eBook - ePub

Marking Modern Times

A History of Clocks, Watches, and Other Timekeepers in American Life

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Marking Modern Times

A History of Clocks, Watches, and Other Timekeepers in American Life

About this book

The public spaces and buildings of the United States are home to many thousands of timepieces—bells, time balls, and clock faces—that tower over urban streets, peek out from lobbies, and gleam in store windows. And in the streets and squares beneath them, men, women, and children wear wristwatches of all kinds. Americans have decorated their homes with clocks and included them in their poetry, sermons, stories, and songs. And as political instruments, social tools, and cultural symbols, these personal and public timekeepers have enjoyed a broad currency in art, life, and culture.

In Marking Modern Times, Alexis McCrossen relates how the American preoccupation with time led people from across social classes to acquire watches and clocks. While noting the difficulties in regulating and synchronizing so many timepieces, McCrossen expands our understanding of the development of modern time discipline, delving into the ways we have standardized time and describing how timekeepers have served as political, social, and cultural tools in a society that doesn't merely value time but regards access to time as a natural-born right, a privilege of being an American.

In Marking Modern Times, Alexis McCrossen relates how the American preoccupation with time led people from across social classes to acquire watches and clocks. While noting the difficulties in regulating and synchronizing so many timepieces, McCrossen expands our understanding of the development of modern time discipline, delving into the ways we have standardized time and describing how timekeepers have served as political, social, and cultural tools in a society that doesn't merely value time but regards access to time as a natural-born right, a privilege of being an American.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Marking Modern Times by Alexis McCrossen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2013Print ISBN

9780226379685, 9780226014869eBook ISBN

9780226015057CHAPTER 1

Time’s Tongue and Hands

The First Public Clocks in the United States

From youth to age the sound is sent forth through crowded streets, or floats with sweetest melody above the quiet fields. It gives a tongue to time, which otherwise would pass over our heads as quietly as clouds, and lends a warning to its perpetual flight. . . . It is the voice of rejoicing at festivals, at christenings, and at marriages, and of mourning at the departure of the soul; and when life has ended we leave the remains of those we loved to rest within the bell’s deep sound. Its tone, therefore, comes to be fraught with memorial associations.

—William Sidney Gibson “Essay on Church Bells” (1854)

When swung, a bell’s clapper, often called its “tongue,” strikes the inside of the instrument, which produces a resonant sound; hammers or mallets can also be used to hit the exterior of a bell to produce a sound. Bells themselves give “a tongue to time,” that is, they make time audible, transforming it from something that might “otherwise pass over our heads as quietly as clouds” into a distinct sound, the sound of time.1 The sound of time can also emanate from a horn, a drum, or any instrument, but the sound of bells has exercised particular power in American towns and cities since the colonial period. “A listener hearing both the striking of the hours and the more solemn pauses marking services or ceremonies,” as the French cultural historian Alain Corbin observes, “has to cast his response in terms of a double temporal system.”2 It was just such a rich and complex temporality that emerged in Philadelphia during the middle decades of the eighteenth century, and persisted into the nineteenth century.

The casting of bells is a venerable tradition that dates to antiquity in both the East and the West. In Western Europe beginning in the thirteenth century, time’s tongue became multivalent; as time became a matter of measure, bells announced the hours, even as they continued to mark occasions.3 Ringing bells demarcated moments in the arc of individual lives, especially weddings and funerals; they announced sacred times (Sabbaths and other holy days); they rang in honor of important civic events, such as martial triumphs or the anniversaries of the births, deaths, and ascensions of rulers; they called attention to emergencies like fires and floods. In addition to these occasions, bells rang to indicate the passage of time itself (curfew bells, hour’s bells, midsummer’s bells, and New Year’s bells).4 The historian Richard Rath perceptively comments that bells “mediate[d] between smaller social structures and larger identities (based in religious beliefs, town, region, nation, and colonial relations).” Bells in early America, he explains, “did more than ring out to the heavens; they rang in the state.” Hung on the most important buildings and at the highest reaches, bells were “the most expensive ornament of English identity.”5

The nineteenth century resonated with time’s sounds; hour’s bells rang throughout American cities and towns, alarms punctuated bedrooms and bunkhouses, gongs and horns dictated action in fields and factories. Catholic church bells rang the Angelus to call devotees to prayer morning, noon, and night. After the 1870s, a few dozen wealthy congregations, mostly in and around New York City, installed big bells to ring the hours and Westminster chimes, which marked each quarter hour with a melody. Clockworks controlled the Angelus bell and Westminster chimes so that they rang at appointed times, thus their sounds contributed to the sense of time as a matter of measure, rather than of occasion.6 But in the biggest cities by the end of the century, the aural world of public time telling began to fade despite the installation of ever larger bells, drowned out by screeching machinery and crowd noise, or dissipated by wide streets, tall buildings, cavernous alleys. The sound of time never completely disappeared, but the contours of time discipline shifted toward modern practices that depended on a seeing public, on visible timekeepers that were at once accurate and precise, and on what E. P. Thompson described as “the inward notation of time.”7 This chapter explores the early history of public timekeepers in the United States by looking closely at the city of Philadelphia, where during the 1820s and 1830s traditional ways of marking public time, particularly reliance on bells, began to give way to modern timekeeping practices and mechanisms.

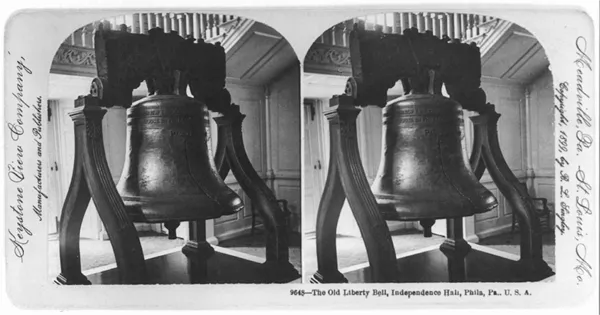

The Old Liberty Bell, 1899, stereograph, LC-USZ62-77866, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

During the colonial period, bells were considerably more important to public timekeeping than clocks. By 1640, more than two dozen towns in Great Britain had installed ringing clocks on their civic buildings. In the 1650s, Boston and Salem each had ringing bells, as did the New York State House, which as of 1656 rang the hours and an evening curfew at nine. A bell known as “the Province Bell” was hung from the crotch of a tree in Philadelphia in 1685, and in 1697 was moved to the cupola of the newly built courthouse.8 Settlements in the interior might have been home to a small clock or sundial, but bells, owing to their expense, were out of reach for most of them.9 In 1713, a clock face was installed on the façade of Boston’s new brick state house, and three years later, New York’s new state house became home to a “paublic Clock with four Dyal Plates.”10 The fledgling nature of American metal casting technologies, the great expense of importing bells of sufficient size, and the difficulties attendant to hanging bells limited the number and extent of bells. Bell towers of various designs appeared in the early eighteenth century in towns along British North America’s Atlantic coast, particularly Charleston, New York, Boston, and Philadelphia.11 Philadelphia’s Christ Church hung a 700-pound bell in 1702 and a much smaller one of 150 pounds in 1711.12 Gradually the colonies were accumulating bells, which after church buildings and state houses were the most important civic and religious accoutrements of the period.

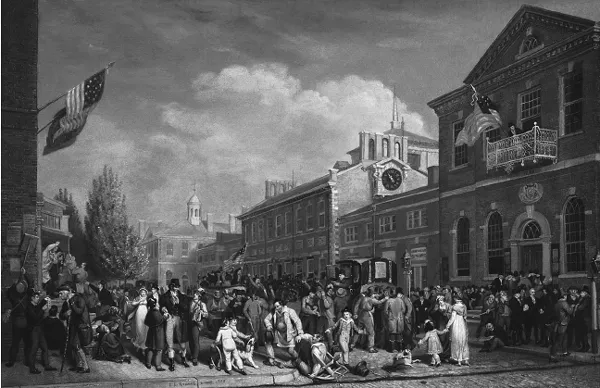

Shortly after the impressive steeple of the Pennsylvania State House (now known as Independence Hall) was completed, a bell from England’s Whitechapel foundry arrived in 1752; almost immediately the one-ton bell cracked. Recast by local brass founders, it was hung the next year with, according to one period account, “Victuals & drink 4 days.” Soon complaints were made about the bell’s tone.13 Recast again, the bell was still found insufficiently resonant. This bell, which would become known as the Liberty Bell owing to the inscription “Proclaim Liberty throughout all the land unto the inhabitants thereof,” was left in the steeple, and another bell meant to ring the hours was ordered from England. When the second bell arrived, it was installed in the state house tower. It was attached to a clock movement (made by local clockmaker Thomas Stretch) situated in the middle of the building. Rods connected two clock dials under the gables of the east and west exterior walls of the state house to the clock movement. An ornamental case of stone, in the fashion of tall-case clock cases, protected the dial on the west wall’s exterior.14 The state house clock movement, clock dials, and bells worked together to enrich and complicate Philadelphia’s temporal rhythms. The new bell rang the hours; the gabled clocks showed the hours and minutes; and the old bell, the Liberty Bell, sounded fire alarms and marked mournful and joyous occasions.

John Lewis Krimmel, Election Day, 1815, oil on canvas, Winterthur Museum. The Pennsylvania State House’s tall-case clock that stood on the building’s exterior wall is prominent in this fanciful painting of an election day. Krimmel, a keen-eyed genre painter, included tall-case clocks in some of his other paintings, such as A Country Wedding (1820) and A Quilting Frolic (1813), in which an ornately cased clock towers in a corner of a bare-floored room.

Shortly after the installation of the state house bell, a lottery raised enough money to finish Christ Church’s new steeple and purchase a ring of eight bells that together weighed eight thousand pounds, but it did not bank enough for a clock, as had been intended.15 These bells, like other church bells throughout the colonies, rang at the opening and closing of markets as well as to bring townspeople to church services, in keeping with practices dating to medieval Europe.16 The ringing of the hours on bells was an infrequent occurrence, owing partially to the rarity of reliable clocks. In terms of timekeeping, as in other spheres, church and state worked together during the colonial period, relying more heavily on bells than clocks to disseminate the time, which typically was the measure of occasions like the opening of a market or the commencement of a religious service.

Neither church nor state had much of a hand in determining the time; that task was left to amateur scientists, jewelers, and clockmakers. Shortly after the installation of the Pennsylvania State House bells and clock, members of the fledgling American Philosophical Society built an astronomical observatory on the house grounds. Although ships had been traversing the world’s oceans for centuries, it was only in the 1750s that a reliable method of navigation emerged in the shape of a marine chronometer. Because this precision timepiece did not lose or gain time despite the vagaries of being at sea, it facilitated the calculation of longitude and thus eliminated some of the mysteries of navigation. Now ports and coasts could be charted, their longitudes determined.17 The half dozen men who constituted the American Philosophical Society wished to make their own contribution to science and navigation. Their observations in 1769 of the transits of Venus and of Mercury from the state house observatory, the colonies’ first astronomical observatory, resulted in the determination of Philadelphia’s longitude.18

Afterward the state house yard observatory was dismantled, and the Philosophical Society’s transit instrument was moved to the south windowsill of the state house tower. The observations made with the transit instrument helped determine Philadelphia’s official time, mean solar time, which was used to regulate the state house clock.19 Thomas Stretch, who made the clock, had maintained and regulated it until 1762, after which time the clockmaker Edward Duffield took over those duties. The talented clockmaker David Ritten-house was already in charge of the Philosophical Society’s tall-case regulator clock, which was kept inside the state house. In 1775, he took over the regulation of the state house clock, relying on, as he wrote in his application for the duty, “astronomical instruments for adjusting it.”20 The clockworks attended to by Stretch, Duffield, and Rittenhouse sent Philadelphia’s official time to the dials on the state house’s tall-case clocks and to its bell and then beyond.

Not everyone in colonial Philadelphia was pleased about having the hours rung on the state house bell. In September 1772, Philadelphians living near the state house petitioned the Pennsylvania General Assembly for relief from “the too frequent Ringing of the great Bell in the Steeple of the State-House.” They complained that the bell ringing “much incommoded and distressed” them, particularly when family members were sick, “at which Times, from [the bell’s] uncommon Size and unusual Sound, [the ringing] is extremely dangerous and may prove fatal.” What is more, the petitioners asserted, the bell was not supposed to ring except on public occasions, such as when the assembly or courts met. The assembly tabled the petition. Shortly thereafter the steeple had grown too rickety to bear the weight of the bells, and no mention is made in historical sources of their ringing between 1773 and 1781.21

Despite the interest of the account of distress the bell caused, a complaint not as unusual as might be thought, we should focus on the disavowal of the utility of ringing the hours.22 The petitioners claimed that announcing the hours served no public purpose except during the brief periods of legislative and judicial sessions. This might lead one to suspect that residents of Philadelphia did not yet have a use for the hours, except with regard to coordinating the meetings of governing officials. Such a conclusion would be misguided. Rather than living in a state of natural time where the hours did not matter, Philadelphians, like other colonials living in British North America, consulted a variety timekeepers and followed several different temporal systems including clock time. If they wished to know the hour, they looked to their clocks, watches, sundials, or the sun itself. But the arrival of ships, wagons, storms, full moons, nightfall, harvests...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction. Unveiling the Jewelers’ Clock

- Chapter 1. Time’s Tongue and Hands: The First Public Clocks in the United States

- Chapter 2. Clockwatching: The Uneasy Authority of Clocks and Watches in Antebellum America

- Chapter 3. Republican Heirlooms, Instruments of Modern Time Discipline: Pocket Watches during and after the Civil War

- Chapter 4. Noon, November 18, 1883: The Abolition of Local Time, the Debut of a National Standard

- Chapter 5. American Synchronicity: Turn-of-the-Century Tower Clocks, Street Clocks, and Time Balls

- Chapter 6. Monuments and Monstrosities: The Apex of the Public Clock Era

- Epilogue. Content to Look at My Watch: The End of the Public Clock Era

- Notes

- Index