- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Benjamin R. Cohen uses the pure food crusades at the turn of the twentieth century to provide a captivating window onto the origins of manufactured foods in the United States.

In the latter nineteenth century, extraordinary changes in food and agriculture gave rise to new tensions in the ways people understood, obtained, trusted, and ate their food. This was the Era of Adulteration, and its concerns have carried forward to today: How could you tell the food you bought was the food you thought you bought? Could something manufactured still be pure? Is it okay to manipulate nature far enough to produce new foods but not so far that you question its safety and health? How do you know where the line is? And who decides?

In Pure Adulteration, Benjamin R. Cohen uses the pure food crusades to provide a captivating window onto the origins of manufactured foods and the perceived problems they wrought. Cohen follows farmers, manufacturers, grocers, hucksters, housewives, politicians, and scientific analysts as they struggled to demarcate and patrol the ever-contingent, always contested border between purity and adulteration, and as, at the end of the nineteenth century, the very notion of a pure food changed.

In the end, there is (and was) no natural, prehuman distinction between pure and adulterated to uncover and enforce; we have to decide. Today's world is different from that of our nineteenth-century forebears in many ways, but the challenge of policing the difference between acceptable and unacceptable practices remains central to daily decisions about the foods we eat, how we produce them, and what choices we make when buying them.

In the latter nineteenth century, extraordinary changes in food and agriculture gave rise to new tensions in the ways people understood, obtained, trusted, and ate their food. This was the Era of Adulteration, and its concerns have carried forward to today: How could you tell the food you bought was the food you thought you bought? Could something manufactured still be pure? Is it okay to manipulate nature far enough to produce new foods but not so far that you question its safety and health? How do you know where the line is? And who decides?

In Pure Adulteration, Benjamin R. Cohen uses the pure food crusades to provide a captivating window onto the origins of manufactured foods and the perceived problems they wrought. Cohen follows farmers, manufacturers, grocers, hucksters, housewives, politicians, and scientific analysts as they struggled to demarcate and patrol the ever-contingent, always contested border between purity and adulteration, and as, at the end of the nineteenth century, the very notion of a pure food changed.

In the end, there is (and was) no natural, prehuman distinction between pure and adulterated to uncover and enforce; we have to decide. Today's world is different from that of our nineteenth-century forebears in many ways, but the challenge of policing the difference between acceptable and unacceptable practices remains central to daily decisions about the foods we eat, how we produce them, and what choices we make when buying them.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pure Adulteration by Benjamin R. Cohen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Food Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2019Print ISBN

9780226816746, 9780226377926eBook ISBN

97802266670961

The Appearance of Being Earnest

It’s 1879. The courtroom in Santiago is full. The tables and benches and sidelines hold a defendant, his accomplice, the lawyers for all sides, the justice of the Chilean supreme court, and onlookers. The trial had dragged on for two years. The defendant was incarcerated all the while at the nearby Des Hotel Ingles. This autumn afternoon was the end of a very long journey.

Up to that point in life, the accused had “engaged the most elegant suite of rooms in the most fashionable hotels,” charming investors with his “large, eloquent eyes.” Having spent the prior decade crisscrossing half the globe from Europe to North America to South America, he was the man papers from the United States to New Zealand called “foremost in the ranks of the world’s swindlers,” the man who they said had “the black heart of a conscienceless scoundrel,” the one the New York Times devoted ten long paragraphs to in his obituary six years later as the “king of swindlers.”1

He was the Chevalier Alfred Paraf.

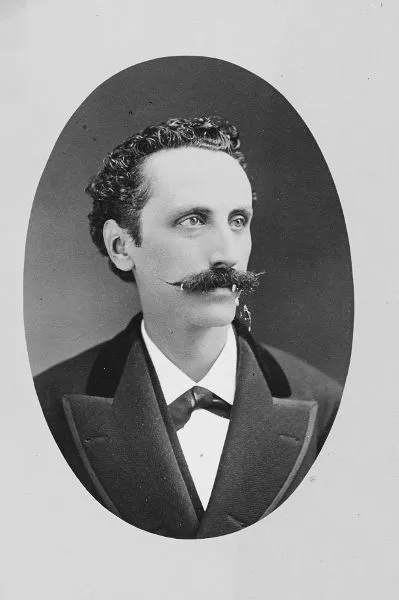

Paraf was a Frenchman. He was born on June 10, 1844, in the Alsace region near the Rhine. He’s not part of historical memory anymore, though the image of his deceptive capacity was a stock reference in stories about swindlers for decades. He had, such sources say, a big personality and a winning smile. He had, they said, “the suave address of a gentleman.” And of course he had a wax-tipped moustache. One paper described him as a man with “the form and features of an Apollo” to match “the polished manners of a citizen of the world.” Another called him “handsome, polished, well educated, known for his keen intelligence and ready wit.” In an age of confidence men—con men—a Brooklyn daily said of Paraf that he stood “above and beyond his fellows, who, compared with him, were mere bunglers in operations which he had reduced to an exact science and of which he was the greatest . . . exponent.”2 From Alsace to Scotland to New York to Rhode Island to San Francisco to Nevada to Chile, Paraf made his name as “handsome, refined, clever, brilliant, extravagant, immoral and audacious” (fig. 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1. Chevalier Alfred Paraf. He had this portrait taken in 1873 while in San Francisco at the studios of Bradley and Rulofson. Courtesy of Columbia University.

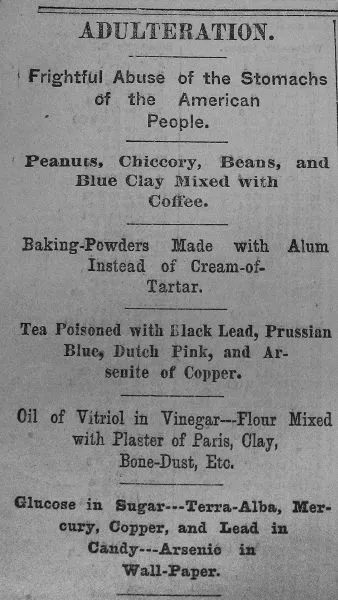

FIGURE 1.2. Chicago Tribune reports on antiadulteration legislation, February 9, 1879.

His cheat? His crime? His unconscionable deed? What prompted the New York Times to anoint him the “king of swindlers”?

Fake butter. Oleomargarine. The scourge of dairy natures.

Paraf was an adulterator. He made artificial versions of natural things and sought to pass them off as equivalent. Adulteration is the term long used to describe the contamination, deception, or false substitution of one product for another. In the nineteenth century, the term was increasingly used to refer to suspicious foods. Some of the Chevalier’s milder accusers found it inappropriate. Others—the ones resorting to black-hearted, conscienceless-scoundrel-level rhetoric—clearly didn’t mince words, framing his crimes as an assault on moral propriety.3

Such critics slammed oleomargarine as a purported adulterant of butter. It was a manufactured product from the factory, not the result of a natural agricultural process. It was wrong, contemporaries thought, because it went against nature. In the century to come, many people would think of it as a cheap substitute for butter. Some would see it as a sign of progress while others would continue to see it as a corruption of the good and the right. Granted, in the particular case of margarine the product’s evolution in public consciousness has been so great that rather than concealing the deception, by the later twentieth century advertisers took it as a point of pride that consumers could be tricked—we couldn’t believe it’s not butter. Yet that eventuality was hardly a foregone conclusion. In the decades after its invention in 1869, margarine was cast by some as “the most gigantic swindle of our time.” The charges against it were serious and severe. “The Cow Superseded,” said the San Francisco Chronicle. “That atrocious insult to modern civilization,” if we follow the Washington Post.4

The handsome Chevalier may thus have become famous as the proprietor of the oleo swindle, but his crimes and stature far exceeded that singular product. They were tapping into a larger crisis of confidence and trust by highlighting the contested ethics of purity, nature, and artifice. Similarly, for some, margarine itself may have been a particularly egregious affront to the nature of the cow—the nature of an agrarian world—but its presence was accompanied by a laundry list of artificial products and suspected contaminants entering the new marketplace of the Victorian world. As the frontispiece has it, margarine was one head of a three-headed hydra of adulteration, cottonseed oil (fake olive oil and fake lard), and glucose (fake sugar), and even those were but a sampling of the wider concerns afoot. Milk and sugar, coffee and tea, mustard and ketchup, baking powder, bread, butter, cheese, flour, olive oil, honey, candy, spices, vinegar, ice, beef, pork, lard, fertilizer, beer, wine, canned vegetables—these were all under suspicion of having been contaminated or debased, the blame falling variously on farmers, manufacturers, distributors, grocers, even potentially paid-off inspectors. The entire panoply of the food system was under suspicion at one point or another from one view or another.

How did these suspicions come to be? Where did the era of adulteration come from? Where did it leave us?

The questions bear a few kinds of answers. Paraf’s background offers a specific one. The broader background of culture, environment, and science in the nineteenth century adds another. This book, as a whole, takes those together to provide a third.

As for specifics, for his part Paraf was the son of a successful dye maker in Mulhouse, a town near the Rhine River about halfway between Strasbourg and Basel.5 The area was a hotbed of manufacturing development by midcentury and the seedbed for a chemical revolution over the next half century. To speak of chemistry at the time was to speak of a craft trade devoted to animals, vegetables, and minerals. In the history of science, agricultural chemistry was coming into its own, animal chemistry was thriving, and plant chemistry was an active focus for scientists, dye makers, and druggists alike. Agricultural and manufacturing efforts were often of a piece, all common stages in the exchange of organic material. Fabrics and textiles were woven in mills from the fibers of the land; colors were mixed from extracts of plants; the bulk of new foods drew from combinations of plant and animal oils and fats; and chemists served as aids to the processes.

The young Paraf’s chemical prowess began with training from his father. At age fourteen, he went to study in Paris at the Collège de France. His skills gave him access to a profitable trade. He would have over a dozen patents before he was thirty. In his early twenties, though, he was bored and restless.

With traveling money from his generous father, he set out in the early 1860s for Glasgow. It was there that his chicanery began. Having quickly lost his cash on ostentatious living, he devised and sold a new calico dye from a fragrant plant called weld (Reseda lutea). The color, it happens, wore off after minimal use. That wearing off was long enough after its application for Paraf to hightail it back to France before he was caught. He was a spry twenty-three-year-old, there just long enough to bilk his own uncle of thousands in another scam before crossing the Atlantic to New York in 1866 or 1867 (reports differ).6

“Asunto Paraff”—The Paraf Situation, to quote later Peruvian sources—blossomed in Manhattan. He met, courted, and wed Leila Smith, the daughter of a high-profile New York lawyer, C. Bainbridge Smith. He took side trips to New England to advance his dye-making funds, at one point fleecing the former Governor of Rhode Island out of tens of thousands. He lived lavishly in midtown Manhattan and dined at only the most posh houses, Delmonico’s among them. He launched a new manufacturing facility with a pilfered patent. Paraf had a lot going on: a lady to woo and marry, a new industry to start, patents to file, appearances to keep up, investors to dupe, creditors to flee. Here was a man on the move.7

He moved quickly not just geographically but in business dealings too. Because he was a learned and wealthy man and a notably suave chemist, Paraf identified and then collapsed the cultural distance between the unknown and the trustworthy. He filled that space with metrics of confidence and the veneer of respectability and allure. In fact, had he been “only a brilliant swindler, obtaining gold and silver from old boots and creating fortunes out of the refuse of tar barrels,” wrote the Brooklyn Eagle, “the world would have been content to let him squander the money he acquired so easily without grudging him his meteoric prosperity or demanding his punishment.” But no, while the American people may have borne “forgery, defalcation [, and] hypocrisy,” what he did was “an act too base for characterization.” It was, his advocates would write, “the crowning work of his active intellectual life.”8 “What he did,” his detractors would shout, “was to introduce oleomargarine, a vicious substitute for butter.”9

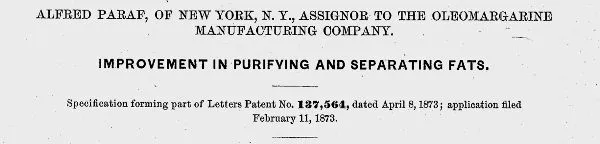

What he did, in short, was to compound worries over the artificial. His character was questionable and insincere, a fake, just as his product was viciously replacing an icon of the agrarian dairy. What is more, he claimed the patent for oleomargarine as his own. But he had nabbed it from his fellow Frenchman, Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès. The Mège Patent, as it was later called, had been motivated by the coming Franco-Prussian War of 1870. As early as the 1867 World Exposition in Paris, Napoleon III was encouraging animal chemists to develop a cheaper substitute for butter, all the better to save important milk and dairy stores for the troops. Mège mixed milk with heated and refined animal fats—tallow from rendered beef suet for its stearin and olein—to reduce the dairy content of butter.10 A new product was born. Paraf thus misrepresented his relationship to the invention of a product that people feared was a misrepresentation of natural butter (fig. 1.3).

FIGURE 1.3. Header of Paraf’s original ill-gotten patent for “Improvement in Purifying and Separating Fats,” that is, oleomargarine, approved on April 8, 1873, two months after filing it and three years after stealing the recipe.

Stolen recipe in hand, Paraf charmed investors in New York into establishing the Oleomargarine Manufacturing Company in 1873. While maneuvering to start the company, he had meetings with the eminent though undoubtedly less suave chemist Charles Chandler. Chandler—a professor at Columbia’s School of Mines (1864), the first chemist of the newly chartered New York Board of Health and its Anti-Adulteration Division (1866), and soon a founding member of the American Chemical Society (1876)—dismissed the young man as a curiosity without much comment. Some later reports claimed that Paraf had “studied with Chandler” while in New York. If so, the things he studied were not academic.

Paraf stayed a step ahead of those who would question him by heading west later in 1873. Ostensibly at the invitation of capitalists in California, he helped build the new California Oleomargarine Company in San Francisco. In a show meant to build public trust, the company hosted a demonstration of the process in October. The public display was a hallmark maneuver of con men; it was not a big step from Paraf’s margarine to Barnum’s circus to the carnival of historical tricksters engendering trust through purportedly transparent demonstrations. Supporters published in local papers the invitation to see “the matter explained lucidly by Professor Alfred Paraf” and sent formal letters to prominent figures, including Professor Chandler in New York. “Advancement and invention are seen everywhere,” the authors wrote, “and the latest and most important discovery is one that has enabled the inventor to achieve a victory over animal matter.” Included with the invitation was a glossy biography of the handsome Chevalier (fig. 1.1). The text matched the image. The biography painted a picture of unsullied character with inventive prowess.11

While in California, Paraf entertained an audience with past governor and soon to be senator Leland Stanford. Here was the president of the Central Pacific and Southern Pacific Railroads, the man who hit the spike in Promontory, Utah, in 1869 connecting the transcontinental line, the later benefactor of the university founded in his name. Stanford the robber baron likewise dismissed Paraf without losing any money, and in this case of a swindler’s meeting you have to think that perhaps it takes one to know one.

As he traveled in San Francisco, his investors back east had found that he stole—“filched,” they said—Mège-Mouriè’s invention. They dispatched representatives to Paris to secure the rightful use of the Mège patent. Upon return, they kept making the oleo while renaming and reorganizing the venture as the United States Dairy Company.12 A new name and constitution would distance themselves from their ill-gotten founding.

News traveled quickly along the telegraph lines strung beside those same new rail lines that brought Paraf west. The Chevalier was arrested in California with an associate on August 4, 1874, “under an indictment for forgery.”13 Bail was set at $10,000.

It didn’t dissuade him. He of the eloquent eyes somehow posted bail and spent two more years in California dodging his potential jailors before eventually heading south, leaving no record that the trouble back east was a matter of concern or that the forgery arrest was something to take seriously. He presented himself as a patent-wielding inventor of the new manufacturing age, maintaining his self-presentation and the knockoff butter as legitimate, even as the public began to cast him as the disingenuous oleo man and a challenge to sincerity with a jury still out on the matter of legitimacy.

Paraf bounded onto a Gilded Age stage that was prepared to see him. His audience—his mark—was already wrestling with the problem of whether novelty was a change for the better or for the worse. He plied the uncertainty over fabrication and antagonized the search for authenticity.

Admittedly, the adulteration of foods, drinks, and drugs goes back at least as far as notices from the ancient Hittites (ca. 1500 BCE) and Roman legal codes and references in t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- A Note on the Digital Companion to This Book

- Table of Maps

- Prologue

- 1. THE APPEARANCE OF BEING EARNEST

- I. The Culture of Adulteration

- II. The Geography of Adulteration

- III. The Analysis of Adulteration

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index