Biological Sciences

Parasites in Food

"Parasites in food" refers to the presence of parasitic organisms in food products, which can pose health risks to consumers if ingested. These parasites can include protozoa, helminths, and other organisms that can cause infections and diseases. Proper food handling, cooking, and sanitation practices are essential for preventing the transmission of parasites through food consumption.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Parasites in Food"

- eBook - PDF

- Jack Chernin(Author)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

IN TR O D U C TIO N TO P A R A S I T O L O G Y ■ 1.1 PARASITES AND PARASITISM The w ord ‘parasite’ is derived from the G reek w ords para (m eaning beside) and sitos (m eaning food). Parasites can be described as living organisms that are associated w ith food for all or part of their life-cycle. The organism providing the food is generally called the host. A parasite has at least one host per life-cycle. If there is m ore than one host per life-cycle, the host in which sexual m aturity occurs is referred to as the definitive host and the other h o st/s are know n as interm ediate hosts. The study of parasites invariably involves firstly the biology of the parasite and secondly the biology of the host — the parasite’s environm ent. H ence the following com m ents can be made regarding parasitology: ■ Parasitology can be considered to be a specialised branch of ecology. ■ Parasitology is the study of organisms living w ithin a specialised environm ent. The problem s related to survival for parasites are alm ost the opposite of those faced by free-living animals. Parasites are surrounded by (they live w ithin or on) their food and do not need to spend energy to find food; w hereas free living animals are continuously searching for food. Free living animals have few er problem s than parasites in reproduc-tion and distribution. D uring the distributive phase of its life-cycle, the probability of a parasite making contact w ith a new host is relatively low . The evolution of successful m ethods of invasion and escape is essential for the survival of a parasite. Parasites have evolved mechanism s to ensure distribution and making contact w ith a new host. Similar adaptive strategies that follow a basic ‘parasitic’ plan/design have evolved w ithin different taxonom ic groups. - eBook - PDF

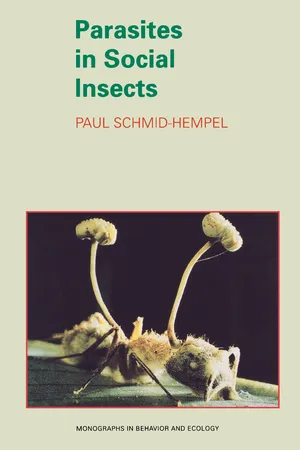

- Paul Schmid-Hempel(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

2 The Parasites and Their Biology In the ancient Greek world, a Parasitos was a person who received free meals from a rich patron in exchange for amusements and conversations (Brooks and McLennan 1993). Unfortunately, the term is not as easy to define in biology. Webster's International Dictionary defines it as an organism living in or on an-other living organism, obtaining from it part or all of its organic nutriment, commonly exhibiting some degree of adaptive structural modifications, and causing some real damage to its host. Obviously, this definition leaves out phe-nomena such as social parasitism and leaves open problems such as defining real damage. However, it seems almost impossible to give a universal definition, and, since social parasitism is not discussed in this book, we may just as well stick to such vague descriptions. In this chapter, an overview over the different parasite groups and their biol-ogy is given. The main emphasis is on those associated with social insects. A summary of the known parasites of social insects by taxonomic group is given in the lists in Appendixes 2.1 to 2.11. Not surprisingly, the number of parasite species (here called parasite richness) described from the different social in-sect taxa is related to how well they are studied in general, i.e., the sampling ef-fort (fig. 2.1 ). In the subsequent analyses, sampling effort will be controlled for by analyzing the residuals from the regression shown in figure 2.1 (the stan-dardized parasite richness) rather than the raw values themselves (Walther et al. 1995). Using the raw data, however, would not alter the major conclusions. The number of recorded parasite species per social insect host species is ap-proximately Poisson-distributed, with an average of2.63 ± 0.19 (S. E.; N = 488) recorded parasites ( 1.31 ± 0.14 pathogens, 1.32 ± 0.10 parasitoids) per species (fig. 2.2). - eBook - PDF

- Rathoure, Ashok Kumar(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Daya Publishing House(Publisher)

Parasitology is an applied field of biology dedicated to the study of the biology, ecology and relationships which parasites are involved in with other organisms known as the host. This ebook is exclusively for this university only. Cannot be resold/distributed. Depending on the specific bias, there are different fields of parasitology and some of these include medical parsitology, veterinary parasitology, structural parasitology, quantitative parasitology, parasite ecology, conservation of parasites, malariology, helminthology, parasite immunology etc. The term parasitism may be defined as a two species association in which one species i.e . parasite lives on or in a second species i.e . host for a significant period of its life and obtains nourishment from it. This is a commonly accepted working definition of parasitism and using it we can emphasize several important features of the host parasite relationship. The following are important features of parasitism: a. Parasitism always involves two species i.e . parasite and host. b. Many of these parasitic associations produce pathological changes in hoststhat may result in disease. c. Successful treatment and control of parasitic diseases requires not onlycomprehensive information about the parasite itself but also a goodunderstanding of the nature of parasites’ interactions with their hosts. d. The parasite is always the beneficiary and the host is always the provider inany host parasite relationship. This definition of parasitism is a general one but it tells us nothing about parasites themselves. It does not address which particular infectious organisms of domestic animals we might include in the realm of parasitology. The protozoa, arthropods and helminths are traditionally defined as parasites. However, there are members of the scientific community who designate all infectious agents of animals as parasites including viruses, bacteria and fungi. - eBook - PDF

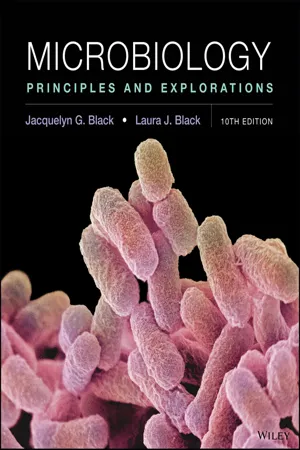

Microbiology

Principles and Explorations

- Jacquelyn G. Black, Laura J. Black(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Unless health scien- tists take a course in parasitology, their only opportunity to learn about helminths and arthropods is in conjunction with the study of microscopic infectious agents. PRINCIPLES OF PARASITOLOGY A parasite is an organism that lives at the expense of another organism, called the host. Parasites vary in the degree of damage they inflict on their hosts. Although some cause little harm, others cause moderate to severe damage. Parasites that cause disease are called pathogens. Parasitology is the study of parasites. Although few people realize it, among all living forms, there are probably more parasitic than nonparasitic organisms. Many of these parasites are microscopic throughout their life cycle or at some stage of it. Historically, in the development of the science of biology, parasitology came to refer to the study of protozoa, hel- minths, and arthropods that live at the expense of other organisms. We will use the term parasite to refer to these organisms. Strictly speaking, bacteria and viruses that live at the expense of their hosts also are parasites. The manner in which parasites affect their hosts dif- fers in some respects from that described in earlier chap- ters for bacteria and viruses. Special terms also are used to describe parasites and their effects. This introduction PRINCIPLES OF PARASITOLOGY 298 The Significance of Parasitism 298 • Parasites in Relation to Their Hosts 298 • Wolbachia 299 PROTISTS 300 Characteristics of Protists 300 • The Importance of Protists 300 • Classification of Protists 301 FUNGI 307 Characteristics of Fungi 307 • The Importance of Fungi 310 • Classification of Fungi 311 CHAPTER MAP HELMINTHS 315 Characteristics of Helminths 315 • Parasitic Helminths 316 ARTHROPODS 323 Characteristics of Arthropods 323 • Classification of Arthropods 323 to parasitology will make discussions of parasites here and in later chapters more meaningful. - eBook - ePub

Advanced Food Analysis Tools

Biosensors and Nanotechnology

- Rovina Kobun(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Biosensors are analytical instruments that transform biological reactions to electrical signals and are deemed promising because of their specific properties such as high sensitivity, ease of miniaturization, and rapid response. Biosensor and nanotechnology progress has recently increased as leading research in several forms of industrial or educational industries and provides opportunities to boost the potential generation of biosensor innovations that will improve the mechanical, electrochemical, optical, and magnetic features of biosensors with high-performance biosensor arrays. Nanotechnology-enabled goods are rapidly commonplace and one of the most promising technological developments that have contributed to significant advances in the modern diet and food sciences. Biosensors and nanotechnologies are increasingly emerging in current areas such as food, forestry, biomedical, medicinal, and pharmaceutical sciences, catalysis, and environmental regeneration. Since biosensor has high sensitivity and reliability, which is improved by the usage of nanomaterials that have rendered it possible to incorporate in the field of parasitology. Recent advances in biosensor development over the last few years have paved the way for potential researchers to improve these biosensory aspects further and optimize them for the identification of dangerous diseases triggered by parasites.Classification of parasites

Parasites look like roundworms, gross-looking tapeworms, fleas, or blood-borne diseases (malaria and schistosomiasis) ranging from several centimeters to many meters in length. Their size is very small compared to their food sources, which can protect them from predators, and they often consume other living things. Parasites are species that receive food from other living organisms; therefore, a “good” or well-adapted parasite will not destroy its host, as it relies on the host to provide food consistently over a long period of time. In the meantime, according to Doyle (2013) , those parasites live only in one animal species. Nevertheless, other parasites, especially worms, invest their sexually reproductive lives in a primary or definite host and emerge as larvae in an intermediate host of different organisms during another part of their lives.The protozoan parasite is a completely different class of eukaryotic organisms that can cause disease in living organisms. Robertson (2018) discovered that the majority of parasitic infections are asymptomatic, induce acute short-lived, as well as remain in the body causing chronic effects. This situation can be considered confined to tropical countries, primarily in areas with minimal sanitary facilities where the communities are typically eating raw and undercooked food. Generally, the transmission occurs through various sampling techniques, preparation routines, detection targets used, as well as through a variety of routes and vehicles, including soil, water, food, and human-animal contact (Ortega & Sterling, 2018 ; Rozycki et al., 2020 - Carla Gheler-Costa, Maria Carolina Lyra-Jorge, Luciano Martins Verdade, Carla Gheler-Costa, Maria Carolina Lyra-Jorge, Luciano Martins Verdade(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter Open Poland(Publisher)

Parasites, especially those that have complex life cycles involving more than one obligate host, are indicators of stable trophic structure in ecosystems. This is because all the biotic components necessary for completion of the life cycle must co-occur regularly in order to maintain any given parasite species. Knowing the complement of parasite species inhabiting any given host thus provides a means of rapid assessment of the breadth and form of trophic interactions of host species. Parasites are key to understanding the context of global change. Recently there has also been an increasing interest in the relationship between parasitism and pollution in the aquatic environment. Parasites may offer advantages over currently-used bioindicators including a more widespread distribution and a higher accumulation potential. Introduced parasites can have unpredictable and deleterious impacts on native species of hosts. It is therefore important to be able to quickly distinguish native from introduced parasite species. 10.1 Introduction Parasites by definition have a dependence on their host for their survival and growth. Behind this simple conception lies a complexity that reflects the degree of dependence, of virulence, or both, and how these vary in time and space. The notion of dependence © 2016 Rodney Kozlowiski de Azevedo, Vanessa Doro Abdallah This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. 164 Fish Parasites and their Use as Environmental Research Indicators is relative, not absolute. A particular parasite may lie somewhere along the scale of 0% metabolic dependence (or being absolutely free-living) to 100% metabolically dependent (or ‘totally’ parasitic). An ecologic rule specifies that an obligatory parasite should not kill (cause the ultimate harm to) its host to benefit from the adapted long-term symbiosis.- eBook - ePub

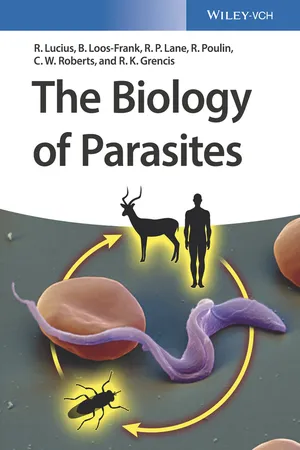

- Richard Lucius, Brigitte Loos-Frank, Richard P. Lane, Robert Poulin, Craig Roberts, Richard K. Grencis, Ron Shankland, Renate FitzRoy, Ron Shankland, Renate FitzRoy(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Wiley-VCH(Publisher)

Chapter 1 General Aspects of Parasite BiologyRichard Lucius and Robert Poulin- 1.1 Introduction to Parasitology and Its Terminology

- 1.1.1 Parasites

- 1.1.2 Types of Interactions Between Different Species

- 1.1.2.1 Mutualistic Relationships

- 1.1.2.2 Antagonistic Relationships

- 1.1.3 Different Forms of Parasitism

- 1.1.4 Parasites and Hosts

- 1.1.5 Modes of Transmission

- Further Reading

- 1.2 What Is Unique About Parasites?

- 1.2.1 A Very Peculiar Habitat: The Host

- 1.2.2 Specific Morphological and Physiological Adaptations

- 1.2.3 Flexible Strategies of Reproduction

- Further Reading

- 1.3 The Impact of Parasites on Host Individuals and Host Populations

- Further Reading

- 1.4 Parasite–Host Coevolution

- 1.4.1 Main Features of Coevolution

- 1.4.2 Role of Alleles in Coevolution

- 1.4.3 Rareness Is an Advantage

- 1.4.4 Malaria as an Example of Coevolution

- Further Reading

- 1.5 Influence of Parasites on Mate Choice

- Further Reading

- 1.6 Immunobiology of Parasites

- 1.6.1 Defense Mechanisms of Hosts

- 1.6.1.1 Innate Immune Responses (Innate Immunity)

- 1.6.1.2 Acquired Immune Responses (Adaptive Immunity)

- 1.6.1.3 Scenarios of Defense Reactions Against Parasites

- 1.6.1.4 Immunopathology

- 1.6.2 Immune Evasion

- 1.6.3 Parasites as Opportunistic Pathogens

- 1.6.4 Hygiene Hypothesis: Do Parasites Have a Good Side?

- 1.6.1 Defense Mechanisms of Hosts

- Further Reading

- 1.7 How Parasites Alter Their Hosts

- 1.7.1 Alterations of Host Cells

- 1.7.2 Intrusion into the Hormonal System of the Host

- 1.7.3 Changing the Behavior of Hosts

- 1.7.3.1 Increase in the Transmission of Parasites by Bloodsucking Vectors

- 1.7.3.2 Increase in Transmission Through the Food Chain

- 1.7.3.3 Introduction into the Food Chain

- 1.7.3.4 Changes in Habitat Preference

- Further Reading

1.1 Introduction to Parasitology and Its Terminology

1.1.1 Parasites

Parasites are organisms which live in or on another organism, drawing sustenance from the host and causing it harm. These include animals, plants, fungi, bacteria, and viruses, which live as host-dependent guests. Parasitism is one of the most successful and widespread ways of life. Some authors estimate that more than 50% of all eukaryotic organisms are parasitic, or have at least one parasitic phase during their life cycle. There is no complete biodiversity inventory to verify this assumption; it does stand to reason, however, given the fact that parasites live in or on almost every multicellular animal, and many host species are infected with several parasite species specifically adapted to them. Some of the most important human parasites are listed in Table 1.1 - Hanem Khater, M. Govindarajan, Giovanni Benelli, Hanem Khater, M. Govindarajan, Giovanni Benelli(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- IntechOpen(Publisher)

This is termed biological control or simply biocontrol. Biocontrol is therefore defined as “any activity of one species that reduces the adverse effect of another” [ 1 ]. Biocontrol can also be defined as “the study and uses of parasites, predators and pathogens for the regulation of host (pest) densities” [2 ]. Biological control differs from natural control in that the latter does not involve human manipulation. The organism that suppresses the pest population is generally referred to as a biological control agent (BCA). A parasite is an organism that lives and feeds in or on a host [ 3]. Parasites that invade and live within the host are referred to as endoparasites; meanwhile, those that live on the surface without invading the host are referred to as ectoparasites. Endoparasites include helminths and protozoa, and ectoparasites are fleas, ticks, mites, insects and so on. Parasites are a major cause of disease in man, his livestock and crops, leading to poor yield and economic loss. The biocontrol of parasites therefore entails the use of BCAs to suppress the population of the parasites. This chapter focuses on the biological control of parasites, providing a brief history of bio ‐ control; their advantages and disadvantages; types of BCAs including predators, parasites (parasitoids) and pathogens (fungi, bacteria, viruses and virus‐like particles, protozoa and nematodes); their effect on the native biodiversity; a few case studies of successful implemen ‐ tation of biocontrol; challenges encountered with the implementation of biocontrol strategies and finally their future perspectives. 2. History of biological control The concept of biological control is not entirely new. The ancient Egyptians were probably the first to employ biocontrol dating some 4000 years ago, when they observed that cats fed on rodents, which damaged their crops. This most likely led to the domestication of the house cat [ 4]. However, the first record of biocontrol is from China.- eBook - PDF

- Cristina García Jaime(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Delve Publishing(Publisher)

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-biology2/chapter/steps-of-virus-infections/ Foodborne Microorganisms 153 6.4. FOOD-BORNE PARASITIC INFECTIONS Parasites are one of the major problems facing the livestock production industry in the world today. There are ecto-and endo-parasites, each playing their significant roles in affecting domestic animals as a source of food for man. With the ever-increasing world population and the subsequent decreasing amount of food per head, man can no longer afford to share his animal food resources with parasites if he has to survive. It is therefore imperative that man understands fully the epidemiology of parasites that compete against him for food in order to be able to cope with their effective control. Parasites are known to present negative nutritional effects on the host. Helminths utilize the nutrients that are intended to benefit the host. 6.4.1. Hookworms Hookworms and the etiology of iron deficiency anemia have been documented by many authors. Studies showing the relationship between hookworm infestation (and with special reference to load of worms) and severity of anemia were demonstrated as early as the 18 th century. Early and recent studies continue to support the early evidence associating hookworm and iron deficiency anemia. Studies have shown that when a patient has a load of over 1,000 hookworms, there would be blood and iron loss that is sufficient enough to upset iron balances. Even as few as 10 adult hookworms can induce a gross iron deficiency anemia (Wolf-Hall and Nganje, 2017). Hookworm is a major cause of iron deficiency anemia through blood and iron losses. There is a statistically significant correlation between circulating hemoglobin levels and hookworm load. In addition, when the hookworms are removed through deworming, there is a slow rise in hemoglobin even when the patient remains on the usual diet. - eBook - ePub

- Jamie Bojko, Alison M Dunn, April M H Blakeslee, Jamie Bojko, Alison M Dunn, April M H Blakeslee(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- CAB International(Publisher)

9 Parasite Invasions and Food SecurityLouisa E. Wood1 ,2* , Morag Clinton2 ,3, David Bass2 , Jamie Bojko4 ,5, Rachel Foster6 , James Guilder2 , Adam Kennerley2 , Ed Peeler2 , Ava Waine2 and Hannah Tidbury21 University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland; 2 Centre for Environment Fisheries and Aquaculture Science, Weymouth, UK; 3 University of Alaska Fairbanks, Alaska, USA; 4 Teesside University, Middlesbrough, UK; 5 National Horizons Centre, Teesside University, Darlington, UK; 6 Natural History Museum, London, UK© CAB International 2023. Parasites and Biological Invasions (eds J. Bojko et al.)DOI: 10.1079/9781789248135.0009 AbstractGlobal food security is of vital importance. Without it, we risk the collapse of our food chain and put important culture systems at risk of parasitism. A major risk in food security is the sudden appearance of a parasite that could decimate crops, livestock or impact human health. In this chapter we provide an overview of how invasions pose a significant risk of parasite introduction for food production systems, and how policy and management are currently poised to respond to such events. Biosecurity measures, designed to mitigate invasions, represent a vital area for further development. Socially, human communities could be at high risk of losing crops and livestock to invasive parasites, which could result in multiple knock-on effects. Protecting food security is a priority at all levels of the supply chain, from disease preventative measures on farms, to enhanced and integrated legislation/policy to prevent the spread of both invasive hosts and parasites. - eBook - PDF

Ecology

From Individuals to Ecosystems

- Michael Begon, Colin R. Townsend, John L. Harper(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

12.1 Introduction: parasites, pathogens, infection and disease Previously, in Chapter 9, we defined a parasite as an organism that obtains its nutrients from one or a very few host individuals, normally causing harm but not causing death immediately. We must follow this now with some more definitions, since there are a number of related terms that are often misused, and it is important not to do so. When parasites colonize a host, that host is said to harbor an infection. Only if that infection gives rise to symptoms that are clearly harmful to the host should the host be said to have a dis- ease. With many parasites, there is a presumption that the host can be harmed, but no specific symptoms have as yet been identified, and hence there is no disease. ‘Pathogen’ is a term that may be applied to any parasite that gives rise to a disease (i.e. is ‘pathogenic’). Thus, measles and tuberculosis are infectious diseases (combinations of symptoms resulting from infections). Measles is the result of a measles virus infection; tuberculosis is the result of a bacterial (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) infection. The measles virus and M. tuberculosis are pathogens. But measles is not a pathogen, and there is no such thing as a tuberculosis infection. Parasites are an important group of organisms in the most dir- ect sense. Millions of people are killed each year by various types of infection, and many millions more are debilitated or deformed (250 million cases of elephantiasis at present, over 200 million cases of bilharzia, and the list goes on). When the effects of parasites on domesticated animals and crops are added to this, the cost in terms of human misery and economic loss becomes immense. Of course, humans make things easy for the parasites by living in dense and aggregated populations and forcing their domesticated animals and crops to do the same. - eBook - PDF

- Jonathan Roughgarden, Robert M May, Simon A. Levin, Jonathan Roughgarden, Robert M May, Simon A. Levin, Jonathan Roughgarden, Robert May, Simon Levin(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

We conclude with a HOSTS AND PARASITES 321 "view to the future," giving a list of problems that we believe will repay further study. B A S I C I D E A S Host-Parasitoid More than 10% of all metazoan species are insect parasitoids, a term first applied by Reuter (1913) to describe insects that develop as larvae on or in the tissues of other arthropods, which they kill as a developmental necessity. The population dynamics of such associations were first explored systematically by Nicholson and Bailey (1935), using equations that can be generalized to read K + I= FNJ(N„P t ), (22.1a) P 1 + 1 = cN t [\-f(N„P t )\ (22.1b) Here N and P are the host and parasitoid populations, respectively, in successive generations, t and t + 1; F is the per capita reproductive rate of the host population (F will in general depend on the host density, F(N 1 ), but many studies treat it as a constant); and c is the average number of adult female parasitoids emerging from each parasitized host (c therefore includes the average number of eggs layed per host parasitized, the survival of these progeny, and their sex ratio). The functional response, f, defines the fraction of hosts escaping parasitism, which in general will depend on both host and parasitoid population density. Nicholson and Bailey assumed parasitoids to search independently randomly in a homogeneous environment, where/is the zerozA term in a Poisson distribution (f = exp(— aP), with Λ the "searching efficiency" of the parasitoid); such a system always exhibits oscillations of diverging amplitude. Host-Macroparasite Anderson and May (1979) have found it useful to distinguish between "micro- parasites" and "macroparasites"; this distinction is made on the basis of popula- tion biology, rather than conventional taxonomy. Broadly speaking, micropara- sites are those having direct reproduction, usually at very high rates, within the host. As exemplified by most viral and bacterial and many protozoan infections, microparasites tend to be small in size and to have short generation times. Although there are many exceptions, the duration of infection is typically short relative to the average life span of the host, and hosts that recover usually possess immunity against reinfection, often for life. Microparasitic infections are

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.