![]()

CHAPTER 1

CHOICE

“I learned this, at least, by my experiment: that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours.”

—HENRY DAVID THOREAU

“The mark you make today will show up tomorrow.”

—UNCLE CLEVE

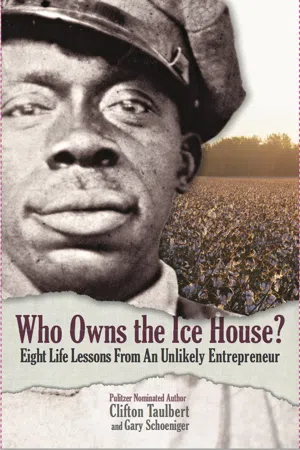

CLIFTON’S WORLD IN THE MISSISSIPPI DELTA

“Cliff! Go on and git up, boy! Git on outta that bed. The sun’s already up an workin.’ It’s time to wash up and git your food. You know, you cain’t be late for work. My brother-in-law, Cleve, won’t stand for that. I wuz talking to Cleve on Sunday while visiting him and my sister, Mae. That’s when he told me all ‘bout his decision to hire you.” Those were the words I heard early one morning in 1958, that day I partnered my young life with Uncle Cleve and his Ice House more than 50 years ago.

It still amazes me that a conversation and a job that happened so long ago could end up being so impactful on my life … even today. The picture is as clear in my memory as the day I heard my great aunt’s voice yelling out to me from the small kitchen and into my small bedroom. My new job and her commitment to my life came together to forever change my perspective of who I could become. Before I take you to the Ice House and to Uncle Cleve, I want you to understand what the world around me at the time was like so you can see just how fateful my job at the Ice House would become.

It was the summer of 1958 when Ma Ponk’s words pulled me off my small cot to get ready for work. It all happened so long ago, but it seems like yesterday when my mind travels back to Glen Allan, Mississippi, where I was born. It was a small cotton community, way off the main highway, with a population of less than 500 people, located on Lake Washington. Cotton fields stretched as far as one could see, both literally and figuratively.

Limitations, social, physical and emotional, were all around us.

Just thinking about my hometown brings back memories of the insufferable heat and humidity that were constant during the summer months and necessary for growing cotton. Even as a young boy, I recognized the extent to which cotton shaped our lives. I can remember when there was nothing else to do but sit on the top steps of my great-grandfather’s front porch and look out as far as I could see. I wanted to see something different, but all I could see was Greenfield, a plantation community just south of us, the same place I had seen all my life, with the same rows and rows of cotton that looked as if they would never end. Even then, that sight made me think that I was seeing the end of my world. Limitations, social, physical and emotional, were all around us.

I grew up during the time when cotton was still king, and our lives were defined by strict racial segregation. It was a restricted world with so many boundaries in place, that is until my great aunt entered my life. She took it upon herself to raise me, to make sure that I accomplished something useful. Until I met her, I lived in different homes with various relatives, starting with my great-grandparents. I had been born to a teenage mother and my future was uncertain—or certainly limited. That was until Ma Ponk altered the course of my life forever.

For Ma Ponk, teaching me to work hard was part of her commitment to my future. Working hard had brought her a measure of independence. She wanted the same for me—and more. Sleeping late was never tolerated; thus, the memory of her admonishment to “git up” still rings in my ears. I was only thirteen, but within our southern culture, I was man enough to do a full day’s work. Ma Ponk never had to call me twice. I was slow to move, but always up before she had to yell at me for the second time.

That morning in June 1958 seemed like a typical workday; however, it would turn out to be very, very different. I was going to work—but not to the cotton fields where I had been working for several years and where she, herself, would go that day. No, I would not be bending low in the hot sun from early morning to sunset, carefully weeding the young cotton plants—a process we called chopping. Uncle Cleve, Ma Ponk’s brother-in-law who owned the Ice House, had offered me the opportunity to work for the summer—that is, if my first few days worked out to his satisfaction.

I remember the day Uncle Cleve’s truck slowed down and stopped beside me. I was walking uptown, but he motioned for me to come over. “Clifton, I been watchin’ you. You got a good head on your shoulders. Ponk’s doing a good job in raisin’ you. I been giving this some thought. How ‘bout you coming to work for me? What you say, boy?”

I was dumbfounded that day, hardly mustering up the words I needed. “Yessir, yessir, Uncle Cleve! I’d really like that. I know I can do it.”

With his ever-present pipe in his hand, he opened the door of the truck and invited me closer, somewhat laughing, but not quite. “Now hold on, boy! The work is hard. You gotta git up early. You gotta be on time! I know young ‘uns like you. You like to sleep late. I ain’t havin’ none of that. I’m telling you now, if you late, more than two times, you cain’t work for me.”

I assured him that I could do it. He reached out and shook my hand just like I was a fully grown man. I remember smiling to myself and slowly walking away. I did look back once and I saw Uncle Cleve slowly driving his truck down the street and into his front yard, parking in the same place he always parked. I could hardly wait to get back home and tell Ma Ponk.

I was just another “field hand’” even though I was barely a teenager.

With my new job opportunity, I was ecstatic, and so was Ma Ponk. She was happy that her boy would no longer be a “field hand,” as we were commonly called. She wanted something better for me, and so she was determined that I would be on time. Uncle Cleve had a reputation for being on time and expecting the same of others. He made no exceptions. All throughout Glen Allan this was common knowledge. I was eager to start, and Ma Ponk was committed to making sure that I made a good first impression. “Boy, git outta that bed!” Those were her words that June morning that started my day and introduced me to a way of working and thinking that would forever shape my life. I will never forget that morning, the day I no longer had to catch Mr. Walter’s field truck as it headed out to the cotton fields with the field hands.

Mr. Walter’s truck had been picking up people for field work and taking them to surrounding plantations for years. Getting on his truck had become a shared way of life. This was what we did, continuing a system that was an outgrowth of slavery—the human labor force needed to support the massive plantation systems in the south. When I came of age to chop cotton, it was no different for me. Mr. Walter’s truck showed up without fail. Ma Ponk and I were among his faithful customers. We knew to get up early before the sun rose to be ready when Mr. Walter’s truck turned the corner by the colored school. Without fail, during those hot summer months, we would be waiting for him by the front gate. He never had to wait for us. Fortunately, Ma Ponk was a “mother” in the local church and as such was treated with respect. Mr. Walter always saved a place for her in the cab of the truck, but not for me. I was just another “field hand’” even though I was barely a teenager.

I had to crawl onto the back of the truck and fend for myself as I looked for a place to squeeze in. It never failed; I always stepped on somebody’s foot or elbowed someone in the chest while trying to find myself a place to fit. “Boy, cain’t you see? Git yourself some specks.” I’d get the talk, but never a smack. After a while, the feelings would cool down, and we’d be on our way to the next stop. Laughter, jokes, and conversations I should not have heard at my young age soon filled the back of the truck. We were on our way, packed together like sardines in a can, so close that our steaming breath intermingled in the cold morning air. After several more stops, we finally made it to the fields where we would be given sharpened hoes and assigned cotton rows to weed. We never had to worry or think about when to start work because a whistle would blow or we’d hear Mr. Walter’s loud voice telling us it was starting time.

“Alright, all of y’all, wake up. Git on wid it. Git yore rows. Jim, git yore water buckets ready, and be careful, don’t waste my ice.”

Nothing was required of us except muscles and time—no thinking, no planning, no creativity—just the rhythms of tending to cotton that had been part of Delta life for generations.

Knowing it was time to start, we would let our laughter die down, and the adults got really serious about the only work many of them had ever known. It was no different for me. I also knew it was time to become serious. With my row assigned, I would bend low, as I had been taught to do, and carefully look for weeds to cull out that were hiding among the young plants. This would be our backbreaking routine for the next ten hours. This was our way of life. Except for a precious few, all of the people in our small community made their living from doing field work. Nothing was required of us except muscles and time—no thinking, no planning, no creativity—just the rhythms of tending to cotton that had been part of Delta life for generations.

However, that hot day in June, I broke with tradition. I did not catch Mr. Walter’s truck. I had a job. Working in the fields was never called a job. It was just what we had to do. Upon hearing of my great luck, the older people who knew me expressed their pride and their expectations. “That’ll be good for the boy. Cleve’ll teach him sumpin.’ Sho’ hope he can hold out, though.” My being able to leave the fields boded well with them, but they knew Uncle Cleve’s reputation for hard work. Some of my young friends teased me about my job because Uncle Cleve was known as a no-nonsense man—a man who barely ever smiled. I didn’t care. I wanted that job. I was tired of field work. I never wanted to earn that admired reputation of chopping more rows than anyone else. I never wanted to learn how to sharpen my own hoe. Even though I was born into that world, I always wanted something better. I didn’t know what better would look like; I just knew that I wanted something different. The problem was that “better” jobs were virtually nonexistent—that is until the job at the Ice House opened up for me. I couldn’t wait to be out of the scorching sun. For me, Uncle Cleve’s reputation as something of a taskmaster was no impediment. Hard work didn’t scare me. Ma Ponk had raised me, after all. She even made up work for me to do when none really existed. No matter how hard or no-nonsense he may have been, working for Uncle Cleve in the Ice House had to be much better than the fields.

He lived in our neighborhood and was subject to the same social restrictions as the rest of us.

I don’t know much about Uncle Cleve’s early life, where he was born, or about the personal hardships that he may have encountered along the way. I just knew he came from Coldwater, Mississippi. I am sure, though, that he never went beyond grade school, if that. Even so, he could read, write, and count, and he possessed an incredible memory. All of this and more came to light as I spent time in his presence. Later, I would learn that nothing could get past him. Yet, apart from owning the Ice House, he was one of us. He lived in our neighborhood and was subject to the same social restrictions as the rest of us. He had no special gifts. He had no access to wealth. He was not related to special people, but he stood out from all of us. In our world where over 90 percent of our adult population worked in the cotton fields, he was among the few who dared to count his own dream as worthy of being pursued.

He was among the few who dared to count his own dream as worthy of being pursued.

I always quietly admired Uncle Cleve. His courage and determination did not go unnoticed. Nearly everybody in our community called him Mister Cleve. I had taken notice of that. And he was respected. Just like us, he got up early every workday, before the sun rose, and went to bed late—but the difference was that he was doing it for himself. He was his own boss. He paced everything, even his driving. He always drove the speed limit or below it. I can still see him in his 1947 International pickup truck slowly backing out of his drive onto the gravel road that would take him to the Ice House. Some of the townsfolk laughed at his slow driving, but he never got into a wreck, and he always made it to his destination on time.

I thought he even walked differently than the rest of us. Uncle Cleve held his head slightly to the side as he ambled at his own pace, his ever-present pipe clenched between his teeth. He may have walked slowly, too, but he always looked as if he had somewhere important to go. Not only was he respected, he was also respectful. During the time when most of the adults in my community were being undervalued, Uncle Cleve’s value of himself was shared among us. He always tipped his hat to the ladies and nodded at the men he knew, careful not to use language that was inappropriate. His confidence and the way he carried himself even impacted the white community’s response to him. His actions defied stereotypes and so earned him a measure of respect, and whatever encounters there may have been were civil. While other men of his age were hanging out, getting involved in baseball, and making serious visits to one or two of the juke joints in Glen Allan, Uncle Cleve spent his time reading books, working on cars in his garage, or repairing one of his rental houses. Yes, this short, stocky, dark-skinned man who barely smiled and who was always working became a hero to me long before I went to work for him.

Sunday was our day off with many of my afternoons spent at Uncle Cleve’s and Ma Mae’s modest home. Uncle Cleve had this big chair in the front room that had everything he needed at his fingertips, his paper, his glasses, his can of Prince Albert Tobacco, and a cup of coffee, black, with no sugar. “Hey boy, whatcha doin’ for yourself? Mae, you got somethin’ for the boy to nibble on back there? Boy, you gittin’ big. Still working everday when you ain’t in school? Work is good fer you, course you know that. It keeps you outta trouble. You staying out of trouble, ain’t you?”

“Yessir,” I managed to utter. And before I could say anything else, he would be talking again.

“They’s plenty of trouble for young boys to git into ’round here, but I been watching you. Real proud of the way you carry yourself. Ponk say you doin’ good in yore studies. Keep it up. You gotta do right early and then keep it up. Sho wish I had your chances, boy, no telling what I could do.” He looked so smart, all leaned back in the big chair and with the smell of his tobacco filling the room. I was captivated to say the least.

I was a young boy, but I admired his sense of independence, which seemed so different from many of the people I knew and loved. His conversation was always about being successful. He was one to always bring my schooling into the conversation. He made education an important topic. He always took time to ask me important questions about the world around me. Even before I went to work for him I wanted to be like him. Just watching him, I was unsure of how this could happen. However, once I started at the Ice House, this would all change. My excitement about working for a boss that looked like me was huge.

Glen Allan had not changed in a hundred years. Segregation was still the law of the land. Mr. Walter’s field truck still picked up the field hands. But my world had changed. In the crowded cab of Uncle Cleve’s pickup truck or on the days when the two of us talked while sitting on the bench of the Ice House porch, my thinking began to shift. While cutting and lifting blocks of ice and sweating profusely in the process, I learned to expect more of myself. Being in the presence of Uncle Cleve and observing the way he carried himself on a daily basis provided me a different set of lens through which to view my own life and potential.

Uncle Cleve refused to let his environment dictate his response to his life and his dreams—which was harder to do than not. Looking back, I know that he intentionally chose how he would respond to his circumstances. His life was his choice. There is little doubt that his background and his environment influenced his life, but he did not allow it to determine the outcome. He chose differently. He knew he was black, but he also knew that his life mattered. It seems as if owning the Ice House provided him the necessary courage to venture even further in the world of business. By the standards of that day, he wasn’t supposed to do any of this. Yet he continued to reach for the next step on the ladder. I saw him reach with my own eyes. It was amazing to me then, and even more so now that I realize the difficulty he faced because of the times in which he lived. All this must have given him a tremendous sense of personal pride, but he never wore it on his sleeve. He had that slight smile that seemed to indicate he knew something no one else knew, that he had a secret. But it was no secret that Uncle Cleve was all about his customers. He never forgot that the Ice House and his other businesses depended upon them. I learned from him to keep my priorities straight: The customer always came first. His actions were powerful lessons.

I was a young boy, but I admired his sense of independence, which seemed so different from many of the people I knew and loved. His conversation was always about being successful.

Cleve Mormon had stepped beyond what was expected of the people within our community. He showed me what was possible. Over time, I began to understand that I could do no less. My future became important to me. Although for four years I had to travel more than 100 miles round trip each day to high school, I graduated as valedictorian and with a perfect attendance record. Getting up to make the trip to school each day and working hard to get good grades was not difficult for me. While at the Ice House, I had seen the value of working hard. I realized that my life mattered. I could add value to the life of others by making sure my life had value.

The day Uncle Cleve hired me was one of the mile...