History

American Modernism

American Modernism was a cultural movement in the early 20th century that encompassed literature, art, music, and architecture. It was characterized by a break from traditional forms and a focus on experimentation, individualism, and the exploration of new ideas and techniques. American Modernist works often reflected the changing social and cultural landscape of the time, and the movement had a significant impact on shaping American identity and creativity.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "American Modernism"

- eBook - PDF

- Sean Latham, Gayle Rogers(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

1 The Emergence of “Modernism” Overview How did a collection of formally experimental writers and artists working in the early twentieth century come to be known as “modernists”? Contrary to a longstanding belief that this term was only applied retroactively, “modernism,” it turns out, is a charged, complex word that was claimed, debated, transformed, and promulgated pointedly in the early 1900s as disparate cultural trends and forces converged. Indeed, to glance at the entries in the Oxford English Dictionary for “modernism” and “modernist” is to find the familiar senses of the terms—“any of various movements in art, architecture, literature, etc., generally characterized by a deliberate break with classical and traditional forms or methods of expression,” and an “adherent or exponent” of such movements—buried amid a half-dozen other definitions from philosophical, theological, and other histories from across centuries (“modernism”; “modernist”). If anything, “modernism” risked meaning too many things in the early twentieth century. In this chapter, therefore, we will attempt to discern the ways in which it came to be associated with a particular set of arguments that become ever more pressing at the moment. Here, “modernism” emerged as the name of a nascent aesthetic idea as well a brand name that was contested fiercely by generations of creators and critics. In the space of just a few decades in the first half of the twentieth century, academics narrowed these debates into a more or less coherent tradition—to return to our metaphor, MODERNISM: EVOLUTION OF AN IDEA 18 a cable encircling a small archive of works around the term “modernism.” As we will see, even as early as 1924, the poet-critic John Crowe Ransom believed that a writer could “escape” neither from “modernism” nor from the critics who judged literature by the tenets its figures delineated (“Future” 2). - eBook - PDF

- Catherine Morley(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Edinburgh University Press(Publisher)

In the United States in particular, where the effects of mass consumerism were most obvious, this anarchic modernity was also the result of technological dynamism, scientific innovation, the rise of cosmopolitanism, the development of a self-consciously pro-gressive metropolitan culture and the emergence of phenomenol-ogy, anthropology and sociology, as well as cultural events such as the publication of Einstein’s special theory of relativity in 1905 and the translation into English of Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams (1913). The newly discovered elasticity of time and the emergence of new social sciences and philosophical discourses would rattle the foundations of individuals’ sense of self and shake the pillars of religious belief, adding to the unsettlement caused by the publica-tion of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859. But this kind of cultural anarchy was not unique to American modernity. It was deeply embedded in the socio-cultural landscape; not only were memories of the Civil War still raw (especially in the South), but throughout the nineteenth century the very borders of the nation had been constantly revised, helping to confirm a sense of flux and change. We cannot understand American modern-ism unless we grasp the importance of this historical framework: a context of upheaval, optimism and expansion, rooted in the experience of the frontier, the shock of civil war and the trauma of occupation, both physical and psychological. And while many commentators and literary critics argue that essentially American Modernism grew out of European modernism, the truth is rather different. In reality, American Modernism was firmly rooted in the nineteenth century and the antebellum writing of the American Renaissance. William Carlos Williams’s minimalist verse, for example, was clearly influenced by Emily Dickinson’s compact, elliptical poetry, while his use of American speech rhythms in his longer poems owes much to Walt Whitman. - No longer available |Learn more

Making Race

Modernism and "Racial Art" in America

- Jacqueline Francis(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- University of Washington Press(Publisher)

27 two THE MEANINGS OF MODERNISM In the early twentieth century, modernism broadly referenced a number of art styles and subjects that Americans deemed new. In 1933 New York critic Forbes Watson rightly referred to modern art styles in the plural when he discussed the “development of a series of international painting-fashions” during the first decades of the century. 1 Modernist practices were as numerous as the interpretations of them. Throughout this book, “modernism” connotes the move away from naturalism in painting and toward abstrac-tion—moderate and radical—of figure and ground. 2 Malvin Gray Johnson, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and Max Weber were variably relegated to, self-identified with, and invested in painting “the other” as new and innovative content, and in writing about them I also locate a reflexive ethnic and racial representation within modernism’s boundaries. Before discussing these artists’ modernist formal strategies, I will first engage a social aspect of modernism, namely the ways in which bodies were ideologically constructed, understood, and disci- 28 THE MEANINGS OF MODERNISM plined in its name. Modernism emerged, in part, from a transvaluation of ideas and cultures, and was perfectly tautological: it did not end unequal, historical relationships but instead maintained them and the essentialized identities of all concerned parties. In sum, the modernist framework, defined by negations, required opposition and opposites to establish its authority, meaning, and status. Race was discursively central to modernity, and “racial art” was a significant inflection of American Modernism. 3 The headline of a newspaper review of Weber’s 1923 one-artist exhibition at New York’s Montross Gallery deemed him a modernist, and, within the review, critic Henry McBride proclaimed, “Jewish-ness in art, at least of this quality, is new.” 4 Nonetheless, in the U.S. - No longer available |Learn more

Aesthetic Innovation and the Democratic Principle

Essays on Twentieth-Century American Poetry and Fiction

- Heinz Ickstadt, Susanne Rohr, Peter Schneck, Sabine Sielke(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Universitätsverlag Winter(Publisher)

2 See, e.g., the 1987 special issue “Modernist Culture in America” of American Studies (Singal); Sollors, “Ethnic Modernism”; as well as my own contributions to the dis-cussion: “Deconstructing/Reconstructing Order”; “Die amerikanische Moderne”; and, earlier, “Modernisierung und die Tradition des Neuen.” I admit that the ambi-valent status of American Modernism has held a great fascination for me throughout my academic life so that I have returned to it time and again. 3 “Indeed,” Huyssen continues, “modernism as an adversary culture (Lionel Trilling) cannot be discussed without introducing the concept of alternative modernities to which the multiple modernisms and their different trajectories remain tied in com-plex mediated ways” (191). See also Kadir and Löbbermann. 88 Imaginaries of American Modernism American Modernism, by attempting to create an art expressive of an al-ready modernizing nation, seemed more in alignment with its technological environment – even though it did encounter resistance from a restrictive and still powerful genteel cultural tradition that modelled itself on Euro-pean, especially on English ‘high’ culture. Centered mostly in New York, American Modernism integrated elements of a thriving metropolitan, popu-lar and commercial culture of modernity, at the same time that it reached back to what were considered the beginnings of a national cultural tradition originating with Emerson and Whitman. In doing so, it absorbed and modi-fied the iconoclastic innovations of various European avant-gardes, level-ing the differences between them in the process. It was thus possible to see American Modernism as part of an international movement and yet also, as Kenner phrased i t, as a distinct “homemade world” – as a box within a box which contained, as yet another box, the counter-modernism of the Harlem Renaissance and its attempt “to beat barbaric beauty out of a white frame” (McKay 94). - eBook - PDF

- Vincent Sherry(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

6 Modernism would continue after the war, and its genre- blurring, experimental creativity would continue, but the meaning of the ruptures and transformations wrought by modernization would be radically different. Avant Guerre As a concept, or as a set of related aesthetics or sensibilities, “modernism” did not spring into being in 1922, or 1914, or 1910, or any other single year. Nonetheless, the period between the publication of F.T. Marinetti’s “Mani- festo of Futurism” on the front page of Le Figaro on February 20, 1909, and Austria’s declaration of war on July 28, 1914, witnessed the public impact of modernism across Europe and the United States. This history may be witnessed most vividly in the pairing of aesthetic inventions and institutional innovations. In 1910, London experienced its first major public recognition of continen- tal modern art. Returning to London after a period as a curator of paintings at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, where he tried desperately to reform the museum’s acquisitions and exhibition strategies, 7 key Bloomsbury art critic Roger Fry took advantage of the slow winter season to launch the exhibition “Manet and the Post-Impressionists” at the Grafton Galleries. British audiences had scarcely come to appreciate the French impressionism that was already a half century old when Fry offered them The 1910s and the Great War 103 “post-impressionist” art – a term he coined for the work of artists such as Cézanne, van Gogh, and Gauguin (who had all died years before the exhib- ition opened) and a younger generation that included Picasso, Matisse, and Signac, among others. Most importantly, Fry conveyed a sense of modern art as a coherent movement with an appreciable aesthetic capable of engaging contemporaneity. While most critics were openly hostile, using terms such as “pornography” and “sickness of the soul” to describe the art, the exhibition ran until January 1911. - eBook - PDF

Gardner's Art through the Ages

A Concise Global History

- Fred Kleiner(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

However, in the decades following that new global conflict, American painters, sculptors, and architects often took the lead in establishing innovative styles that artists elsewhere quickly emulated. This new preeminence of the United States in the arts is the subject of Chapter 15. Explore the era further in MindTap with videos of major artworks and buildings, Google Earth ™ coordinates, and essays by the author on the following additional subjects: • André Derain, The Dance ( fig. 14-3A ) ❚ ART AND SOCIETY: Science and Art in the Early 20th Century ❚ ART AND SOCIETY: Primitivism and Colonialism • Arthur Dove, Nature Symbolized No. 2 ( fig. 14-17A ) ❚ ART AND SOCIETY: Art “Matronage” in the United States • Henry Moore, Reclining Figure ( fig. 14-30A ) • José Clemente Orozco, Epic of American Civilization: Hispano-America ( fig. 14-37A ) • William van Alen, Chrysler Building, New York ( fig. 14-41A ) 14-43 Frank Lloyd Wright, Kaufmann House (Fallingwater; looking northeast), Bear Run, Pennsylvania, 1936–1939. Perched on a rocky hillside over a waterfall, Wright’s Falling- water has long, sweeping lines, unconfined by abrupt wall limits, that reach out and cap-ture the expansiveness of the natural environment. Copyright 2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. MODERNISM IN EUROPE AND AMERICA, 1900 TO 1945 Dalí, The Persistence of Memory, 1931 Gropius, Bauhaus, Dessau, 1925–1926 THE BIG PICTURE Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913 Douglas, Noah’s Ark, ca. - eBook - PDF

Gardner's Art through the Ages

A Concise Western History

- Fred Kleiner(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

However, in the decades following that new global conflict, American painters, sculptors, and architects often took the lead in establishing innovative styles that artists elsewhere quickly emulated. This new preeminence of the United States in the arts is the subject of Chapter 15. Explore the era further in MindTap with videos of major artworks and buildings, Google Earth™ coordinates, and essays by the author on the following additional subjects: • André Derain, The Dance (fig. 14-3A) ❚ ART AND SOCIETY: Science and Art in the Early 20th Century ❚ ART AND SOCIETY: Primitivism and Colonialism • Arthur Dove, Nature Symbolized No. 2 (fig. 14-17A) ❚ ART AND SOCIETY: Art “Matronage” in the United States • Henry Moore, Reclining Figure (fig. 14-30A) • José Clemente Orozco, Epic of American Civilization: Hispano-America (fig. 14-37A) • William van Alen, Chrysler Building, New York (fig. 14-41A) 14-43 Frank Lloyd Wright, Kaufmann House (Fallingwater; looking northeast), Bear Run, Pennsylvania, 1936–1939. Perched on a rocky hillside over a waterfall, Wright’s Falling- water has long, sweeping lines, unconfined by abrupt wall limits, that reach out and cap- ture the expansiveness of the natural environment. Copyright 2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. MODERNISM IN EUROPE AND AMERICA, 1900 TO 1945 Dalí, The Persistence of Memory, 1931 Gropius, Bauhaus, Dessau, 1925–1926 THE BIG PICTURE Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913 Douglas, Noah’s Ark, ca. - eBook - PDF

The Turn of the Century/Le tournant du siècle

Modernism and Modernity in Literature and the Arts/Le modernisme et la modernité dans la littérature et les arts

- Christian Berg, Frank Durieux, Geert Lernout(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

52 Poggioli: The Theory of the Avant-Garde, p. 5. 53 Ibid., p. 5. 54 For a discussion of this quotation, see Weisstein: Vorticism: Expressionism English Style. 55 The artistic upshot of that acquaintance was her novel To the Lighthouse. 422 Interdisciplinary Approaches book Modern Poetry and the Tradition in 1939 provided the term with its schol-arly legitimation as well. 'Modernism' proper, still taken in its broadest possible sense ('the methods, style or attitude of modern artists; especially the style of painting in which the artist deliberately breaks away from classical and traditional methods of expression — hence a similar style or movement in architecture, literature, music, etc.) 56 and regarded as an outright Germanism, 57 entered the art-historical discourse as early as 1934 but did not attain literary currency un-til the sixties, following publication of Harry Levin's inconclusive and now sadly dated lecture What Was Modernism? 58 That piece was followed, in due course, by Literary Modernism , a collection of essays edited by Irving Howe (1967) 59 and by Joseph Chiari's book The Esthetics of Modernism (1970). It had been preceded by 'modernist,' a term, used as early as 1927, in its ad-jectival and nounal guise. It was in that year that Laura Riding and Robert Graves published their Survey of Modernist Poetry, which, as Calinescu shows in some detail, 60 turns out to be more or less irrelevant to our topic, and that in his History of Modern Painting, the art historian Frank J. Mather spoke of the Modernists as hav(ing) attained nothing of the coherence or authority of a school. 61 That much for 'Modernism' in the wider, more colloquial sense. Given this extremely loose definition, however, it can hardly be regarded as consti-tuting a viable period term. - eBook - PDF

- Rachel Potter(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Edinburgh University Press(Publisher)

chapter 4 Modernism and Mass culture I n the introduction to this book I described some of the specific features of the new mass media of the early twentieth century: an expanding mass-distribution newspaper network and reader- ship, cheap mass-produced novels, the cinema and the radio. While modernist writers had complicated relationships to each of these things, they also engaged with the literary impact of mass culture, a term that synthesises these different cultural forms and implies that a capitalist logic of commercial exploitation holds them together. The term, and what it implies, has served a dual purpose. Claims about modernism as a collective artistic endeav- our have often been grounded in arguments about its separation from mass cultural entertainment. But this argument has proved controversial in responses both to modernist writing, and its self- definitions. Where does the difference reside? Who decides that one kind of novel is written and consumed for entertainment, and another kind of novel explores truth and beauty and forms part of a privileged literary tradition? For many readers and critics, the very idea of art as something distinct from mass or popular culture involves a problematic distaste for popular writing. The Marxist cultural critic Antonio Gramsci argued that it relies on the imposition of the values of a dominant and privileged class and denigrates the expressive resistance of subordinate groups. Theodor Adorno, in contrast, while also working within a Marxist tradition, claimed that modernist art, in its difficulty and disso- modernism and mass culture 147 nance, resists the absolute capitalist domination of the cultural sphere. Adorno wrote about a wide range of subjects in his lifetime, including philosophy, musicology, social theory, literature and art. One of his boldest arguments was that radio, cinema and leisure time had become forms of ‘administered life’. - eBook - PDF

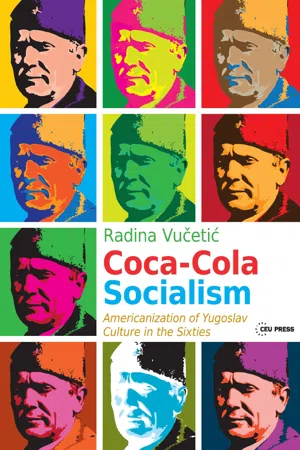

Coca-Cola Socialism

Americanization of Yugoslav Culture in the Sixties

- Radina Vu?eti?, Radina Vu?eti?, Radina Vučetić, John K. Cox(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Central European University Press(Publisher)

C HAPTER 3 Modernism and the Avant-Garde in the Struggle for Socialism I n the Americanization of Yugoslav culture, popular culture was— because it was directed at broad sections of the population and target groups desirable for their political influence—in the center of such process in quantitative terms, but Americanization did not avoid the spheres of high culture. The term “high culture” is difficult to define, since the twentieth century was a time when the differences between these two cultural streams were frequently erased. An additional exac-erbating factor in defining high culture is that high art, like popular art, rarely manifests itself “in abstract purity,” and so individual forms of art, like jazz, film, or pop art, cannot be put into just one suitable category. 1 What makes defining American high culture even more difficult is the fact that Europe usually looked down on it with disdain and con-sidered it a copy of European culture, not realizing that since World War II the Paris art scene had decamped for New York, as well as that American institutions, such as the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Guggenheim Foundation, began to work on the Americaniza-tion of European culture, which contributes to the great changes in the conceptualization of art in the second half of the twentieth century. 2 1 Hauser, Sociologija umetnosti , 2, 97–100. 2 Wagnleitner, Coca-Colonization and the Cold War , 166–167; Stephan, “A Special German Case of Cultural Americanization,” in The Americanization of Europe , 75–78. 138 COCA-COLA SOCIALISM In the wish to see American culture affirmed at the global level, the State Department saw one of its goals in the task of showing the world that American reality was formed not just by Disney, Holly-wood, and chewing gum, but also by high culture.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.