, which is to do with how we are influenced by and draw upon particular social and political structures in our daily lives. It is here where there will be differences between us because of the particularities of how we are brought up in different societies, and it is this sort of difference that relates most closely to what many of us refer to as ‘our culture’. The way we were educated, our national institutions, the manner of our government, our media, our economy, and so on are different from nation to nation and will undoubtedly impact in the way we are as people.

These resources may be imagined as mapping precisely onto each other, for example, where a nation state corresponds largely with one religious group, one language and one economic system. This might just be possible where isolated communities have been relatively untouched by global influences. However, this synchrony is likely to be more imagined than actual, residing in our exotic idealisation of the ‘tribe’, or the lost civilisations of travellers’ tales, where we might be seduced by the idea of a single ‘culture’ where all the members share things that no one else does. Archaeology increasingly tells us that even in pre-history there was far more wide-ranging geographical exchange than we might have imagined. The relationships will therefore be more complex, and religions and languages will transcend nations or be minorities within them, even though nationalist statements may say otherwise. Economic systems may well be controlled by the nation state, but the variations of the other domains will mediate the extent to which they can be culturally defining.

I therefore prefer to label these elements as resources that we draw on, rather than constraints that confine what we do and think. Even where they are imposed upon us, we have personal resources that enable us to resist within the personal cultural trajectory category. It also needs to be remembered that many of us are between or are separated from nations.

Next, global positioning and politics concerns how we position ourselves and our society against the rest of the world. A major mechanism here is grand narratives of nation and history. These are large stories about who we are that relate to idealisations of nation and are often located in the valorisation of historical events and trajectories – wars, revolutions, stories of liberation or oppression, heroes, and so on. They are reinforced and constructed by the media, education, the statements of politicians, economists and other forces in the cultural resources domain. They are powerful resources because our opinions are not only moulded by them, but we also choose to employ them in different ways and at different times depending on circumstances. We play different ‘culture cards’ to suit how best to present ourselves in the particular circumstances that we face. An example that underpins a number of the ethnographic narratives in this book is how we label ourselves as Western or non-Western, and the values that we attach to these labels. Since the time of writing the first edition, we have seen a massive polarisation of constructions of global positioning around particular political phenomena. In the British referendum regarding leaving the European Union and its aftermath, grand narratives of ‘leave’ (Brexit) or ‘remain’ have been produced and manipulated by political parties and the media, and then splintered into the personal statements of individuals in social media and face-to-face forums. Conflicts in the Middle East and the presidency of Donald Trump have brought about both the demonisation and idealisation of nations, migration, particular religions and sects, and so on. Readers might reflect here on similar examples that pertain to their own social and political environments.

It is a major tenet of this book that almost everything intercultural is underpinned by this positioning and politics, which is very hard to see around because of the degree to which we are all inscribed by long-standing Self and Other constructions of who we are in relationship to others in our histories, education, institutions, upbringing and media representations, and that these are rooted profoundly in a world which is not politically or economically equal. A discussion of grand and personal narratives will begin in Chapter 3, and grand narratives will the major focus of Chapter 6.

The social and political structures domain raises difficult questions about the relationship between how we construct the concept of culture and reality. Here we need to think carefully about the circumstances under which we talk about ‘a culture’, and what we mean when we do this. We need then to consider how far this notion matches reality. A useful mental exercise here is to consider two countries with which we are familiar and compare how their social and political structures interact and overlap. How might the concept of ‘culture’ be thereby used in each case? What factors would act against an easy use of the concept of ‘culture’? We then need to think about how we position ourselves in relation to these two countries.

Particular cultural products

On the right of the grammar, these are the outcome of cultural activity. The first domain, artefacts, includes the ‘big-C’ cultural artefacts such as literature and the arts. They also include cultural practices, which are the day-to-day things we do which can seem strange for people coming from foreign cultural backgrounds – how we eat, wash, greet, show respect, organise our environment, and so on. These are the things which are most commonly associated with ‘our culture’ or national culture, but they also differ between small groups within a particular society and can be carried and learned across cultural locations.

The second domain, statements about culture, is perhaps the hardest of all the domains in the grammar to make sense of. It is to do with how we present ourselves and what we choose to call ‘our culture’ – how we position ourselves and how we choose to play the ‘culture card’. There is a deep and tacit politics here which means that what we choose to say and project may not actually represent how things are, but rather our dreams and aspirations about how we would like them to be, or the spin we place upon them to create the impact we wish to have on others. This is not to do with lying or deceiving, but with a genuine presentation of Self which involves a sophisticated manipulation of reality. These are the locations and products of discourses about culture that are at the core of discussions throughout the book.

How the grammar is used

The ensuing chapters do not deal with each part of the grammar one by one. Instead, the interconnection and conversation between the parts are demonstrated within the theme of each chapter. Reference to particular domains in the grammar will help break open what is going on in the narratives to expose the key forces which are at play. It is hoped that these forces will be recognisable to outsiders to the narratives and help them to read culture wherever it is by referring them back to forces they can find within their own society.

Further reference

Chapter 6 of my (2011a) book Intercultural communication and ideology describes the grammar of culture with examples. Also, throughout, there are ethnographic narratives which are analysed in a similar fashion to this book. The idea of small cultures was the starting point for developing the grammar of culture and is originally introduced in my ‘small cultures’ article (1999; 2011b).

My use of the term ‘grammar’ can be traced to the pencilled underlinings that I made as an undergraduate sociology student in C. Wright Mills’ The sociological imagination. He refers to what social scientists do to ‘imagine and build’ ideas and analysis as ‘the very grammar of the sociological imagination’ in which individuals become aware of their location in the bigger picture of society and history (1970: 234–5).

As imaginary, Mills also warns against allowing the grammar to ‘run away from its purposes’ (1970: 235). I take this to mean that it mu...