![]()

p.21

Part I

BRITISH SILENT CINEMA TO THE COMING OF SOUND

1895–1930

![]()

p.23

1

THE ORIGINS OF BRITISH CINEMA, 1895–1918

Bryony Dixon

Introduction

It is time to look at British silent film with new eyes. No article on it can apparently be written without alluding to its poor reputation on the international scene, but as we have arrived at a moment of change in the accessibility of historical sources, it’s time to look again. This era of film history will be studied differently from now on, with an unprecedented mass of digitized films being made available on online platforms. Having these primary sources increasingly accessible, as well as an equivalent mass of contemporary contextual material to follow, should broaden out the study of our film heritage in many ways. We will almost certainly pay more attention to non-fiction and short films, which are easier to publish online, and find it easier to make connections between films of different producing companies and countries, which will increasingly internationalize film history. From being an area of film history that has been disregarded by the mainstream, British film may finally be seen in its proper context as something worthy of notice, enjoyment and study.

Despite excellent written resources such as the major history of British cinema between 1895 and 1929 which was written by Rachael Low between 1948 and 1971 and the thorough work on the British filmography by Denis Gifford and the BFI, British silent films, with the exception of a selection of pioneer films and one or two Hitchcock titles, failed to penetrate the histories of international cinema or the programming of silent films in cinematheques and festivals. A concerted effort to remedy this situation began with the founding of the British Silent Film Festival in 1998, which aimed to screen all the available extant films and to promote research. Academic projects and publications have flourished as source materials have become gradually easier to access and major discoveries like the Mitchell and Kenyon films have gained worldwide press attention and removed some of the prejudices that had sprung up around silent film in preceding decades. Restoration, cinema and festival programming, and the expansion in broadcasting and publication on DVD, Blu-ray and online in recent years has exposed a great number of people to Britain’s silent film heritage. Recent digital developments are set to massively increase the availability of film and contextualizing records to the public.

p.24

What this opening up of the archives means is that from now on early silent film can increasingly be used, in conjunction with other historical records, to inform our view of this period of history for a broad audience. The BFI National Archive has always had a twin remit to preserve film as an art – unbelievably we are still struggling with film being properly recognized as such – and as a record as the life and customs of the British people. For many decades film as art and popular fiction entertainment has had more critical attention. As things stand, with way the Internet has developed, it is now short form and non-fiction films that are being privileged. A huge amount of this material is now coming through from all of the UK’s film archives. Early film even more so, due to the public’s natural interest in things that are older, easier-to-clear copyrights and the media’s fixation on anniversaries. Longer fiction film will follow in greater number once rights issues are resolved. There has also been a boom in live cinema (i.e. silent film with live accompaniment) and education and creative music projects using early film. It is now more surprising if a child has not seen a silent film by the time they are 16 than if they have.

So, as we are at the dawn of a new era in how our cinema can be seen and understood, let’s cast off the shackles of film historiography and our national insecurity about British cinema and look back 120 years to the dawn of another era, the birth of film.

1895 to 1901: Victorian

p.25

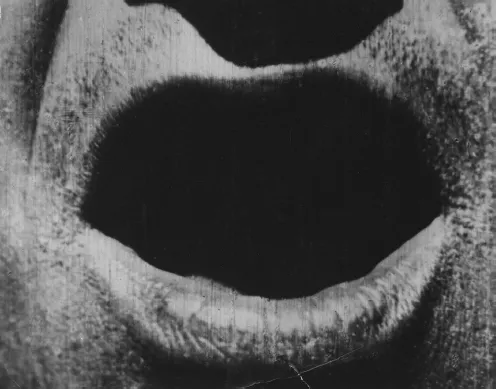

Britain has more than its fair share of the many ‘firsts’ in the birth of film and these are well documented. In fact the early years of filmmaking in this country have been written about extensively and very well. It is an international story of discovery, invention, development and improvement (as well as a lot of copying and imitation). A fascinating assortment of inventors, engineers, entertainers, entrepreneurs and scientists all contributed to the early film trade in a number of countries. Amongst these, here are a few of our homegrown pioneers: the Frenchman Louis Le Prince working in Leeds, Robert Paul, Birt Acres, W. K. L. Dickson, Charles Goodwin Norton, Walter Gibbons, Edward Turner and Frederick Lee, John Alfred Prestwich, A. C. Bromhead, Cecil Hepworth and Charles Urban, all based in London, William Friese-Greene, George Albert Smith and James Williamson on the south coast, James Bamforth, Frank Mottershaw and the Riley Brothers in Yorkshire, Mitchell and Kenyon in Blackburn, William Walker and George Greene in Scotland, Arthur Cheetham working in Wales, and touring exhibitors like Randall Williams and A. D. Thomas. There were many others too, involved in all aspects of getting the film business started. As with the birth of other major media like radio or the internet there was a flurry of chaotic super-invention. It is only a slight exaggeration to say that everything you could think of to do with film was tried in the first 10 years by these and their counterparts in other countries – all the genres: actuality, drama, comedy, news, westerns, war and crime films, romance and social problem films, adaptations of classics from Shakespeare and Dickens. All types of attractions were tried, from the aesthetic, such as Rough Sea at Dover (1896), a simple shot of waves crashing against a pier, to the cerebral and self-reflexive films like The Big Swallow (1901) taken from the point of view of a pesky cameraman who, refusing to respect the privacy of an irate tourist, is swallowed, camera, tripod and us (as it were) with him.

In the technical field too, everything was tried – sound film, a whole range of colour technologies, editing, camera movement, large formats, cine-microscopy, even 3-D. It was an exciting time full of creative energy.

Of the various ‘firsts’ of Victorian cinema in Britain, quite a number survive and many are easily available. We should be wary of seeing all these films as primitive proto-types of later film genres as we may miss both the greater cultural context and some of the interesting directions taken by early filmmakers. Many films or sub-genres were particular to their age. So what are some of the unique features of the earliest films? They are characterized first and foremost by their short running time. Films from 1895 tend not to extend beyond about 40 feet, so less than a minute. Our first extant films, with the exception of Le Prince’s films Leeds Bridge and Roundhay Garden Scene (1888), which were not commercially exhibited, are Birt Acres’ The Derby (1895) and Arrest of a Pickpocket (1895) and these were not exhibited by R. W. Paul, who was in business with Acres until 1896, after the much-publicized screening in December 1895 by the Lumière Brothers in Paris.

In a remarkably short space of time thereafter, film was being shown everywhere. The Lumière Brothers rapidly capitalized on the boom and sent out cameramen to produce films in all the major cities to be shown at Cinématographe shows in major theatres. The Lumières’ experience of photography meant that their films were beautifully composed and photographed but their cameramen also seem to have instinctively grasped the best ways to introduce movement into the picture by mounting the camera on a moving object – boat, train, tram or bus. Panoramas and phantom rides are another unique genre of the early film. The views taken by Alexander Promio in London in 1896 may be short but they are highly produced – set ups included a panorama of the Houses of Parliament, taken from a boat on the river (so is both a panorama and a ‘phantom ride’) and the best, Entrée du Cinématographe (1896), is taken outside the theatre in which these very films were shown, the Empire Leicester Square. Far from being a random view taken from across the street, it is arranged with ‘extras’ walking at different angles across the traffic, to create a sense of bustling movement and on the theatre front we can see the hoarding advertising the ‘Lumière Cinématographe’ show. The film of the outside of the auditorium then started the programme of films inside it.

p.26

Single-shot films dominated for a while and British filmmakers were inventive with them. Of course they had several years of Kinetoscope and Mutoscope ‘films’ to copy and improve upon as well as adopting the Lumières’ business model. The Warwick Trading Company, for example, made, commissioned and distributed other producers’ films from 1898, sending cameramen as far as India, Canada and the Alps. Their lavishly illustrated catalogues show the series of views from all over the world that could be purchased by exhibitors, together with comic scenes, sports, lifeboat launches and fire drills, military parades and state occasions. Mitchell and Kenyon were beginning to produce factory gate pictures and other locally commissioned films for showmen in the north of England. Audiences would turn out in great numbers to see themselves on screen. Despite an initial period when early exhibitors had screened film shows for royalty and high society and in spite of the high-end shows such as those at the Palace Theatre of Varieties, the Empire and the Alhambra, it seemed that film shows would be enjoyed mostly for low prices by the working class.

1902 to 1910: Edwardian

Edwardian Britain was a vibrant time for film, full of invention, experiment and change. We know much more about this period from work done in recent years, in particular due to regular centenary programming at festivals and cinematheques, film restoration programmes and video publication in a range of formats (VHS, DVD, Blu-ray, now VoD and online) that have transformed our knowledge of how films were made, why they were made, how they were programmed and how they were received. We know more about the exhibition environment in which the films were shown from fairground booths to the seasonal town hall show which was a precursor of the type of programme that developed in the new purpose-built cinema space. We know more about the other elements that made up the show, the music that accompanied the films, lecturers and film explainers, marketing and merchandising. Reconstructions of the mixed programme in fairground tents, town and village halls and early cinema buildings have given us a flavour of what it was like to go to a picture show at that time. It was the way that the show was put together that determined its success as much as the quality of the films themselves. A typical mixed programme could be constructed and ordered thus: A musical item (roughly synchronised songs were popular at this time); an actuality, say a royal occasion or a report of a far-off military campaign or local film; a comedy, probably of the chase variety; a drama, perhaps an adaptation of a famous literary work; a natural history or science item, a travelogue or interest film; and the big attraction as the finale, which might have been a drama of higher production value or a colour fairy film. Often the programme was rounded off with a comedy to send people home cheerful. These films could come from a variety of countries and producers who were effectively ‘brands’ and began to develop as genres along these lines.

p.27

A brisk international trade grew up with considerable movement between the principal producing nations in Western Europe and the United States. The quest for constant novelty drove development. Multipart scenic films grew into the seven to ten-minute travelogue. The single-scene comedy derived from strip cartoons began to develop into short sketches such as Mary Jane’s Mishap (1903) or the very popular chase format such as in Our New Errand Boy (1905). Multi-shot films had begun almost accidentally when a single-shot narrative was inserted into a phantom ride in the popular Kiss in the Tunnel (1899) in which a couple, played by the filmmakers G. A. Smith and his wife Laura Bayley, are seen kissing in a railway carriage as it goes into a dark tunnel.

The catalogue of the distributor, the Warwick Trade Company, suggested that this scene could be sandwiched between a pre-existing phantom ride of a train going into, then emerging from, a tunnel. The initial impetus was to extend the usable life of the phantom ride films but it very soon occurred to filmmakers to make multi-shot films. James Williamson’s film Fire! (1901) is a good example in which scenes are linked in a kind of tableaux arrangement. The scenes are linked of course by chronology – the discovery of a burning house, alerting the fire station, firemen turning out (already a popular genre), the rescue of the inhabitants taken both from the interior and exterior of the bedroom where people are trapped, but there is also recognizable continuity – a policeman who has discovered a house to be on fire runs out of one scene and into another. William Haggar’s Desperate Poaching Affray (1903) and Frank Mottershaw’s Daring Daylight Robbery (1903) move this idea on with more fluid linking of scenes, and editing began to be a tool filmmakers could use to smooth out a narrative conceived in episodes or based on illustrations; they could also use it to build tension. Mottershaw’s film famously inspired Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery made later that year. Cecil Hepworth’s Rescued by Rover (1905) took narrative continuity to a...