![]()

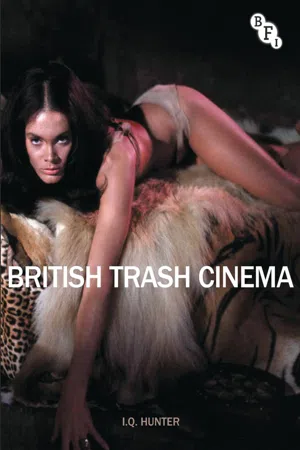

1 BRITISH TRASH CINEMA

This film is quite blatantly directed at a certain type of audience which, unfortunately, does exist.1

I seldom go to see British films for pleasure. I go out of duty, and invariably regret it.2

What is your idea of a proper British picture? A stiff upper-lipped romance in a railway station? A sturdy black-and-white war film with John Mills or Richard Attenborough? Something historical, perhaps, with floppy-haired Englishmen in white flannels and Keira Knightley looking soulful in crinoline? Or one of the great crowd-pleasers: Gainsborough, Ealing, Bond, Carry On, Hammer and Harry Potter?

It has been truthfully said that ‘British cinema, with the best will in the world, is more a carefully constructed illusion than a serious industry’, but the ‘brand’ of British cinema continues to have purchase on the popular imagination.3 A 2012 Film Policy Review paper on the future of the industry after the abolition of the UK Film Council (UKFC), at a time when British films were more successful than for many years, quoted British respondents as citing humour (‘a sort of dark humour’) and authenticity (‘gritty, more like real life’) as the key ‘British values’ that marked a film as British and thereby pleasingly ‘non-Hollywood’.4 In the global marketplace, meanwhile, British films seem firmly identified with classy nostalgia, realism and modest literary ambition. In 1999 the British Film Institute came up with an uncontroversial list of the 100 ‘best’ British films, topped by The Third Man (1949) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and weighted towards the 1960s.5 Consensus was that Britain could be proud of its numerous world classics, most of which were indeed, as you might expect, literary adaptations, ‘heritage films’ and realist dramas in the kitchen-sink tradition. Yet there still clings to British cinema a sense of disappointment, of being, on the one hand, in Hollywood’s shadow and, on the other, subordinate to and even oppressed by the great achievements of British theatre and the novel (for, as a current Waterstones promotion insists, ‘The book is always better’). British cinema for all its triumphs remains awkwardly stranded between art and populism, a nubile Cinderella – to borrow a line from If…. (1968) – sparsely clad and often interfered with.

Debate rolls on about what is meant by a proper British picture. Controversy is sharpest over what kinds of films to support financially so as to promote both commercial success and the national culture. The Eady Levy, which channelled box-office takings back into film production from 1950 till its abolition in 1985, encouraged the international investment that underpinned the sex and horror film boom of the 1960s to the 1970s; and in recent years the doling out of Lottery money through the late UK Film Council led to the funding of a number of barely released, low-budget comedies, horror films and thrillers, such as Sex Lives of the Potato Men (2004) and Straightheads (2007), which, given the heterogeneity of the films supported by the UKFC, earned the Council an undue amount of negative attention.6 The Daily Telegraph in 2004, after the disastrous release of Sex Lives of the Potato Men, which concentrated critics’ minds on the funding and profile of British cinema, complained that, unlike the Arts Council, whose role the UKFC took over in 2000, the Film Council tried to second-guess the market and fund ‘commercially minded’ films, and cited ‘wan little British films that disappear quickly from cinemas’.7 Examples included Bodysong (2003), This Is Not a Love Song (2002), Emotional Backgammon (2003) and Suzy Gold (2004), none of which recouped their budget. Emotional Backgammon sold 209 tickets and grossed £1,056. Needless to say, a film like Sex Lives of the Potato Men is somewhat at odds with a definition of British cinema that rests on Harry Potter (2001–11) and Oscar-bait like The King’s Speech (2010) (also backed by the UKFC). British cinema today ranges from Wuthering Heights (2011) and Skyfall (2012) to Stag Night of the Dead (2011) – all of them, in one way or another, expressive of contemporary Britain, but who is to say which is more properly ‘authentic’? Which represents the ‘true’ British cinema that projects ‘our’ culture to the world?

Sex Lives of the Potato Men: not a proper British film?

CINEMA IN THE RAW

Beyond the heritage of official British cinema, there has always been, for want of a more precise term, British trash cinema – a long tradition of cheap exploitation and improper entertainments that has shocked, appalled, frustrated and delighted in equal measure. Into this makeshift category are grouped all manner of critically and often popularly despised offences against what British cinema ought to be, offences even more blatant than Bond, Hammer and the Carry Ons, which by some standards are quite trashy enough.

Trash represents what Charles Barr emphasised was a key component of British cinema – a ‘strong under-life – represented most powerfully by the horror film’.8 Here are weird, obscure, haphazardly surreal and marginal films, compellingly bad and entrancingly bizarre, the sort of films that mainstream critics disdain or simply never see but which cultists seek out (or rather nowadays click to purchase on amazon.com or download as torrents). Much of this is ‘psychotronic’ cinema, as Michael Weldon called it, condemned by critics ‘for the very reasons that millions continue to enjoy them: violence, sex, noise, and often violent escapism’.9 They especially appeal to that category of film fan, the ‘trash cinephile’ who revels in films exiled from the mainstream and ‘is far too cynical to sit through whimsical romantic comedy, or a big budget event movie’.10

This book outlines some of the key modes of British trash cinema, and their reception by their original intended audiences, but it is also, and in many ways more fundamentally, about the contemporary cult of trash cinema. Many of the films are not cult films – or at any rate not yet, though the field of British cinema as a whole is certainly the object of cult interest. But the reasons for getting interested in these films, and the pleasures they afford viewers today who watch them in a generous and receptive spirit, are absolutely informed by cult. There is then a dual perspective on the films – on the one hand, a neutral view which summarises the history of trash, and on the other, a cult view, not the same as that of the intended audiences, which addresses the films’ particular attractions and, more important, uses for a certain kind of excessively committed viewer.

Most obviously trash cinema includes exploitation and sexploitation films – low-budget horror and science fiction, shoestring sex comedies and softcore pornography, which are typically dismissed as the lowest, most formulaic and sometimes most dangerously corrupting manifestations of film production.11 From the 1950s to the 1980s over 400 exploitation films were made in Britain, ranging from international hits, such as Hammer’s Dracula (1958), to eternal outcasts little seen outside specialist cinemas, such as the sex films Come Play with Me (1977) and Erotic Inferno (1975). They count as trash because they are or were regarded as worthless, disposable and ephemeral junk; in short, not so much bad but disgraceful, and consequently the target of harassment by censors and moral guardians, who in Britain have long been suspicious of cinema’s delinquent energy and popular reach. Cultists have of course revived interest in the margins of cinema, especially horror and sex films, and it is cultists with a taste for low genres, bad taste and bad films, kitsch and the frankly sub-cinematic who are the main enthusiasts nowadays for British films which, however popular at the time, have since fallen by the canonical wayside.

But British trash cinema is arguably distinct from the disreputable cult cinemas of the US and continental Europe. It is less well known, for one thing. Hammer apart, British trash remains a niche cult among cults. It is true that the most celebrated of all cult films, The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), is indeed British, but how many fans of that unique prefabricated trash movie went on to explore Devil Girl from Mars (1954), Psychomania (1973), Toomorrow (1970), Vampyres (1974), Big Zapper (1974), Dirty Weekend and the unforgettable kitsch of Boom and Can Heironymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe and Find True Happiness? (1969)? Most Rocky Horror fans, I suspect, kept their virginity as regards such obscure gems. Yet each of those films can boast a select following of connoisseurs. Many times I’ve witnessed eyes light up in disbelieving recall at the mention of Psychomania – zombie bikers! Beryl Reid turning into a frog! As Fangoria sardonically remarked, that film ‘is an artefact of post-mod British kitsch, admired with irony and worshipped by millions, perhaps thousands, even dozens of cult movie fans around the globe’.12 For, alas, its cultists are few indeed, even in Britain, compared to those of the Italian horror maestro Lucio Fulci, the inept American auteur Ed Wood and, attracting the largest cohort of fans of British films, James Bond.

British trash also – how can I put this? – feels different from other trash cinemas (in ways not all cultists will respond to) thanks to the impact of restrictive censorship and the peculiar social, production and distribution contexts of British film. Although this book trolls through a cinema of transgression, not all of it is a wild ride into excess, subversion and lurid erotic defiance. British trash is also, and perhaps mostly, a cinema of routine underachievement, of stupid sub-B movies, austerity thrillers, unfunny comedies and failed grabs at naughtiness. Sometimes inspired, frequently weird, often sad and desperate – rather, in fact, like Britain itself – our trash cinema opens onto not only a world of exotic pleasures but also one of compromise and impoverishment, thwarted ambition, social embarrassment, silent erotic yearning and suburban boredom. That, being British myself, with a stereotypical fondness for unassuming mediocrity and gallant failure, is reason enough for me to love it.

BEASTS IN THE CELLAR

Trash refers in large part to what Julian Petley in 1986 famously called, borrowing the term from Hammer’s 1968 fantasy, ‘the Lost Continent’.13 Petley, in a foundational article for what I’ll risk capitalising as the New British Revisionism in Film Studies, highlighted the crucial counter-tradition of romance and anti-realism in British cinema, which had been overlooked for reasons of class, aesthetic snobbery and hostility to popular cinema and even, you might say, to cinema itself: ‘an other, repressed side of British cinema, a dark, disdained thread weaving the length and breadth of that cinema, crossing authorial and generic boundaries, sometimes almost entirely visible, sometimes erupting explosively, always received critically with fear and disapproval’.14 This lost continent included not only trash but the saturated romanticism of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, and the Gothic tradition of Hammer and its imitators, as well as the ambitious hybrid art cinema of Ken Russell and Peter Greenaway. Emerging from deeply culturally embedded traditions of fantasy, nonsense and absurd humour, this was a heterogeneous cinema which challenged the subordination of cinema to literature and theatre. Visceral and ‘visual’, boldly mythic and erotic, it had been habitually overlooked by critics committed to realism and the literary. The films, from art house to horror, still challenge dominant conceptions of British cinema and expand its range and remit beyond what cultural gatekeepers allow. Kate Egan makes the crucial point that horror films, for example, and especially modern ones,

are not considered in relation to the idea that they are commercial ventures based around spectacle and fantasy, but are measured against a realist norm, where the logic and plausibility of narrative and characterisation always takes priority over the visual and spectacular.15

Consequently, reviewers tend to ‘view any deviation from the notion that a narrative should be convincing, logical and realistic as evidence of a “bad” film’.16

The keynote of the films of the lost continent was fantasy, even a strain of British surrealism. Many of the films Petley highlighted were popular genre films, which critical convention had overlooked or taken for granted – the horror films in particular. But beyond them is, as well as other genres, unpopular popular cinema – films catering to the wrong people (devotees of sex cinemas, for example), or films barely seen at all, or flops even in otherwise successful genres. Tom Ryall, referring to British cinema in the 1930s, highlights the importance of conceiving of national cinema as being as diverse as the nation it represents. British cinema has always been tor...