![]()

Part I

INDUSTRY MATTERS

![]()

1

HOLLYWOOD BLOCKBUSTERS

Historical dimensions

Steve Neale

Many commentators give the impression that blockbusters are particular to or peculiarly characteristic of New Hollywood cinema – of Hollywood since the advent of Jaws (1975), Superman (1978), Star Trek–The Motion Picture (1979), and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) in the mid- to late 1970s and early 1980s.1 They also give the impression that New Hollywood blockbusters consist almost solely, from a generic point of view, of action-adventure, science-fiction, and disaster films. This chapter seeks among other things to qualify these impressions by locating the New Hollywood blockbuster within a series of historical contexts, both aesthetic and industrial. In doing so, attention will be drawn to the continuities – as well as the discontinuities – between pre- and post-1970s Hollywood cinema, and to some of the films and trends in the New Hollywood blockbuster tradition that run counter to prevailing generic accounts. In this way I hope not only to contest a number of current orthodoxies, but also to lay out the terms for a multidimensional definition of the blockbuster, a definition that encompasses films made before the 1970s as well as films made since then.

The first point to make here is that “blockbuster” as a term has been used both inside and outside the film industry to mean two different things. Originally coined to describe a large-scale bomb in World War II, the term was taken up and used by Hollywood from the early 1950s on to refer on the one hand to large-scale productions and on the other to large-scale box-office hits (Hall 1999: 1–2; Blandford, Grant and Hillier 2001: 26–7).2 The two, of course, are by no means synonymous, as the box-office failure of large-scale productions such as The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964), Ishtar (1987), and The Postman (1997), and as the box-office success of small or medium-sized productions such as Easy Rider (1969), Star Wars (1977), and Ghost (1990) all make clear.3 Thus while some films are produced and marketed as “event films” (to use current industry terminology), others become event films by dint of their growing and unexpected success. Although both can achieve must-see status for contemporary audiences, the distinction remains important. Others will take up the role of audiences in the determination of a film’s blockbuster status elsewhere in this book. Here, to repeat, the focus will be on the industry, on the production of large-scale movies as a matter of industrial policy, on their modes of distribution and exhibition, and on some of the textual and extra-textual features of the movies themselves.

Largeness of scale is a multidimensional – as well as a relative – characteristic. It includes such factors as running time and length, the size of a film’s cast, and the nature, scope, and mode of cinematic presentation of the events and situations depicted. These factors are nearly always related to the size of a film’s budget – large-scale nearly always means high-cost. As is well documented, New Hollywood’s major studios have spent more and more money each year on a handful of large-scale films, calculating that blockbuster productions are likely to become blockbuster hits. (By 1996, $100 million productions, once unheard of, were becoming more common. See “T2 Ushered in $100 mil Era,” Variety, 29 April–5 May, 1996: 153.)4 As is also well documented, these films tend to be heavily pre-advertised and widely released, opening on at least 500 screens either in the summer or during the course of the Christmas period.5 Their blockbuster status is thus marked not only by their scale and their cost, but also by the amount and type of publicity they receive and by the ways in which they are distributed and shown. One of the elements that affects both their cost and their presentation is their deployment of expensive, up-to-date technology. In addition to special effects, I am thinking here of the sound technologies that have been introduced since the mid– 1970s, notably Dolby and digital stereo and their various refinements. As Gianluca Sergi in particular has argued, these technologies have transformed the aural (and hence the audio-visual) nature of contemporary Hollywood cinema, adding new aesthetic and sensual dimensions to the “spectacle” and experience of Hollywood movies.6

However, the New Hollywood era is by no means the first in which Hollywood has invested in high-cost, large-scale films. Nor is it the first in which specially made, unusually lavish, and hence unusually spectacular productions have been marked by special modes of promotion, distribution, and exhibition. Nor, for that matter, is it the first in which expensive technologies – including aural ones – have been deployed to enhance their status, experience, and profits. The introduction of “blockbuster” as a term in the early 1950s coincided with the beginnings of a period of sustained and increased investment in productions of this kind and with the increasing use of an additional term, “epic,” to mark, describe, and sell them. In its review section, Variety labeled Quo Vadis (1951) “A boxoffice blockbuster” (November 14, 1951: 6).7 On its front page on August 1, 1951, under the heading “Back to Multi-Million $ Pix,” it reported that “Hollywood is returning – on a limited scale at least – to the multi-million dollar epic.” “The ‘colossals,’” it continued, “include Warner Bros.’ ‘Captain Horatio Hornblower,’ Metro’s ‘Quo Vadis’ and 20th’s ‘David and Bathesheba’.” What the report was marking was the start of a twenty-year era in which, in the wake of the Paramount case, the break-up of the studio system, declining attendances, and competition from television and other leisure pursuits, the major studios and those new independents whose productions the majors helped to finance and distribute became increasingly involved in the production of films of this kind.

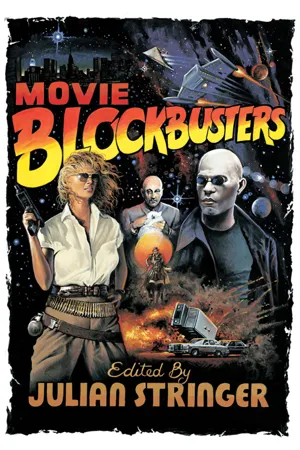

Figure 1.1 A box-office blockbuster: Quo Vadis (1951). The Kobal Collection/MGM.

There were several reasons for this. The Paramount antitrust case meant that the major Hollywood companies were forced to sell off their cinemas and to abandon block-booking their films. Although in some cases the selling-off of cinemas took several years to complete, the combined effects of these rulings meant that companies could no longer guarantee exhibition of all their films and hence could no longer sustain the overheads and levels of production that had marked the studio era. Rapidly declining cinema attendances after the war had in any case already brought about market uncertainty, a downturn in profits, and a series of cuts in studio overheads. Although wage-levels rose for most sectors of the population, newly established families, often in newly established homes in newly established suburbs away from traditionally located cinemas, often chose to spend their money on domestic leisure pursuits, consumer durables, and forms of entertainment other than the cinema. The advent and spread of television, from ownership of whose networks Hollywood’s companies had been legally barred, merely augmented these developments.

As it happened, however, their coincidence for the most part strengthened the position of Hollywood’s major companies. (RKO collapsed in 1957, but by then hitherto smaller companies such as Columbia, United Artists, and Universal had taken its place at the apex of the industry.) The selling-off of increasingly unprofitable cinemas proved a blessing in disguise. The retention of national and international distribution facilities enabled them to garner large shares in the profits available. Freed from the need to service their cinemas, they were able to cut back on the number of films they produced and to share the risks and the profits of production with the new independents who stepped in to fill the gaps opened up by declining studio output and whose ranks were swelled by personnel who no longer were, or who no longer wished to be, studio employees (Balio 1985: 401–573; Belton 1994: 257–60; Schatz 1999: 323–52). At the same time, as a means of sustaining profit and competing for the leisure dollar, they were able to lavish more money on the films they did produce or finance, to invest in new technologies in order to upgrade their product, and in various ways to use the exhibition sector as an enhanced source of income and as a means of upgrading the cinemagoing experience.

By no means all of the films produced at this time were epics, colossals, or blockbusters. But their numbers increased markedly through the 1950s and 1960s as they proved central to most of these strategies. In addition to those cited above, they included The Robe (1953), The Ten Commandments (1956), The King and I (1956), Raintree County (1957), Ben-Hur (1959), Exodus (1960), Spartacus (1960), The Alamo (1960), The Longest Day (1962), Lawrence of Arabia (1962), How the West Was Won (1963), It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), Battle of the Bulge (1965), The Sound of Music (1965), Grand Prix (1967), Krakatoa, East of Java (1969), Hello, Dolly (1969), Paint Your Wagon (1969), and Patton (1970). All of them were expensive, at least three times the cost of the average Hollywood feature at the time they were made.8 Nearly all of them deployed the latest technology, not just widescreen, large-screen or large-gauge processes such as Cinemera (How the West Was Won), CinemaScope (The Robe), VistaVision (The Ten Commandments), Todd-AO (The Alamo, The Sound of Music, Krakatoa, East of Java), Camera 65 (Raintree County, Ben-Hur), Super Technirama 70 (Spartacus), Super Panavision 70 (Lawrence of Arabia, Grand Prix), Ultra Panavision 70 (It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World), and Dimension 150 (Patton), but four-, six-, or eight-track stereo as well (Belton 1992: 113–82).9 Nearly all of them were longer – in some cases much longer – than the average feature (Lawrence of Arabia ran for 216 minutes, Exodus for 213 minutes, Ben-Hur for 212 minutes, and The Ten Commandments for 220 minutes).10 And nearly all of them were either roadshown – “first released to a select few theatres … for separate (rather than continuous) performances, with higher ticket prices and reserved seats” (Blandford, Grant and Hillier 2001: 201) – or distributed and exhibited in other exceptional ways in order to enhance their profitability, showcase their aesthetic and technological features, and highlight their special status.11

Large-scale roadshown productions were by no means unknown in the studio era–indeed at least two of them, Noah’s Ark (1929) and Gone with the Wind (1939), were re-released in the 1950s (the former in a re-edited version with a commentary and soundtrack, the latter in an ersatz widescreen form). There was a flurry of roadshown productions in the late 1920s and very early 1930s. In keeping with the traditions I have sought to underline here, some of them showcased new aural and visual technologies, notably pre-recorded sound and such widescreen and large-screen formats as Magnascope, Vitascope and Grandeur. These films included The Jazz Singer (1927), Four Devils (1928) and The Air Circus (1928), and Old Ironsides (1926), The Four Feathers (1929), Hell’s Angels (1930), The Big Trail (1930), and Kismet (1930) (Belton 1992: 34–64; Hall 1999: 48–56).12 Others, usually also “specials” of one kind or another – most of them showcasing sound as well – were roadshown on Broadway as a means, prior to making distribution deals, of drawing them to the attention of potential exhibitors (Hall 1999: 43).

However, as the Depression began to affect attendances, profits and the relative costs of production, and as the subsequent stabilization of the industry placed a premium on conventional first-run cinemas and the routine weekly provision of A and B features and shorts, high-cost roadshown productions were by comparison few and far between. They consisted for the most part, as Hall points out (1999: 60–6), of “prestige” biopics, musicals, and literary adaptations, of films such as A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935), The Great Ziegfeld (1936), The Good Earth (1937), The Hurricane (1937), The Life of Emile Zola (1937), and Lost Horizon (1937), and they were often only roadshown for a limited period in first-run cinemas. In the era of the double-bill, only a few of these films – notably The Great Ziegfeld at 180 minutes – were much longer than average, and expensive new technologies were rare. But it is worth pointing out that Becky Sharp (1935), the first three-color Technicolor feature, and Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937), the first feature-length cartoon, were both roadshown in the mid-1930s. Subsequently, despite the enormous success of Gone with the Wind – a 1930s prestige “superspecial” which, in terms of its cost, length and lavishness, in terms of its status as independent-studio product, and in terms of its patterns of distribution and exhibition, anticipated many of the features of the postwar blockbuster (Hall 1999: 66–70) – only a few films, such as For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943), The Song of Bernadette (1943), An American Romance (1944), and David O. Selznick’s wartime follow-up to Gone with the Wind, Since You Went Away (1943), sought or were able in wartime industrial conditions to build on the example it set.

While negotiating with MGM to roadshow Gone with the Wind, Selznick wrote an unsent memo to Al Lichtman, MGM’s vice-president. “I think it is as wrong not to road show Gone with the Wind,” he wrote, “as it would have been not to road show The Birth of a Nation [1915]” (Behlmer 1989: 223). In doing so, and in going on to refer in his memo to Ben-Hur (1925), and The Big Parade (1925) as well, Selznick evoked the traditions of the silent roadshown superspecial, traditions which have their roots in the early 1910s. At this point in its history, when the industry in America was geared to the routine production, distribution, and exhibition of daily programmes of single-reel films, roadshowing, along with states rights distribution, was adopted as a means of circulating nonstandard, multireel features.13 According to Balio (1976: 8–9), some 300 films were distributed in this way between 1912 and 1914. Approximately half were American, the other half European (mainly from Italy and France). Among the former were The Coming of Columbus (1912), Tess of the D’Urbevilles (1913), and Judith of Bethulia (1914), among the latter Queen Elizabeth (1912), Quo Vadis? (1913), and Cabiria (1914). Two discernible though often overlapping trends are apparent here: prestige literary or theatrical adaptations on the one hand, and “spectacles” on the other.14 These were to continue into the 1920s (and, as we have seen, into the 1930s, 1940s, and beyond). A year later The Birth of a Nation, whose cost, scale, and earnings are legendary, and whose initial roadshow run lasted through until the early 1920s, helped, as features began to become more routine, to up the stakes and establish the superspecial as an additional type of industrial product.

Among the features of roadshow productions and, increasingly, premieres and first-run presentations in metropolitan movie palaces too, were especially composed or compiled music scores.15 The experience contributed by the performance of these scores augmented the visual spectacle provided not just by the films themselves, but also by the stage performances with wh...