History

Apache tribe

The Apache tribe is a Native American group known for their fierce resistance against European colonization in the southwestern United States. They were skilled warriors and hunters, and their nomadic lifestyle allowed them to adapt to various environments. The Apache people have a rich cultural heritage, with traditional practices and beliefs that continue to be celebrated today.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

6 Key excerpts on "Apache tribe"

- eBook - PDF

- Veronica E. Verlade Tiller(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

1 Introduction to the Apache tribes WHO ARE THE APACHES? The historical identification of the Apache people—who they are, where they came from, and how they got to where they are—is at best complex, perplexing, and difficult, even for people who consider themselves Apache scholars. There are several reasons for this mosaic of complexity. Since the first contact between the Apaches and the Spanish in the Southwest in the six- teenth century, the Spanish chroniclers, missionaries, the military, and government officials could not keep track of the Apaches, much less identify them by name. As nomadic peoples they moved from place to place over their huge territories. When the Spanish thought they had identified an Apache band with a particular physical location, like a mountain or river, and assigned them a name, the following year either the band moved on or another band took their place. Apaches were indeed true nomads. The Span- ish accounts are replete with names for Apache bands that did not survive over time. The Americans inherited this situation as they encountered the Apache people beginning in the early 1800s. It was not until the Apache Wars and when they were settled onto reservations that the Apache people were finally identified by tribal groups and affiliations. As the U.S. military forces fought the Apaches, they began to recognize bands and their leading warriors as belonging to a larger tribe or a particular location, like the Chiricahua who inhabited southwestern New Mexico and southeastern Arizona. During the Indian wars, some of the smaller Apache bands were consolidated with either larger bands or groups of bands from a certain area. For example, the White Mountain Apaches of east-central Arizona consist of historic Apache bands such as the Coyoteros, Arivaipas, Cibecue, and Mogollons. 1 The San Carlos Indian Reservation of southeastern Arizona has Apache bands that were historically known as Gila Apaches, Mimbren ˜os, and others. - eBook - ePub

To Live and Die in the West

The American Indian Wars

- Jason Hook, Martin Pegler(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The Apaches IntroductionThe origin of the name ‘Apache’ is unclear, though it probably stems from the Zuni ‘ápachu’, their name for the Navajo, who the early Spaniards called ‘Apaches de Nabaju’. One suggested alternative is that it originated in the rare Spanish spelling ‘apache’ of ‘mapache’, meaning raccoon, which in view of the distinctive white stripes typically daubed across a warrior’s face is rather attractive, if unlikely. The Apaches in fact referred to themselves with variants of ‘ndé’, simply meaning, in common with many Indian self-designations, ‘the people’.The Apache culture of 1850 was a blend of influences from the peoples of the Great Plains, Great Basin and the South-West, particularly the Pueblos, and—as time progressed—from the Spanish and American settlers. Tribal peculiarities depended upon geographical location in relation to these peoples, and the time and route of a tribe’s early migration. In a work of this size, generalisations concerning ‘typical’ Apache traits of the Chiricahua, Mescalero, Jicarilla, Western and Lipan Apaches—e.g. the eating of mescal, hunting and gathering economy, the puberty rite, masked impersonators of the Mountain Spirit supernaturals—inevitably have to be made. Tribal and indeed individual divergences naturally occurred in what was a highly individualistic society; but where a reference is made to a common trait, it describes a feature considered integral to the rich and distinctive Apachean culture.An 1880s studio shot of Nalté, a San Carlos Apache warrior, labelled the ‘San Carlos dude’. Note the identification tag hanging from his necklace, and the quirt on a thong around his wrist. The Frank Wesson carbine he is holding is a studio prop. (Arizona State Museum, University of Arizona)The Apache tribesThe Apachean or Southern Athapaskan language, and therefore the Apache people themselves, can be divided into seven tribal groups: Navajo, Western, Chiricahua, Mescalero, Jicarilla, Lipan, and Kiowa-Apache. For the purposes of this work, the Navajo - eBook - PDF

Native Americans

An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Peoples [2 volumes]

- Barry M. Pritzker(Author)

- 1998(Publication Date)

- ABC-CLIO(Publisher)

Detailed and extensive knowledge was needed to perform ceremonials; chants were many, long, and very complicated. Power could also be evil as well as good and was to be treated with respect. Witchcraft, as well as incest, was an unpardonable offense. Finally, Apaches believed that since other living things were once people, we are merely following in the footsteps of those who have gone before. Government Each of the Western Apache tribes was considered autonomous and distinct, although intermarriage did occur. Tribal cohesion was minimal; there was no central political authority. A “tribe” was based on a common territory, language, and culture. Each was made up of between two and five bands of greatly varying size. Bands formed the most important Apache unit, which were in turn composed of local groups (35–200 people in extended families, themselves led by a headman) headed by a chief. The chief lectured his followers before sunrise every morning on proper behavior. His authority was based on his personal qualities and perhaps his ceremonial knowledge. Decisions were taken by consensus. One of the chief’s most important functions was to mitigate friction among his people. Customs Women were the anchors of the Apache family. Residence was matrilocal. Besides the political organization, society was divided into a number of matrilineal clans, which further tied families together. Apaches in general respected the elderly and valued honesty above most other qualities. Gender roles were clearly defined but not rigidly enforced. Women gathered, prepared, and stored food; built the home; carried water; gathered fuel; cared for the children; tanned, dyed, and decorated hides; and wove baskets. Men hunted, raided, and waged war. They also made weapons, were responsible for their horses and equipment, and made musical instruments. - eBook - PDF

- Matthew Babcock(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Some of the most respected English, Spanish, and French language dictionaries are also part of the problem. They continue to offer antiquated definitions for the word Apache, such as “bandit,” “highway robber,” and “ruffian or thug,” which derive from the ethnocentric observations of nineteenth-century European observers. 13 The portrayal of Apaches as relentless warriors is at best superficial. It fails to address cultural change over time and varieties among tribal groups. Specialists understand, of course, that Apaches have a long history of contact with Euro-Americans, which dates back at least to Francisco Coronado’s expedition in 1540. 14 Few historians of the nineteenth- century American West, however, are aware that thousands of Apaches, including the relatives of well-known future leaders such as Juan José Compá, Mangas Coloradas, and Cochise, settled on Spanish-run reserva- tions fifty years prior to the U.S.–Mexican War. Frequently these same scholars mistakenly assume that the Spanish and Mexican military only minimally impacted Apache culture, their soldiers “could do next to nothing to control the Apaches,” and Apaches’ first significant contact with outsiders began when Anglo Americans entered the region in signifi- cant numbers during the 1840s. 15 Mexican scholars, on the other hand, are much better versed in Apache history prior to 1846. They, too, however, regard Apaches as indios bárbaros, or savages, owing to the Introduction 7 escalation of Apache raiding in northern Mexico during the 1830s. 16 Even most regional specialists concur that Apaches never made lasting peace agreements with Spaniards. These historians view the mission, not the presidio, as the primary institution for “civilizing” Apaches in the region and ignore the presidio’s role as a reservation agency. 17 Challenging these assumptions, this book offers a new interpretation of Apache–Hispanic relations that examines both cultures from multiple perspectives in a global context. - Available until 7 Feb |Learn more

Apache Reservation

Indigenous Peoples & the American State

- Richard J. Perry(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- University of Texas Press(Publisher)

More often, though, many Apache leaders became convinced that the only hope for the physical survival of their people was peaceful submission to reservation life. For years many of them had witnessed the slaughter of their children and relatives. They had seen their numbers depleted and had lost control of their territorial base. Some, such as the Arivaipa leader Eskiminzin and the Chiricahua Loco, decided that to continue resistance would mean the complete destruction of their people. Helping the army to locate the few bands who remained off the reservation was, to them, a matter of helping their people go on living.But the tales of fighting, slaughter, and destruction are manifestations of other processes that acted to shape events. From one perspective we might be tempted to view the process as an inevitable outcome of Apache raiding. When the Apache began depending on the production of other groups, they placed themselves in conflict with the interests of these peoples. This brought about increasing assaults on their own population. One might argue that if the Apache had stuck to hunting, gathering, and gardening within their own territory this might have been avoided.But such a scenario has its flaws. We have only to look at the scores of peaceful, stable Native American populations elsewhere whose territories were overrun long before the Apache lost theirs. Many of those peoples were all but eliminated. The Apache, on the other hand, managed to hold off the concerted assaults of three different states for centuries before they finally succumbed.In 1871 the Arizona Territorial Legislature complained that Apache depredations constituted an obstacle to “immigration and capital” necessary to develop the region. They went on to assert:Probably, but few countries on the face of the globe presents greater natural resources inviting to immigration and capital than the Territory of Arizona. Nearly every mountain is threaded with veins of gold, silver, copper, and lead. Large deposits of coal and salt of an excellent quality are found. Nearly every foot of the Territory is covered with nutritious grasses, and stock thrives the year round without shelter or prepared forage. Nearly every product that grows in the temperate or torrid zone can be grown here to perfection and in abundance. There are vast forests of excellent timber; the mountains and valleys are amply supplied with pure water; the climate is warm, genial, and healthful, equal to any on the American continent. (Arizona Territorial Legislature 1871:3) - eBook - PDF

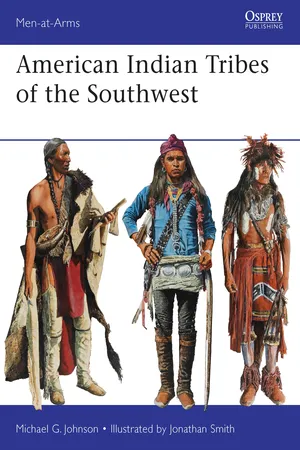

- Michael G Johnson, Jonathan Smith(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Osprey Publishing(Publisher)

10 in 1821 this policy lapsed due to the new government’s lack of funds, and the Apaches resumed intensive raiding into Sonora. The capture for adoption of Mexican women and children altered their genetic composition, though their language, mythology, ritual and social organization remained largely unaltered. (The exception were the Lipan people, who had extensive contact with the Spanish in Texas.) The presence of the Apacheans in the Southwest is considered relatively recent by many investigators, who believe that the Querechos (1541), Teyas, Vasqueros (1630) and Mansos reported by Spanish explorers on the Southern Plains or in northern Mexico were Apaches. An archaeological site at Dismal River, Nebraska, from c. 1675 has been attributed to the Plains Apache. The Western Apache, whose historic territory lay south of the Navajo, may well have preceded them into their subsequent locations in New Mexico and Arizona. In 1981 the numbers of Apache still speaking their native languages were given as: Western Apache, 12,000; Mescalero-Chiricahua, 1,700; Jicarilla, 800; Kiowa Apache, 20; and Lipan, just 3. Western or San Carlos Apache (Coyotero) During the period 1848–53 when Arizona and New Mexico became part of the US, the Western Apache consisted of five major sub-tribes, each again divided into small bands, all located within presentday Arizona. The five sub-tribes and their constituent bands were: (1) San Carlos proper. Four bands: Apache Peaks band in Apache Mtns northwest of Globe; Arivaipa band on Arivaipa Creek; Pinal band between the Salt and Gila rivers; San Carlos band around the San Carlos River. (2) White Mountain. Two bands: Eastern White Mountain band in the region of the Upper Gila and Salt rivers; Western White Mountain band between the Eastern White Mountain and San Carlos bands. (3) Cibecue. Three bands: Canyon Creek band on Canyon Creek; Carrizo band on Carrizo Creek in Gila County; Cibecue band on Cibecue Creek.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.