- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Amusement parks were the playgrounds of the working class in the early twentieth century, combining numerous, mechanically-based spectacles into one unique, modern cultural phenomenon. Lauren Rabinovitz describes the urban modernity engendered by these parks and their media, encouraging ordinary individuals to sense, interpret, and embody a burgeoning national identity. As industrialization, urbanization, and immigration upended society, amusement parks tempered the shocks of racial, ethnic, and cultural conflict while shrinking the distinctions between gender and class. Following the rise of American parks from 1896 to 1918, Rabinovitz seizes on a simultaneous increase in cinema and spectacle audiences and connects both to the success of leisure activities in stabilizing society. Critics of the time often condemned parks and movies for inciting moral decline, yet in fact they fostered women's independence, racial uplift, and assimilation. The rhythmic, mechanical movements of spectacle also conditioned audiences to process multiple stimuli. Featuring illustrations from private collections and accounts from unaccessed archives, Electric Dreamland joins film and historical analyses in a rare portrait of mass entertainment and the modern eye.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Electric Dreamland by Lauren Rabinovitz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

North American History

Introduction

ARTIFICIAL DISTRACTIONS

What more ludicrous and what more sad than the spectacle of vast hordes of people rushing to the oceanside, to escape the city’s din and crowds and nervous strain, and, once within sight and sound of the waves, courting worse din, denser crowds, and an infinitely more devastating nervous strain inside an enclosure whence the ocean cannot possibly be seen? Is it thus they seek rest, by a madly exaggerated homeopathy? Is it thus they cure Babylon, not with more Babylon, but with Babel gone daft?

The urban worker escapes the mechanical routine of his daily job only to find an equally mechanical substitute for life and growth and experience in his amusements…. The movies, the White Ways, and the Coney Islands, which almost every American city boasts in some form or other, are means of giving jaded and throttled people the sensations of living without the direct experience of life—a sort of spiritual masturbation.

AT THE TURN OF THE LAST CENTURY, AMERICA GOT SERIOUS about amusement. Nightclubs, restaurants, vaudeville, melodrama theaters, dime museums, penny arcades, and all kinds of commercial entertainments flourished: “artificial distraction for an artificial life,” lamented the minister Rollin Lynde Hartt about these new amusements taking over cities and towns.1 In his consternation about a new public culture dedicated to the consumption of enjoyment rather than moral and aesthetic uplift, this social critic flags the start of what is today considered popular culture. Among the litany of amusements that preoccupied both the public and the preacher, two stand out for the novelty of their technological bases as well as for the attention—both welcome and unwelcome—that they attracted: the amusement park and motion pictures.2 Amusement parks and movies appeared simultaneously—between 1894 and 1896—and succeeded rapidly, often in relationship to each other. Over the subsequent fifteen years they separately and together became wildly popular across the country.

More than other types of available contemporary commercial leisure, amusement parks and movies represented new kinds of energized relaxation that also functioned to calm fears about new technologies and living conditions of an industrialized society. Together, they helped to define a modern national collective identity regardless of where their subjects actually lived in the United States or who they were. During an era in which there were numerous efforts to define a sense of national belonging through popular or vernacular expressions and rituals (e.g., Fourth of July parades, “The Pledge of Allegiance” adopted in 1893), amusement parks and movies combined industrialized experiences with a sense of a new national corporate culture steeped in manufacturing. They represented uniquely modern mechanized responses to turn-of-the-century American culture. More than burlesque, cheap theater, or dance halls, amusement parks and movies taught Americans to revel in a modern sensibility that was about adapting to new technologies, to hyperstimulation analogous to the nervous energies of industrial cities, to mechanical rhythms and uniformity, and to this perceptual condition as itself American.

THE RISE OF AMUSEMENT PARKS AND MOTION PICTURES

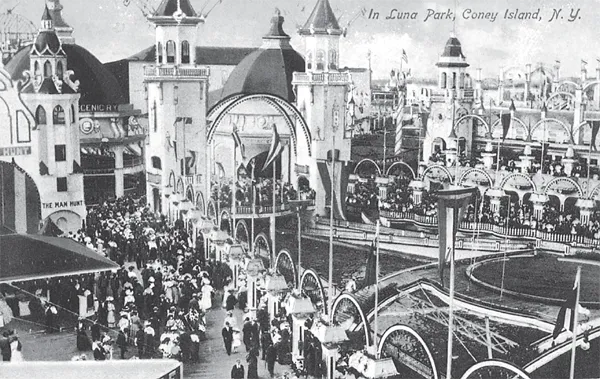

After the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition’s midway demonstrated the popularity of an entertainment zone couched in exotic foreign shows and the technological utopianism of its massive Ferris wheel, entrepreneurial showmen tried to mimic the midway’s style and success. Chutes Park—organized around a mechanized toboggan waterslide—opened one block away (at 61st Street and Drexel Boulevard) from the exposition grounds almost as soon as the world’s fair closed. It was a short-lived attempt to capitalize on the success of the fair’s midway by making amusement a continuous affair. Famed showman Paul Boynton, the owner of Chutes, left Chicago after only one season to open a second water and animal park at Brooklyn’s Coney Island, a district that had housed everything from luxury hotels and ballrooms to gambling dens, a racetrack, and saloons. Two years later, George Tilyou opened another enclosed park charging admission—Steeplechase Park—next door to Boynton’s Sea Lion Park. In 1903 Boynton sold Sea Lion Park to Frederic Thompson and Elmer “Skip” Dundy, and they reopened it as Luna Park (fig. 1.1), a full-scale amusement park featuring fanciful architecture, mechanical rides, shows, animals, and restaurants. In its first season Luna Park achieved forty-five thousand admissions in a single day.3 One year later, a third park styled after Luna (Dreamland) opened to equal success. By 1909 the combined daily attendance of Coney Island’s three parks reached half a million, and these parks served as models for amusement parks opening across the nation.4

Around the country existing parks metamorphosed from picnic grounds, gardens, and zoos to enclosed amusement parks that mimicked Coney Island’s new parks. From New England to the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Coast, parks added mechanical attractions, live theater, moving pictures, and pyrotechnical displays. For example, Lake Compounce in Bristol, Connecticut, had a long history as a picnic grounds. In 1895 it began adding attractions, and by 1911 it was a full-fledged amusement park. Palisades Park in Fort Lee, New Jersey, started as a bucolic nature preserve in 1898 but began to compete with Coney Island in 1907. Even in the country’s heartland, Riverside Park in Hutchinson, Kansas, had housed a zoo since 1888 but in 1902 became an amusement park. Denver’s Elitch Pleasure Gardens began as a zoological garden in 1890 and, over the next twenty years, added numerous mechanical rides, as well as a pyrotechnical show and motion pictures. As far away from Coney Island as the regionally isolated copper mining town of Butte, Montana, Columbia Gardens—which had been a children’s playground and garden since 1899—added a zoo, mechanical rides, a dance pavilion, and motion pictures as soon as amusement parks and movies established themselves as popular entertainments. In California the seaside resorts of Ocean Park (Santa Monica) and the Boardwalk (Santa Cruz) both added mechanical attractions early in the century.

Where there were no such parks, new ones were built. Chicago added five amusement parks to compete with Chutes, and by the time that Chutes went out of business in 1907, half a million people, roughly one quarter of Chicago’s citizens, visited the area’s amusement parks on an average summer weekend in 1908.5 In other midwestern industrial cities like Columbus, Ohio, Oletangy Park boasted a regular Sunday attendance of a quarter of its population.6 Booming railroad towns like El Paso, Texas, could count on half of the town at their amusement parks on a summer holiday.7

Amusement parks were especially plentiful and popular in outlying suburbs of fast-growing industrial cities, where attendance on a special holiday could reach as high as 70 percent of the metropolitan population.8 As the El Paso example demonstrates, these parks were not just restricted to the Northeast and Midwest industrial belts. Electrified amusement parks sprang up in all regions of the country. By 1912 there were as many as two thousand amusement parks nationwide.9 Americans flocked to them for mechanical rides, electrical illuminations, live entertainment, crowd experiences, and recreation.

Electric amusement parks were not the only new carnivals of noise, light, and motion sweeping the nation. Movies “began” in the United States on April 23, 1896, when they were shown in Koster and Bial’s Music Hall in New York City. (The first actual public screening of motion pictures occurred in Paris in December of 1895.) More than twenty-five U.S. cities introduced motion pictures in the summer of 1896. (Summer was a good time to introduce movies because so many vaudeville acts went on vacation, and so many theaters closed completely during the heat.) Cinema’s growth depended on the development of the equipment necessary to make and show movies. It owed an equally important debt to magic lantern shows, illustrated lectures, stereopticons, kinetoscopes, panoramas, and other commercial entertainment that all set the stage for movies, their topics and stories, and the ways they depicted subjects in motion.10 As one Chicago newspaper reviewer said in 1896, “[Moving pictures are] a combination of electrical forces reproducing scenes from life with a distinctiveness and accuracy of detail that is almost startling, bringing out on the canvas screen on the stage not only the outlines but the details of color, motion, changeable expression.”11 At their outset movies represented themselves as both by-products and conveyors of electrification that employed a variety of projection machines—biographs, kinodromes, vitascopes. Like amusement parks, they represented new technologically driven arenas for the consumption of pleasure in a modern industrial age.

In many parts of the country the first motion pictures appeared as parts of shows run by itinerant lecturers and camera operators who traveled from town to town.12 Some showmen used a combination camera-printer-projector to film local scenes and people, develop and print the results, and project the movie to the town’s residents the next night.13 Thus, early cinema was always a combination of mass-reproduced culture (certain images) and unique local events (special material, accompanying lectures, and the exhibitor’s own arrangement and presentation of the show).

In 1898 the novelty began to wear off. Movies might have become a passing fad were it not for the Spanish-American War. U.S. intervention in Cuba and the Philippines provided new subjects that played to sold-out cheering, whistling, handkerchief-waving audiences. These shows combined views of actual American battleships and troops (Soldiers at Play, [Selig Polyscope Company, 1898]), reenactments of naval battles (The Battle of Manila Bay [Vitagraph, 1898]), and patriotic scenes of flag waving, the U.S. cavalry, or Uncle Sam (Raising Old Glory over Morro Castle [Edison, 1899]).14 Charles Musser suggests their key role in consolidating nationalist identity in a new imperial era: “Much has been written about the yellow journalism and jingoistic press of Hearst and Pulitzer, but cinema complemented these efforts in a way that made them much more powerful and effective. Moving pictures projected a sense of national glory and outrage.… Cinema had found a role beyond narrow amusement, and this sudden prominence coincided with a new era of overseas expansion and military intervention.”15 These movies proved they were a new cultural force in their combination of journalism and patriotism.

Moving pictures flourished in vaudeville houses (located in commercial strips, as well as in amusement parks), and the films themselves began the transition from documentary subjects to more story-oriented films. The earliest movies were often scenes from everyday life (actualités) that made it possible for producers to keep up a steady supply of fresh subjects since a portable camera could film any view anywhere. Among early popular subjects were trick films (movies that included “magic tricks” created by stop motion or superimposition techniques), theatrical acts, play excerpts, vaudeville and stage stars, comically acted jokes, scenes from the male world of prizefighting or bodybuilding, and girls performing risqué dances.16

Then, in 1905—separate from motion pictures playing as “acts” in vaudeville houses—small storefront theaters began to show programs of movies. It is a commonplace that Harry Davis’s Nickelodeon, which opened in Pittsburgh in June 1905, gave rise to the spread of such storefront theaters and also inspired the term nickelodeon for venues that charged a nickel or a dime for continuous programs of movies, illustrated songs, and live acts.17 Many nickelodeons made audience participation and crowd conviviality part of “the show” through added sing-alongs and amateur shows. Indeed, the live entertainment at many nickelodeons played specifically to local immigrant audiences and often provided opportunities for local amateurs to sing or dance for small sums of money.18 Film scholar Miriam Hansen explains, “The cinema… provided a space apart and a space in between. It was a site for the imaginative negotiation of the gaps between family, school, and workplace, between traditional standards of sexual behavior and modern dreams of romance and sexual expression, between freedom and anxiety.”19 With cheap prices, easy accessibility on commercial strips or at amusement parks, and continuous schedules that allowed passersby to drop in throughout the day and evening, small theaters flourished.20

By the end of 1906 the number of nickel theaters had climbed from a dozen or so in a few cities like New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Pittsburgh to hundreds. Chicago had more than 300 theaters by 1908 and 407 by 1909.21 By 1908 Manhattan had somewhere between three hun...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Introduction: Artificial Distractions

- 2. Urban Wonderlands: The “Cracked Mirror” of Turn-of-the-Century Amusement Parks

- 3. Thrill Ride Cinema: Hale’s Tours and Scenes of the World

- 4. The Miniature and the Giant: Postcards and Early Cinema

- 5. Coney Island Comedies: Slapstick at the Amusement Park and the Movies

- 6. Conclusion: The Fusion of Movies and Amusement Parks

- Appendix: Directory of Amusement Parks in the United States Prior to 1915

- Notes

- Films Cited

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- Series List