eBook - ePub

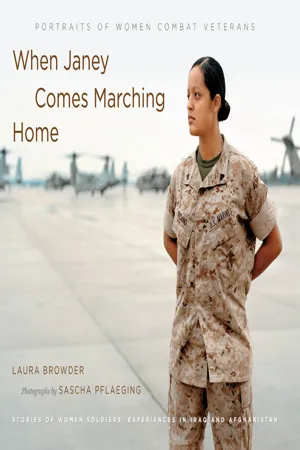

When Janey Comes Marching Home

Portraits of Women Combat Veterans

- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

While women are officially barred from combat in the American armed services, in the current war, where there are no front lines, the ban on combat is virtually meaningless. More than in any previous conflict in our history, American women are engaging with the enemy, suffering injuries, and even sacrificing their lives in the line of duty.

When Janey Comes Marching Home juxtaposes forty-eight photographs by Sascha Pflaeging with oral histories collected by Laura Browder to provide a dramatic portrait of women at war. Women from all five branches of the military share their stories here — stories that are by turns moving, comic, thought-provoking, and profound. Seeing their faces in stunning color photographic portraits and reading what they have to say about loss, comradeship, conflict, and hard choices will change the ways we think about women and war.

Serving in a combat zone is an all-encompassing experience that is transformative, life-defining, and difficult to leave behind. By coming face-to-face with women veterans, we who are outside that world can begin to get a sense of how the long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have shaped their lives and how their stories may ripple out and influence the experiences of all American women.

The book accompanies a photography exhibit of the same name opening May 1, 2010, at the Women in Military Service to America Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery, and continuing to travel around the country through 2011.

When Janey Comes Marching Home juxtaposes forty-eight photographs by Sascha Pflaeging with oral histories collected by Laura Browder to provide a dramatic portrait of women at war. Women from all five branches of the military share their stories here — stories that are by turns moving, comic, thought-provoking, and profound. Seeing their faces in stunning color photographic portraits and reading what they have to say about loss, comradeship, conflict, and hard choices will change the ways we think about women and war.

Serving in a combat zone is an all-encompassing experience that is transformative, life-defining, and difficult to leave behind. By coming face-to-face with women veterans, we who are outside that world can begin to get a sense of how the long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have shaped their lives and how their stories may ripple out and influence the experiences of all American women.

The book accompanies a photography exhibit of the same name opening May 1, 2010, at the Women in Military Service to America Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery, and continuing to travel around the country through 2011.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access When Janey Comes Marching Home by Laura Browder,Sascha Pflaeging in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Deployment

Deployments vary greatly in length from one branch of the service to the next, and even from one military occupational specialty (MOS) to another within the same branch. Although army deployments have stretched to fifteen months and even longer at different points in the war, marine and navy deployments are generally seven months long while airmen are deployed for four months.

What is notable about this war is not just the length of deployments, which have stretched to eighteen months for some soldiers, but also their frequency. For instance, Army Staff Sergeant Laweeda Blash has deployed three times to Iraq, and Army Staff Sergeant Shawntel Lotson was back for only seven months before deploying again.

Some women volunteer for deployments, and some do so frequently. After her first deployment to Iraq, Religious Program Specialist Second Class Rachel Doran, U.S. Navy Reserve, spent only two weeks back in the United States before heading to Djibouti, and then spent less than a month at home after her return from Africa before she went back to Iraq—a decision that did not sit well with her family.

As these stories make clear, there is nothing like a uniform deployment experience. Army Staff Sergeant Phyllis Magee-Lindsey, who arrived in Kuwait in the days shortly after the invasion, lived in an abandoned warehouse where she had to burn feces, eat MREs three times a day, and was unable to take a shower. Staff Sergeant Magee-Lindsey’s experience was very different from that of Army Sergeant Major Andrea Farmer, who was at Life Support Area Anaconda for her second deployment, where she had a twenty-four-hour PX, a movie theater with three daily screenings, a high-tech optometry clinic, a health clinic, five dining facilities, and indoor and outdoor swimming pools. Yet both women recalled the early days of the war, before IEDs became a common danger and many FOBs began to be mortared on a nightly basis, as being easier.

An MP who is outside the wire twelve hours a day will have had a very different experience from a machinist who never leaves her FOB. Soldiers who stayed in Kuwait for their entire deployments talked much more about discord within their units, and much less about the incredible camaraderie that developed. Yet taken together, these stories tell us a great deal about women troops’ daily lives in a war zone.

Lance Corporal Layla Martinez, U.S. Marine Corps

We landed in Kuwait. It was dark when we landed, we’re in giant buses and we have curtains covering the windows. I don’t even think it’s one feeling that you actually feel. You’re upset because you left your family. You’re excited. You’re mad. You’re happy. You’re everything all at once and you’re just waiting.

Sergeant Jocelyn Proano, U.S. Marine Corps

As soon as we landed, they gave us our ammo and we have to take a bus and cover all the windows so the insurgents won’t see us and they have to drive with the lights off and everything. That was kind of scary, so I’m thinking, “Oh my God, what’s gonna happen? What if we get hit? What if we have to run outside and start shooting and protecting ourselves? I really don’t want to go out this way—not even getting to my place of duty. God, please don’t let anything happen.” I was scared but at the time, I’m like, if this happens, I’m gonna shoot. I’m gonna start throwing grenades. I’m gonna to do what I was trained to do. I was G.I. Jane as soon as we landed in Kuwait.

The first night we got to Al Asad, what woke us up in the morning, we got hit—the fuel farm blew up. I think a mortar hit a fuel farm and it exploded. Smoke everywhere. And I wasn’t even scared—I was pretty excited. I was like, “Holy crap—we’re at war. This is gonna be good.”

Sergeant Kimberly Baptist, U.S. Army Reserve, Active Guard Reserve

We landed in Kuwait in the middle of the day. It was so hot because this was the end of August. The wind was blowing and it didn’t even feel like wind. It felt like a huge, hot hairdryer.

Master Gunnery Sergeant Constance Heinz, U.S. Marine Corps

The flight from Kuwait to Al Asad was on a C-130—piece of cake. The flight from Al Asad to Fallujah was on a forty-six, and halfway through the flight, I smell smoke, and I look over to the crew chief, and it just bursts into flames behind him. I’m sitting there in this helicopter with a half a dozen other people and we’re all realizing, “Damn, our bird’s on fire, I’ll be damned, I’m never even going to make it to Fallujah. I’m going to crash out here in the middle of the desert and never experience anything. This is it.” And then just as quickly as it started, the crew chief had everything under control and we just kept on going. Needless to say, when we landed in Fallujah, we were ready to get off that helicopter.

Sergeant Katharine Broome, Virginia Army National Guard

We were in Kuwait for about twelve hours and then we got onto a C-130 and flew straight into Al Asad. The C-130 did a combat landing. They want to stay out of range of the antiaircraft missiles, so they stay as high as they can for as long as you can and then fire roll down at a rapid rate, corkscrewing down onto the landing pad. When we woke up the next morning, we were in the middle of a sandstorm, so the world was orange. One of our executive officers came up to us and was like, “Welcome to Mars.” Just stepping outside, you would become covered in sand. The water smelled. You couldn’t open your eyes or your mouth when you took a shower. Yeah, it was Mars.

Staff Sergeant Phyllis Magee-Lindsey, U.S. Army

When we first arrived in Kuwait, I didn’t believe it, because it was fricking raining. It was so cold. I really felt like I was in the wrong place. And I was still thinking maybe they didn’t really take us to Iraq or Kuwait. Maybe they took us to someplace else. I just hoped it was a bad dream and I was gonna wake up and I’d be back in [Fort] Stewart and in my own bed, but it didn’t happen. Before we crossed over into Iraq, they told us that we needed to lock our weapons. I remember praying, “Oh Lord, just keep me safe, I gotta get back to raise my boys.” When we finally got there, it was about 6:00 A.M. I looked out the window, and I saw all of these tanks. And I saw American soldiers, and they were drinking soda. I felt safe because I knew that those guys had gone through there and they had cleared the way for us to come. It was okay then.

Sergeant Paigh Bumgarner, Virginia Army National Guard, Retired

When we pulled into Iraq, it was at night. Everyone was getting off the plane and there was a company waiting to get on the plane and they were like, “Next stop, USA,” and I was like, “God! This is going to be a long year.” I remember being really shocked that they had street lights and paved roads—because we were on Balad, which is huge—and huge buildings. We get to these little wooden huts where we’d be staying that leaked on us all night, because it was during the rainy season, which wasn’t any fun. And then we had our first mortar attack.

When we heard the first mortars hit and we could hear the sirens on post, that’s when it really sunk in for me.

Airman Victoria Hager, U.S. Coast Guard

Especially with us being in the Coast Guard, a lot of people don’t know that we’re over there. Prior to going out there, it looked like a vacation spot. Really, that’s how they advertised it to us. Where we’re going to live, what our work was going to be like. We were going to go out there, be on a boat—a little cruise—and then we’re going to come back to a suite and never be bothered. You’re going to have these long in-ports, you’re going to have everything there. And I was like, “Yes! I’m going on a boat. I’m getting more money.” It was just great. I was in my own little world. I got there—bam.

After a fourteen to seventeen hour flight, we got to Bahrain and we walked off the plane into the airport, and it’s kind of weird. You’re looking for the one or two people that are supposed to be picking you up. You don’t know where to go. You don’t know anything. Everything just hits you all at once. You just kind of look at each other like, “Wow. We’re here.” At the time, we flew commercial. We all came over at different times in little groups of people per boat and we slowly filtered in/filtered out.

Coast Guard–wise, we’re so small over there that I think we want to be unnoticed, but it’s kind of hard to hide Americans in a totally different place. We weren’t allowed to be in uniform, except for on the boat or on base. We couldn’t have anything that said “United States,” any teams for the United States, like the Texas Longhorns—couldn’t wear any of that while I was there. Just had to come in regular clothes. Low profile.

Corporal Maria Holman Weeg, U.S. Marine Corps

I was begging to go, actually. I was like, “Yeah, I’m gonna go get some,” you know? Me and a bunch of friends—that’s all we’d do is pretty much train for deployment, and I was working a drug dog for the first year, when I was on the island. And drug dogs on the island, they don’t deploy. You stay stuck on Okinawa. So, I was really pretty bummed out about that. I was doing a lot of custom missions. I got to see a lot of things, but I definitely just wanted to get out and really understand what the whole Marine Corps was about. So, when I got my explosives dog, I was super excited. I was like, “Yes, I’m going to Iraq.” I guess there was a little bit of nervousness, but I was definitely overwhelmed with excitement.

My first impression: it was nighttime, and the stars were immaculate. As soon as you got out of the aircraft, the land is completely flat in Iraq, and so you can see all 180 degrees, and the whole entire sky was filled with stars—I mean, the brightest I’ve ever seen. I grew up in the country, so I thought the stars were pretty there, but then when I got there, I was like, “And this is a hostile place? This is wonderful. This is beautiful.” We were on the flight line, so

Airman Victoria Hager, U.S. Coast Guard

it was all concrete, and you didn’t see any sand, and it was dark, and I was like, “I thought this was supposed to be the desert.” But I waited till the morning and then I figured out, “Yeah. I’m in Iraq.”

Captain Beth Rohler, U.S. Army

Deployment for me was an amazing experience. It was a privilege to be over there, to be doing what I was doing, especially supporting the war fighters. Taking care of them, boosting their morale. It was peaceful.

I mean you don’t want to think of Iraq as a peaceful place. We get so wrapped up in a lot of the little things here, but you’re there to do your mission, and that’s what you do. You do your mission; you make sure it’s taken care of. There were quite a few scares. Being on the road, your heart just pounds the whole time you’re out there. But it’s an adrenaline pounding, and I looked forward to convoy days to get out and actually stretch my legs, get off the FOB, and just get in there. So I really enjoyed my deployment experience.

I honestly believe—and I’ve talked to a lot of people who feel this way—if it weren’t for families back home and things like that, shoot, I would be deployed my entire army career if I could, because it really gives you a sense of meaning. It’s like any job: you get in a rut, and every day I do the same thing, and I go to meeting after meeting after meeting. What am I really here for, what’s my real mission? Over there, you know. You’re there to do one thing, and that’s what you do. And it’s really great, having a purpose.

For a year in Iraq, you know what you’re gonna wear. There’s no choices in wardrobe: you either wear this, or you wear a set of physical training uniforms. And no civilian clothes. You go to the D-Fac to eat, and you might have three main dishes to choose from. You eat what’s there; it’s good food. So when I came home, making decisions was hard.

Specialist Elizabeth Sartain, U.S. Army, Retired

When I was able to pick anything I wanted within the medical field because of my high score, I asked the recruiter, “What’s mortuary affairs?” He said, “You’re only the second person in ten years to ever pick that MOS.” I was pretty curious about it, so I decided without any further education that that’s what I was going to do.

I just think about our poor fallen soldiers. My heart goes out to those families. The devastation we saw was so incredible. When we went to AIT, there was only small-arms fire. There were no IEDs, so we weren’t really prepared to see what our fallen comrades looked like when they came to us.

When we work on the remains, we go through their personal property. We see letters from their family, pictures, a baby sonogram, and we have to double check to make sure if they have a wedding ring on. I just felt guilty for doing that.

We had some high-profile cases. Back when I was deployed, there were seven soldiers who had disappeared, and it was all on the news. We only received three out of the seven. You could see how they were tortured alive. And then to see their families on the TV not wanting to believe that this was their child. They still wanted to believe that their child is out there, you know, alive. So that was very, very hard.

Airman Victoria Hager, U.S. Coast Guard

I’d never been on that big of a boat ever—to live on. I was supposed to live with twenty-one people on this 110-foot boat. We went through the kitchen area, which is called the galley, and it was so little. And all of us were supposed to eat in there. I had no idea how that was supposed to work. The most traumatizing part was we went into my bedroom, and she showed me my rack. It looked like a shelf—a cabinet. I was like, “I’m supposed to sleep up there?” It took a while for me to get accustomed to it all.

We guarded the two oil platforms over there that were Iraqi. We’d get tasked with the boardings—we’d go on tankers, or we’d go on dhows. We’d go alongside and take them food, water, everything. We’d go on there just to show them that we’re friendly: we’re not there to hurt them, we’re not there to hinder what they’re doing.

My boat was a go-to boat, so we were always out working. We had very short in-ports. You have watch twenty-four hours any time, but they put you on probably two watches a day, sometimes one if you had a good rotation. You would have your meals when you could get ’em, eat whatever you can really fast. Say I’d have watch from midwa...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- When Janey Comes Marching Home

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Why I Joined

- Earlier Wars

- Deployment

- Relationships with Iraqis and Afghans

- Contractors

- Spirituality

- The Mission

- Motherhood

- Coming Home

- Changing Relationships

- Women in the Military

- Terminology

- Notes

- Suggestions for Further Reading

- About the Photographs

- Acknowledgments