eBook - ePub

The Linguistic Landscape of the Mediterranean

French and Italian Coastal Cities

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Linguistic Landscape of the Mediterranean

French and Italian Coastal Cities

About this book

This book explores the Linguistic Landscapes of ten French and Italian Mediterranean coastal cities. The authors address the national languages, the regional languages and dialects, migrant languages, and the English language, as they collectively mark the public space.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Linguistic Landscape of the Mediterranean by Stefania Tufi,Robert J. Blackwood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Sketching the Contexts: Italy and France

Introduction

The main aim of this chapter is to provide an overview of language change and language management in Italy and France in order to situate the competing factors and actors which are responsible for the linguistic construction of the respective public spaces. In the course of the discussion we shall highlight aspects ranging from political-ideological discourses to socio-economic developments and their interconnections. Language policy will be analysed in its broadest possible framework (Spolsky, 2004) to give an indication of the complexity and rootedness of language ideologies, and of how they impact on language practices. We are aware that we merely touch upon a number of fundamental issues and debates revolving around the linguistic histories of the two countries, but the intention is to bring to the fore similarities and differences between the two contexts in order to provide a setting for subsequent chapters.

One of the principal structural differences between Italy and France is due to the organizational models which defined their composition and which are rooted in the Middle Ages. On the one hand, Italy, and primarily northern and central Italy, was characterized by polycentric structures based on city-states which enjoyed political and economic autonomy; France, on the other hand, was from the outset an example of a ‘primacy organization’ (Salone, 2005) controlled by a major capital city, Paris. In spite of this major constitutive difference and of the diverging modalities in the development of language policy, it will become apparent that both countries were immersed in the philosophies and aesthetic principles promoted by the European elites since the early modern period. To mention one aspect, linguistic purism is considered to have been articulated for the first time by the Italian Accademia della Crusca (founded in 1583) and following the codification of a literary canon in 1525. This type of ideology was rooted in classical ideals inherited by the fifteenth century humanists and looked to literary models, and predominantly poetic production, along the lines of what had constituted the models for poetry and prose in Latin in the classical world (Marazzini, 2004). This profoundly conservative attitude on the part of cultural elites was therefore firmly anchored in the past and in rigid social organizations characterized by exclusive practices carried out in exclusive languages. Vernacular interpretations and perceptions of linguistic purity and beauty are the result of internalized aesthetic discourses which were fixed in works such as Pietro Bembo’s Prose della volgar lingua, which included a normative grammar of Italian. In Bourdieian terms (Bourdieu, 1986), it could be argued that Bembo produced an ante-litteram theory of linguistic taste and social distinction. In this sense, perceptions of the aesthetic value of languages are a result of enculturation processes, and they have generated hegemonic discourses which cross over national boundaries. The linguistic histories of both Italian and French bear witness to this phenomenon.

Italy – polycentrism and linguistic diversity

The lack of a unitary state and the emergence of a mercantile class which extended its linguistic practices, that is the use of local vernaculars, to written domains are usually indicated as the beginning of linguistic polycentrism on the Italian peninsula (Petrucci, 1994). This gave rise to distinct literary traditions which, where supported by influential cities, gained remarkable prestige, as will become apparent over the course of the book. The sense of independence and autonomy of the numerous political entities represented a challenge both during and after the formation of the Italian nation-state in 1861. The implementation of a highly centralized system at this juncture was primarily a legacy of the Franco-Piedmontese style of administration, but was also guided by the awareness of the vulnerability of the new national entity. As a result, federalist ideas of state administration were rejected in the name of unity (Mack Smith, 1997). However, the town/city and its surrounding area, and sometimes a pre-existing state, continued to represent a strong element of belonging and identity (Lyttleton, 1996).

The above issues are closely linked to the question of national unity and national identity, which has been the subject of much academic writing on Italy.1 The Risorgmento itself, that is the social, cultural and political movement that led to Italian unification, never ceases to be an object of interest on the part of Italian and international scholars and observers alike (Patriarca and Riall, 2011). Discourses of a divided history have therefore permeated constructions of Italy at all levels and, amongst other aspects, they have nourished recent regionalist claims and demands for local autonomy since the 1970s. Although the Italian Constitution (1948) had sanctioned the introduction of regional authorities in their current form, the 20 Italian regional governments did not come into existence until 1970 and administrative devolution came into effect in 1997 with the law of 15 March 1997/59. It can be argued that the enactment of the constitutional principle of regional autonomy provided the institutional background to subsequent regionalist movements such as the Lombard/Northern League. Indirectly, and before the establishment of European agendas, the Constitution represented a move towards recognizing and complying with the plural nature of Italian society.

Italian polycentrism is arguably most evident in language matters. Urban centres have often provided linguistic models and promoted processes of koineization in wider areas, therefore consolidating a type of linguistic diversity which is unparalleled within Europe (De Mauro, 1963). The linguistic relationship between centre and periphery has not been a smooth one. The literary prestige acquired by the Florentine vernacular via the works of Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio guaranteed the establishment of a linguistic model as early as the fourteenth century. This vernacular was codified in 1525 via Bembo’s Prose della vulgar lingua and continued to be used in literary production, but its use was limited to a small elite. The vernacular started being used alongside Latin in formal education in the late sixteenth century, and the publication of the Vocabolario della Crusca (1612) sanctioned normative Italian as an object of study via learning tools (De Blasi, 1993). It was only after unification in 1861 that increasing masses of Italians were exposed to a language which was to fulfil public functions as a natural consequence of its consolidated role of language of culture. At that stage, and via diverse sections of the population, Italian came into contact with numerous local varieties, some of which had prestigious literary traditions and which had been in use in the former capitals of independent states and kingdoms (including Naples, Palermo, Genoa, Venice, and others) (Marazzini, 2004).

The term dialetto (dialect) in the Italo-Romance context started appearing after the codification of the literary language, and stood in opposition to lingua (language) precisely because of the lack of characteristics such as standardization that make a linguistic variety a language. Given that Italy’s dialects are the continuation of varieties deriving from Latin, they are not dialects of Italian, but parallel developments (Maiden and Parry, 1997). As a result, and unlike anglophone environments, the dialects of Italy can be structurally very different from Italian and their lower status is due to extra-linguistic factors. They represented the main means of (oral) communication for Italians until recent times and have traditionally been relegated to the private sphere. Italian and local varieties have, since unification, coexisted, and featured in individual and community repertoires to varying degrees and with different communicative functions. After unification, the Piedmontese administrative model was extended to the rest of the Italy, but the Piedmontese kings did not impose their idiom upon the country. Amongst many regional differences, Tuscan Italian was the de facto national language insofar as it had contributed to the construction of a common cultural heritage. Florence was therefore to remain the linguistic capital, while the political capital would be Rome after the end of the papacy’s temporal power in 1870.

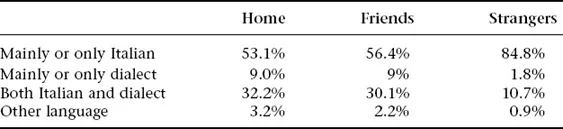

Italy is therefore a linguistically diverse country, one where history and geography have played fundamental roles in the shaping and development of myriad language varieties. Against a backdrop of nineteenth-century linguistic nationalism, and from an external perspective, Italy was a non-nation in so far as it lacked a common language to articulate its nation-ness. Alternative accounts highlight the unsuitability of this model for Italy and maintain, for instance, that it is not necessarily one language that confers linguistic identity to a nation, but it is the nation’s linguistic heritage as a whole. From this perspective, and due to the richness and plurality of its expression, Italy could be considered to be an ultra-nation (La Fauci, 2010). Italo-Romance dialects continue to be used to this day and a recent survey (ISTAT, 2014a) confirmed trends already highlighted in previous investigations: even though exclusive use of the dialect continues to decline, and it is now employed with ‘strangers’ only by a small minority, about 30 per cent of respondents declared that in the home and with friends they normally employ a dialect alongside Italian (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Language practices in contemporary Italy: Italian/dialect use

Source: ISTAT, 2014a.

This is partly a consequence of the fact that the spread of Italian occurred at an accelerated pace only after the Second World War and due to socio-economic factors such as urbanization, extended state education, and mass consumption of television programmes (De Mauro, 2014). From a disciplinary perspective, this explains the central role of the concept of language repertoires in discussions about language practices in Italian linguistic studies, a legacy of Italian dialectology as it developed in the nineteenth century (Grassi et al., 1997). Leaving aside spatial variation, of which all Italians are aware (Cini and Regis, 2002) and which contributes to complex linguistic repertoires, Berruto (1987) outlined the architecture of contemporary Italian as a result of three intersecting axes which account for variation on a diastratic, diaphasic, and diamesic level. In other words, an observation of the interplay of factors such as social group, context, and medium allows us to interpret language behaviour along the continua of language variation. Discrete categories of types of Italian including regional, colloquial, and standard are labels of convenience to be applied to spoken realizations of the national language, which have progressively become more fluid as ever increasing masses of people have had access to and mastered Italian. This has in turn brought about processes of re-standardization of Italian which have produced neo-standard Italian (Berruto, 1987), a consequence of the relaxation of the normative stance dominating written practices. Simultaneously, contact phenomena have affected both dialects, which have become Italianized to a certain extent, and Italian, which is always characterized by regional elements in oral production.

The articulation of both individual and group biographies would be impossible without reference to the set of language varieties that Italians can draw upon in everyday communication and that are constitutive elements of local and group identities. National history would not be complete without an understanding of Italy as a diglossic country at the time of unification and its long transition to bi- or multilingualism and dilalia (Berruto, 1987), a concept developed to represent current practices whereby Italian has progressively entered domains which were entirely dominated by dialects until not long ago.

In this context, the eventual disappearance of dialects has been debated since Pasolini, a leading film-maker, poet, and intellectual of the twentieth century, introduced his thesis in 1964 (Pasolini, 1971). In fact, dialects maintain a high degree of vitality in Italy, as recent surveys show. Geographical differences in terms of usage persist, and both context and interlocutor remain significant variables in language behaviour. The current configuration of linguistic repertoires is rather complex because dialectal varieties and varieties of Italian have multiplied as a result of ever larger masses of Italians being brought up speaking and being educated in Italian on the one hand, and non-standard varieties incorporating standard expressions which make them viable means of communication on the other. Effective bi- or plurilingualism has led to new dialectal uses and users and to the widespread practice of code-switching and code-mixing. In addition to its oral uses, the dialect is being employed for a variety of functions which range from literary production to rap lyrics, and from advertising to social media. An aspect that is being constantly emphasized by the surveys is that these uses cut across social groups (ISTAT, 2014a).2 This explains the multifaceted contribution of dialects to the construction of the public space as testified by the case studies discussed in this book. This also explains that, although Italian is indisputably the dominant language in public environments, the Italian LL has been characteristically and increasingly multilingual insofar as new language actors have also contributed to the construction of the public space. An outline of language policy and its peculiarities will provide a context for an understanding of different degrees of participation in processes of place-making and -marking.

Language policy in Italy

Elsewhere, we have used the term non-policies with respect to institutional measures (or lack thereof) aimed at the spread and consolidation of the national language (Blackwood and Tufi, 2012). This definition rests on evidence provided by existing scholarship on the topic (De Mauro, 1963; Tosi, 2008; Orioles, 2011) and highlights the lack of a systematic approach to the implementation of a planned and thorough spread of the common language via institutional channels. Given that at the time of unification Italian was primarily a written reality, a significant channel to guarantee regular contact with Italian would have been state education (two years of compulsory schooling in 1861 which was increased to five in 1887 – see Gensini (2005)). However, instruction in a language which was effectively foreign for the vast majority of pupils in the nineteenth century would not have caused a shift to Italian on its own, had the population not been through radical socio-economic changes which accelerated processes of Italianization significantly only in the second half of the twentieth century. As a result, language policy cannot be meaningfully assessed without taking into account issues of literacy and the development of state education. From this perspective, it could be argued that in Italy institutional language policy was mostly covert (Shohamy, 2006), but pursued via education, which is one of the main forces in language management (Spolsky, 2009). It can also be argued that it was mostly education practices (Spolsky, 2004) which were involved in the dissemination and consolidation of language ideology.

It has been variously estimated that, at the time of unification, between 2.5 per cent (De Mauro, 1963) and 10 per cent (Castellani, 1982) of the population could speak Italian. These estimates are based on literacy rates and therefore, before we could rely on systematic surveys on language use, the only way to account for Italian speakers (or users) was to look at improvements in education provision. At the end of the nineteenth century, illiteracy was still widespread (40 per cent), but this is understandable in a context where compulsory education was of five years in 1877 and was increased to age 12 in 1905 (Gensini, 2005). In addition, problems relating to the actual implementation of compulsory schooling were at times insurmountable, and ranged from insufficiency of infrastructure on the one hand to open hostility from families who needed children for labour on the other – phenomena witnessed as widely in France as in Italy at this time. At this stage institutional, directed language policy can primarily be identified within the educational policies which promoted Italian both as the language of instruction and as an object of study. In this respect, the impact of schooling was significant and lasting insofar as the teaching of Italian emphasized prescriptive and normative uses of the language, and the pupils’ production was heavily sanctioned because, inevitably, it carried strong dialectal features that needed to be eradicated.

Although national syllabi and methods incorporated what could be defined as a punitive approach to language teaching from the outset, it is customary to single out fascist language policies in terms of clear and directed legislation introduced to regulate language matters. Raffaelli (1983) highlights, however, that there is a tendency to view fascist language policies in isolation, whereas purist if not openly xenophobic tendencies can be identified in the nineteenth century as well. They were the legacy of the Jacobin principle whereby language matters can and should be regulated, even though this entails the use of authoritarian methods. The first law regulating the language of commercial signs in unified Italy was in fact promulgated in 1874, admittedly for mainly fiscal purposes; foreign words were subjected to the payment of a higher tax than Italian words (Raffaelli, 1983, pp. 33–7). The fight against the use of foreign words on commercial signs became overtly political in the changed climate of the early twentieth century, when irredentist and nationalist groups appropriated the language issue for an anti-German campaign. The area around Lake Garda in the north of the country was the border between Italy and the Austro-Hungarian Empire at that time and it had been a holiday destination for high numbers of German-speaking tourists for years. Local businesses had been using German profusely on their commercial signs to accommodate the German tourists’ needs. As a result of the campaign promoted by the nationalists and with the support of the Dante Alighieri Society, local town councils introduced a series of measures to limit the presence of German on commercial signs. Interestingly, the symbolic use of the wider semiotic landscape also came to the fore and linguistic xenophobia was accompanied by architectural xenophobia. In the early twentieth century the debate extended to the management of the built environment, with open criticism of the ‘German style’ of the buildings erected in the area (Raffaelli, 1983, pp. 86–9).

Although the nineteenth century was characterized by occasional official measures inspired by nationalistic ideals and a purist and aesthetic conception of language, this period established a tendency that was subsequently enhanced in pre-fascist times and finally taken to extremes under Mussolini’s rule. Fascist language policies have traditionally received much attention as they represent the only systematic attempt to regulate language use in Italy, at least in the public sphere (Klein, 1986; Foresti, 2003). The first decree-law 352 of 11 February 1923 was in fact about the introduction of a tax on insegne (in their specific meaning of signs in relation to shops or other commercial establishments) that included foreign words, one of the very first pieces of legislation introduced by Mussolini (quoted in Raffaelli, 1983, p. 6). Fascist policy concentrated on three main areas: foreign words were to be banned, Italian was to be imposed upon national minorities as part of a process of de-nationalization, and dialec...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- An Introduction to Mediterranean Linguistic Landscapes

- 1 Sketching the Contexts: Italy and France

- 2 The Linguistic Landscapes of the Ligurian Sea

- 3 Peripherality in the Border Areas: Trieste and Northern Catalonia

- 4 Insularity in the Linguistic Landscapes of Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica

- 5 Social Representations of Marseilles and Naples’ Linguistic Landscapes

- 6 Cosmopolitan Linguistic Landscapes of the Mediterranean

- 7 Conclusions: The Transformative Power of Emplaced Language

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index