- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

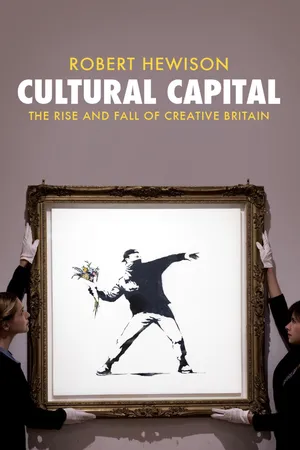

Britain began the twenty-first century convinced of its creativity. Throughout the New Labour era, the visual and performing arts, museums and galleries, were ceaselessly promoted as a stimulus to national economic revival, a post-industrial revolution where spending on culture would solve everything, from national decline to crime. Tony Blair heralded it a "golden age." Yet despite huge investment, the audience for the arts remained a privileged minority. So what went wrong?

In Cultural Capital, leading historian Robert Hewison gives an in-depth account of how creative Britain lost its way. From Cool Britannia and the Millennium Dome to the Olympics and beyond, he shows how culture became a commodity, and how target-obsessed managerialism stifled creativity. In response to the failures of New Labour and the austerity measures of the Coalition government, Hewison argues for a new relationship between politics and the arts.

In Cultural Capital, leading historian Robert Hewison gives an in-depth account of how creative Britain lost its way. From Cool Britannia and the Millennium Dome to the Olympics and beyond, he shows how culture became a commodity, and how target-obsessed managerialism stifled creativity. In response to the failures of New Labour and the austerity measures of the Coalition government, Hewison argues for a new relationship between politics and the arts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cultural Capital by Robert Hewison in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Contemporary Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

Under New Public Management

It is not part of our culture to think in terms of a cultural policy.

Senior official, Department of National Heritage, 1996

The ‘golden age’ of Creative Britain was presided over by a prime minister who showed little interest in the arts. It is the blunt opinion of the conservative columnist (and cultural politician) Simon Jenkins that Blair ‘had no grasp of history, culture or ideas’.1 At Oxford, Blair had played in a rock band and been a successful actor. He sometimes went to the theatre, but when he became prime minister he displayed overtly demotic tastes calculated by his press secretary Alastair Campbell to appeal to the tabloid newspapers, alarming the increasingly grumpy grandees who sat on the Boards of Britain’s cultural institutions.

In 1998 John Tusa was in a unique position to voice the concerns of the arts establishment. A distinguished broadcaster and former head of the BBC World Service, he had become managing director of the Barbican Arts Centre. The Barbican was fully funded by the wealthy Corporation of the City of London, so Tusa was beholden to neither the government nor its agency, the Arts Council. In March 1998 – at a time when New Labour was maintaining the previous Conservative government’s constraints on public funding for the arts – he confessed in an article for The Times, ‘I’m worried about Tony’:

The arts do not matter to him personally because they are a marginal and thinly-rooted side of his own experiences. He is a true child of the sixties, the rock and pop world is the one he likes instinctively; he is simply not at ease in the arts world. His evident lack of esteem for it – as evidenced by the way his government treats it – springs from this essential personal discomfort.2

Tusa made a larger and more important point about the direction Blair’s government was taking, something that concerned far more than the cultural establishment: ‘In backing “the arts that pay”, and overlooking and undervaluing “the arts that cost”, Blair shows himself to be the true son of Margaret Thatcher.’3 Though the creators of ‘New’ Labour were reluctant to admit it, neoliberal ideas had become the orthodoxy. The continuities between Blairism and Thatcherism were such that the political scientist Colin Hay could write, apparently without irony, that Blair’s election was a return to consensus politics in Britain – the consensus being that there was ‘simply no alternative to neoliberalism in a era of heightened capital mobility and financial liberalisation – in short, in an era of globalisation’.4

In order to make his party electable, Blair had abandoned the collectivist values of old Labour and accepted the primacy of individualism, private enterprise and the market that had been established under Thatcher. In his 1996 collection of speeches, New Britain: My Vision of a Young Country, he argued: ‘There will, inevitably, be overlap between Left and Right in the politics of the twenty-first century. The era of the grand ideologies – all-encompassing, all-pervasive, total in their solutions, and often dangerous – is over. In particular, the battle between market and public sector is over.’5 To borrow Francis Fukuyama’s phrase, it was the end of history, and the market had won. This did not mean the end of the public sector: like Thatcher, Blair combined neoliberalism with a neoconservative moralism that called for a strong, if smaller, state. The public sector would have to conform to the principles of the market, accepting privatization and partnership with private finance. The Bank of England would manage the economy in the market’s interests. The market demanded labour flexibility, so although the government signed up to the Social Chapter of the Maastricht Treaty, British trades unions regained few of the privileges they had lost under Thatcher. The government committed itself to tackling child poverty and established a minimum wage, but the welfare state would have to face ‘modernization’. Initially New Labour kept to the tight spending plans of the defeated Conservatives – bad news for the cultural sector, which depended on public funding to sustain the activities and institutions that fed the commercially profitable leisure industry.

Although his themes were developed in opposition, it was not until Blair was in power that he found the right label for the new politics that he was practising. The brand he wanted to promote sounded ominously like a New Age management theory: the ‘Third Way’. This sought to go, as argued in the title of a book by Blair’s policy guru, the director of the London School of Economics, Anthony Giddens, Beyond Left and Right. Blair made this clear in a pamphlet for the Fabian Society in 1998: The Third Way: New Politics for a New Century: ‘It is a third way because it moves decisively beyond an Old Left preoccupied by state control, high taxation and producer interests; and a New Right treating public investment, and often the very notion of “society” and collective endeavour, as evils to be undone.’6

Blair explicitly accepted Mrs Thatcher’s ‘necessary acts of modernization’,7 and declared that the era when big government meant better government was over. Leverage, not size, was what mattered – leverage applied through the market: ‘With the right policies, market mechanisms are critical to meeting social objectives, entrepreneurial zeal can promote social justice.’8 Through an approach that he called ‘permanent revisionism’, Britain would achieve a ‘dynamic knowledge-based economy founded on individual empowerment and opportunity, where governments enable, not command, and the power of the market is harnessed to serve the public interest’.9

The ideal of the ‘enabling state’ presiding over a strong self-governing society implied the decentralization and increased local autonomy that he had advocated in New Britain. As the political scientist Alan Finlayson put it, government became like a head office, franchising out its operations to agencies that were allowed to operate independently, but always subject to rules from above.10 Blair’s pamphlet warned: ‘In all areas, monitoring and inspection are playing a key role, as an incentive to higher standards and as a means of determining appropriate levels of intervention.’11

Like David Cameron’s Big Society, Blair’s Third Way did not catch on with the general public, and was treated with considerable scepticism by the press. The critical discourse analyst Norman Fairclough dismissed the government’s use of linguistic sleight of hand as ‘Thatcherism with a few frills’.12 The political scientist David Marquand identified the continuities early on:

Like the Thatcher governments before it, New Labour espouses a version of the entrepreneurial ideal of the early nineteenth century. It disdains traditional elites and glorifies self-made meritocrats, but it sees no reason why successful meritocrats should not enjoy the full fruits of their success: it is for widening opportunity, not for redistributing reward. By the same token, it has no wish to undo the relentless hollowing out of the public domain or to halt the increasing casualisation of labour – white collar as well as blue collar – that marked the Thatcher years.13

This did not mean that there was no such thing as society; New Labour’s version of neoliberalism was the ‘stakeholder society’, where the individual earned the right to reward by active participation and investment in the values of ‘the community’, made possible by the enabling state. According to Blair, this was not socialism but – breaking apart the word that attached his party most firmly to its roots – ‘social-ism’,14 which would free Labour from its history. As the political scientist Mark Bevir puts it, ‘New Labour’s Third Way is one of competitive individualism within a moral framework such that everyone has the chance to compete. It feeds hefty doses of individualism, competition, and materialism into the traditional social democratic ideal of community.’15

But in spite of the apparent freedom for individual and collective enterprise offered by the enabling state, and Blair’s assertion of the need for devolution and the revival of local government, New Labour was not prepared to release the levers of control, and busily developed new ones. When it came to the relationship between the centre and the periphery, between London and the regions, between national and local government, the centre stayed in charge.

Yet, although London exerted a powerful centripetal force, separate national and regional cultural identities remained strong. Scotland retained its own legal and educational systems; Wales held on to its language; Northern Ireland defined itself by its separation from the mainland and its sectarian divisions. The great nineteenth-century commercial and industrial centres – Belfast, Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle, Sheffield, together with many other towns and cities – had created their own museums and art galleries, orchestras and theatres, that were just as worthy of support as the ‘national’ cultural facilities in London, and could produce work of as high a standard.

The cultural infrastructure depended on elected local authorities, which varied in size and responsibility from large urban metropolitan authorities to small district councils in rural areas. These owned and supported the majority of the buildings – other than most cinemas and a few theatres – where cultural activity took place, but, with the exception of a legal obligation to provide a public library service, local authorities had complete discretion over cultural spending, and no central government support.16

As a result, the financial contribution by local authorities to culture was uneven, and it is emblematic of the fragmented nature of the system that it is very difficult to arrive at an accurate total. In 2009/10, the combined sum for spending by English local authorities on arts, leisure (including sport), heritage, museums and libraries peaked at £3.5 billion. Defined more narrowly, when New Labour came to power the aggregate of local authority revenue spending on activities corresponding to those funded by the Arts Council was put at £190 million a year.17 This was marginally more than the Arts Council’s contribution, but represented less than 1 per cent of total local authority expenditure.

The nominal parity of local authority and Arts Council funding streams to the same organizations led to an expectation by the Arts Council that it could use its grants to leverage matching local authority funding – but there was a crucial difference in motivations. Ever since its formation in 1945, the Arts Council had supported the arts for what it saw as aesthetic reasons – that is to say, what it believed to be the intrinsic value of the art forms themselves. Local authorities, however, were looking for directly beneficial social and economic outcomes – an instrumentalism that New Labour would adopt and extend.

New Labour’s attitude to the dispersal of power away from the centre was contradictory. It granted a form of self-government to Scotland and Wales, and returned it to Northern Ireland; it gave responsibility for London to a directly elected executive mayor. Yet local government was subjected to the same kind of centralizing Treasury control as Whitehall ministries. Local authorities were swamped by zones, pilots and initiatives, and demands for plans and strategies, and subjected to multiplying regimes of inspection. Local government had already lost much of its autonomy under Thatcher, and regardless of New Labour’s talk of reviving regionalism, central government was reluctant to surrender the powers it had gained. In spite of the government’s ‘New Localism’, its attempts to decentralize power were limited.

Because New Labour raised spending on public services, local authorities received substantial increases in their budgets, and so appeared to be less oppressed than during the Thatcher years. But only about 20 per cent of their spending was locally financed, making them increasingly dependent on central government. In 1999 the 353 local authorities in England were told to develop local cultural strategies, but there was no move to make their cultural spending statutory. Between 1981 and 1986, as leader of the Greater London Council, the municipal socialist Ken Livingstone had demonstrated the way in which a local authority could use the cultural resources at its disposal. When he returned as the first elected mayor of London in 2000, he found that the new Greater London Authority was responsible for policing, planning and transport, but had little of the cultural clout of the GLC before its abolition, and an arts budget of less than £250,000 a year.

Within England, New Labour established nine administrative regions, each with a Regional Development Agency (RDA) whose members were appointed by government, and ‘supported’ by appointed regional chambers made up of local authority members and other interested parties. The intention was to follow these with elected regional assemblies, but after a local referendum rejected proposals for an elected assembly for the north-east region in 2004, New Labour lost interest in regional government. Blair’s frustration that Ken Livingstone beat the official Labour candidate to become mayor of London as an independent added to the government’s disenchantment with regional democracy. The purpose of the RDAs was economic development: cultural projects, co-funded by the National Lottery, local authorities and the European Union, were given a leading role in urban regeneration schemes.

The overweening urge to centralize policy decisions in Whitehall was yet another manifestation of the theory of government known as the New Public Management, which had developed over the eighteen years of the Thatcher and Major administrations. The idea was to bring greater accountability to the management of public services by establishing measures of performance and contractual relationships between departments and agencies based on the principle of Value for Money, which would be judged by the three ‘Es’ of Efficiency, Effectiveness and Economy. In 1991 the editor of Public Administration, R. A. W. Rhodes, gave a capsule definition of the New Public Management: ‘The disaggregation of public bureaucracies into agencies which deal with each other on a user-pay basis, the use of quasi-markets and contracting out to foster competition; cost cutting; and a style of management which emphasises, among other things, output targets, limited term contracts, monetary incentives and freedom to manage.’18

In neoliberal fashion, government departments and the ‘Next Steps’ agencies that increasingly took on their responsibilities were now expected to behave less like disinterested, hierarchically structured bureaucracies, and more like wealth-creating corporations competing in a market for resources. Yet, although the intention was to achieve the freedom of manoeuvre and efficiency attributed to the market, in practice those responsible for delivering public policy became more constrained. Strategic plans had to be prepared, objectives identified, benchmarks set, targets established, measures agreed and impacts assessed.

The master of the system was the Treasury. It decided the spending allocations of the other ministries, and favoured those that achieved their targets. In t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Epigraph

- Introduction: ‘A Golden Age’

- 1. Under New Public Management

- 2. Cool Britannia

- 3. ‘The Many Not Just the Few’

- 4. The Amoeba – and Its Offspring

- 5. ‘To Hell with Targets’

- 6. The Age of Lead

- 7. Olympic Rings

- 8. Just the Few, Not the Many

- Conclusion: What Next?

- Notes

- Bibliography