But not everyone sounded so dismal. U.S. senator John Stennis believed there was a “good chance” that the Court would issue “fairly liberal ground rules” by which white and black southerners could work out a plan. Stennis felt that intemperate outbursts weakened white southerners’ position nationally and only inflamed resentments among blacks back home. Stennis’s critique of Georgia governor Herman Talmadge applied equally well to intemperate leaders in his own state: “It seems to me that Governor Talmadge is making a severe mistake in advertising his non-compliance with the Supreme Court decision, making it a crusade of defiance.” Stennis knew that white leaders in Mississippi were not going to integrate the public schools, but he also knew that “the less we advertise this the better.” Stennis advocated compromise with local black leaders. In return for a pledge not to bring desegregation lawsuits, white leaders would ensure that blacks received “adequate and equal” schools—in other words, the kind of schools that the law had actually required southern states to offer since the Plessy decision. Stennis contacted prominent young whites he believed would keep a cool head in the current crisis. He hoped to form a network of practical-minded leaders who could operate on a word-of-mouth basis, refraining from formal declarations of defiance and quietly managing the school crisis—and maintaining segregation—at the local level for “15 or 20 or 25 years.”2

Stennis and others understood implicitly what recent historians of the Jim Crow South have emphasized—that white supremacy could not be imposed unilaterally on southern blacks, that it was the result of countless negotiations, and it was rife with contingencies and compromises.3 In Mississippi, these leaders called their strategy “practical segregation” to distinguish it from the impractical plans of the Citizens’ Council. Whereas hard-line segregationists in the Citizens’ Council offered emotional pledges of defiance and defended even the smallest form of racial segregation, practical segregationists advocated realistic approaches that tried to maintain good relations with local African Americans and minimize outside attention and federal interference. These leaders also attempted to balance an increasingly desperate fight to preserve state-sponsored segregation with other concerns for Mississippi’s industrial and political development. This did not make them “weak” segregationists, as hard-liners charged. In fact, they were much more successful in actually preserving segregation than were most hard-liners because they understood that outright defiance was hopeless. They advocated reasonable, peaceful measures because they knew it was the only way to have some stake in controlling where, when, and how desegregation would actually occur.4

J. P. COLEMAN AND THE CITIZENS’ COUNCIL

It was the goal of practical segregationists to keep racial struggles out of the public eye. It is not surprising, then, that they have received less attention from scholars, particularly in Mississippi, the state with the most militantly reactionary segregationist movement. Four days after the Supreme Court issued its decision in the Brown case, Judge Tom P. Brady, a key figure in the origins of the Citizens’ Council, finished the second of two letters that he dashed off to Mississippi Speaker of the House Walter Sillers. In it, Brady envisioned a new political movement that would “cut across all factors, political groups and embody leaders in every clique. . . . All white men in every walk of life must be mustered out. It must be made their fight. If the southern states do not unify in thought and action the NAACP will emerge victorious.” Brady and other Citizens’ Council founders imagined a modern activist organization protecting white supremacy. It was, in their minds, a counter to what African Americans had in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)—an organization dedicated expressly to protecting their interests as white conservative southerners, a group that South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond characterized as “the greatest minority in this Nation.”5

The resistance movement had many parts, none more important than the Citizens’ Council, the organization born in the small Mississippi Delta town of Indianola in 1954. The group grew out of conversations that Robert Patterson, the manager of a cotton compress and a former paratrooper in World War II, had with a local Harvard-educated attorney and a prominent Indianola banker. Patterson called a meeting for July 11 with fourteen business and professional men to form an organization “to counteract the NAACP and the other left-wing organizations which . . . had certainly contributed to the Black Monday decision.” The group included the Indianola mayor and the city attorney. A public meeting of seventy-five to one hundred townspeople followed, and the Indianola Citizens’ Council was born.6

Following the “Indianola Plan,” other Mississippi towns organized their own chapters. Members of the Mississippi legislature flocked to the organization. By October 1956, the Association of Citizens’ Councils in Mississippi claimed a membership of eighty thousand, though more sober estimates placed the number at around fifty-five thousand. Council membership boomed not just in the Black Belt but also where the local African American community aggressively challenged existing segregation laws. When Gulf Coast blacks attempted to integrate Mississippi beaches, for example, whites in Harrison County successfully organized around the slogan “White Solidarity Means White Beaches.”7

Over the course of the 1950s, the febrile efforts of the Citizens’ Council turned Mississippi into the heart and soul of organized resistance to desegregation. From the Citizens’ Council’s founding in 1954 through the council-orchestrated showdown with the federal government during the Meredith crisis, the organization, in effect, “closed” Mississippi. They policed a white racial authoritarianism that ran roughshod over the civil and political rights of both white and black Mississippians. Because of the council’s influence, no place in the United States in these years came closer to resembling the repressiveness of apartheid South Africa than did Mississippi. One journalist compared the Citizens’ Council’s power in the state to the “role played by the Nazi party in Germany and now played by the Communist party in Russia.” A series of five articles by journalist James Desmond in late 1955 reported that the “thought control” the council exerted was “a monstrous cloud blotting out nearly all dissent.” Hodding Carter III concurred, “The Citizens’ Council as of January, 1958, stands virtually unquestioned in its dominance of the white community in Mississippi.”8

As domineering as the Citizens’ Council was, however, fault lines existed in Mississippi’s white community, and it is important to trace them. An important one in the late 1950s ran straight to the governor’s mansion. James P. Coleman, who served as governor from 1956 to 1960, had a contentious relationship with Citizens’ Council leaders. He coined the phrase “practical segregation” to distinguish his own approach from that of the council. Coleman called for “cool, clear thinking on racial problems,” drawing an implicit comparison with the bombast of the Citizens’ Council. Coleman’s pragmatic cast of mind hardly meant that he was soft on segregation, though that was the implication of Citizens’ Council leader Judge Tom Brady when he derisively referred to Coleman as “fair-minded Jim.” Coleman never wavered in his defense of segregated schools. He predicted fifty years or more would pass before southern schools would willingly desegregate—“certainly not in my lifetime,” he vowed. A form letter Coleman sent to constituents in the fall of 1956 reiterated his commitment to segregation: “I must, and will, without fail, maintain the segregation of the races in our state.” When he ran for a second term as governor in 1963 (Mississippi law at the time forbade a candidate from two consecutive terms), he proudly did so on a record that no significant integration came to Mississippi during his watch.9

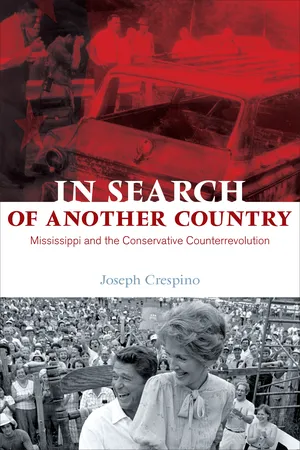

Figure 1.1. J. P. Coleman being sworn in as governor, January 1956. Former governor Hugh L. White is at right with cane. Coleman pledged that during his administration “the color line won’t break—or bend.” His low-key, pragmatic approach to guarding the color line was more effective in actually preserving segregation than the intemperate efforts of the Citizens’ Council.

Coleman, however, was mindful of how the segregation fight impinged on other political priorities. One such issue was the goal of maintaining Mississippi’s and the South’s role within a viable Democratic Party. Coleman had shown keen interest in national Democratic Party politics since his earliest days as a political aide in Washington, where he campaigned for control of the Junior Congress, a political organization for Washington aides, against another young aspiring southern politico, Lyndon Johnson. The early competition turned into a friendship that eventually led to Coleman’s appointment to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in 1965. After Mississippi’s Dixiecrat revolt in 1948, Coleman battled at the 1952 and 1956 Democratic National Conventions to keep a wavering Mississippi delegation in line with the national platform. The national party aided loyal southerners like Coleman by limiting the reach of the Democratic Party platforms on civil rights during the 1950s.10

Near the end of his administration, Coleman exasperated segregationist hard-liners by immediately calling in the FBI to investigate the lynching of Mack Charles Parker in south Mississippi. Mississippi law prohibited Coleman from running for reelection in 1959, but even if he had, he would have faced strong if not insurmountable opposition from hardliners. Tom Brady, considering a run for governor himself in 1959, branded Coleman “the leader of the Dixiecrat moderates.” Brady pledged to combat the “foot in the door” that desegregation forces had gained in the state during Coleman’s watch.11

Coleman saw Citizens’ Council leaders and other last-ditch segregationists as political insurgents who were willing to provoke white Mississippi’s worst fears of racial integration to advance their own political interests. While still governor-elect, Coleman made clear his opposition to the council-backed drive to pass a resolution of nullification against the Brown decision, a measure he described as “legal poppycock.” Coleman turned to James Silver, a friend and expert on Civil War history, and the moderate congressman Frank Smith, who represented the Delta, for help in researching the history of nullification efforts. Smith passed on research gleaned from the Library of Congress. The Citizens’ Council had endorsed nullification in its newspaper, and prominent council supporters such as Tom Brady, John Bell Williams, and James Eastland were in favor of the initiative. In an open letter to the Mississippi legislature, however, Coleman expressed dismay at the proposal and its supporters: “History teaches in a long succession of events that such efforts have always failed, and in failing have brought down terrible penalties upon the heads of those who attempted it.” Coleman believed that politicians like Brady, Williams, and Eastland were “trying to grab headlines” and, in the process, weakening the segregationist fight.12

The Citizens’ Council was well aware of Coleman’s cool attitude toward their brand of resistance. In May, Coleman admitted to reporters that he intentionally avoided a Citizens’ Council gathering in Jackson at which several state political leaders spoke. Coleman claimed he wanted to be in a position to speak for “all the people and not any special group.” The State Executive Committee of the Citizens’ Council tried to use the 1956 presidential election to test Coleman’s support among white Mississippians. The committee circulated a resolution among all county Democratic organizations that would have bound the state’s delegation to vote only for candidates in accord with Mississippi’s resolution nullifying the Supreme Court’s Brown decision. Knowing that such a plan would render Mississippi’s delegate votes meaningless, Coleman agreed to support a resolution that merely restated Mississippi’s principles, leaving the delegation unbound. Coleman emerged the clear victor in this fight as the county Democratic organizations voted overwhelmingly to support his position.13

It was exactly because of the skepticism of prominent Mississippi officials like Coleman that Citizens’ Council leaders worked so hard to portray their organization as the voice of respectable, middle-class whites. The organization had “an almost self-conscious desire for respectability,” David Halberstam noted in a 1955 profile on the council. Citizens’ Council leaders in Mississippi were concerned that with the Supreme Court’s school decision, “the wrong crowd”—meaning violence-prone, working-class whites—would take the lead in the fight against school desegregation. Council leaders associated the Ku Klux Klan with lower-class violence and lawlessness. “None of you men look like Ku Kluxers to me,” Tom Brady told an Indianola audience in October 1954. “I wouldn’t join a Ku Klux—I didn’t join it—because they hid their faces; because they did things that you and I wouldn’t approve of.” Robert Patterson warned in a 1954 form letter to supporters that if “our highest type of citizenship fails to supply a plan to maintain segregation and the integrity of the white race, then the wrong crowd will supply the leadership and there will be violence and bloodshed.”14

As part of its modern, professional approach to white supremacy, the Citizens’ Council developed a regular publication, the Citizen’s Council, later renamed the Citizen, and would develop the Citizens’ Council Forum film series, a public interest talk show. Familiar southern segregationist politicians, many of them from Mississippi, dominated the list of Forum guests, but the roster also included Barry Goldwater, John Tower, and conservative representatives from Iowa, Indiana, Michigan, and California. In Jackson, the state capital and lone urban center, the Citizens’ Council targeted middle-class neighborhoods to conduct door-to-door “‘Freedom of Choice’ surveys” in which council representatives tried “to learn the sentiments of all local citizens on the question of racial segregation in schools and residential areas.” These efforts were more recruitment drives than they were actual surveys; given the larger a...