![]()

1 Small Cities, Big Challenges

Introduction

Cities have been profoundly affected by the challenges of economic restructuring and positioning in a globalizing world. They have struggled to reshape themselves physically to create new opportunities, or to rebrand themselves to create distinction and attract attention. Their strategies often draw on a limited range of “models”, taken from large industrial cities undergoing economic restructuring, such as the Baltimore waterfront development or the “Guggenheim effect” in Bilbao.

What about smaller cities that may lack the tangible resources and expertise to undertake such grandiose schemes? How can small cities put themselves on the global map? They don’t have the muscle and influence of their larger neighbours, although they struggle with the same challenges. We argue that the adoption of more strategic, holistic placemaking strategies that engage all stakeholders can be a successful alternative to copying bigger cities.

We use the Dutch city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands to illustrate how small places can grab attention and achieve growth, prosperity and social and cultural gains. This provincial city of 150,000 people put itself on the world stage with a programme of events themed on the life and works of medieval painter Hieronymus Bosch (or Jheronimus Bosch in Dutch), who was born, worked, and died in the city. For decades the city did nothing with his legacy, even though his paintings were made there. All the paintings left long ago, leaving the city with no physical Bosch legacy, and no apparent basis for building a link with him.

Eventually the 500th anniversary of Bosch’s death provided the catalyst to use this medieval genius as a brand for the city. The lack of artworks by Bosch required the city to adopt the same kind of creative spirit that his paintings embody. By developing the international Bosch Research and Conservation Project, ‘s-Hertogenbosch placed itself at the hub of an international network of cities housing his surviving works, spread across Europe and North America. The buzz created around the homecoming exhibition of Bosch artworks generated headlines around the world and a scramble for tickets that saw the museum remaining open for 124 hours in the final week. A staggering 422,000 visitors came, grabbing tenth place in the Art Newspaper’s exhibition rankings, alongside cities like Paris, London, and New York. The UK newspaper The Guardian said that the city had “achieved the impossible” by staging “one of the most important exhibitions of our century”.

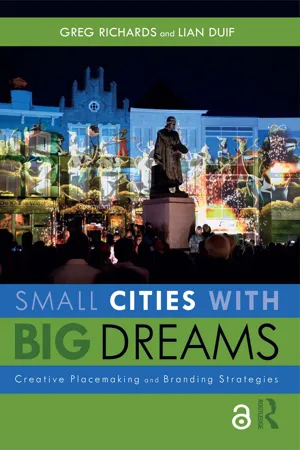

Photo 1.1 The “Hieronymus Bosch: Visions of Genius” exhibition in ‘s-Hertogenbosch (photo: Lian Duif).

This “miracle” did not happen overnight. Many people worked long and hard to make 2016 an unforgettable year. An idea that was originally met with scepticism grew into a national event, with major cultural, social, and economic effects. ‘s-Hertogenbosch put itself on the global map. But it doesn’t end there. As one participant said: “Dare to keep on dreaming big dreams. It is not over. You can create new dreams again” (Afdeling Onderzoek & Statistiek 2017: 9).

‘s-Hertogenbosch is not an isolated example. All over the globe smaller cities and places are making their mark in different ways – through events, new administrative models, community development programmes, innovative housing, new transport solutions, and other creative strategies. For example, Chemainus (British Colombia, population 4,000) was made world-famous by its outdoor gallery of murals (see Box 9.1). The formerly run-down city of Dubuque, Iowa (population 58,000) revitalized its Mississippi riverfront and now attracts well over 1,500,000 visitors a year (see Box 7.2). Hobart in Tasmania (population 200,000) has been rejuvenated by the MONA museum, as well as new events and festivals (see Box 2.1). Over one million people, including 130,000 international visitors, attended the 2016 Setouchi International Art Festival, which is held on twelve small islands in the Seto Inland Sea, Japan.

Although small places can be very successful in regenerating themselves, most attention is still focused on big cities; places with big problems, big plans, and big budgets. These are the cities that can hire starchitects and international consultants. They go for big, bold solutions, because they have little choice. Small cities may not have problems of the same scale, but they face their own challenge: how do they get noticed amongst the clamour of cities vying for attention? They can’t stage the Olympic Games, they don’t all have philanthropists to fund a museum, and they can’t afford to hire Frank Gehry or Richard Florida – so what can they do?

They can begin to play to their own strengths. They can mobilize the tangible and intangible resources they do have, link to networks, use their small scale creatively. This book highlights how small cities can become big players. As Giffinger et al. (2007: 3) note with respect to “medium-sized cities”:

Contrary to the larger metropolises, relatively little is known about efficient positioning and effective development strategies based on the endogenous potential of medium-sized cities. Therefore a recommendable approach is to draw lessons from successful development strategies applied in other medium-sized cities tackling similar challenges and issues.

We follow this advice by reviewing what successful small cities have done, and drawing lessons for others.

We also highlight the possibilities created by the new economy. In recent decades, the intangible resources of cities have become far more important in their positioning and success. Cities have a wider range of tools and materials available, as well as a broader range of potential partners. In the “collaborative economy” it is no longer necessary to own resources: you can borrow and collaboratively develop many of the tools you need. This book outlines the implications of these changes for the small city and the possibilities they present.

This chapter reviews the place of the small city in the contemporary urban field and sketches the challenges and opportunities they face. We hope the chapters that follow will help inspire a new developmental agenda for the small city.

Throwing the Spotlight on Small Cities

There has been a lot of attention paid to cities in recent decades. With 3.3 billion people now living in cities, the 21st century has been dubbed the “urban century” (Kourtit et al. 2015). Most of this attention has been focused on large cities, particularly the fast-growing mega-cities such as São Paulo, Tokyo, New York, and London. The big names in urban studies and planning also tend to focus on the biggest places. One list of “Top 20 Urban Planning Books (Of All Time)” features texts by Jane Jacobs, Lewis Mumford, Peter Hall, and Kevin Lynch, among others, dealing with cities such as New York, San Francisco, Montreal, Chicago, Los Angeles, London, Paris, New Delhi, Moscow, and Hong Kong (Planetizen 2016). Anne Power’s (2016) book Cities for a Small Continent: International Handbook of City Recovery covers cities such as Bilbao, Sheffield, Lille, Turin, and Leipzig. These are not exactly small cities, with an average population of almost 750,000.

In spite of the volume of work on large places, recent years have also seen growing academic and professional interest in smaller places. This trend became evident around 2005, with a surge in books dealing specifically with the situation of small cities. Almost all of these volumes contrasted the position of small cities with those of the metropolis. Garrett-Petts’s (2005) Small Cities Book argues that Culture (with a capital C) was equated with big city life. In subsequent studies of cities of under 100,000 people for the Small Cities Community-University Research Alliance (CURA), Garrett-Petts found that small cities tended to position themselves either as a scaled-down metropolis or as a small city with a big-town feel. Collected volumes by Bell and Jayne (2006) and Ofori-Amoah (2006) also paid specific attention to small cities and the urban experience “beyond the metropolis”. Daniels et al. (2007) produced the first Small Town Planning Handbook (now in its third edition). At the same time Baker (2007) produced a guide to destination branding for small cities. A small-cities research agenda emerged, driven at least in part by what Jayne et al. (2010: 1408) argued was “[d]issatisfaction with urban theory dominated by study of ‘the city’ defined in terms of a small number of ‘global’ cities”. This new agenda for research on small cities spawned yet more studies, with Connolly (2012) looking at the plight of industrial small cities, and Norman (2013) examining the effect of globalization, immigration, and other changes on small cities in the USA. He concluded that the influence of such factors is more nuanced in small cities than in their larger counterparts.

In 2012 Anne Lorentzen and Bas van Heur edited a volume on the Cultural Political Economy of Small Cities, arguing that smaller cities and their often distinct cultural strategies had been largely ignored. Criticizing the “metropolitan bias” of scholars such as Alan Scott and Richard Florida, they focused on culture and leisure, which they saw as key drivers of development in recent decades. Wuthnow (2013) also studied Small-Town America, through over 700 in-depth interviews, and concluded that the “smallness” of these places shapes their social networks, behaviour, and civic commitments and produces a strong sense of attachment. Walmsley and Kading (2017) also considered the plight of small cities in Canada confronting serious social issues in the post-1980s neoliberal climate. They conclude that while some cities have managed to develop inclusionary responses to external change, others have singularly failed. As well as these general reviews of the small-city condition, specific small cities have also been analysed. Trenton, New Jersey, is seen by Richman (2010) as a “lost city” in the post-industrial age. Dikeman (2016) charts Mayor Dan Brooks’s career in North College Hill, Ohio, showing how he helped to put this small city on the map. A more global view is offered by Kresl and Ietri (2016), who use data from both the USA and Europe in their analysis of Smaller Cities in a World of Competitiveness. In the contemporary urban world, they point out, one of the imperatives is competing for attention.

There is clearly more attention focused on smaller cities now, although there is still a lack of coherent analysis. In particular, there is relatively little known about the process of small-city development – how and why particular small cities succeed. To start addressing this question, we first need to look at the urban field as a whole, and the position of smaller cities within it.

The Global Urban Field

In 2014, the United Nations counted 28 mega-cities of over 10 million people, containing around 12% of the global population. However, there are many more smaller cities than large ones: around 43% of the world’s population live in cities of 300,000 inhabitants or fewer. In the European Union, approximately half of the cities have a population of between 50,000 and 100,000 inhabitants. In the year 2000, slightly more than half of the USA’s population lived in settlements with fewer than 25,000 people or in rural areas (Kotkin 2012). These places of fewer than 25,000 residents make up the vast majority of “urbanized areas” in the US. As the Atlantic City Lab (2012) notes: “Of the 3,573 urban areas in the U.S. (both urbanized areas and urban clusters), 2,706 of them are small towns” – or almost 80%.

As Horacio Capel (2009) noted, what “small” means depends on context. Studies in Europe (Laborie 1979), Latin America, and North America all have differing size categories for “small” or “medium” cities. “Small” might therefore be viewed more as a state of mind: Bell and Jayne (2006), for example, describe small cities as having limited urbanity and centrality, so that they have limited political and economic reach beyond their immediate surroundings, matched by limited aspirations, and self-identification as “small” places. Language also affects our idea of what the city is and therefore what constitutes “smallness”. For example, the English language distinguishes between a city and a town, a distinction which is often (although not always) related to size and function. But this distinction is not reflected in the use of the words ville in French or ciudad in Spanish.

Capel (2009: 7) further notes that the competitive situation of small cities has changed in recent decades:

In the current situation of generalized urbanization, the meaning of middle and small cities is changing, with respect to what happened in the past. While it could long be asserted that urban growth was a very positive fact (the larger, the better), since the 1960s, when the controversy about growth limits was raised, this perspective began to change.

These days there is more attention paid to balanced growth – an area in which small cities may have significant advantages in terms of innovation, easy access to knowledge and culture, links to areas of dynamic economic development, and above all being very agreeable places to live in (Capel 2009).

The recognition of these qualities of small cities means that the population decline that characterized many smaller cities until recently has now been reversed in many places. Smaller cities can offer a better quality of life and as a result they are often growing faster. “Many of the fastest growing cities in the world are relatively small urban settlements” (United Nations 2014). Europe has witnessed population shifts from urban to rural and from larger to smaller cities (Dijkstra et al. 2013: 347):

large cities no longer play the driving role in the second decade of modern globalization since the turn of the millennium that they did during the 1990s, the first decade of the modern globalization. Economic growth in Europe is increasingly driven by predominantly intermediate and predominantly rural regions, as well as predominantly urban regions.

In spite of the relative importance of smaller cities, according to Kresl and Ietri (2016) there has been a lack of theorization and comparative research. This means we know a lot about larger cities and their problems, but a lot less about small cities and their challenges and opportunities. There is some evidence to suggest that we cannot simply apply what we know about large cities to smaller ones. Size matters, because the growth of cities produces qualitative changes in the mixture of residents, their housing, transport, and other infrastructure, and the provision of services. Larger cities provide the density to support a level of service provision that smaller places find it hard to replicate. In the Netherlands, Meijers (2008) concluded that simply adding small places together does not provide the same level of amenities per head of the population as found in larger cities.

Small cities are therefore qualitatively di...