![]()

SECTION ONE

Local environmental justice

Simin Davoudi and Derek Bell

There is an immense need patiently to disseminate information, to dwell repeatedly on the concrete cases of injustice and on the concrete cases of ecological unsustainability. (Naess, 1999: 28)

People care deeply about their local environment because its quality affects their quality of life, wellbeing and contribution to environmental sustainability. Local environmental justice is a critical component of social justice. Like other forms of social inequality, environmental inequalities worsen health and wellbeing, hamper economic development and diminish social cohesion. Environmental justice matters because access to environmental benefits and protection from environmental harms constitutes basic human rights (UNEP, 2001). The history and origin of environmental justice go back to environmental justice movements (EJM) and their links with civil rights movements of the 1950s and 1960s in the United States. This was a time when the poor and predominantly non-white communities suffered most from pollution especially from toxic waste disposals. Today, the political reach of environmental justice has moved beyond race to include deprivation, age, gender and other vulnerabilities. The question of ‘who gets what’ has been extended to include other questions such as ‘who counts’, ‘whose voice is listened to’ and ‘what counts as a legitimate claim’. Similarly, its substantive scope has moved beyond toxic waste and hazards to incorporate a wide range of both environmental ‘bads’ (burdens) and environmental ‘goods’ (benefits). The breadth of issues covered in discussions of environmental justice reflects the pervasiveness of the environment in everyday life.

The four chapters that make up this section of the book address a number of local environmental concerns including, urban greenspace, local schools, transport and food. The authors draw on their knowledge and experience of Newcastle to provide examples of various ways in which people experience justice and fairness in the city. The section starts with Chapter 2, which focuses on urban greenspace and its benefits to local environmental quality and local communities. Drawing on their earlier work, Simin Davoudi and Elizabeth Brooks present a multidimensional framework for understanding justice that goes beyond a concern with the geographical distribution to concerns about recognition, responsibility and capability. Based on this framework, they develop a number of key principles that can be applied to judge claims of injustice in relation to urban greenspace in Newcastle city. The chapter demonstrates how the uneven distribution of greenspace in the city can be interpreted as unfair when it is examined in interaction with other vulnerabilities and inequalities. They put a particular emphasis on the role played by what they call, qualities of and qualities in greenspace in people’s access to and use of this urban environmental asset.

In Chapter 3, Pamela Woolner focuses on the school in the city, attempting to shift the debate away from a sole focus on poor physical quality of schools in deprived areas, to highlighting their potential contribution to improve the quality of the local environment. She argues that, the conventional justice debate about schools focuses on the former and is concerned with its negative impact on learning, teaching and, ultimately, student outcomes. However, Chapter 3 puts the emphasis on the positive role the school in the city can play to address environmental, and perhaps social, injustices. Woolner shows how efforts rooted in improving the school space can create a centre for sustainable living and an environmental resource for the wider community. She demonstrates how this broadened understanding of the role of the school in the city parallels the reconceptions of environmental justice that go beyond simple distributive justice to consider the importance of participation and recognition.

Chapter 4 by Roberto Palacin, Geoff Vigar and Sean Peacock focuses on transport poverty and urban mobility. As the authors argue, social exclusion in transport is double edged in the sense that mobility and accessibility are unevenly given in society and this is reinforced by policy and investment that favours certain modes and speed for a few over accessibility for all. They show how the choices of the ‘hyper-mobiles’ impact disproportionately on the disadvantaged and less mobile sections of society who are also more likely to be subject to the harmful consequences of transportation such as air pollution, road crash, noise and so on. They pay particular attention to two key dimensions of transport poverty, car ownership and public transport service and show how deprived households in Newcastle are disproportionately affected by lack of access to both. More importantly, they argue that poverty can also be experienced by those who are forced to own a car, in spite of their ability to afford one, because no other transport options are available or affordable.

In Chapter 5, Jane Midgley and Helen Coulson discuss the growing concerns about food justice, and show how different aspects of social and environmental justice interrelate with food. They focus particularly on how food justice has emerged as an organising concept for contemporary society and how its development and adoption have been informed by particular political debates. A notable example is the influence of the environmental justice movement on the food justice discourse by drawing attention to the fact that certain communities experience disproportionate lack of access to healthy foods. Midgley and Coulson explore the various practices and institutional arrangements surrounding the urban food systems that can be captured by the notion of food justice, using Newcastle as an example. They argue that without radical reform of the institutional arrangements and practices in urban food systems the pervading structural inequalities and injustices will remain.

The contributions to this section of the book demonstrate the importance of work on environmental justice for understanding justice in and of the city. Together, the four chapters show some of the very different ways that environmental injustices – in access to greenspace, the effects of air and noise pollution in schools, mobility and the effects of the hyper-mobile, and access to healthy food – contribute to the injustice of the city. They highlight the effects of environmental bads on the everyday lives and the life chances of city dwellers already enduring social and economic disadvantages. However, they also illustrate how the reproduction of injustice might be challenged through both planned interventions, such as improving access to greenspace, and community activism, such as local initiatives to tackle food poverty or schools repurposing their outdoor space to create new opportunities for children and the wider community.

This section of the book shows that, like social justice, defining and assessing environmental justice is not straightforward; that questions of justice and fairness are not technical or statistical questions but rather ethical and political questions. The chapters, especially Chapters 2 and 3, illustrate how different theoretical perspectives highlight different injustices. Therefore, identifying and addressing injustice requires theoretically-informed practical judgments about specific cases at specific times and places. So, as Davoudi and Brooks argue in Chapter 2, there is a need to combine quantitative analyses of spatial distributions of environmental benefits and burdens with fine-grain qualitative narratives of how people experience injustices in their everyday life, and what aspects of local environmental qualities matter most to them.

References

Naess, A. (1999) ‘An outline of the problem ahead’, in N. Low (ed) Global ethics and environment, London: Routledge.

UNEP (2001) ‘Living in a pollution free world a basic human right’. UNEP News Release 01/49. [online] Available at: http://www.unep.org/Documents.Multilingual/Default.asp?documentid=197&articleid=2819 [Accessed January 2016].

![]()

TWO

Urban greenspace and environmental justice claims

Simin Davoudi and Elizabeth Brooks

Introduction

The budget for new road building, if used differently, could provide 1,000 new parks at an initial capital cost of £10 million each – two parks in each local authority in England. (CABE study, quoted in Marmot, 2010: 25)

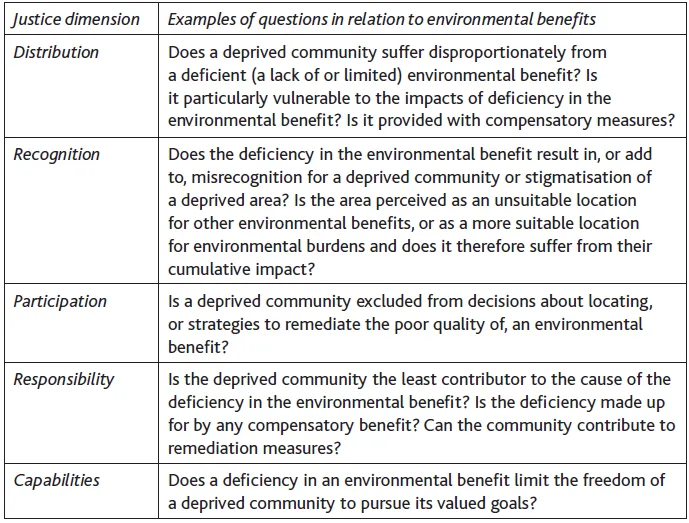

Urban greenspace provides a vivid illustration of the debate over how multiple factors can coincide to turn the distributional unevenness of environmental benefits into a case for claims of injustice. What underpins this debate is a pluralistic understanding of justice that goes beyond distribution to include recognition, participation, capability and responsibility. The focus is not only on who gets what, but also on who counts, who gets heard, what matters, and who does what. Based on this inclusive framework, Davoudi and Brooks (forthcoming) have suggested a set of guiding principles that can be used for judging justice claims about environmental burdens. These, adjusted for environmental benefits, are shown in Table 2.1.

The aim of this chapter is to show how these principles can be applied to the fairness of access to urban greenspace in the city of Newcastle upon Tyne (hereafter Newcastle). More specifically, we aim to explore whether the uneven distribution of greenspace in Newcastle can be interpreted as unfair for this particular case and time. The chapter is structured under four headings. After this introduction, we discuss the significance of urban greenspace as an environmental benefit for human health and wellbeing. We then draw on the justice dimensions and the guiding questions in Table 2.1 to discuss how the uneven distribution of greenspace may lead to claims of environmental injustice. The chapter’s conclusions are drawn together in a final section.

Table 2.1 Guiding questions for judging environmental justice claims

Greenspace as an environmental ‘good’

There is a growing body of literature that underwrites the multiple benefits of urban greenspace. As part of ‘ecosystem services’, greenspaces function as carbon sinks, cooling the temperature, reducing surface water runoff and providing green corridors for wildlife (Heynen, 2006). Greenspace in urban areas reduces the effect of air pollution through biogenic regulation (Freer-Smith et al, 1997), with tree canopies being particularly effective in capturing particles due to their greater surface roughness (Manning and Feder, 1980).

In addition to these environmental benefits, research has shown that urban greenspace is important for people’s physical and mental health throughout their lives (White et al, 2013; UCL IHE, 2014). For example, epidemiological studies have found strong links between health and greenspace in large cities (de Vries et al, 2003), particularly in relation to longevity in the elderly and more generally (Takano et al, 2002; Mitchell and Popham, 2008) and healthy childhood development (Sadler et al, 2010). There is evidence of association between greenspace and a reduced risk of anxiety and depression (Maas et al, 2008). It is suggested that contact with nature can promote better mood (van den Berg et al, 2003), improve attention (Ottosson and Grahn, 2005), provide restorative benefits (Taylor et al, 2002), and enhance self-discipline (Taylor and Kuo, 2009), self-awareness and self-esteem (Maller et al, 2002). There are also social benefits: it is shown that natural settings provide inclusive places to meet that can improve social interaction and cohesion (Bird, 2007). It is also argued that properly managed urban greenspace enhances neighbourhood image and adds to property values (Scottish Natural Heritage, 2014: 2). However, the materialisation of many of these benefits depends on a number of factors such as the availability (size and distance to where people live), accessibility (physical and sociocultural) and quality (actual and perceived) of urban greenspace. While later sections will explore these factors in greater detail, we will first begin by presenting the case study area of Newcastle and its greenspace endowment.

Greenspace in Newcastle city

Newcastle is a birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, which brought wealth for some but created destitution for others and left a legacy of environmental problems. While reducing inequalities has remained a challenge, major progress has been made in reducing the environmental burdens in the city and enhancing its environmental benefits. A notable example of the latter is greenspace, which the city, despite its industrial past, is well provided with. This was a major factor in Newcastle being twice voted (in 2009 and 2010) as ‘the greenest city’ in Britain by Forum for the Future (Forum for the Future, 2010). Some 55% of the city (around 68 km2 from a total of 123 km2) consists of greenspace, of which about one quarter (17 km2) is publicly accessible. A further 5% (6 km2) of the city’s area is water, mainly in the form of the River Tyne, which borders the southern edge of the city and the Ouseburn, which is the Tyne’s main tributary in the city.

The average built up area in European cities ranges from 20-80% (EEA, 2010: 14), so Newcastle with its 40% built up area is positioned in the middle (EEA, 2010: 26). However, Newcastle has a particularly dense built environment with only 7.5% of homes being detached compared to an England average of 22.5%; while over 30% of homes are flats/apartments compared to an England average of 19.3% (NCC, 2011a), indicating the importance of greenspace in the city. In terms of per capita provision, Newcastle has a high level of publicly accessible greenspace standing at 8.4 ha per 1,000 people; however, as will be discussed in the following section, and shown in Figure 2.1, its distribution is not even. Notably, over 20% (4 km2) of the public greenspace is in the form of one large, protected pasture called the Town M...