![]()

CHAPTER 1

Breaking It Down: Who Does What

Theater is collaborative. We never do it alone. There’s no such thing as a one-man show. Being backstage means being surrounded by people—people who assume a wide variety of titles and responsibilities. As a show person, you do not need to know how to do all their jobs. You do not have time to do all their jobs. You need to know who to talk to when the carpet is coming up behind the podium, or the work light backstage is burned out, or the Frosty the Snowman costume is ripping open. Scenic designers, prop coordinators, stage managers, tech directors, first hands, flymen—they surround you at every turn, and, if they are any good, they are there to help you. So who are all these people? And who can help you staple down that carpet?

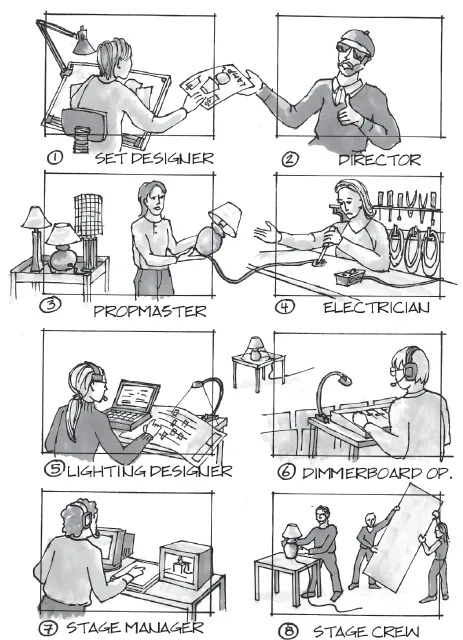

Not an easy question. There are constant overlaps between areas of responsibility, and many things must be worked out case-by-case. Sometimes a simple task requires input from several departments. Consider this example: The script calls for a lamp to be sitting on a table. The scenic designer talks to the director and decides what the lamp should look like. Then the designer shows the design to the propmaster, who either buys the item, pulls it from stock, or builds it. The finished lamp is brought to the stage, where the electrician wires it up. The lighting designer decides how big of a bulb to put in it and when it should be on (with more input from the director). The lighting designer then communicates that information to the dimmerboard operator who, under the direction of the stage manager, operates the light during the show. If the light has to move during a scene change, that task is the responsibility of the stage crew chief. One object—eight people. Hard to believe we get anything done at all.

Talking to the wrong person, however, can gum up the works pretty good. Consider poor, hapless director Steve, who tells the dimmerboard operator to turn the lamp on later than he did last night, thereby circumventing normal procedure and causing the following headset conversation:

Stage Manager: Light Cue 49 go.

Dimmerboard Operator: No, not yet.

SM: What?

DBO: Not yet, he said he wants it later.

SM: Who?

DBO: Steve.

SM: What? When?

DBO: Before the show.

SM: No, I mean when does he want it? He didn’t tell me. Are you sure?

DBO: Are you saying I don’t know my job? Hey, I’m just doing what I’m told here.

SM: Well, I want to be sure. Where is he?

Assistant SM (from backstage): I think he’s in the bathroom.

SM: Well, um …

DBO: All I want is for somebody to tell me what to do.

Lighting Designer (suddenly coming onto the headset): Hey, what planet are you people on? Cue 49 is late and you’ve missed two more. Let’s go!

SM: Well, he said he wants it later.

LD: Who did?

SM: Steve.

LD: What? When?

SM: Before the show!

LD: No, I mean, when does he want it? And why the heck haven’t you called Cue 50?

SM: I should call it now?

Fig. 1. Who’s in charge of the lamp?

LD: YES!! Go now! GO, GO, GO!!

Follow Spot Operator: Is that Go for us?

SM: Yes, I mean NO! Who said that?

DBO: Well, I think we should Go.

SM: Fine, Go! Everybody Go!

Stage Crew Chief: OK, main curtain coming in!

Meanwhile, Steve, the well-meaning director, returns from his trip to the bathroom to find follow spots crisscrossing the auditorium, the main curtain bouncing up and down, and a gaggle of actors standing bewildered on the stage, trying to improvise themselves into the wings because the scene-ending blackout never happened.

If we are to work together, then, it must be with predetermined areas of responsibility and lines of communication. Most things fit pretty neatly into one of the following six categories: costumes, props, lighting, sound, stage management, and scenery.

Costumes

Any kind of clothing, or anything at all worn by a performer, including masks and jewelry, is considered a costume. Makeup and wigs are sometimes handled by separate departments, but they are usually treated as a subset of the costume shop. This area is designed by the costume designer and is managed by the costume shop manager, who is assisted by a first hand, as well as cutters, stitchers, and drapers. During the run of the show, costumes are handled by the dressers.

Props

Anything that is carried by an actor, or could be carried by an actor within the context of the play, is a prop. Pictures on the wall, for example, are props, because an actor, while portraying a character, could move them. A kitchen countertop, however, is scenery because the character he is playing would not rip up and move a real countertop, even though the actor himself might be able to do so. It is a tenuous definition. The distinction between props and scenery gets muddy at times, and clear assignments should always be made at the start of the building process. Props are designed by the prop designer (or the set designer if there is no prop designer), and managed by the propmaster (prop coordinator). Props are built by prop carpenters and craftspeople, and handled during the run by the props crew, a subset of the stage crew.

Lighting

Anything electrical that is not sound equipment is the responsibility of the lighting department. There are two exceptions to this: the “running” lights, which are the small (generally blue) lights that allow people to see in the darkened backstage areas, and the “ghost” light, the naked bulb on the tall stand that gets set out on the stage when the theater is empty. Both these lights are usually set up by stage managers. In a theater with union stage crews, the ghost light is the only light on the stage that does not have to be turned on by a union electrician. The arrival of the ghost light center stage means that the work call is over, and the union workers must clock out. Whether you are union or not, the ghost light keeps people from killing themselves in a dark theater. Lighting is designed by the lighting designer and managed by the master electrician, with the assistance of the electrics crew. The lights are operated during the run by the dimmerboard operator and, if spots are used, the follow spot operators.

The lighting cues (the instructions that tell the lighting operators what to do and when to do it) are handled by three different people. The lighting designer creates the content of a cue (what lights are on and how bright) as well as its time (how fast the lights change from one “look” to another). During the performance, however, it is the stage manager who gives the command to perform the cue and the dimmerboard operator who actually pushes the buttons. In technical terms, we say that the stage manager “calls” the cue and the operator “runs” it.

Sound

Microphones, sound effects, and the playback of recorded sound are all part of the sound department. Sound people also should handle headsets for backstage communication. The sound designer is in charge of this area. Sound is often a one-person operation, but if the sound designer doesn’t run the show, there will be a separate sound engineer. If you have a large live band on stage, there also might be a second engineer running a separate mixer, called a monitor mixer, that feeds the monitor speakers that the band uses to listen to themselves. When the sound system is first installed, there may be additional sound crew people in the theater.

Stage Management

The stage manager handles rehearsal schedules, runs the rehearsal itself, provides assistance to the director, and, during the run, is in charge backstage. The SM is also responsible for being a clearinghouse of information about the entire production process. When in doubt, ask the stage manager, particularly if the question has to do with schedule.

Almost all stage managers have at least one assistant, the ever-useful assistant stage manager (ASM). The ASM is the gofer position, the essential yet thankless job of getting done whatever needs to get done. It is impossible to predict when you will need an errand run, when you will need a prop handed to an actor, why you will need a curtain pulled back, a phone answered, or an animal fed, but one thing is for sure: it will be the job of the ASM. Besides being an everything-to-everybody position, it is also a primary training position, the entry-level job in the backstage world.

The company manager makes all travel, lodging, and food arrangements for the cast and crew.

Finally, many companies have a production stage manager (PSM) who oversees the entire production process. The PSM is responsible for coordinating the whole process. In the Broadway theater world, the PSM works for the producer and moves from show to show, releasing day-to-day control of each show to the stage manager when it opens. In regional or repertory theater, the PSM is in charge of the entire season, while each show has its own stage manager. In one-shot productions, the PSM is often the stage manager as well.

You should not forget the position of PSM just because your theater is nonprofessional. It is mighty useful to have someone overseeing the entire process, especially if she does not have to worry about the moment-to-moment rehearsal process, as the stage manager does. A good PSM makes everybody’s process smoother and more creative.

Scenery

Anything that I have not already mentioned is scenery. Not surprisingly, scenery is designed by the scenery designer and is managed by the technical director (TD). “Technical director” is a very loose job description, one of the loosest in the business, but usually he is in charge of deciding how the set will be built. Sometimes, he also oversees the properties and lighting crews, particularly in small theaters. His oversight, however, is always limited to practical matters, such as money, equipment, and staff. He is not a designer and should never be put into the position of making design decisions.

The TD is the voice of reason in the technical process, which, unfortunately, often makes him the bearer of bad news. The TD is the one who must tell you that the effect you want is too expensive, time-consuming, or unsafe. His opinion may bring you down occasionally, but it’s better to know that your idea won’t work ahead of time, instead of at first tech.

The scenery is built in the scene shop. This shop usually has a scene-shop manager or master carpenter (unless the technical director does it) who is in charge of carpenters and welders. In the paint shop, scenic artists do the painting and decorating under the supervision of the charge artist. During the run, the scenery is handled by the stage crew and their chief. Flying scenery is operated by the flyman.

Remember, if you have any doubt about whom to ask, go to the stage manager. The stage manager is always the best port in a storm.

You might be saying to yourself at this poin...