![]()

[ 1 ]

THE HAIRLESS INDIAN

Savagery and Civility before the Civil War

AMERICANS TEND TO remember Thomas Jefferson for many things, but his thoughts about hair removal are not generally among them. Nevertheless, Jefferson expressed a studied opinion on the matter in his only book, Notes on the State of Virginia (1785). He turned to hair in a long passage enumerating the distinctions he detected between “the Indians” and “whites”:

It has been said that the Indians have less hair than the whites, except on the head. But this is a fact of which fair proof can scarcely be had. With them it is disgraceful to be hairy on the body. They say it likens them to hogs. They therefore pluck the hair as fast as it appears. But the traders who marry their women, and prevail on them to discontinue this practice, say, that nature is the same with them as with the whites.1

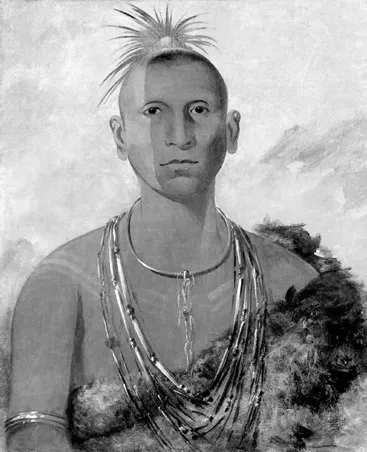

Were Indian bodies naturally hairy like those of settlers from Europe, only appearing otherwise due to some strange habit? Or were Indian bodies irrevocably different from those of whites? Jefferson was far from the only eighteenth-century observer preoccupied with this enigma, or with the absence of “fair proof” of an answer.2 From the 1770s through the 1850s, the enigma of Native depilatory practices preoccupied European and Euro-American missionaries, traders, soldiers, and naturalists. Scores of commentators pondered whether the continent’s indigenous peoples had less hair by “nature” or whether they methodically shaved, plucked, and singed themselves bare (figure 1.1).

Rarely distinguishing between the diverse indigenous peoples of the Americas in this regard (instead lumping geographically and linguistically dissimilar groups together as “Indians”), white writers both famous and now forgotten sought to explain the smooth faces and limbs that they viewed as typical of the original “Americans.”3 Cornelis de Pauw, for instance, saw the complete absence of beard as one of the distinctive physiological characteristics of Indian bodies.4 In contrast, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark concluded that Chopunnish men “extract their beards” like “other savage nations of America,” while Chopunnish women further “uniformly extract the hair below [the face].”5 In 1814, the renowned German explorer Alexander von Humboldt conceded that even the most “celebrated naturalists” had failed to resolve whether the Americans “have naturally no beard and no hair on the rest of their bodies, or whether they pluck them carefully out.”6

These were hardly idle musings. For European and North American observers, such questions of natural order entailed consequential questions of political order: whether Indians might be converted to European ways of life, or whether some fundamental, unalterable difference rendered assimilation impossible. The French naturalist Comte de Buffon’s famous Histoire naturelle held to the latter position, asserting that “the peculiar environment of the New World” had “stunted” the peoples he called aborigines, making it unlikely that they could ever be “admitted to membership in the new republic.”7 As the Pennsylvania-born naturalist and traveler William Bartram posed the problem in 1791, at issue in Indian hairlessness was whether Indians might be persuaded to “adopt the European modes of civil society,” or whether they were inherently “incapable of civilization” on whites’ terms.8 Body hair encapsulated these debates. More than one writer claimed rights of dominance over Indian lands because, as Montesquieu explained, Native men possessed “scanty beards.”9 In this context, Jefferson himself well understood the stakes of his discussion: Native peoples’ inherent rights to self-determination.10

Figure 1.1. George Catlin’s 1832 portrait of Náh-se-ús-kuk, eldest son of Black Hawk. Catlin, like other white travelers and naturalists of the period, was preoccupied with the smooth skin of Native peoples. (Reproduced with permission of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.)

With Andrew Jackson’s election to the U.S. presidency in 1828, the question of Indian governance moved to the forefront of federal policy. Jackson’s proposal to forcibly “remove” remaining southeastern Indians west of the Mississippi provoked fierce opposition. Nonetheless, thousands of U.S. troops were sent to Georgia, resulting in the immediate beatings, rapes, and murders of countless Cherokees, and the eventual deaths of thousands more on the Trail of Tears. By 1837, most members of the five southeastern nations had been relocated through what historian Daniel Heath Justice has characterized as a “ruthless and brutal terrorism campaign.”11 With the expansionist policies ushered in with the election of James Polk in 1844, Native peoples living in California, the Southwest, and the Northwest were subjected to similar federal jurisdiction.12

Whether or not white writers explicitly addressed these political developments, their perspectives on Indian body hair—the crux of debates over the nature of Indian racial character—necessarily engaged larger, ongoing disputes over the sovereignty of Native governments, the sanctity of treaties, and the appropriate use of federal force. The historical import of those disputes cannot be overstated. “If slavery is the monumental tragedy of African American experience,” Tiya Miles writes, “then removal plays the same role in American Indian experience.”13 White assertions of Indian beardlessness contributed to a body of racial thought that helped to buttress those policies and practices of physical removal.14 As the Pequot intellectual William Apess summarized in 1831, “the unfortunate aborigines of this country” have been “doubly wronged by the white man”: “first, driven from their native soil by the sword of the invader, and then darkly slandered by the pen of the historian. The former has treated him like beasts of the fores[t]; the latter has written volumes to justify him in his outrages.”15

Taken together, the volumes written about Indian body hair in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries—none, so far as I have been able to locate, written by Native authors themselves—reveal the asymmetrical production of consequential standards and categories of difference. Like other “racial” differences, assessments of body hair at once reflected and supported emerging military and political regimes. But quite unlike skin color, skull size, and the myriad other anatomical characteristics used by naturalists and ethnologists to sort and rank people, body hair was both readily removable and remarkably idiosyncratic in its rate of return. Hair’s unusual visibility and malleability allowed numerous, conflicting interpretations. In the midst of violent contestation over Indian policy in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, those conflicting interpretations loomed large in American racial taxonomies.

It is worth emphasizing that these taxonomies are the product of European and Euro-American points of view. The few extant written accounts of Native attitudes toward hair, such as Jefferson’s (“They say it likens them to hogs”), are filtered through imperial lenses. Moreover, although the writers described here often mentioned both female and male hair removal, most of the debate over Indian depilation focused on male bodies, and specifically male beards. The absence of prolonged discussion of other parts of the body—such as the female pubic region—suggests an intriguing feature of early American natural history: with regard to body hair, at least, Indian men were the object of naturalists’ most meticulous deliberations. Given the partial nature of these accounts, they might best be approached not as conclusive descriptions of so-called Indian bodies in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, but as a window into the perceptions, anxieties, and curiosities of the dominant culture. Through that window we may observe a set of questions about the nature of difference that persist to our time: What explains variation in human bodies? How do particular environments influence the expression of heritable traits? What, in the end, is “race”?

THE USE OF hair as an index of political capacities has roots in Enlightenment natural philosophy. When Linnaeus introduced his famous system of taxonomical nomenclature in 1735, he began by asserting four distinct “varieties” of Homo sapiens. Hair color, type, and amount (“black, straight, thick,” “yellow, brown, flowing”) were the leading indicators of each variety, followed in turn by each group’s alleged political characteristics, such as “regulated by customs” or “governed by caprice.”16 Buffon similarly joined body hair to capacities for reason and civility when claiming that the absence of body hair on “the American savage” reflected a deeper lack of will and motivation. The Indians’ efforts represented not the deliberate exercise of reason but rather “necessary action” produced by animal impulse. “Destroy his appetite for victuals and drink,” he declared, “and you will at once annihilate the active principle of all his movements.”17 The political implications of this physiological inertia were clear to Buffon: “[N]o union, no republic, no social state, can take place among the morality of their manners.”18 Hairlessness was thus thought to indicate whether indigenous peoples might be treated as equal subjects, or whether some inherent “feebleness” precluded incorporation into “civilized” modes of life.19

These hierarchical distinctions were themselves steeped in humoral theories dating to the classical age. Humoral theory proposed that bodies were not bounded by the envelope of the skin but were instead profoundly permeable to diet, climate, sleep, lunar movements, and other external influences. Maintaining appropriate constitutional balance among the four humors—black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood—necessitated careful exchange between inside and outside, hot and cold, wet and dry. One’s resulting “complexion,” including body hair, was thought to reveal the balance of humors within, a balance as much moral as physiological.20 This humoral vision was racialized as well as gendered: for European women, a pale, porcelain complexion was particularly prized; while for men, lush beard growth was thought to imply a healthy constitution. Although fashions in white men’s whiskers varied across time, region, religion, occupation, and military status (Jefferson himself was generally clean-shaven, as were most U.S. presidents before Lincoln), most eighteenth-century naturalists echoed Galenic medical theory in equating thick beards with philosophical wisdom.21

Hence the moral and physiological question, Was the Indian’s seemingly smooth skin similarly subject to external influence? If so, which influences, exactly? Given the weighty political implications of their conclusions, European and Euro-American writers energetically debated the extent to which Indian complexion might be affected by food, weather, and mode of life. In a 1777 book used as a standard reference on Indians in both Europe and the United States until well into the nineteenth century, Scottish historian William Robertson concluded that the answer was no: the hairless skin of the Americans instead provided evidence of “natural debility.”22 “They have no beard,” he wrote in his History of the Discovery and Settlement of North America, “and every part of their body is perfectly smooth,” a “feebleness of constitution” mirrored in their aversion to “labour” and their incapacity for “toil.”23 Robertson insisted that the “defect of vigour” indicated by the Indian’s “beardless countenance” stemmed not from rough diet or harsh environment but from an inherent “vice in his frame.”24 Although “rude tribes in other parts of the earth” subsist on equally simple fare, he maintained, Indians alone remained “destitute of [this] sign of manhood.”25

Robertson was challenged on exactly that point by Samuel Stanhope Smith, later president of Princeton University. In the influential Essay on the Causes of the Variety of Complexion and Figure in the Human Species, Smith argued that apparent differences between white and Indian bodies were overblown. “The celebrated Dr. Robertson,” Smith chided in 1787, joined “hasty, ignorant observers” in claiming that “the natives of America have no hair on the face, or the body,” thus binding him “to account for a fact which does not exist.” Although “careless travelers” saw a “deficiency” of hair and presumed a “natural debility of constitution,” Indians were no different “from the rest of the human race” in this regard. As Smith concluded, the “hair of our native Indians, where it is not carefully extirpated by art, is both thick and long.”26 In Smith’s perspective, the “common European error” that “the natives of America are destitute of hair on the chin, and body” was vile not simply because it revealed a striking observational ineptness but more importantly because it ran counter to Genesis. Smith stressed the influence of diet, grooming, and other habits on perceived differences in hair growth as a way to affirm scriptural teachings on the unity of creation.27

As Smith’s essay on the causes of human variety suggests, lurking in descriptions of hair removal was a pressing concern: whether purposeful activity might effect lasting changes to physical form. From where did apparent differences between races, sexes, or species arise, if not from separate creations? The great German natural philosopher Johann Blumenbach, for instance, proposed that the “sc...