Galois' Theory of Algebraic Equations

Jean-Pierre Tignol

- 324 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

Galois' Theory of Algebraic Equations

Jean-Pierre Tignol

Über dieses Buch

The book gives a detailed account of the development of the theory of algebraic equations, from its origins in ancient times to its completion by Galois in the nineteenth century. The appropriate parts of works by Cardano, Lagrange, Vandermonde, Gauss, Abel, and Galois are reviewed and placed in their historical perspective, with the aim of conveying to the reader a sense of the way in which the theory of algebraic equations has evolved and has led to such basic mathematical notions as "group" and "field".

A brief discussion of the fundamental theorems of modern Galois theory and complete proofs of the quoted results are provided, and the material is organized in such a way that the more technical details can be skipped by readers who are interested primarily in a broad survey of the theory.

In this second edition, the exposition has been improved throughout and the chapter on Galois has been entirely rewritten to better reflect Galois' highly innovative contributions. The text now follows more closely Galois' memoir, resorting as sparsely as possible to anachronistic modern notions such as field extensions. The emerging picture is a surprisingly elementary approach to the solvability of equations by radicals, and yet is unexpectedly close to some of the most recent methods of Galois theory.

Request Inspection Copy

The book gives a detailed account of the development of the theory of algebraic equations, from its origins in ancient times to its completion by Galois in the nineteenth century. The appropriate parts of works by Cardano, Lagrange, Vandermonde, Gauss, Abel, and Galois are reviewed and placed in their historical perspective, with the aim of conveying to the reader a sense of the way in which the theory of algebraic equations has evolved and has led to such basic mathematical notions as "group" and "field".

A brief discussion of the fundamental theorems of modern Galois theory and complete proofs of the quoted results are provided, and the material is organized in such a way that the more technical details can be skipped by readers who are interested primarily in a broad survey of the theory.

In this second edition, the exposition has been improved throughout and the chapter on Galois has been entirely rewritten to better reflect Galois' highly innovative contributions. The text now follows more closely Galois' memoir, resorting as sparsely as possible to anachronistic modern notions such as field extensions. The emerging picture is a surprisingly elementary approach to the solvability of equations by radicals, and yet is unexpectedly close to some of the most recent methods of Galois theory.

Request Inspection Copy

Readership: Upper level undergraduates, graduate students and mathematicians in algebra.

Key Features:

- Describes the problems and methods at the origin of modern abstract algebra

- Provides an elementary thorough discussion of the insolvability of general equations of degree at least five and of ruler-and-compass constructions

- Original exposition relying on early sources to set classical Galois theory into its historical perspective

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Information

Chapter 1

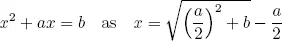

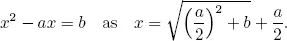

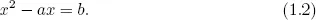

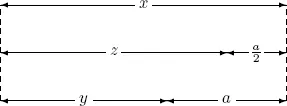

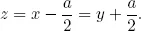

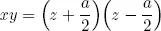

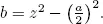

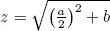

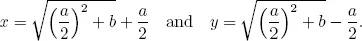

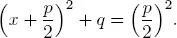

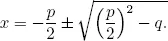

Quadratic Equations

1.1Babylonian algebra