![]()

INTRODUCTION

Reassessing human resource management ‘with Chinese characteristics’: An overview

Malcolm Warner

Introduction

In a recent study Zhu, Warner and Rowley (2007) discussed the possibility of a system of human resource management (HRM) ‘with Asian characteristics’. The investigation looked at the similarities and differences between Western and Asian systems and asked if there was a ‘hybrid system’ in the making. The People's Republic of China (PRC) (Zhonghua renmin gongheguo) may be offered as a successful example of such a genre, for, as a transitional socialist economy (Warner, Edwards, Polansky, Pucko and Zhu 2005), it is clear that its attempts to open its door in order to reform its economy and its system of people-management have broadly speaking ‘paid off’ (see Budhwar 2004; Zhu and Warner 2004a; Zhu et al. 2007). However, China's reformers did not merely replicate foreign models uncritically. Where they have implanted overseas economic management (jingji guanti) practices since the late 1970s, principally from the US, Japan and Europe (roughly in that order), they did so by incorporating them into the Chinese ‘way of doing things’.

An evolutionary process was consequently set in motion in which organizations that were better fitted to survive in this new environment were to displace others that were less suited (see Hodgson 1997) — and to accomplish this according to the new Chinese ‘rules of the game’ (see Nolan 2003). In terms of how such changes take place, organizational theorists suggest that evolutionary variance may be intentional or blind; variations in new organizations or new organizational populations may occur; selection criteria may be set by market forces, competitive pressures, peer groups and so on (Aldrich and Ruef 2006, pp. 20–21). All the preceding factors are highly relevant occurences in the PRC. As China now had to face the challenges of globalization (quanqiu hua), it adapted its system to promote institutional and organizational characteristics appropriate to a greater reliance on markets (see Qian 2000).

The new paradigm underlying the economic reforms that ensued after 1978 was to be known as socialism ‘with Chinese characteristics’ (juyou Zhongguo tese de shehuizhuyi).1 This particular terminology was employed in the post-Mao period in order to reconcile what might appear to be ‘foreign’ (even ‘capitalist’ and therefore ‘non-socialist’) practices, with indigenous Chinese institutions based on Chinese values, whether traditional or communist — and even appearing to resolve the apparent contradiction. Both the latter, being in their different ways based on ‘collectivistic’ values, would therefore perhaps then be more reconcilable with what appeared to be ‘individualistic’ ones.2 The dilemma was, on the one hand, not to appear to be ‘taking the capitalist road’ (zou zibenzhuyi daolu), a term used to refer to ‘counter-revolutionary’ policies in Maoist ideology, yet on the other hand, not to be seen as eschewing change.3

As economic reform proceeds in a given country, it is likely that a matching innovation in its management system follows (see Child 1994). This generalization appears to fit the Chinese model, as it moved from a ‘command economy’ to a ‘market socialist’ one soon after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976 (see Naughton 1996). The resulting changes in the Chinese ruling elite just after brought about significant shifts in the institutional and organizational environments faced by enterprises (see Li and Walder 2001; Nolan 2003; Aldrich and Ruef 2006, pp. 169–170). The World Bank, membership of which China assumed in 1980 (World Bank 2004, p. 22), sought to optimize ‘resource allocation’ and ‘factor productivity’ in what was seen as an inefficient economy, with loss-making stateowned enterprises (SOEs) at its core (see Granick 1990; Zhang 1996; Naughton 1996, 2006). As a result China began moving, in less time than anyone might have imagined, from ‘plan’ to ‘market’.

Management in the PRC at that key point in time was faced with a ‘strategic choice’ as to how best to cope with the process of modernization. The strategists, i.e. those advising the Party leadership, could: first, leave things unreformed; second, evolve new indigenous forms; third, straightforwardly adapt Western types of management; or fourth, adapt the latter more specifically to its own local environmental conditions, using Western knowledge to implement an evolutionary change process but within the context of Chinese values. They chose the fourth of these options; and in doing so, looked to their cultural roots. This last option, of adaptation, may be subsumed under the rubric of ‘linking up with the international track’ (yu guoji jiegui), a notion that formally emerged in the PRC in the late 1980s (Wang 2007, pp. 13ff) although its roots may be seen even earlier. Emulating the USSR in earlier times, ‘let's be Soviet and modern’ (xiang sulian moshi xuexi, sixian xiandaihua) had been a popular slogan in the 1950s. When Deng Xiaoping's policies were introduced soon after Mao's death, the term ‘linking up with the international track’ entered the language but mostly in the economic realm, particularly in the context of market reform initially. It was soon to be seen in the non-economic arena as well. In public discourse, it referred to Western notions to modernize the country in everything from education to HRM (rent i ziyuan guanti). It soon became a popular idea in the latter domain in place of old-style personnel management (renshi guanti).4 ‘Linking up with the international track’ may be seen as part and parcel of how the PRC has attempted to adapt to globalization but at the same time tried to emphasize ‘Chinese characteristics’, to be seen as retaining its own values and therefore ‘squaring the circle’.

A possible explanatory schema

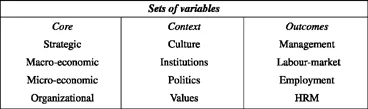

The theoretical dimensions of this evolutionary change-process may be set out as shown in Figure 1.

In a possible explanatory (if admittedly deterministic) schema to explain how the reform process unfolded causally, we sketch out a number of changes in terms of the ‘core’ variables in the system indicated in the left-hand column of Figure 1, as moderated by ‘contextual’ ones in the centre, leading to innovations in the human resources ‘outcome’ variables set on the right. To put it concretely, as the Chinese government adopts a new direction in strategy, a package of economic reforms is then implemented, which in its turn has consequences, directly and indirectly, for management, labourmarkets, employment and HRM. The schema outlined in Figure 2 would link all these levels together and may be seen as endogenously driven in its most straightforward model. It is, however, possible to incorporate exogenous variables in more complex variations of the above, such as responding to the challenges of globalization and the demands of the international economy, as it is arguable that these are as important as endogenous ones. The up-shot, in shorthand, may be seen as uni-linear, in theory at least, in that it appears to drive the systemic relationships between the sets of variables in a single direction, namely from past failures to future gains. However, one can anticipate that the ‘devil is in the detail’ when we see what actually ensued.

As the PRC becomes inexorably linked to the international economy and increasingly faces the challenges of globalization, its enterprises and their managers have not only to adapt to external market pressures, international norms and so on, but at the same time to respond to internal institutional ones (see Guthrie 1999). The tension between these factors, external as well as internal, provides an arena in which managers, as well as workers, now have to cope, perform and survive. The resulting outcomes take on the form of innovative management, nascent labour-markets, new kinds of employment and the implementation of HRM (see Figures 1 and 2).

How did such a change process unfold over time? The stereotypical peoplemanagement model we take as the point of departure is the one which was set up by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) (Zhongguo gongchan dang) within the ‘command

Figure 1. A schema of market-driven human resources reform.

Figure 2. Uni-directional schema of variables.

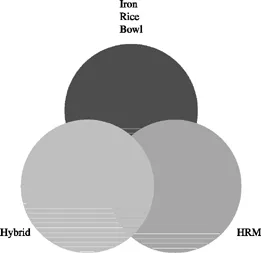

Figure 3. Overlapping people-management characteristics.

economy’ that emerged after the ‘Liberation’ (jiefang) in 1949 (see Schurman 1968). This model had a set of defined characteristics which have been well described in the literature (see Walder 1986) and which can be summed up in the term, the ‘iron rice bowl’ (tie fan wan) a form of ‘life-time employment’ status that workers enjoyed, much of which was derived from the Soviet model (see Kaple 1994) and analogous to yet different from the Japanese one (see Rowley, Benson and Warner 2004) as it was much more egalitarian than the latter. Although this model came with many variations, it was clearly recognizable as a stereotype, but its days, for better or worse, were numbered.

The new point of arrival would have the features of a comprehensive HRM system that would be recognizable to an outside expert, as a strategic function carried out in an organization that facilitates the most effective deployment of people and human capital development (that is, employees) in order to achieve both its organizational and individual goals in a market context (see Cooke 2005, pp. 172ff). In short, the PRC was seemingly moving, from ‘status’ to ‘contract’. The progression described above extends from one extreme point of a spectrum to another, that is, from one end at the point of origin being stereotypically ‘collectivistic’ in its ‘iron rice bowl’ form, to the other as potentially ‘individualistic’ at the HRM point of arrival — but with many intermediate, possibly overlapping positions in-between (see Figure 3). Sometimes, we know where this location is with some precision; other times, we know only the pace of change. Given the transitions noted above, the ‘narrative’ of Chinese human resource management (see Zhu 2005) may thus be seen as taking a recognizable path, from ‘plan to market’, from ‘egalitarian to inegalitarian’ and from ‘status to contract’, unintended consequences notwithstanding.

Economic background

In his attempt to throw off the incubus of the Maoist era, particularly the disorder and waste of the Cultural Revolution years, Deng Xiaoping had to be bold (see Zhang 1996). He soon, for example, institutionalized the ‘Open Door’ (kaifang) and ‘Four Modernizations’ (sige xiandaihua) policies in the years after 1978, a process that was to be an integral part of the ‘modernization’ programme and in turn set in train ‘technology transfer’, both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’. The latter of these would involve, for example, management innovations and new ways of organizing enterprises, including preparing the ground for HRM experiments. Developing labour-markets (laodongli shichang), commodity labour (shangpin laodong) and HRM (renli ziyuan guanti) were to be integral to this demarche, all in order to optimize factor productivity — where the factor concerned was ‘labour’ (laodong). At the beginning, little was spelt out but there was openness to new ideas. If there was a strategy, it had been summed up in Chen Yun's phrase ‘crossing the river by feeling for the stones’ (mo zhe shitou guohe) (see Nolan 1994). Deng Xiaoping reputedly pointed out that, ‘It's a good cat provided it catches mice and it doesn't matter at all whether the cat is black or white’ (wulun heimao baimao, zhuadao haozi jiushi haomao), a phrase that still resonates today (see China Daily 2 August 2004, p. 1).

According to the Asian Development Bank, ‘[T]he People's Republic of China (PRC) has been one of the world's fastest-growing economies in the last two decades and posted another strong year in 2006, expanding by 10.7%. Per capita gross domestic product (GDP) was about US$2,000, and the number of rural poor living below the official poverty line fell to 21.5 million (2.3%) in 2006, from 250 million (30.7%) in 1978, when the Government began market-oriented economic reforms. However, a key challenge to the Government's aim of building a harmonious society is the widening gap between the rich and the poor; rural and urban; and the coastal, central, and western regions of the country’ (Asian Development Bank 2007, p. 1). This account is high praise indeed (if the statistics are credible) though admittedly is delivered with a sting in the tail.

Even so, the pace of economic growth has been remarkable since the start of Dengist reforms (see Wu 2003; Perkins 2006; Naughton 2007), notwithstanding the effects of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests (which soon led to sanctions), the 1997 Asian financial crisis (which slowed down the economy somewhat but much less than elsewhere in the region) and the 2003 SARS epidemic (which led to considerable uncertainty and an initial downturn) (see Rowley and Warner 2004a; Rawski 2006; Lee and Warner 2008). According to official Chinese government statistics, national income has been doubling every eight years. In ‘purchasing-power parity’ (PPP) terms, however, income per capita may be four or even five times higher than the official figure. There were those who thought the pace of growth would substantially slow down but it has not done so, although there have been, and still are, serious fears of ‘over-heating’. The savings ratio remains impressive (around 50%) but, for better or worse, China now shows signs of becoming a ‘consumer society’ (see Gamble 2001; Croll 2006).

The State now runs less of the economy than it did in the past, however. The share of SOEs in total industrial output has fallen from 77.6% in 1978 to less than 30% now, a ‘seachange’. The so-called ‘dinosaur’ SOEs no longer dominate the economy, by either share of output or employment. But there are still some 170,000 SOEs with assets adding up to almost US$1 trillion, in fact more than in any other economy, and it...